Choking

CHOKING, the obstruction of a passage. In animals chok ing is an obstruction of the windpipe (q.v.) and may lead to suffocation (q.v.; see also LARYNGOTOMY; and TRACHEOTOMY).

In electricity, a choking coil is designed so that it will pass alter nating currents of low but not of high frequencies (see RADIO RECEIVER). In internal combustion engines (q.v.) a choke-tube is a constriction in a pipe, which increases the velocity of the fluid in its neighbourhood and thus reduces the pressure (see HYDROMECHANICS : Bernonilli's Theorem) ; this results in the liquid from the carburettor being sucked into the tube. CHOLERA, the name formerly given to two distinct diseases, acute infective enteritis and Asiatic cholera but now restricted to Asiatic cholera alone. Although essentially different in causa tion and pathological relationships, these two diseases may in in dividual cases present many symptoms of resemblance.

Acute Infective Enteritis

(synonyms, cholera nostras, simple cholera, Cholera Europaea, British Cholera, Summer or Autumnal Cholera) is the cholera of old medical writers. Its occurrence in an epidemic form was noticed in the 16th century. The chief symptoms ih well-marked cases are vomiting and purging occur ring either together or alternately. The seizure is usually sudden and violent. The diarrhoea is attended with severe griping ab dominal pain, while cramps affecting the legs or arms greatly intensify the suffering. In unfavourable cases, particularly where the disorder is epidemic, death may result within 48 hours. Generally, however, the attack is arrested and recovery soon follows, although irritability of alimentary canal may remain for some time, rendering necessary the utmost care in diet. Attacks of this kind are frequent in summer and autumn in almost all countries. Occasionally the disorder prevails so extensively as to constitute an epidemic. The exciting cause conveyed by food or water is bacterial, B. Enteritidis (Gaertner) or an allied form being responsible for the majority of cases. The symptoms are those of toxic poisoning and collapse from loss of fluid. Hence the resemblance to Asiatic cholera.

Treatment.

Vomiting and diarrhoea are natural means where by the harmful material is ejected, but if excessive must be controlled by opiates. Ice and effervescing drinks quench thirst and subdue sickness. Counter-irritation by mustard or turpentine over the abdomen is of use, as is friction with the hands where cramps are present. Food should be whey or albumin water. Ire young children reliance is placed on chalk and starch enemata; opium is dangerous.

Asiatic Cholera

(synonyms, Malignant Cholera, Indian Cholera, Epidemic Cholera, Algide Cholera) is one of the most severe and fatal diseases. Three stages are usually described but often they cannot be distinguished. The first stage is characterized by mild and painless diarrhoea. This generally lasts for two or three days, and then may gradually subside or pass into the more severe phenomena characteristic of the second stage, or may itself prove fatal. This stage may pass unnoticed.The second stage is that of collapse or the algide or asphyxial stage. Not infrequently this stage is the first to manifest itself. Often it starts suddenly in the night with diarrhoea of the most violent character, the matters discharged being whey-like ("rice water" stools). They contain large quantities of disintegrated epithelium from the mucous membrane of the intestines. The discharge, which is at first unattended with pain, is soon succeeded by copious vomiting of matters similar to those passed from the bowels, accompanied by severe pain at the pit of the stomach, and intense thirst. The symptoms now advance with rapidity. Agonizing cramps of the legs, feet and abdominal muscles and signs of collapse supervene. The surface of the body becomes cold and blue or purple, the skin is dry and wrinkled, the features are pinched and the eyes deeply sunken, the pulse at the wrist is imperceptible, and the voice is reduced to a hoarse whisper. There is complete suppression of the urine. In this condition death of ten occurs in less than one day, but in epidemics cases are frequently observed where the collapse is so sudden and complete as to prove fatal in one or two hours even without any great amount of previous purging or vomiting. In most instances the mental faculties are comparatively unaffected, although towards the end there is in general more or less apathy. Reaction, how ever, may take place, and this constitutes the third stage. It consists in arrest of the alarming symptoms characterizing the second stage, and gradual but evident improvement in the patient's condition. The urine may remain suppressed for some time, and on returning is often albuminous. Even in this stage, however, the danger is not past, for fatal relapses sometimes occur or reaction may be so imperfect that death from exhaustion may occur two or three weeks from the commencement of the illness. The bodies of persons dying of cholera remain long warm, and the temperature may even rise after death. Peculiar muscular contractions have been observed after death, so that the position of the limbs may become altered. The soft tissues are dry ' and hard, and the muscles dark brown. The blood is tarry in character. The upper portion of the small intestines is generally found dis tended with the rice-water discharges, the mucous membrane is swollen, and there is extensive loss of its epithelium. The kidneys are usually in a state of acute congestion.

