Chinese Sculpture

CHINESE SCULPTURE. The historical records about sculptural works in China do not begin until the Ch'in dynasty (221-206 B.C.) ; the earliest refer to the 12 colossal statues of "the giant barbarians" and the bell-frames in the shape of monsters "with stags' heads and dragons' bodies," which the great emperor Ch'in Shih Huang Ti ordered to be cast from the weapons of war collected throughout the kingdom. These enormous bronze statues which were placed before one of the imperial palaces near Hsien Yang, on the Wei river in Shensi, are mentioned by Lu Chia, an author who lived from the Ch'in to the Han dynasty, and by several later chroniclers such as Chang Heng (d. A.D. 139) who speaks of "the metal barbarians sitting in a row." At the end of the later Han dynasty Tung Chow melted "ten bronze men into small cash, also the bell-frames"; the two remaining ones he set up inside the Ch'ing Ming gate at Ch'angan but these were also lost during the 4th century, when a local ruler tried to remove them but found them too heavy for the muddy roads, the result being that one was melted down into cash, the other thrown into the river. Nothing, however, is known about the artistic character of these statues, but their well recorded history proves that they were considered extraordinary both for their motives and their size.

Ch'in Dynasty.

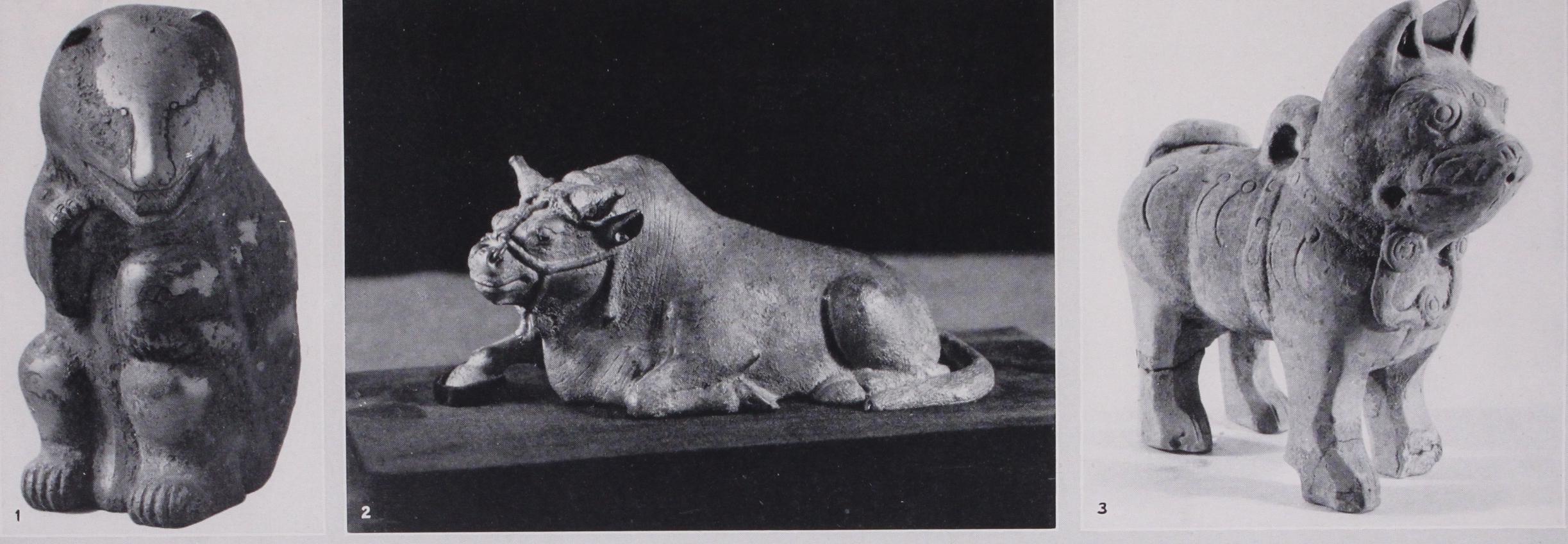

The only sculptures now remaining which possibly might be attributed to the Ch'in dynasty are some decora tive animals in bronze. Most of these are of small size and placed on the lids of sacrificial vessels, but nevertheless with a well developed sculptural character. A larger example,— sometimes ascribed to the Ch'in period—is a statuette, that represents a reclining bull (now in the possession of L. Wannieck, Paris). It is said to have been found together with some bronze vessels, decorated in Ch'in style, at Li Yu in northern Shansi, but to judge by its style, it can hardly have been executed before the 6th century A.D. (Northern Wei dynasty). We illustrate it, however, as a particularly fine example of early Chinese animal sculpture.Among other bronze animals which have been ascribed to the Ch'in period should be mentioned a large dragon or hydra with crested neck and flame-like wings at the shoulders and the loins, in the collection of A. Stoclet, Brussels. It is in marked contrast to the bull, fierce, fantastic, grotesque to the utmost without any connections with nature, and must, indeed, be earlier in date, though hardly of the Ch'in period. Other fantastic animals such as interwinding dragons or felines appear at the handles of some large bells in Ch'in style.

New efforts were evidently made in different directions during this short period which, in the field of art, was simply an intro duction to the classic age of the Hans. The rigid ceremonial art of earlier times is gradually modified by a more direct and vivid interest in nature. The Chou art (1122-256 B.C.) was pre eminently symbolic and geometrical. The art of the Ch'in and the Han periods aimed at the presentation of the actual rhythm of things, the inherent life and significance of the artistic forms.

The Han Dynasty.

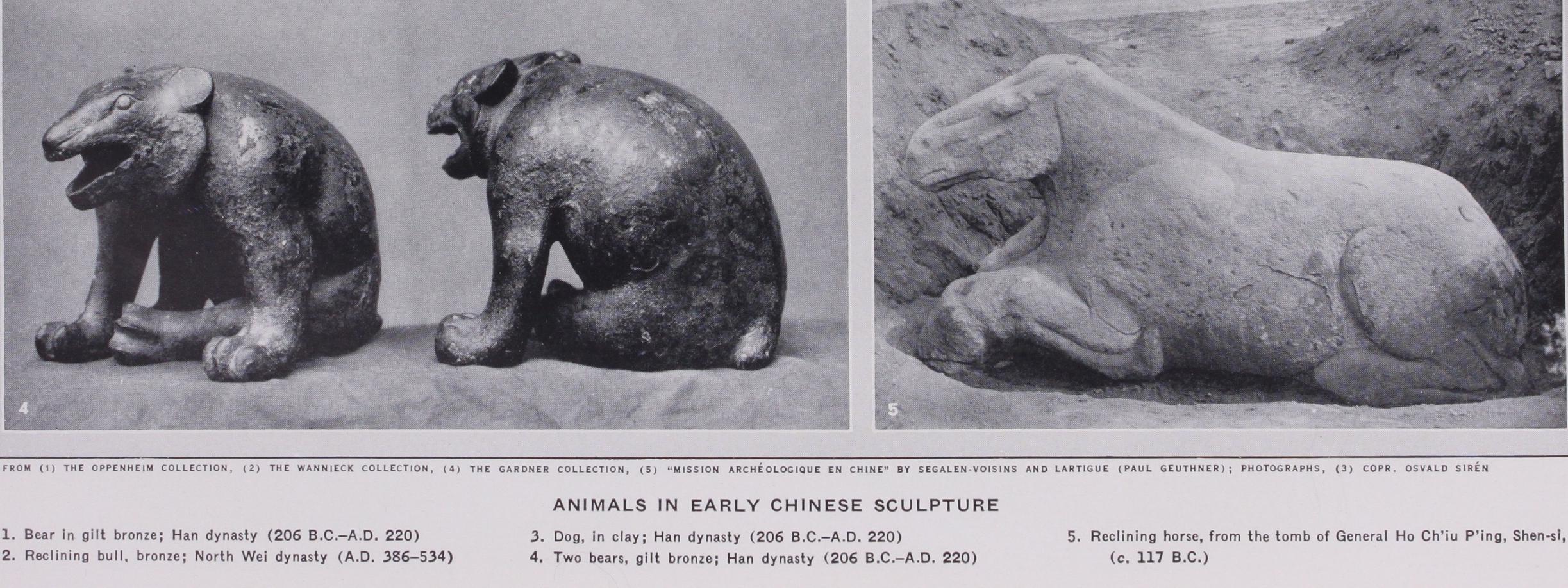

Most of the Han monuments have evidently been destroyed ; yet, to judge from those which remain as well as from minor plastic creations in bronze and clay, Chinese sculpture was at this early period much better fitted to treat animal motives than human shapes. It is only in the reliefs that the human figures reach an importance comparable to that of the animals, and these are, on the whole, more like paintings trans lated into stone than real sculptures. With the exception of the small tomb statuettes made as substitutes for real people, human representations are quite rare and artistically much inferior to the representations of animals. The Chinese have never con . sidered the human figure an artistic motive in itself, but simply used it for expressing an action or a state of consciousness. They have taken greater interest in types, postures and motives of drapery than in the bodily form or the muscular organism. The case is quite different with the animal sculptures. They may ad here to certain types or formulae characteristic of the period to which they belong but their artistic importance depends mainly on the rendering of their organic form and vitality. The best among them are monumental creations, hardly inferior to animal sculptures of any other period or nation. The conventionalization, which is more or less preponderant during the early epochs, does not convey an element of immaterial abstraction but serves to accentuate the muscular organism, the energy of movement, the monumentality of the form, all that makes the animals great and convincing as works of art.

Bronze, Clay and Stone Work of the Han.

Among the great number of wild and domestic animals represented in bronze, clay and stone during the Han period we may choose as examples some bears executed in bronze. The majority of these bears are quite small, intended to serve as feet for sacrificial vessels, but there are also some of a larger size which have the character of free standing sculptures. The two best are in the Gardner museum in Boston. These are represented in a squatting posture, stretching their heads forward with a friendly roar. The modelling of the limbs is not carried very far, yet it is sufficient to awake an impression of suppleness and force. The artist has not been afraid of exaggerations in the characterization of the lumpy forms or the telling postures. The heavy weight of the body supported by the broadly placed forepaws, the elastic power of the enormous legs, the softness of the bulky paws and the long nose which seems to form a direct continuation of the ears, are rendered with a power of conviction and a sense of monumental unity that are rarely found in later animal sculptures.It should also be noticed that in their representations of animals the Chinese have quite often combined two or more into a group. They have composed them in the most intricate positions and built up groups which satisfy the highest requirements of plastic art. Most of these groups are on a relatively small scale, but they are nevertheless truly monumental. The finest results are achieved in groups of fighting animals, because the bodies are here represented in their highest tension, in the full development of their muscular effort, and so closely interlaced that they com plete each other perfectly in the expression of the plastic idea. The same is also true of some of the animals which are composed into an architectural unity with monuments such as the tomb pillars in Szechuan (which will be mentioned below).

