Chronograph

CHRONOGRAPH, an instrument for recording the passage of time ; thus the name is applied to the stop-watch used for tim ing races, etc. Press a key and the index of the dial sets to zero; press again and the index starts to move at normal rate, say one revolution per 6o secs., by steps of one-fifth sec. ; press a third time and the index stops, and the event is "timed" by reading the dial. Attention to the defects of this crude form of chronograph will show the necessity for the refinements described below. In the first place, by setting the start of the event at zero the timing instrument is detached from other clocks and therefore the absolute time of start and finish are lost; secondly, a watch or other time-piece cannot be trusted to move at a standard pace immediately after it is set in motion; thirdly, no means are provided for checking its going ; fourthly, the step-by-step move ment of the hand of a watch limits the precision of the reading to one whole step ; fifthly, the observer must note the beginning of the event and simultaneously start his watch, and note the end, and simultaneously stop it--otherwise he will introduce an error. In some cases the first condition is of no importance; the others are always important.

The faults relating to the clock are met by a double device. An independent, well-made piece of clock-work moves a paper band at an approximately uniform rate ; on this a standard clock, the rate and error of which can be found otherwise (see TIME, MEASUREMENT OF) impresses a mark every second or every two seconds; the "personal" error of the observer is eliminated by making the event itself impress a similar mark, which as a rule will fall between two of the seconds-marks of the clock, so that the event may be timed with any degree of precision by measur ing the distances of its mark from the two adjacent seconds marks. The exactness of the chronograph is limited by the precision with which these requirements can be carried out in practice; this will be best shown by describing some standard forms.