The cause of Asiatic cholera is a micro-organism identified by Koch in 1883 (see PARASITIC DISEASES). For some years it was called the "comma bacillus," but it was subsequently found to be a vibrio, not a bacillus. Apparently there are many strains of the vibrio which differ widely in toxicity and other characters. Probably this explains the great variations in epidemics.

Cholera is endemic in the East from Bombay to southern China, but its chief home is British India. It principally affects the allu vial soil near the mouths of the great rivers, particularly the delta of the Ganges. Lower Bengal is pre-eminently the standing focus and centre of diffusion. In some years it is quiescent, though never absent; in others it passes its natural boundaries and is carried east, north and west, it may be to Europe or America. The micro-organism is carried chiefly by infected persons moving from place to place ; but soiled clothes, rags and other articles that have come into contact with persons suffering from the disease may be the means of conveyance to a distance. There is no reason to suppose that it is air-borne, or that atmospheric influences have anything to do with its spread, except in so far as meteorological conditions may be favourable to the growth and activity of the micro-organisms. Beyond all doubt, the great culture ground of the vibrio is the human body, and the discharges from it are the great source of contagion. They may infect the ground, the water, or the immediate surroundings of the patient, the poison finding entrance into the bodies of the healthy by means of food and drink which have become contaminated in various ways, e.g. by flies. Of all the means of local dissemination, contaminated water is the most important, because it affects the greatest numbers, particularly in places with a public water supply. All severe outbreaks of an explosive character are due to this cause. It is also possible that the cholera poison multiplies rapidly in water under favourable conditions, and that a reservoir, for instance, may form a sort of forcing-bed. But it would be a mistake to regard cholera as purely a water-borne disease, even locally. It may infect the soil in localities which have a perfectly pure water-supply, but have defective drainage or no drainage at all, and then it will be found more difficult to get rid of, though less formidable in its effects, than when the water alone is the source of mischief. In all these respects it has a great affinity to enteric fever. With regard to locality, no situation is secure against attack if the disease is introduced and the sanitary conditions are bad; but, speaking generally, low-lying places on alluvial soil near rivers are more liable than those standing high or on a rocky foun dation. Of meteorological conditions it can only be said with cer tainty that a high temperature favours the development of cholera, though a low one does not prevent it. In temperate climates the summer months, and particularly August and September, are the season of its greatest activity.