Tomb Statuettes of the Han.

The greatest variety of animal types may however be found among the clay statuettes made for the tombs. The material was most easily handled and thus invited all sorts of individual variations, and as these clay sculptures were executed as substitutes for living animals, which in earlier times followed their dead masters into their tombs, it was natural that they should be made as lifelike as possible. The majority are domestic animals such as horses, sheep, dogs, pigs, hens and ducks in various sizes, the smallest hardly more than two or three inches high, the largest measuring a foot or more. They were usually executed in clay moulds but sometimes modelled by hand, and the best among them have retained a spontaneous freshness and vivacity which make them very entertaining. Proportions and shapes are treated with a great deal of freedom. The dogs have enormous heads, the horses have necks which curve like high arches, and the pigs have snouts like bowsprits, yet the exaggerations serve simply to accentuate the typical features of the various animals.Besides the animals there are human ming ch'i, or tomb statu ettes, made as substitutes for living people, such as servants, and wives who formerly were buried alive with the husbands. Most common amongst these statuettes from the Han period are the slender ladies in long robes with wide sleeves reminding one of the Japanese kimonos. They stand usually in very quiet postures simply with a slight inclination of the large round head, but occasionally we find them represented in a dancing movement, though with closed feet, swinging their bodies and their arms in a rhythmic fashion.

Stone Sculptures of the Han.

Stone sculptures on a large scale were, no doubt, also executed in steadily increasing numbers during the Han period, though comparatively few of them have been preserved. Among the earliest which can be approximately dated are the animals at the tomb of General Ho Ch'ii Ping, situated at the Wei river some 20 m. N.W. of Sianfu. They were discoverd by Segalen and Lartigue during their explorations in 1914 and more completely dug out by the latter in 1923. Lartigue has also published them in an article in the German magazine Artibus Asiae (192 7) in which he presents some evi dence for the supposition that these statues were executed about "7 B.C., the year of the death of the famous general. He thinks that the statues, which represent a horse standing over a fallen warrior, a reclining horse and a buffalo, were placed in front of the mound, and that their present quite irregular positions have been caused by the shifting of the mud. Besides these, complete sculptures may, however, be seen in the neighbourhood of the mound, a large block with a mythological figure, executed in relief, and fragments of some animal sculptures which seem to indicate that this large composition never was completely finished. It is difficult to appreciate the artistic importance of these large statues without seeing the originals, but if we may draw some conclusions from the reproductions, the sculptures are compara tively undeveloped from an artistic point of view. This is par ticularly true of the main statue, the horse standing over a fallen warrior. The composition is indeed significant but the formal treatment does not seem to do justice to the motive. The short legged horse with an enormous head is more bulky than monu mental, and the figure under its belly is simply a large block. Here is little of that intrinsic energy which is so prominent in some of the minor sculptures already mentioned. This impression is, however, to some extent counteracted by the reclining horse and the buffalo which, even if they are heavy and bulky with stumpy legs, reveal a very sensitive artistic treatment, particularly in their expressive heads. Here one may discover a touch of that excellent animal psychology which is one of the greatest assets of Han art, a characterization which, to some extent, makes up for the shortcomings in other directions.

Sculpture Developed For the Dead.

Other stone sculptures from the beginning of the Han dynasty which might serve for comparison have not come to light, though it is more than probable that they have existed, because this tomb was hardly an isolated case, and broadly speak ing sculpture in stone as well as in clay had its origin in the decoration and the ar rangement of the tombs. It was for the dead rather than for the living that the Chinese developed their creative activity in the field of the plastic arts. As proof of this may be quoted not only the various classes of clay and stone sculptures men tioned above, but also numerous reliefs ex ecuted for the decoration of the "spirit chambers" of the tombs and the sculptural pillars placed in front of the mounds. These monuments marked as a rule the be ginning of the "shen tao" (spirit path) which led up to the tomb and which in later times was farther and farther ex. tended in a straight line from the mound towards the south. The interior of the tomb consisted often of two or more chambers (as also may be observed in con temporary Korean tombs), the first being a kind of ante-room called the "spirit chamber," where the soul of the deceased was supposed to dwell, while the coffin was placed, together with various vessels and other paraphernalia of bronze or clay, in the back room. The main decoration, be it in sculpture or painting, was concentrated in the ante-room where the walls often were covered with representations from ancient history and mythology or with illustrations with a moral import.

Tomb Pillars.

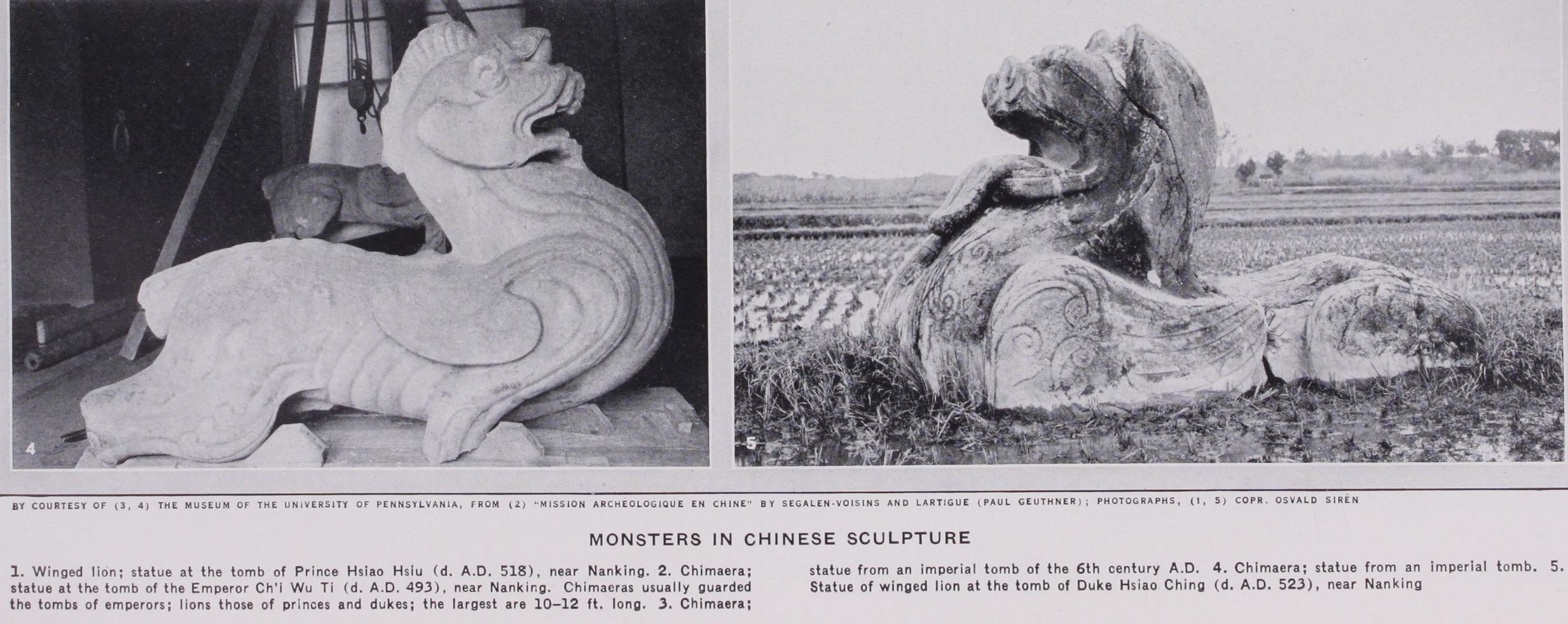

Quite a number of the decorative pillars which formed the gateway to the "spirit road" are known from central and western China, particularly the provinces of Honan, Shantung and Szechuan. They are usually constructed on a rectangular plan of large and well-fitted stone blocks reaching a total height of 5 to 18 feet. When completely preserved they consist of a moulded pedestal, a very broad shaft and a cornice over which the roof projects quite far. But the form varies somewhat in the different provinces; thus the pillars in Honan, of which the best known stand at Teng Fung Hsien on Sung Shan, are very broad and provided with projecting buttresses. Otherwise they are quite simple without any particular development of the cornices and decorated with ornaments and figures in very low relief. The earliest of these Honan pillars is dated A.D. 118, the latest A.D. The pillars in Szechuan have usually no buttresses, but they are higher and characterized by a richer architectural composition; their upper parts, the cornices and friezes under the projecting roof are particularly well developed. We find here, reproduced in stone, the beam ends and brackets so characteristic of Chinese wooden architecture, and between these are sculptural decorations executed in high relief, sometimes almost in the round. These pillars are all from the later Han dynasty, but only one of them, the pillar of Fung Huan at Ch'iu Hsien, is dated by an inscrip tion which contains the year A.D. 121.

Symbolic Decorations of the

Han.—More important for their sculptural decorations are, however, two pillars in the same neighbourhood erected at the tomb of a man called Shen. On their shafts are representations of the symbols of the four direc tions ; i.e., the red bird of the South, the white tiger of the East, the blue dragon of the West and the black tortoise of the North, animal representations which, with regard to energetic rhythm of line and grand decorative stylization, may be compared to the best works in bronze or clay known from this classic epoch. At the corners of the entablature are seated human figures which seem to carry the projecting beams on their shoulders, and, on the middle of the south side, a kind of t'ao t'ie (glutton) appears between the beams. All these figures are executed practically in the round and most skilfully composed into the architectural scheme of the monument. The very high frieze is divided into two sections, of which the lower one is decorated with hunting scenes in quite low relief and the upper one with some larger figures in high relief. One may observe here men riding on stags, horse like animals running along with the swiftness of the wind, and hunters who aim with their bows above their heads or grasp the passing leopard by its tail. Here is the same free-play with animal and human forms as may be observed on some of the inlaid bronze vessels or on the glazed Han urns with relief friezes. The motives seem to have some reference to the life beyond the tomb, though they represent this with a naturalness and an in tensity of movement which make them appear like scenes from real life. The style reveals something of the same energy and nervous tension that characterizes the small bronze ornaments of this period, and it can hardly be explained without accepting an influence from west Asiatic sources, though the Chinese transfor mation of the west Asiatic tradition is more complete in the large stone sculptures than in most of the minor bronze orna ments.

Dramatic Expression of the Pillars.