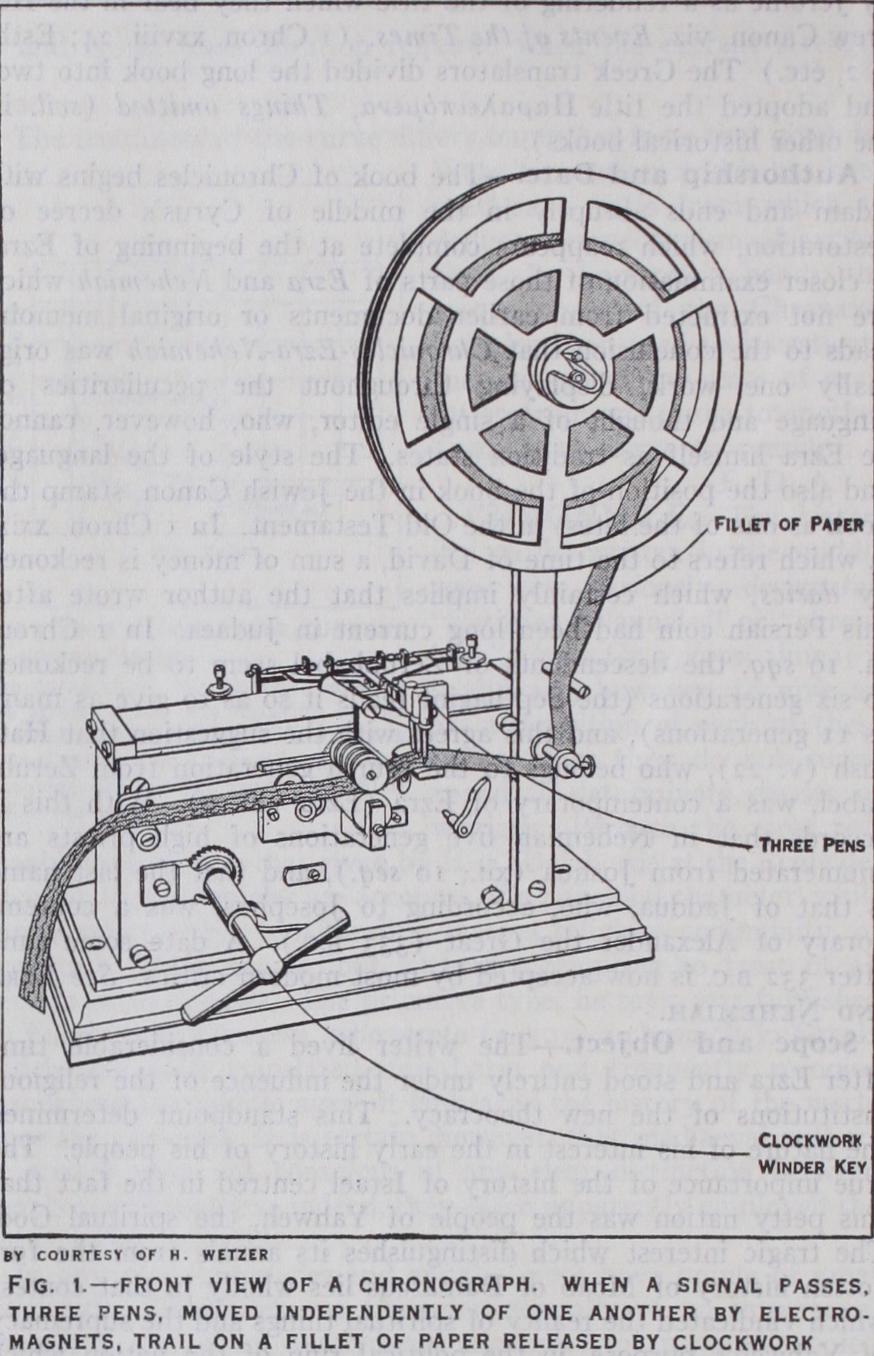

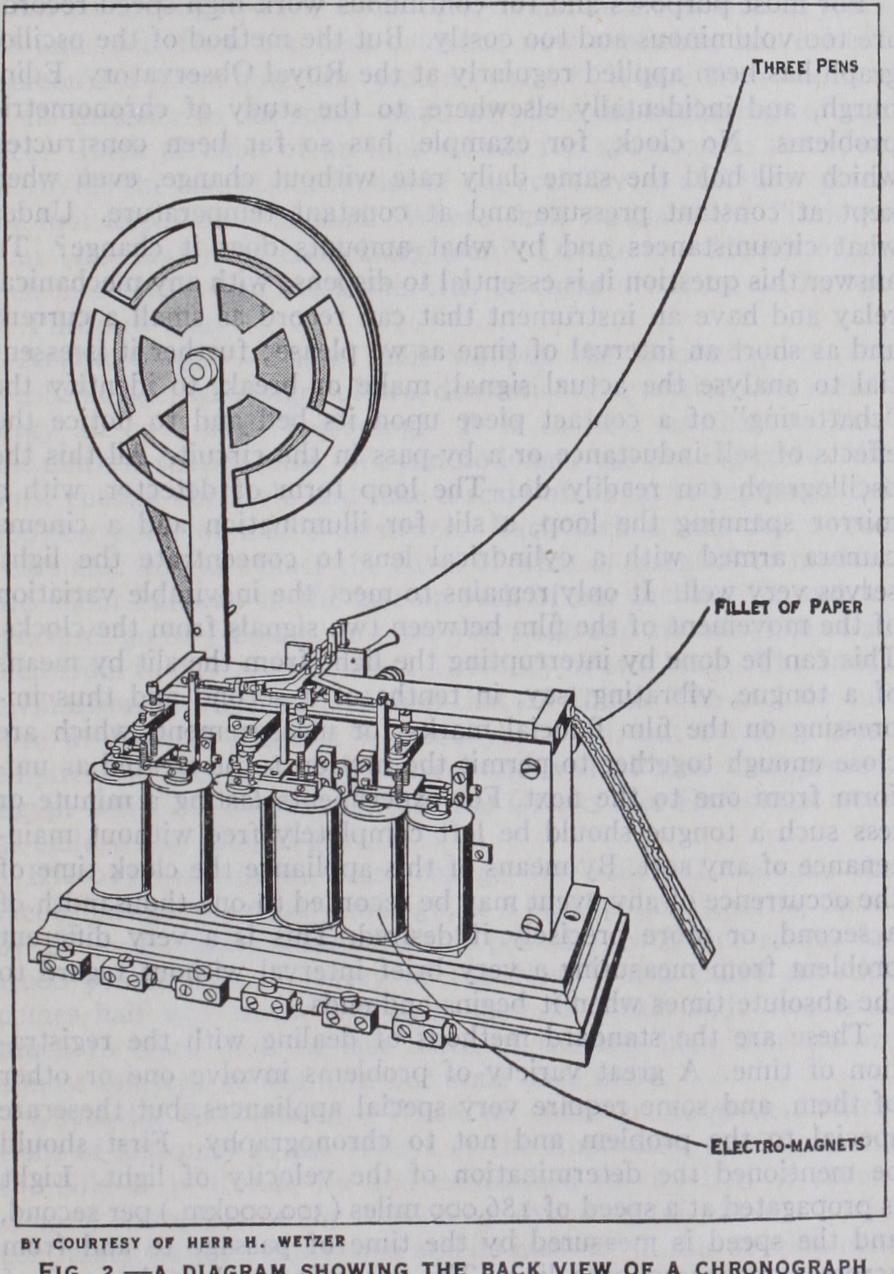

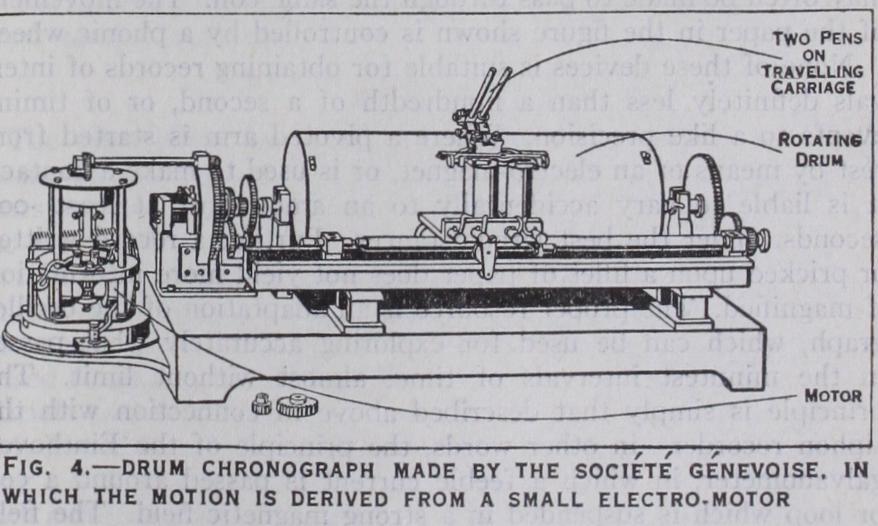

The figures show the front and back view of a three-pen chrono graph by H. Wetzer, Pfronten, Bavaria. A fillet of paper is wound at a regulated and approximately constant speed from a roll over a small bench, above which are three pens in light contact with it, so that when nothing is happening the paper trails beneath them and they leave straight traces. Each pen is carried on an independent arm which is linked to the armature of a pair of electromagnets. If a current passes in one of these magnets, the armature is depressed and the arm moves sharply backwards, indenting the trace in the manner shown in fig. 3 where several traces are given, taken from a six-pen chronograph, corresponding to different settings. Usually the standard clock governs the signals sent to one pair of magnets, say the third trace in this figure, so that the beginning of the indentations would correspond with its seconds. A taper scale, ruled on glass and laid across the paper, permits the time corresponding to any other mark on the paper to be read at sight to, say, one hundredth of a second. If a higher degree of subdivision is wanted, it is advisable to proceed by quite a different method, as described below. In other forms of chronograph the pens are replaced by needle points which prick the paper when the armature descends. The needle is carried in a rocking head so that as the paper moves on, the needle, after pricking the paper, trails until the armature is released again, so as not to retard the movement of the fillet. In other forms again the fillet of paper is replaced by a sheet wound upon a drum, which the clock-work causes to rotate once a minute, while a carriage containing the pens and magnets moves longitudinally beside it. The figure shows a pattern made by the Societe Genevoise. In this pattern the motion is derived from a small electro-motor, and not from weight-driven clock-work.