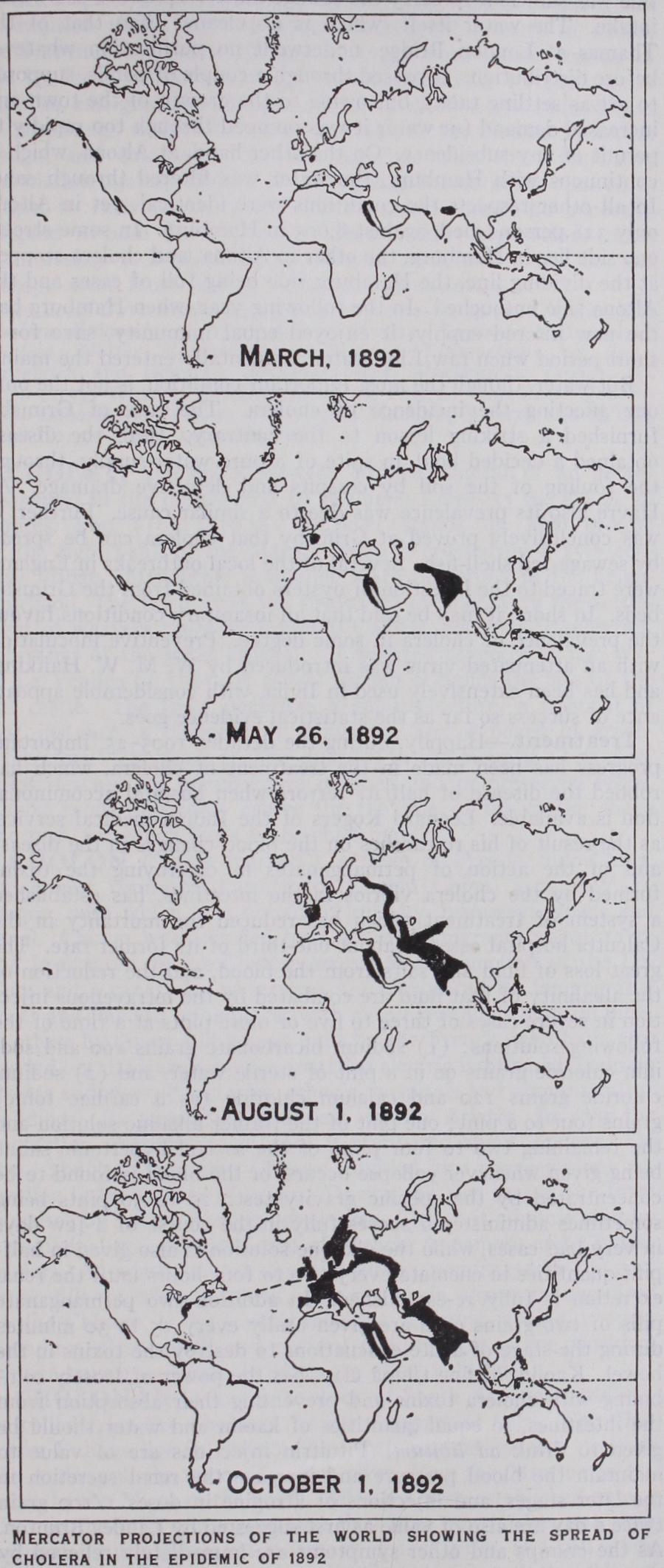

Cholera spreads westwards from India by two routes—(1) by sea to the shores of the Red sea, Egypt and the Mediterranean; and (2) by land to northern India and Afghanistan, thence to Persia and central Asia, and so to Russia. In the great invasions of Europe during the 19th century it sometimes followed one route and sometimes the other. An Indian epidemic of 1817 reached Europe by way of Persia and Russia in 183o and extended to America. Another of 1841 followed the same track and reached Europe and America in 1847. A third took place in the East in 185o and entered Europe in 1853 ; this epidemic was specially severe throughout North and South America. Other epidemics visiting Europe occurred in 1866, 1869-74, 1883-87 ; these trav elled by way of the Mediterranean. The epidemic of 1892-95 re verted to the overland route and travelled with unprecedented rapidity. Within less than five months it travelled from the North West provinces of India to St. Petersburg (Leningrad) and prob ably to Hamburg, and thence in a few days to England and the United States. During the period of 1910-25 cholera continued to be widely prevalent in India, and the recorded mortality exceeded 500,000 in both 1918 and 1919, when the disease was also epidemic in China, but, with the exception of moderate prevalence in eastern and southern Europe, including Italy in 191r, there has been little spread to Europe. Bengal maintains its unenviable reputation as the home of cholera.

Prevention.

The great invasion of 1892-95 was fruitful in lessons for the prevention of cholera. It proved that the one real and sufficient protection lies in a standing condition of good sanitation backed by an efficient and vigilant sanitary administra tion. The experience of Great Britain where the deaths per 10,000 living were less than o-05 was a remarkable piece of evi dence, but that of Berlin was perhaps even more striking, for Berlin lay in the centre of four fires, in direct and frequent corn munication with Hamburg, Russia, France and Austria, and with out the advantage of a sea frontier. Cholera was repeatedly brought into Berlin, but never obtained a footing, and its suc cessful repression was accomplished without any irksome inter ference with traffic or the ordinary business of life. The general success of Great Britain and Germany in keeping cholera in check by ordinary sanitary means completed the conversion of all enlightened nations to the policy laid down so far back as 1865 by Sir John Simon, and advocated by Great Britain at a series of international congresses—the policy of abandoning quar antine, which Great Britain did in 1873, and trusting to sanitary measures with medical inspection of persons arriving from in fected places. This principle was formally adopted at the inter national conference held at Dresden in 1893, at which a con vention was signed by the delegates of Germany, Austria, Belgium, France, Great Britain, Italy, Russia, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Montenegro and the Netherlands. Under this instrument the practice is broadly as follows, though the procedure varies a good deal in different countries : Ships arriving from infected ports are inspected, and if healthy are not detained, but bilge-water and drinking-water are evacuated, and persons landing may be placed under medical supervision without detention; infected ships are detained only for purposes of disinfection; persons suffering from cholera are removed to hospital; other persons landing from an infected ship are placed under medical observation, which may mean detention for five days from the last case; or, as in Great Britain, supervision in their own homes, for which purpose they give their names and places of destination before landing. All goods are freed from restriction, except rags and articles believed to be contaminated by cholera matters. By land, pas sengers from infected places are similarly inspected at the frontiers and their luggage "disinfected," only those found suffer ing from cholera can be detained. Each nation is pledged to notify the others of the existence within its own borders of a "focus" of cholera. The precise interpretation of the term is left to each government, and is treated in a rather elastic fashion by some, but it is generally understood to imply the occurrence of non-imported cases in such a manner as to point to the local pres ence of infection. The question of guarding Europe generally from the danger of diffusion by pilgrims through the Red sea was settled at another conference held in Paris in 1894. The provisions agreed on included the inspection of pilgrims at ports of departure, detention of infected or suspected persons, and supervision of pilgrim ships and of pilgrims proceeding overland to Mecca.The substitution of the procedure above described for the old measures of quarantine and other still more drastic inter ferences with traffic presupposes the existence of a sanitary service and fairly good sanitary conditions if cholera is to be effectually prevented. No doubt if sanitation were perfect in any place or country, cholera, along with many other diseases, might there be ignored, but sanitation is not perfect anywhere, and therefore it requires to be supplemented by a system of notification with prompt segregation of the sick and destruction of infective ma terial. Of general sanitary conditions the most important is unquestionably the water-supply. The classical example is Hamburg. The water-supply is obtained from the Elbe, which became infected by some means not ascertained. The drainage from the town also runs into the river, and the movement of the tide was sufficient to carry the sewage matter up above the water intake. The water itself, which is no cleaner than that of the Thames at London Bridge, underwent no purification whatever before distribution. It passed through a couple of ponds, supposed to act as settling tanks, but owing to the growth of the town and increased demand for water it was pumped through too rapidly to permit of any subsidence. On the other hand, at Altona, which is continuous with Hamburg, the water was filtered through sand. In all other respects the conditions were identical, yet in Altona only 328 persons died, against 8,6o5 in Hamburg. In some streets one side lies in Hamburg, the other in Altona, and cholera stopped at the dividing line, the Hamburg side being full of cases and the Altona side untouched. In the following year, when Hamburg had the new filtered supply, it enjoyed equal immunity, save for a short period when raw Elbe water accidentally entered the mains.