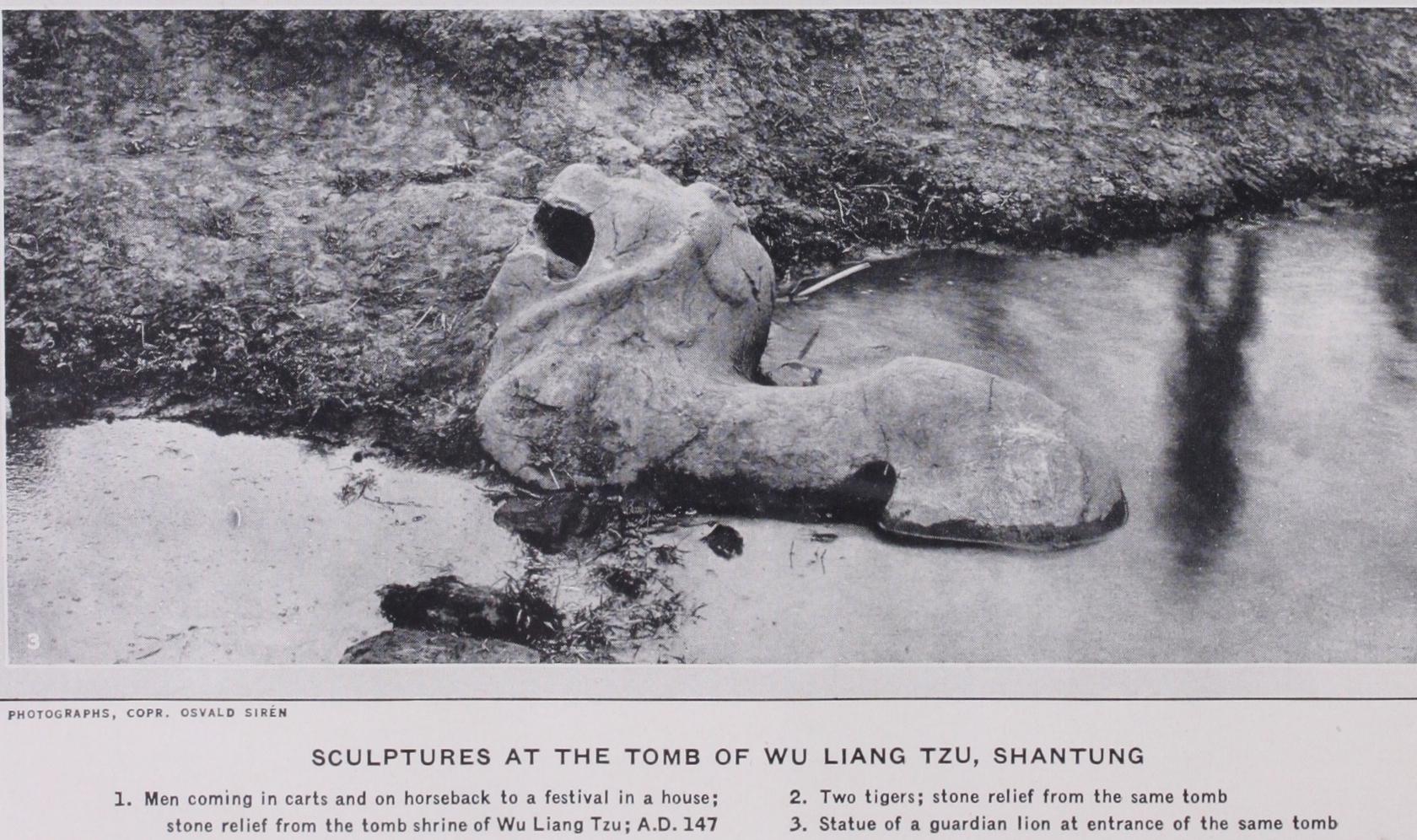

The majority of the tomb pillars in Szechuan, of which at least a score were dis covered by Segalen and Lartigue during their exploration in 1914, show the above mentioned combination of friezes with flat reliefs and tridimensional representations of animals and human figures on the entablature. The motives vary, some being histori cal or legendary, others religious or mythological, but they are all more or less imbued with a dramatic expression, and executed in a form of high decorative beauty.Much simpler than these are the pillars which stood at the entrance to the tomb of the Wu family at Ch'ia Hsiang in Shan tung. They were erected about the year A.D. 147 and they are still in their original place, although the tomb-area has become a large pit, usually filled with water. The pillars are provided with buttresses and a small superior storey on the projecting roof, but their sculptural decoration consists simply of quite low reliefs representing dragons, tigers and birds, in decorative trans lation, besides legendary illustrations with a moral import, framed by geometrical ornaments of the same kind as may be found for instance on the mirrors of the Han period.

Reliefs of the Han.

The same kind of motive, executed in a strictly conventionalized linear style, appears also on the large stone slabs which used to be arranged along the walls of the ante-chamber in the tomb, but which are now transferred to a primitive little store-room where they stand without any kind of order. These reliefs from the Wu Liang Tzu tomb have become known all over the world through numerous series of rubbings taken of them since the i8th century, and reproduced in many Chinese and European publications. Two or three of the reliefs have found their way into Western collections, though it should be noticed that the majority of the stone reliefs, said to come from Wu Liang Tzu, are simply modern imitations, made on the basis of rubbings.

Legendary Motives.

Nothing is more entertaining than to follow, with the aid of Chavannes interpretations, the legendary motives represented in these reliefs and thus to learn something about classical Chinese examples of filial piety, matrimonial fidelity, the faithfulness of loyal citizens, the valour of great heroes, not to mention the quasi-historical traditions about the great Yu and Ch'in Shih Huang Ti or the mythological stories about the king of the East, Tung Wang Kung, and the queen of of the West, Hsi Wang Mu. Very common motives in these reliefs are the long processions of riders and carriages and the rows of men on horseback escorting a carriage, which may be representa tions of the journey of the deceased to Hades.The compositions are arranged in horizontal storeys, with single rows of figures, animals, trees, houses and the like, appearing as silhouettes against a neutral background. The artistic expres sion lies mainly in the contours, and in the engraved lines ; the modelling of the forms is very slight. These reliefs may thus hardly be called sculpture in the real sense of the word, but rather paintings or drawings translated into stone. We have reason to suppose that they were made after such patterns and reproduce popular wall paintings which existed in some contemporary palaces, a supposition which is supported by the poet Wang Yen Shou, who describes the wall paintings in the Ling Kuang palace executed about the middle of the end century A.D. He mentions in his description mythological illustrations of the same kind as may be seen in the Wu Liang Tzu reliefs besides "many riotous damsels and turbulent lords, loyal knights, dutiful sons, mighty scholars, faithful wives, victors and vanquished, wise men and fools," motives which correspond more or less to those appearing on the stone reliefs from Wu Liang Tzu and other places in Shantung.

Bactrian Types.

It has been claimed that the proud horses of these reliefs were of Bactrian origin. This is possible but the Chinese sculptors were certainly less guided by observation of nature than by artistic models, be it in bronze, clay or textile. They have accepted and further developed a definite type of horse which probably existed in the art of the Hellenized west-Asiatic countries.Less Hellenistic and more definitely Scytho-Iranian in char acter are the winding dragons and heraldically placed tigers which appear in one or two of these reliefs. They belong to the same great family of ornamental animals which we also met on the stone pillars in Szechuan, and may thus be said to form some additional proofs of the general acceptance of this kind of animal sculpture during the Han period.

Still more remarkable examples of the same stylistic current are the two lions which stood at the entrance to the tomb of the Wu family (at the sides of the above-mentioned pillars) but which are now more or less buried in the mud. The anatomical character of the only visible one is rather free. It is, indeed, no common lion but a descendant of those proud animals which stood at the royal palaces in Susa and Persepolis and whose artistic pedigree may be traced to Chaldean and Assyrian art. The form is supple, the body is thin, the whole animal is dominated by the broad curving neck which comes so far to the front that the head almost disappears and the neck continues in the enormous jaws. At the shoulders one may observe traces of small wings, though they have been practically worn off by time. Such a crea tion has hardly been shaped from nature. Even if single lions now and then were sent as tributes from western Asiatic nations to the Chinese emperor, these were hardly known by the people in the provinces, and as there were no other lions in China, we may well suppose that the inspiration for such animal representa tion was drawn from examples of Iranian art rather than from living models.

Animal Statues.

To the same group of animal statues from the end of the Han-epoch may also be assigned two winged tigers at the tomb of K'ao Yi at Ya Chou Fu in Szechuan, which have been published by Segalen and Lartigue, and the enormous seated lion—which has served as a plinth for a pillar in the Okura museum in Tokyo. There are furthermore some minor animal statuettes of the same type but they hardly need detain us as they only verify what has already been said about the artistic style and derivation of these sculptures. Nor do we need to stop at the human figures executed in stone on a large scale, because their artistic importance is much inferior to that of the animals.Animal Sculptures of the Six Dynasties Period.—During the centuries which followed the fall of the Eastern Han dynasty (A.D. 214) artistic activity in China lost some of its intensity. The times were restless, filled with war and political upheaval. The empire was again divided into several minor States, to be gin with, the Three Kingdoms, Wu, Shu and Wei, and later on, after 223, into a northern and a southern half, the former being under the domination of the Tartars, among whom the Toba tribe came out the strongest and took the name of the Northern Wei dynasty, while the latter was ruled over by a number of short-lived native dynasties—Sung, Ch'i, Liang and Ch'en which had their headquarters at Nanking. We know very little about the artistic activity during these times but it seems that the stylistic traditions of the Han period remained in force also dur ing the 3rd and 4th centuries of our era. Some tomb reliefs, mainly from Shantung, executed in a kind of coarser Han style, may well be of this transition period, and the same may be said of a number of minor plastic works in bronze and clay.

The general evolution can be followed most closely through the small tomb statuettes; they reflect the variations in taste and fashion better than the large stone sculptures. Among them are real genre figures represented in various occupations such as music-making, feeding the hens, or with children in their arms, and we may observe how the fashion is changed from the simple "kimono" to an elegantly draped mantle over a tightly-fitting undergarment and how the head-dress becomes higher and more decorative. These tomb statuettes and minor animals in terra cotta originate mainly from Honan, whereas the larger stone sculptures of this same period are executed for the reigning dynasties in Nanking. These monuments which form one of the most important groups within the domain of Chinese sculpture, have been more or less identified and reproduced by various explorers.