The chronograph may be arranged so as to yield a print in plain figures of the time recorded. Three wheels, engraved with em bossed figures showing minutes, seconds and hundredths of a second, are driven at a rate which is controlled so as to agree with the standard clock, and a fillet of paper, with an inking ribbon between, passes over them. When a signal passes that has to be recorded, electro-magnets cause three hammers to descend and print upon the paper the figures that are exposed below it. Fig. 3 shows a specimen trace.

In order to make this form of chronograph effective the clock work for driving the type wheels requires rather special attention. The minutes (and seconds) wheels are readily controlled with sufficient accuracy, but the hundredths-of-a-second wheel should not be geared with the others, but should be run by an inde pendent drive, accurately cut, with sensitive appliances for regu lating as required its approximate rate. It is run normally slightly fast, and the control of the standard clock is exercised by a check once a second from the signal of the standard clock. It is desir able also to cause the standard clock itself to record at will its own signals, so that the amount by which the wheel is fast may be noted and applied as an index correction.

The electro-magnets for all these forms require to be fairly powerful, and are usually wound to about 20 ohms. resistance, being worked with batteries of 4 or 6 volts ; the current that runs, o•2amp. or o•3amp., is therefore much greater than that of the signal from the standard clock which will never exceed about so milliamps. A relay must therefore be interposed. It will be noted that the time the relay takes to act, and the time between the commencement of its secondary current and the first movement of the armature, appear as a lag making the record of the chronograph slow on the clock signal. If, however, the error of the clock itself is determined with the same apparatus, the same lag will appear again, and will thus eliminate itself. This supposes the lag to be constant. Experiments show that with the ordinary well-constructed commercial relay, if worked on currents greater than 5 or 6 milliamps, the lag is sensibly constant for the same setting of the relay and should not exceed a few thousandths of a second. See some tests of two Siemens Relays, published by the Commission Geodesique Suisse, i3rd. Sitting, 1927. (Societe-Helvetique des Sciences Naturelles, Neuchatel, 1927.) The part which is due to the electro-magnets of the chron ograph may similarly be kept con stant by attention to the accumu lators that operate them.

As regards the event which has to be timed, any form of contact maker, connected with its occur rence, and in series with a battery and one of the pairs of electro-magnets of the chronograph, will serve. It may be necessary to interpose a relay. The process may be illustrated by astronomical timing, which is one of the most refined forms, and is done as follows. A star in passage across the field of view of a transit instrument is held bisected by a spider thread, the carrier of which for this purpose travels along a screw shaft actuated by a terminal pair of hand drums. Connected with this shaft is a rotating contact maker. At each revolution a contact is made and is recorded on the chronograph, which thus obtains a record of the time when the star passed a number of fiducial positions in the field of view. Manipulation of the drums requires skill, and is sometimes replaced by an automatic drive, but in any case the observer is unaware when he is making a contact and therefore his bias or "personality" cannot enter in that way. Other events would require different arrangements, but the guiding principles would be the same.

It will be noticed that in all these forms of chronograph, except the printing chronograph, the timing of the mark recording the desired event is found by measuring its distance from two time marks, giving as a rule successive seconds. The accuracy there fore depends upon the uniformity of movement of the paper. The clock-work drive, with continuous motion, is liable to fluc tuate more or less. If it does so smoothly, so that it moves the paper at the same rate for several successive seconds, its absolute rate of movement matters little and the measurement may be made at sight, with accuracy up to one-hundredth of a second, by the usual device of a taper scale, engraved on glass, showing seconds of different lengths within the ranges that are likely to occur, and divided into tenths. Sliding the scale across the marked paper, the seconds-marks are fitted to the boundary lines of the scale, and the interpolation of the time of the event in tenths and estimated hundredths is read off. For making this operation accurately the character of the mark on the paper is important. Perhaps the best form in point of accuracy is the circular per foration made by a needle, in place of an ink mark by a pen, but it is trying to the sight unless the illumination is specially arranged, and it is rather easily effaced.