But water, though the most important condition, is not the only one affecting the incidence of cholera. The case of Grimsby furnished a striking lesson to the contrary. Here the disease obtained a decided hold, in spite of a pure water-supply, through the fouling of the soil by cesspits and defective drainage. At Havre also its prevalence was due to a similar cause. Further, it was conclusively proved at Grimsby that cholera can be spread by sewage-fed shell-fish. Several of the local outbreaks in England were traced to the ingestion of oysters obtained from the Grimsby beds. In short, it may be said that all insanitary conditions favour the prevalence of cholera in some degree. Preventive inoculation with an attenuated virus was introduced by W. M. W. Haffkine, and has been extensively used in India, with considerable appear ance of success so far as the statistical evidence goes.

Treatment.

Happily, during the decades 1905-25, important progress has been made in the treatment of cholera, which has robbed the disease of half its terrors when hospital accommoda tion is available. Leonard Rogers of the Indian medical service, as the result of his researches on the blood changes in the disease and of the action of permanganates in destroying the toxins formed by the cholera vibrios in the intestines, has established a system of treatment which has reduced the mortality in the Calcutta hospital cases to about one-third of its former rate. The great loss of fluid and salts from the blood, and the reduction o; the alkalinity of that fluid are combated by the intravenous injec tion in severe cases of three to five or more pints at a time of the following solutions: (r) sodium bicarbonate grains 16o and sod ium chloride grains 90 in a pint of sterile water, and (2) sodium chloride grains 120 and calcium chloride (as a cardiac tonic) grains four to a pint ; one pint of the former alkaline solution and the remaining two to four pints of the second hypertonic saline being given whenever collapse occurs, or the blood is found to be concentrated by the specific gravity test; 20 to 3o pints being sometimes administered successfully in the course of a few days in very bad cases, while the alkaline solution is also given in half pint quantities in enemata every two to four hours until the renal excretion is fully re-established. In addition two permanganate pills of two grains each are given orally every 15 to 3o minutes during the stage of acute evacuations to destroy the toxins in the bowel. Kaolin, or fine China clay, has the power of loosely corn bining with cholera toxins and preventing their absorption from the intestines, so equal quantities of kaolin and water should be given to drink ad libitum. Pituitrin injections are of value to maintain the blood pressure and increase the renal secretion in the later stages, and injections of atropine in doses 1/10o grain twice a day are also of value as first suggested by Lauder Brunton. As the cramps and other symptoms are immediately relieved by the saline injections, opium is unnecessary and should never be given in any stage of cholera, as it strongly predisposes to fatal suppression of urine.By these methods the mortality in over 1,000 severe cases in the Calcutta cholera ward over a number of years past has been reduced from 6o% to 20% and equally good results were obtained in China in 1919. In the Bombay and Central Provinces the administration of large quantities of permanganate pills in out breaks in villages remote from hospitals has reduced the death rate one-half to one-third of that in untreated cases in the same epidemics, although the severest types require intravenous salines in addition if life is to be saved. The great paucity of skilled medical men in Indian villages alone prevents greater saving of life by these methods, and prevention, especially by good water supplies and greater sanitary control of cholera-spreading places of pilgrimage within the endemic areas of the disease in Lower Bengal and south-east Madras, together with the compulsory inoculation against cholera of all pilgrims before being allowed to return to their homes from cholera areas, should be generally adopted without further loss of time if this very serious cause of mortality in India is to be reduced, as it well might be, and Europe saved from further pandemics of cholera.