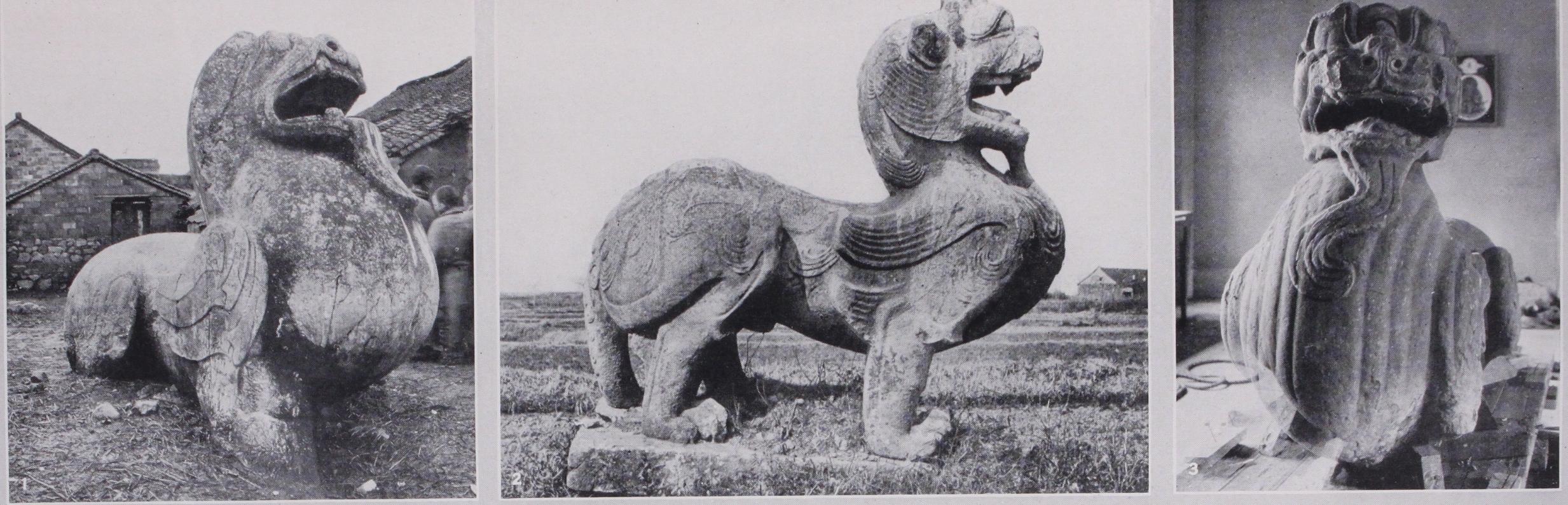

The largest among these lions and chimaeras measure up to I O or I 2 f t. in length and may still be seen at their original places, but some smaller ones, 4 to 6 ft. long, have found their way to Western collections. They all represent winged, lion-like animals but it is possible to distinguish two main types, i.e., the chimaeras, which are a kind of cross between dragons and lions, and the real lions which have wings on their shoulders but no feathers or scales on their bodies and no ornamental beard. The former seem to have been considered the nobler, because they were employed as guardians at the tombs of emperors, whereas the lions stood at the tombs of princes and dukes.

Early Chimaeras.

The earliest chimaera which can be dated stands at the tomb of Emperor Sung Wen Ti (d. 453) . It is a colossal and, in spite of its dilapidation, still imposing animal, largely covered up by a heap of refuse, so that the statue had to be dug out whenever it was photographed. The upper part of the head is lost and the surface of the grey limestone is very much worn but it is still possible to see that the body as well as the legs have been covered by ornamental scales or feathers and that the animal had wings not only at the shoulders but also at the ears.The second earliest in date of the chimaeras which still remain at their original sites is the one at the tomb of Emperor Ch'i Wu Ti (d. 493) . The dimensions are somewhat smaller but the animal is more completely preserved. The long body has a more dragon like character, the legs are comparatively short and the tail well developed. The most imposing part is, however, the enormous head with the open jaws from which the ornamental beard hangs like a long tongue. One may here observe three pairs of wings as well as feathers drawn in spirals over the whole body.

Sixth-century Chimaeras.

The same proud bearing char acterizes the chimaera at the tomb of Emperor Liang Wu Ti (d. 549). The of the long and supple body is still better developed and it receives a most effective continuation in the enormous curve of the neck. The animal is moving forward in an ambling fashion ; we feel its vigour and suppleness. The wings and the feathers are indicated in quite low relief or simply engraved.This nobility and energy are carried still further in the two large chimaeras which now stand in the University Museum at Philadelphia. We have no information whence they come, but they illustrate a further evolution of the style of the chimaeras at the tomb of Emperor Liang Wu Ti, which would date them shortly after the middle of the 6th century. It is possible that they stood at the tomb of some of the emperors of the short Ch'en dynasty which followed after the Liang, such as Ch'en Wu Ti (d. 559) or Ch'en Wen Ti (d. 566). In comparison with these beasts, the earlier chimaeras appear almost like domestic animals. The fantastic wildness and the seething energy are here given free outlet. The legs are stretched, the bodies drawn, the head is wildly thrown backwards, the chest pushed forward into a large curve, and all these movements are accentuated by engraved lines which give the impression of taut steel springs. Besides these large ones several minor chimaeras are known but none of them reaches the extraordinary expressiveness of the last-mentioned.

Winged Lions.—The largest of the winged lions still remain in situ, not far from Nanking; their weight and colossal dimen sions have made their removal impossible, but some of them are so far decayed that, if nothing is done to protect them, they will soon disappear. The earliest and most important stand at tombs of various members of the Liang family, i.e., the brothers of the Emperor Wu Ti, Prince Hsiao Hsiu (d. 518), Prince Hsiao Tan (d. 522) and the cou sin of the emperor, Duke Hsiao Ching (d. 523). Besides these, two or three pairs of large lions are in the same neighbourhood, at Yao Hua Men, to the east of Nanking, but they are later and artistically inferior. The ana tomical difference between the lions and the chimaeras is, as already said, not very important.

The former as well as the latter are feline animals with an enor mous curving neck and wings, but they are not provided with scales or feathers, nor do they have any ornamental beard like the chimaeras, only a large tongue which hangs down from the open jaws over the projecting chest. They are all represented in an ambling posture, majestically walking or coming to a sudden standstill, when the fore-legs are strained and the hind-legs bent. The head is lifted high on the proudly curving neck, the forms are full, the limbs heavier than in the chimaeras. Their massiveness is at least as imposing as the concentration of power in their enormous limbs. Most eaten by frost and water are the lions at the tomb of Duke Hsiao Ching which is now covered by a watery rice field in which the lions sink up to their shoulders.

Lions of Hsiao Hsiu Tombs.—Better preserved and more completely visible are the two colossal lions at the tomb area of Hsiao Hsiu, now covered by the village Kan Yu Hsiang, and here remains one row of the other monuments which flanked the "spirit road," i.e., two large tablets with inscriptions carried by tortoises and a fluted column on a plinth composed of winding dragons. This seems to be the earliest preserved "tomb alley" in China, an arrangement known from a great number of later tombs. The lions are of the same family as those already de scribed, the fact that they have wings is in itself a proof of their dependence on Persian art. It should, however, be remembered that the Achaemenian and Sassanian animals were descendants of the Assyrian which must be regarded as the fore-fathers of all the greatest Asiatic and a good many European lion sculptures. To what extent the Chinese really knew such models is a ques tion which cannot be discussed here ; it is in any case evident that they transformed the foreign models quite freely, not to say fantastically, in harmony with their native traditions. These animal sculptures form stylistically a direct continuation of the plastic art of the Han period. Yet, they indicate that a new wave of Western influence reached China at this time on a more south ern route than through the north-western nomads. These lion sculptures do not appear in the northern provinces which were dominated by the Tartars. They belong to the more southern provinces where the old Chinese civilization and the creative spirit of the "Han people" never were completely subdued by foreign elements.

Religious Sculpture of the Six Dynasties.

When Bud dhist sculpture was introduced into China it had passed through a long evolution in India and Central Asia ; the principal icono graphic motives, symbols and attributes were all developed into definite forms; the Chinese took them over just as they took over Buddhist scriptures; and whatever modifications they may have introduced concerned more the artistic interpretation than the motives themselves. It should never be forgotten that they were greater artists than any other people of the Far East, and when Buddhist art took root in China, the country was by no means devoid of sculptural monuments. There were (as we have pre viously seen) artistic traditions which could not be forgotten, only modified when applied to Buddhist motives. The Buddhas and Bodhisattvas were, of course, represented in human shapes but the artists could not enhance their significance by accentuating their physical organisms or their likeness to ordinary human be ings, nor could they change their general shapes or postures if they wanted to be understood. The iconographic rules are indeed much more exacting in Buddhist than in Christian art, and the motives are more limited in their artistic scope.

Religious Symbolism.

The great majority of the Buddhist sculptures represent isolated figures, seated or standing in very quiet postures without any attempt at movement, except certain symbolic gestures. The heads are made according to quite definite types, somewhat changing with the periods and localities, but it is rare to meet heads with individual expression or portraitlike features. The bodies are as a rule entirely covered by long mantles or rich garments according to the role or meaning of the figure; they have hardly any importance of their own but serve simply as a substratum for the rich flow of the mantle folds which, particularly in the early sculptures, conceal the forms much more than they accentuate them. Even in figures which are represented almost nude, such as the guardians at the gate (Dvarapalas), the representation is not really naturalistic ; their Herculean forms and muscular movements are altogether exaggerated and their significance is symbolic.The earliest dated Buddhist sculptures in China, known to us, are small bronze statuettes of a greater historical than artistic im portance. Some of them are provided with inscriptions which make it possible to fix their date, the earliest being of the years 437 and 444, whereas the earliest dated Buddha in stone is of the year 457. These small statuettes represent standing or seated Buddhas or Bodhisattvas against a leaf-shaped nimbus decorated with engraved flame-ornaments. The figures are mostly of a very moderate artistic importance recalling by their types and draperies the Graeco-Buddhist art of north India. The large nimbuses behind these small figures constitute, however, a feature which is not known in Gandahara sculpture.