In all cases the signal of the standard clock is so arranged as to indicate the beginning of the minutes, either by omitting a signal or by duplicating it. If it is of importance to feed the paper quite regularly, the device called the phonic wheel may be employed. Clock-work for the drive is replaced by a small electric-motor, which is driven synchronously with a maintained tuning-fork. A fork of 5o periods per second is found suitable. The system gets rid of substantial fluctuations in the feed, but it is far from ideal, for a tuning-fork maintained in the usual way by means of a small electro-magnet excited by a contact made at the extremity of its excursion cannot be relied upon to keep closely a set period as when free.

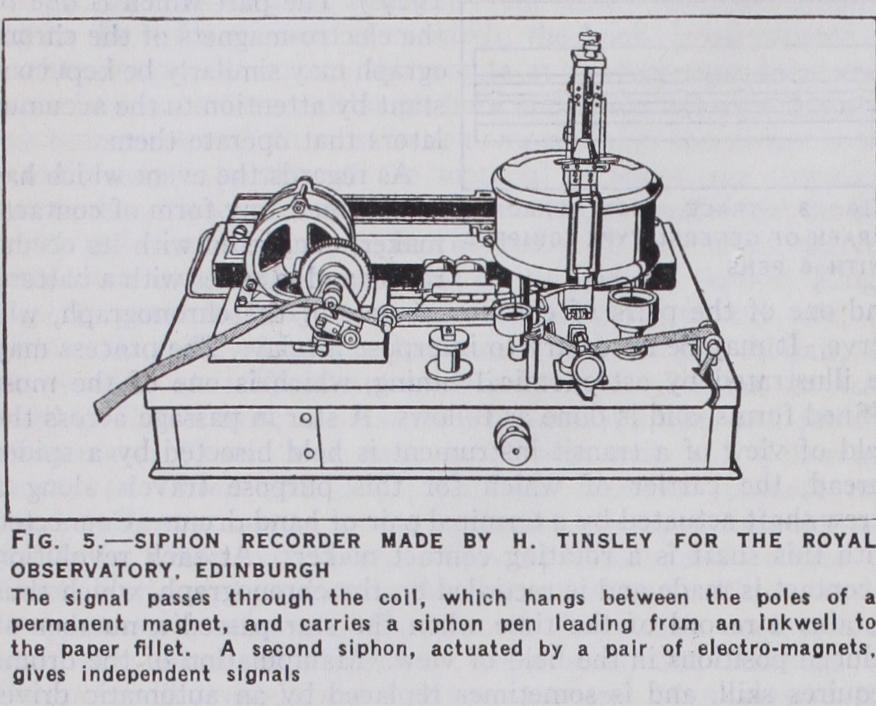

The introduction of relays in the system, in order to replace the weak signal from the standard clock, or that given by the event to be recorded, may be avoided by using the siphon recorder. The illustration shows a recorder manufactured by H. Tinsley and Co. Between the poles of a strong permanent magnet a coil is suspended through which the weak signal current is made to pass. When a current passes, the coil is deflected. Attached to the coil is the "siphon," which usually consists of a very fine glass tube, bent to an appropriate shape and conveying ink from a well to the fillet of paper which travels at a lower level. A very small current may be made to record directly on this apparatus. Both the signals, from the clock and from the events for record, may often be made to pass through the same coil. The movement of the paper in the figure shown is controlled by a phonic wheel. None of these devices is suitable for obtaining records of inter vals definitely less than a hundredth of a second, or of timing events to a like precision. Where a pivoted arm is started from rest by means of an electro-magnet, or is used to make a contact, it is liable to vary accidentally to an amount of at least .003 seconds, under the best circumstances. Further a record written or pricked upon a fillet of paper does not yield more information if magnified. The proper resource is an adaptation of the oscillo graph, which can be used for exploring accurately what passes in the minutest intervals of time, almost without limit. The principle is simply that described above in connection with the siphon recorder—in other words, the principle of the Einthoven galvanometer, in which a feeble current is passed around a coil or loop which is suspended in a strong magnetic field. The field deflects the coil when a current passes. By suspending the coil with an appropriate reaction to return to its normal position, and by changing the magnetic field, the deflection may be made of any suitable amount, and to take place in a given period of time which may be made very short. With air damping the motion is perfectly dead beat. Further, whether the signal cur rent is constant or not, the interval of time between its onset and the final set of the coil is strictly constant, so that the lag introduced is the same in every case, and the variation of the actuating current is recorded without distortion. A small light mirror mounted on the coil or loop shows the deflection by reflecting a fixed spot of light, or alternatively the current may pass along a single wire or thread and the deflection of this thread by the magnetic field may be projected optically. The pro jection is recorded photographically. Any degree of rapidity of change may be met by suitable movement of the recording film. For speeds that are not too great, and for prolonged records, a cinema camera with its roll of film is driven by an electric motor. For great speeds a plate may be allowed to fall between guides past the exposure window. Feebleness of signal current is met by intensifying the magnetic field, and again the photographic record may be magnified in a microscope. By this device the details of tht oscillating discharge of a condenser may be made evident, or, on the other hand, the feeblest physiological currents may be recorded. Clearly it only requires adaptation to the problem to make it an instrument practically perfect for pure time recording.