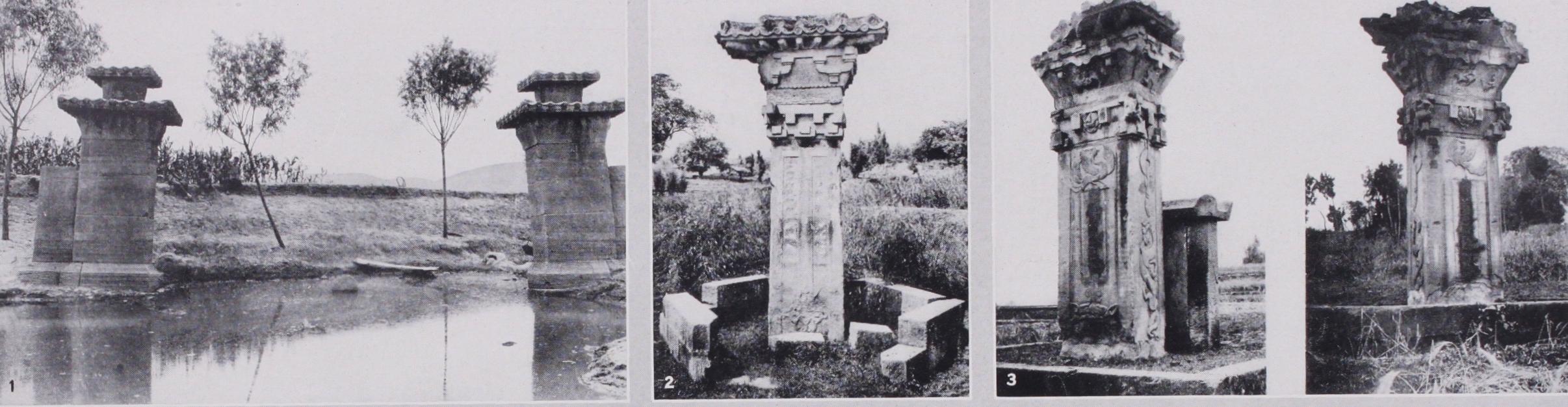

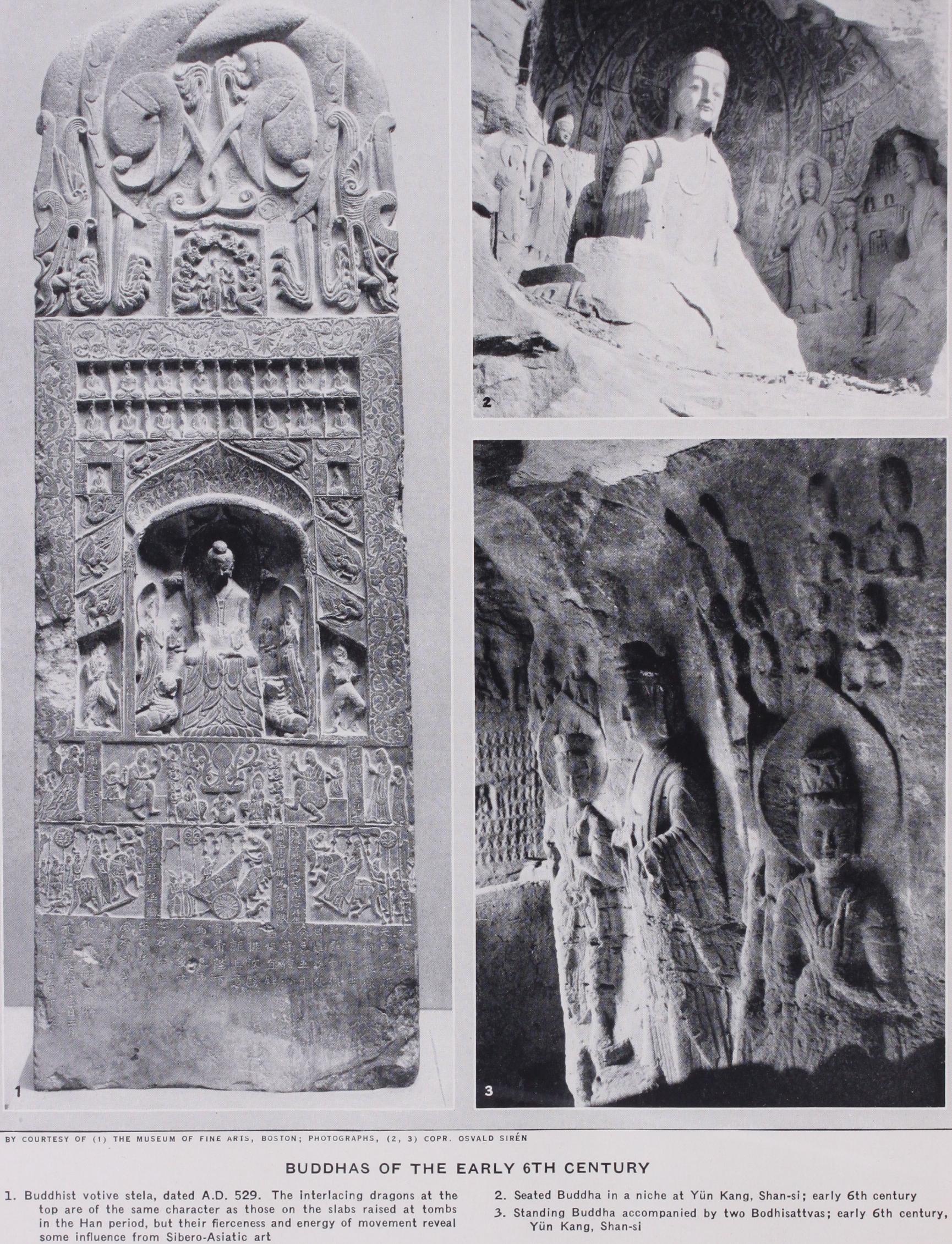

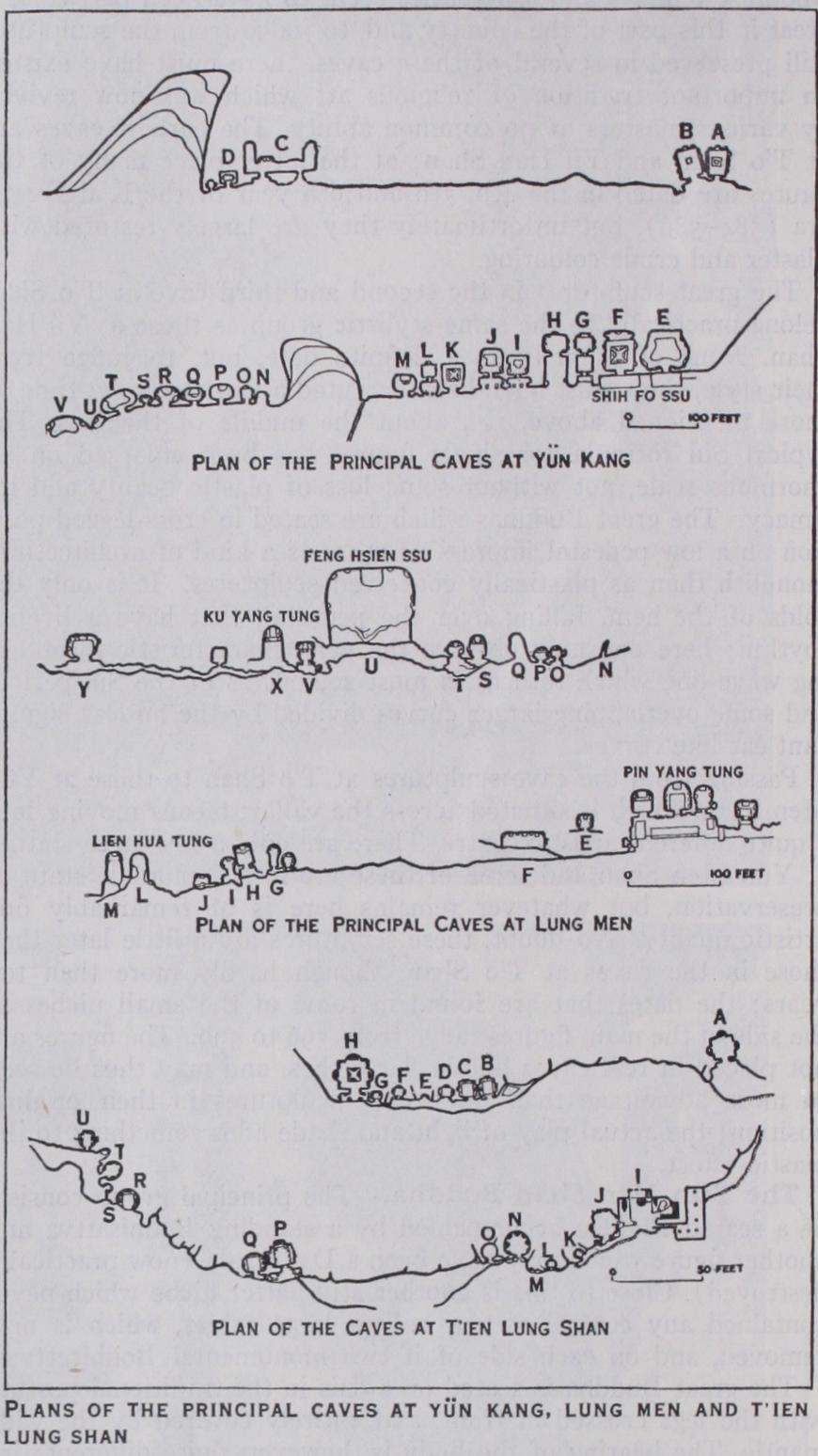

Yiin Kang Cave Temples.

The greatest ensemble of early Buddhist sculptures in China is to be found at the Yiin Kang cave temples near Ta Tung Fu in Shansi where the Northern Wei dynasty had its capital until 494, when it was removed to Loyang in Honan. The work at these cave sculptures started about the middle of the 5th century and was continued towards the latter part of the 6th century. Amongst the rich material displayed at this place one may observe different stylistic cur rents, some originating from Central Asia and India, others more closely connected with earlier forms of Chinese art. Here are ornaments of a distinctly Iranian character, and architectural forms of the same type as on reliefs from Taxila and Peshawar, but also some decorative motives recalling the art of the Han period. Among the figures there are some curious examples which form a' link with Central Asiatic art, e.g., the five-headed and six-armed god who sits on a large bird with a pearl in its beak. This is no doubt the Garuda-raja, the bird of Vishnu, which also may be seen in some paintings from Tun Huang. This and other Hindu divinities of a similar kind, which appear in the Buddhist pantheon at Yiin Kang, testify that artistic influence from central and western Asia reached China in connection with the introduc tion of Buddhism.

Artistic Expression.

Most famous among the figures here are the colossal Buddhas and Bodhisattvas which, however, seem to us artistically least interesting. A certain conventional type and fold design have in these figures been enormously enlarged without any intensification of the rhythmic motives or the ar tistic expression. More artistic expression and beauty may be found in some other figures at Yiin Kang which are less closely allied to Indian models and more imbued with the traditional Chinese feeling for rhythmic lines and elegant form. The figures themselves are quite thin and flat, sometimes hardly modelled into full cubic volume, and they are entirely covered up by very long and heavy garments. The f olds of these are pressed and pleated on the very thin shapes and uniformly arranged on both sides of the figures in long concave curves, forming a kind of zigzag pattern at the border ; the contours are very tense, with the elasticity of drawn bow-strings. When this type of draping is fully developed the drawn out, curving mantle-folds may suggest wings.

Temple Grottoes at Lung Men.

The same energetic style as in the best Yiin Kang sculptures may also be observed in some of the statues in the famous temple grottoes at Lung Men in Honan which were begun shortly after the Northern Wei dynasty had transferred its capital to Loyang (494)• During the last decade these caves have been so badly destroyed that hardly of the original sculpture still remains ; all the rest is either smashed or beheaded, some of the heads being replaced by clay substitutes of a very provincial type. The most beautiful and earliest sculp tures at Lung Men are to be found in the so-called Lao Chun Tung cave which is decorated from ceiling to floor with a great number of niches of varying sizes in which Buddhas and Bod hisattvas are grouped, either alone or together with adoring bik shus or other attendants. The majority of these sculptures were executed in the 3rd or 4th decade of the 6th century, but only some of the minor reliefs remain still in a fair condition. Yet some characteristic positions may be observed, for instance the cross-ankled Bodhisattvas which represent Maitreya, the coming Buddha, while the Buddha Sakyamuni is seated with legs straight down. The stylization of the folds is carried out according to the same patterns as in the Yun Kang caves, but the stone is harder and the technique is superior to that of the earlier Yiin Kang sculptures. Some of these Lung Men sculptures have cer tainly been among the finest works of their kind in China.Another variation of the Northern Wei period style may be observed in the sculptures which decorate the temple caves at Shih Ku Ssu, near Kung Hsien in Honan. The work was here started about the same time as at Lung Men but the material is of a softer kind and the technique is not quite so fine. The large central Buddha at this place, which now stands up to its knees in mud, is a broad and block-like figure modelled in very large planes, with a remarkable cubistic tendency, which also may be observed in several minor heads from the same place, now dispersed in various European and American museums.

Buddhist Stelae.

Besides these cave sculptures of the Northern Wei period should be mentioned a large number of Buddhist stelae, i.e., slabs with figures in high relief, varying in size, some up to 12 ft. high, others quite small. Their decoration consists generally of a combination of niches with Buddhist figures and ornamental borders. On the back of these slabs are often found long rows of figures in flat relief representing the donors of the monuments. This form of stelae was probably de veloped from the earlier type of inscribed memorial stones, as used in China since the Han dynasty. It is worth noticing that we find at the top of the Buddhist stelae the -same kind of wind ing and interlacing dragons as on the slabs which were raised at the tombs; their fierceness and energy of movement seem to reveal their derivation from the Sibero-Asiatic art, based on Scythian traditions which, indeed, had a great influence on the development of the ornamental style of this period.

Transition Period.

The stylistic ideals of the Northern Wei period retained their importance until the middle of the 6th century. About this time a new wave of artistic influence reached China from northern India. It may be quite clearly observed in some of the monuments which were executed during the Northern Ch'i and Northern Chou dynasties (550-581). The best cave sculptures from this time existed, at least a few years ago, at T'ien Lung Shan not far from Taiyuan-fu in Shansi. They were started in the Northern Ch'i period and continued, with some intermissions during the Sui and T'ang dynasties.

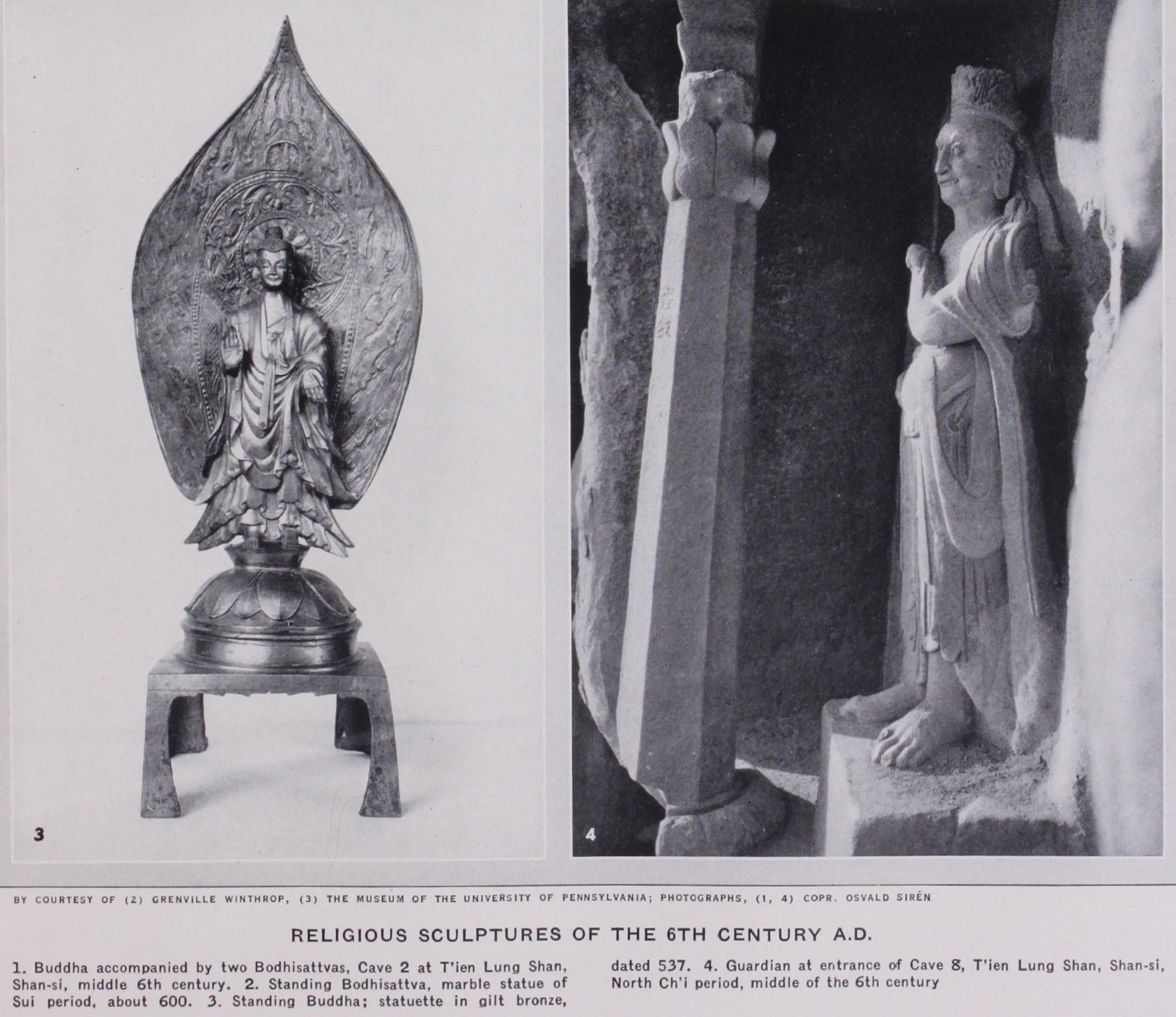

Sculptures at T'ien Lung Shan.

The earliest sculptures at T'ien Lung Shan are to be found in the caves no. 2, 3, 10 and 16, probably executed between 56o and 580. The system of decoration in the first two caves consists of three large groups, one on each wall representing a seated Buddha accompanied by two Bodhisattvas and, in some instances, also by adoring monks and donors, characterized with striking realism. The main figures are executed in very high relief, giving almost the impres sion of free-standing forms, yet there is a certain flatness about them, noticeable particularly in the Bodhisattvas which stand turned half-way towards the central Buddha and whose garments —arranged in pleated folds—spread out in wing-like fashion at the sides. They are not very far removed stylistically from cor responding figures on later Wei monuments, though their heads are less archaic both in shape and expression.The maturest examples of this transition period—possibly executed as late as 58o—are to be found in the i6th cave at T'ien Lung Shan, where all the three walls are decorated with large groups of Buddhas with Bodhisattvas and other attendants placed on raised platforms, the fronts of which were decorated with repre sentations of dwarf musicians. The central Buddhas are lifted into commanding positions on high pedestals in the form of lotus flowers or altars ; their shapes are full and well rounded, their heads comparatively small for the strong bodies. They are all seated in the same cross-legged posture, with bare feet and hands in the abhaya and vara mudra (gestures signifying "without fear" and "charity") . Their mantles, which are made of a very thin material, are draped only over the left shoulder, leaving the right bare, and the folds have practically no relief. Buddhas clothed in this fashion are very rare in Chinese art; they may occasionally be found in later T'ang sculpture but at this early period they are certainly surprises.

Foreign Influence.

The most probable explanation of this apparent anachronism in the style of the Buddhas seems to be that they were made from foreign models or by foreign artists while the less important side figures were carved in accord ance with the indigenous principles of style. The figures are alto gether Indian in spirit and form. It is hard to believe that Chinese artists would have been able to reproduce Mathura models so faithfully as we find them here, and it may at least be claimed that they have never done it better, either before or after. Possibly some Indian artist, well acquainted with the Mathura school, worked for some time at T'ien Lung Shan.The same general types and principles of style which character ize the sculpture at T'ien Lung Shan may also be found in some isolated statues coming from this or a similar centre of sculptural activity. The most characteristic feature of all these figures is the cylindrical shape indicated in the legs and arms, as well as in the shape of the whole body, which often stands like a column on the lotus pedestal. Nothing can be more unlike the compara tively flat and angular shapes of the Northern Wei figures, which even when they have a more developed plastic form are linear rather than rounded.

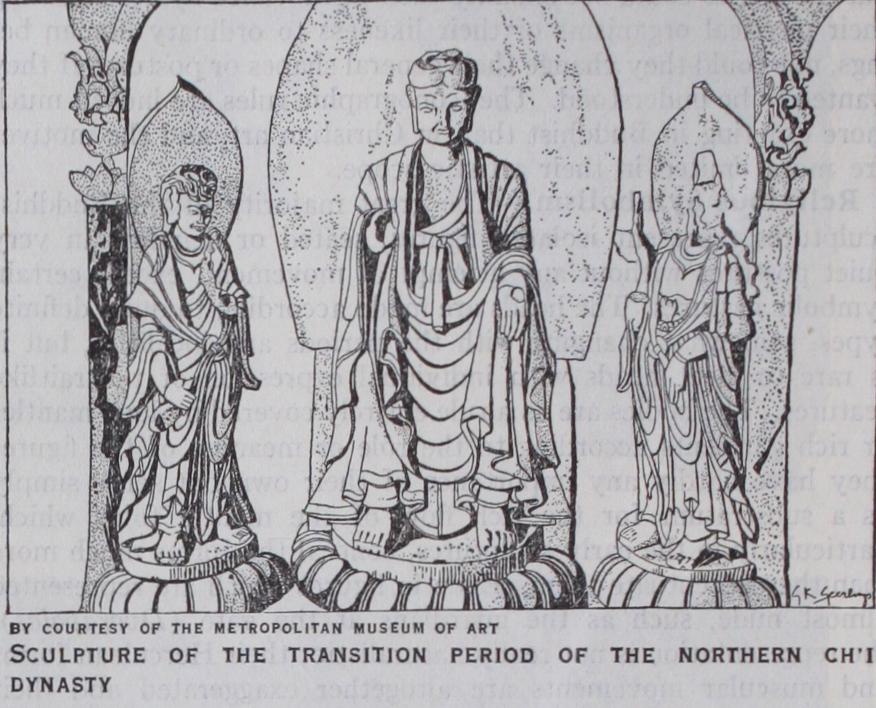

Sculptures from Chihli Province.

Another provincial vari ation of the transition style may be seen in the sculptures from Chihli, the present metropolitan province, and particularly from Ting Chou where the supply of a beautiful white marble was abundant. The artistic quality of these sculptures is however quite uneven; the best of them stand on the highest level of Buddhist art in China, while the poorest are hardly more than ordinary artisans' work. Several figures of this group might be quoted as proofs of what already has been said about the plastic formula during this transition period. Their shapes are more or less cylindrical, their heads mostly large and heavy. One may notice a general tendency to make the figures narrower towards the feet and to broaden them towards the shoulders. The thin garments fit tightly over the bodies and their softly curving folds are indi cated in quite low relief or simply with incised lines. Good ex amples of such statues are in the Metropolitan Museum in New York. If we place such a figure beside some characteristic example of the Northern Wei art, we may observe two opposite tendencies of style. In the earlier works the mantle folds and the contours are stretched and bent outward at the feet, the shoulders are narrow, the heads small; the rhythm is rising. In the later ones the rhythm is falling instead of rising, the tempo is slow, not without heaviness; there is no bending of the contours, they are falling almost straight down; the mantle hangs over the body and it is only towards the feet, where the circumference be comes smaller, that a certain acceleration of the tempo is notice able.