It has thus been applied in "sound-ranging" in artillery, which consists in the location of the position of a gun by noting the difference of time of arrival of the sound at three known points. A special form of detector permits the use of very small currents; the oscillograph or galvanometer is used in the form where the signals for record, whether event or clock, pass through single threads, the movements of which are projected side by side and photographed on a moving strip. In this way the true times of arrival of the sound of all the guns of a battery, side by side and fired by intention as nearly as possible at the same moment, are sorted out from one another with perfect distinctness.

For most purposes and for continuous work high speed records are too voluminous and too costly. But the method of the oscillo graph has been applied regularly at the Royal Observatory, Edin burgh, and incidentally elsewhere, to the study of chronometric problems. No clock, for example, has so far been constructed which will hold the same daily rate without change, even when kept at constant pressure and at constant temperature. Under what circumstances and by what amounts does it change? To answer this question it is essential to dispense with any mechanical relay and have an instrument that can record as small a current and as short an interval of time as we please; further it is essen tial to analyse the actual signal, make or break, to identify the "chattering" of a contact piece upon its bed and to notice the effects of self-inductance or a by-pass in the circuit. All this the oscillograph can readily do. The loop form of detector, with a mirror spanning the loop, a slit for illumination and a cinema camera armed with a cylindrical lens to concentrate the light, serves very well. It only remains to meet the inevitable variation of the movement of the film between two signals from the clocks. This can be done by interrupting the light from the slit by means of a tongue, vibrating, say, in tenths of a second and thus im pressing on the film fiducial marks for measurement, which are close enough together to permit the motion to be treated as uni form from one to the next. For experiments lasting a minute or less such a tongue should be left completely free without main tenance of any sort. By means of this appliance the clock time of the occurrence of any event may be recorded to one-thousandth of a second, or more precisely if desired. This is a very different problem from measuring a very brief interval without regard to the absolute times when it begins and ends.

These are the standard methods of dealing with the registra tion of time. A great variety of problems involve one or other of them, and some require very special appliances, but these are special to the problem and not to chronography. First should be mentioned the determination of the velocity of light. Light is propagated at a speed of 186,00o miles (300,o00km.) per second, and the speed is measured by the time of passage to and from across a measured base line. The exceedingly short interval of time involved is not recorded but is merely determined in terms of the period of a standardized tuning-fork. (See the articles "Velocity of Light" and "Measurement of Time" by A. A. Michel son, in the Astrophysical Journal of the University of Chicago, Vol. 65 [1927] p. I.) Problems of the flight of projectiles resolve themselves into the question of causing the projectile to make suitable signals at definite points, which is most simply done by making it sever wires conveying electric currents. If the question is merely to ascertain the speed of a small projectile, the chrono graph is not involved, as the speed may be ascertained by firing the projectile into a massive wooden block mounted as a pen dulum, and then measuring the momentum conveyed to the block by noting the angle to which it swings. (R. A. S.)