The Sui Dynasty.

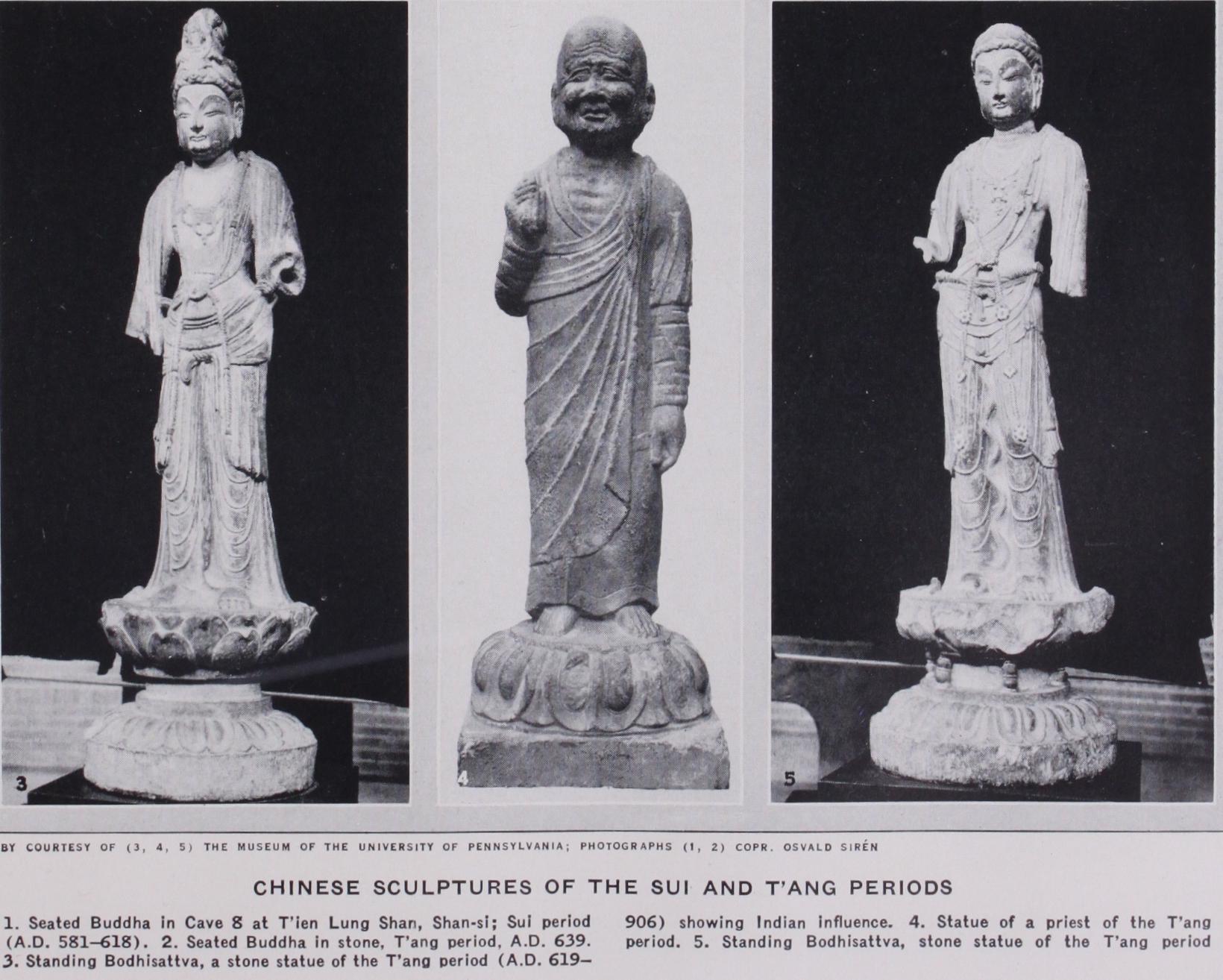

The sculptures of the Sui period (581 6 i 8) form, stylistically, a direct continuation of those of the transi tion period during the Northern Ch'i and Chow dynasties. Most of them are still examples of the transition style, but a few may well be classified among the most perfect works of religious statuary in China. Conditions were particularly favourable for the flourishing of religious art, and the formal development had not yet passed the point where it becomes an end in itself. Sui sculp ture is, on the whole, quite restrained in its formal modes of ex pression and its interest in nature is slight, but it marks neverthe less a distinct progress in the representation of actual forms.

T'ien Lung Statues.

Some good examples of the particular style of this period are to be found in the 8th grotto at T'ien Lung Shan which is in part preserved, although the soft material has been worn by time and water and some of the statues have been smashed and decapitated. Coming to these statues from a study of the sculptures in cave i6 at the same place (mentioned above), the first thing that strikes one is that they are not at all Indian in their general appearance. The Buddhas are seated in the same postures as the earlier ones but vested in the Chinese fashion with an upper garment covering both shoulders and with a less hieratic bearing of the stiff bodies. The shoulders are not so broad, the waist less curving, the forms are quite undifferentiated, but the heads have increased in size and have a more human air. They are certainly more Chinese, though in a provincial sense, and they are executed by inferior artists with little feeling for rhythmic lines and decorative beauty.Most interesting are the two pairs of Dvarapalas (guardians) outside this cave. One pair is placed at the sides of the entrance, the other at each side of a tablet near by which still contains traces of an inscription of the Sui dynasty (said to have been dated 584). The attitudes of these guardian figures are highly dramatic, not to say strained. The movement of the arms is jerky, the turn ing of the heads, which are looking over the shoulder, is violent. The impetuosity is, indeed, much greater in these figures than in the Dvarapala statues at the earlier caves, but whether they have gained in sculptural quality as much as in dramatic force is less certain.

Typical expressions of the plastic formula of the Sui period are also to be found among the sculptures from Chihli, easily recognizable by their material which is a micaceous white marble. Common to them all is the general shape which is no longer simply pillar-like or cylindrical, but ovoid. The contours are swelling out over the hips and elbows and gradually draw closer toward the feet and over the head. Thus a general formula is created, and it is often repeated on a smaller scale in the heads. The same rhythm is taken up by the folds which in some of the figures form a suc cession of curves over the front endowing them with a more com plete harmony and repose than may be expressed by any other shape or formula known to us.

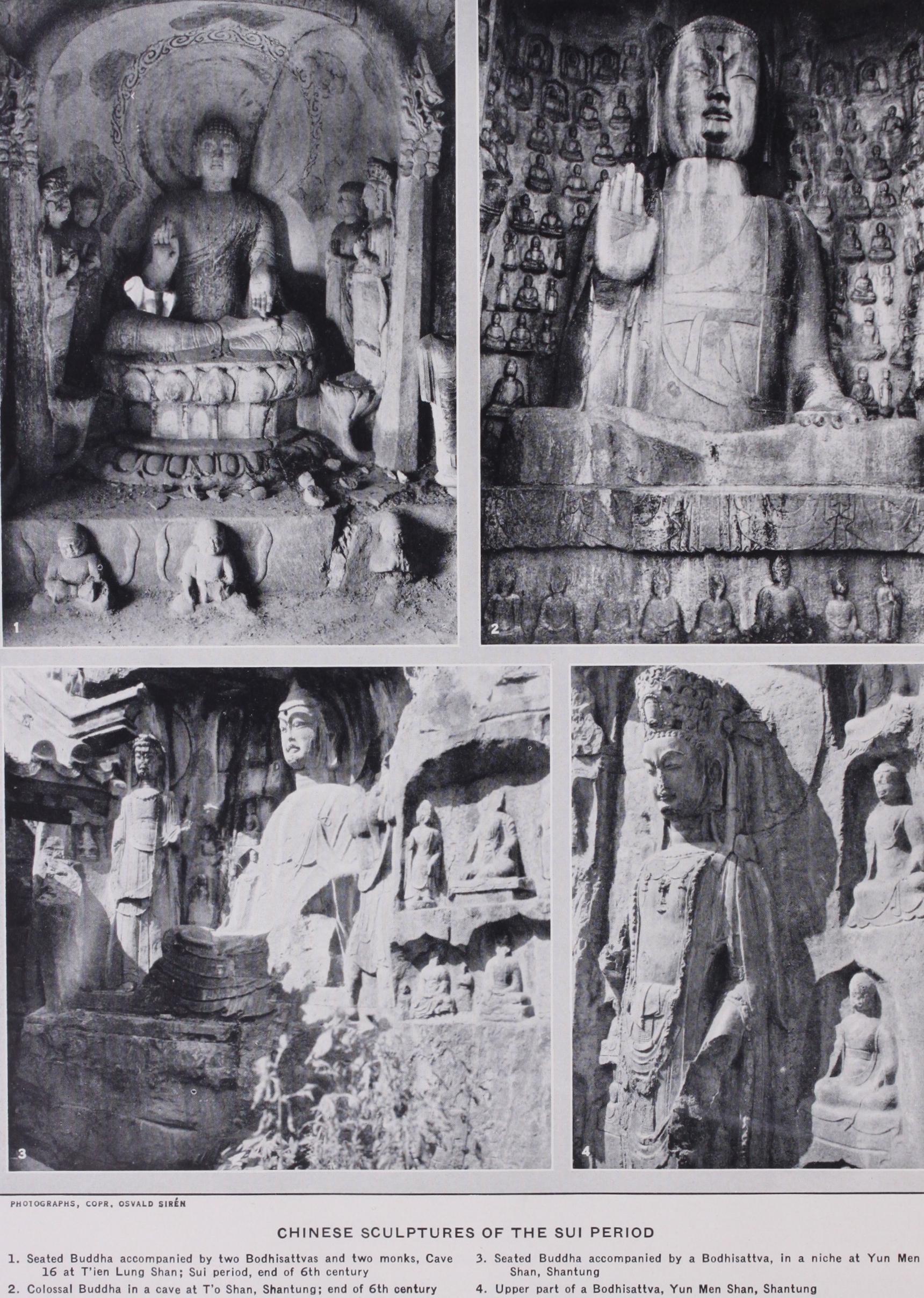

Shantung Sculptures.

The richest and most varied provin cial group of sculptures from the Sui period is to be found in Shantung. The religious fervour and interest in establishing Buddhist temples and sanctuaries seem to have been particularly great in this part of the country and, to judge from the sculptures still preserved in several of these caves, there must have existed an important tradition of religious art which was now revived by various masters of no common ability. The earliest caves are at T'o Shan and Yu Han Shan ; at the latter place many of the figures are dated in the 4th, 5th and 6th year of the K'ai Huang era (584-586), but unfortunately they are largely restored with plaster and crude colouring.The great sculptures in the second and third cave at T'o Shan belong practically to the same stylistic group as those at Yu Han Shan. None of them bears a definite date, hut, to judge from their style, they must have been executed about the same time as those mentioned above, i.e., about the middle of the '8os. The typical Sui formula for single figures has been enlarged on an enormous scale, not without some loss of plastic beauty and in timacy. The great Buddhas which are seated in cross-legged posi tion on a low pedestal impress us more as a kind of architectural monolith than as plastically conceived sculptures. It is only the folds of the hem, falling over the pedestal, that have a livelier rhythm ; here one may observe the very characteristic meander ing wave-line which returns in most sculptures of the Sui period, and some overlapping larger curves divided by the no less signifi cant ear-like curves.

Passing from the cave sculptures at T'o Shan to those at Yiin Men Shan, which is situated across the valley, means moving into a quite different artistic centre. There are only a few large statues at Yun Men Shan and some of these are in a deplorable state of preservation, but whatever remains here is of remarkably fine artistic quality. No doubt, these sculptures are a little later than those in the caves at T'o Shan, though hardly more than ten years ; the dates that are found in some of the small niches at the side of the main figures range from 596 to 599. The figures are not placed in real caves but in flat niches, and may thus be seen to more advantage than most cave sculptures in their original position ; the actual play of light and shade adds something to the plastic effect.

The Yiin Men Shan Buddha.

The principal group consists of a seated Buddha accompanied by a standing Bodhisattva and another figure which may have been a Dvarapala (now practically destroyed). Close to this is another still flatter niche which never contained any central statue, only a large tablet, which is now removed, and on each side of it two monumental Bodhisattvas.The great Buddha is seated on a dais in the traditional posture with the legs crossed in front, and entirely covered by the wide mantle. The bearing of the body is, however, quite different ; in stead of the old stiffness there is a certain ease in the posture, a repose without any strain. He seems to lean against the wall of the niche, moving the head slightly forward as if intent on looking at something in front. The upper garment which is fastened with a string knot on the left shoulder is draped in quite broad curves between the knees. The folds are not simply ornamental or expressive of a linear rhythm, but modelled with fine gradations of light and shade, sometimes even undercut. They have become means of primary importance for creating a sculptural effect. The head is treated in a new individual manner with broad effects of light and shade. The eyes are not closed or half closed, as in most of the earlier Buddhas, but wide open, and the eyelids are undercut, which adds greatly to the impression of life. The lips are also separated by a deep shadow, as if they were opening. The whole treatment is quite exceptional and bears witness to an impressionistic style; strictly speaking, it remains an isolated phenomenon in Chinese sculpture.

The T'ang Dynasty.

It would indeed be wrong to imagine that there is an absolute break or a deep-rooted difference between the sculpture of the Sui and that of the T'ang period; quite the opposite. T'ang sculpture is stylistically an immediate successor to the art of the Sui period. When we, for convenience sake, use the dynastic names and dates also in the domain of art, it should be clearly understood that they do not signify here the same kind of opposites or renewals as in the political history of the country. Artistic evolution in China is a slow and gradual process, which only to a minor degree is conditioned by the political events.It may also be recalled that the T'ang dynasty reigned during a longer time than most of the preceding dynasties (619-960), and the plastic arts remained by no means the same during this whole period. The production of sculpture was very intense dur ing the first i oo years of the period, but became soon afterwards comparatively weak and insignificant. In speaking about T'ang sculpture we mean the art up to about 725, which may be con sidered the most mature and perfect kind of Buddhist sculpture in China. It reflects something of the same creative and expansive power that we may observe in other manifestations of Tang culture. Its best products are characterized by a plenitude, not to say magnificence, that can hardly be found in the art of earlier epochs. The forms grow full and strong, the decoration becomes rich and exuberant, gradually approaching what we should call baroque.

An important element in this evolution was due to the growing inter-communication between China and the western Asiatic centres of artistic activity, particularly the Sassanian empire. Many new impulses were derived thence and grafted upon the old stock of Chinese art, modifying it more and more in the direction of Western ideals of style. Generally speaking, it may be said that the current that came from India was of the greatest impor tance for the Buddhist sculpture, while the influences from Persian art are most plainly discernible in the ornamentation of minor objects in bronze and silver.

In order to illustrate these two main currents, as well as other important elements of style in the plastic art of the T'ang period, it would be well to take into consideration other artistic products besides stone sculptures, such as objects in bronze, silver, clay and lacquer, which reflect the aesthetic ideals of the time, but this would carry us beyond the limits of this short study. Buddhist statues still form the most important province within the plastic arts of the T'ang period, though it should also be remembered that some large tomb sculptures were executed at this time, includ ing magnificent representations of lions and horses at the tombs of the great emperors, T'ai Tsung (d. 649) and Kao Tsung (d. 683) .

The Shensi Sculptures.

The early T'ang sculptures from Shensi, which then was the metropolitan province, are made in a very hard, grey limestone or in a dense yellowish marble. The fine quality of the material demands a highly developed technique in order to yield good plastic effects and ornamental details, and it may well be admitted that as far as workmanship goes many of these statues stand on the highest level of Chinese sculpture, but the artistic quality is often less remarkable. The earliest dated statue of this period known to us is of the year 639; it represents a Buddha seated in cross-legged position on a high, draped pedestal placed in front of a background slab which is bordered like a nimbus with flame ornaments. The figure is draped in a mantle which covers both shoulders, arms and feet, leaving only a small part of the chest bare. The folds are highly conventionalized in the form of thin, rounded creases and arranged in long curves over the body, the legs and the upper part of the pedestal. The decorative effect is altogether more powerful and concentrated than in earlier statues of a similar kind, and the execution is masterly. Although made in stone, the statue gives the impression of a work cast in bronze, an impression which is supported by the dark metallic hue of the hard stone.

Influence of Indian Art.

Some Bodhisattva statues, of which two may be seen in the University museum in Philadelphia, illus trate still better an increasing influence from Indian art not only by their costumes and decorative ornaments but also by their bearing and formal character. They stand no longer in stiff up right positions with the weight of the body evenly divided on both feet ; the one leg is slightly curved and moved backward, the other serves as a support for the body which consequently is curving, a movement which is continued in the neck and in the more or less marked inclination of the 'head. The upper part of the body is bare, except for the jewelled necklaces and the narrow scarf draped over the shoulder; the chest is well developed and the waist rather narrow. The dhoti, which is tied with a sash round the hips, falls in a series of curving folds over each leg, and these are indicated in the same fashion as the folds of the Buddha men tioned above. It should also be noticed that these figures do not wear a crown or a diadem on their heads like the early Bodhisatt vas, but a high head-dress made up of thick winding plaits, a fea ture which also adds to their feminine aspect.A kind of masculine pendant to these Bodhisattvas may be found among the statues of bikshus or monks, executed either as individual post mortem portraits or as parts of altar groups (examples of such statues may be seen in the museums in Philadel phia and Boston). They are less conventionalized, less dependent on foreign models and made in closer adherence to actual life. Their heads are portrait-like, their mantles arranged in a more or less natural fashion, thus, in many instances, approaching the small clay statuettes made for the tombs during the T'ang period as well as in earlier times. Some of these portrait statues may indeed be placed on a level with the best Roman sculptures. They are character studies, not so far individualized as Renais sance portraits, but very striking types, observed in actual life. It is also worth noticing how much freer and more plastic the draping of the mantle becomes in these statues. A figure such as the headless monk in the Boston museum might have been made by a Roman artist.

Honan Sculptures.—When we pass from the metropolitan province of Shensi into the adjoining province of Honan we may at once observe that the general character of the sculptures be comes modified. The provincial schools and stylistic differentia tions seem on the whole to have become more developed at this time than at earlier epochs; it is now easier to distinguish the provincial currents.

The statues made in Honan, and particularly at the great artis tic centre of Lung Men, where the decoration of the caves was continued during the 7th century, are generally more elegant than those originating from Shensi, though not always executed in such perfect technique. Unfortunately, the great majority of the early Tang sculptures at Lung Men are partly or wholly de stroyed—the heads being dispersed all over the world—so that it is now next to impossible to find there complete and good speci mens of moderate size; we find them more easily in museums and private collections.

One of the finest examples is a large Bodhisattva statue, origi nally at Lung Men, but now in private hands in Peking. It may be taken as a representative of a large group of standing Bodhisattvas which all show the Indian influence grafted in Chinese types and shapes, a combination which in this particular instance has led to a perfectly harmonious result. The whole figure from the head dress down to the feet is dominated by the softly gliding move ment of the double S-curve (as in some Gothic madonnas) which would appear almost too accentuated, if it were not so perfectly balanced by the position of the arms. The contemporary Bodhi sattvas from Shensi, represented in a similar position, appear quite stiff and hard beside this elegant and yet so dignified figure.

The Vairochana Buddha.—The colossal statues on the open terrace, which rises above the river at Lung Men, reflect in the most monumental form the religious pathos of the fully developed Tang art. This is true particularly of the central figure, the great Vairochana Buddha; the side figures, two Bodhisattvas and two bikshus are decidedly inferior. The hands are destroyed, the lower part of the figure has suffered a great deal, but I doubt whether it ever made a stronger impression than to-day when it rises high and free in the open air over the many surrounding niches in which time and human defilers have played havoc with most of the minor figures. The upper part of this giant is well preserved and more dominating now than ever. Long ages have softened the mantle folds and roughened the surface of the grey limestone which is cracking all over, but they have not spoilt the impression of the plastic form. It may still be felt under the thin garment : a very sensitively modelled form, not a dead mass, though unified in a monumental sense. According to the inscription on the plinth the statue was made about 672-675.

The great power which is here reflected in such a harmonious and well-balanced form finds further dramatic expression in the Dvarapalas which stand at the entrance to the so-called "lion cave." The bestial heads of the figures are amazing and terrible, and even the naked form is by no means represented from a naturalistic point of view, but as a symbol of strength and vigilance. Other Dvarapalas of the same date are sometimes repre sented in livelier postures, bending sideways or lifting one hand to deal a killing blow to any approaching enemy. The plastic effect is decidedly of a baroque nature, a tendency which is char acteristic of the mature T'ang art whenever it leaves the well trodden path of the traditional religious imagery and ventures on more naturalistic and dramatic representations.

Later T'ien Lung Shan Sculptures.—Another fairly homo geneous local group of T'ang sculpture may be observed in some of the later caves at T'ien Lung Shan where the artistic activity must have been kept up ever since the middle of the 6th century. During all these generations T'ien Lung Shan seems to have re mained a special centre of Indian influence. Unfortunately, none of these sculptures is dated, and in some respects they fall outside