Civil List

CIVIL LIST, the English term for the account in which are contained all the expenses immediately applicable to the support of the British sovereign's household and the honour and dignity of the crown. An annual sum is settled by the British parliament at the beginning of the reign on the sovereign, and is charged on the consolidated fund. But it is only from the reign of William IV. that the sum thus voted has been restricted solely to the personal expenses of the crown. Before his accession many charges properly belonging to the ordinary expenses of govern ment had been placed on the Ci Al List.

William and Mary.

The history of the Civil List dates from the reign of William and Mary. Before the Revolution no dis tinction had been made between the expenses of government in time of peace and the expenses relating to the personal dignity and support of the sovereign. The ordinary revenues derived from the hereditary revenues of the crown, and from certain taxes voted for life to the king at the beginning of each reign, were supposed to provide for the support of the sovereign's dignity and the civil government, as well as for the public defence in time of peace. Any saving made by the king in the expenditure touching the government of the country or its defence would go to swell his privy purse. But with the Revolution a step forward was made towards the establishment of the principle that the expenses relat ing to the support of the crown should be separated from the ordinary expenses of the State. The evils of the old system under which no appropriation was made of the ordinary revenue granted to the crown for life had been made manifest in the reigns of Charles II. and James II. ; it was their control of these large revenues that made them so independent of parliament. More over, while the civil government and the defences suffered, the king could use these revenues as he liked.The parliament of William and Mary voted in 1689 an annual sum of £600,000 for the charge of the civil government. This was a mere resolution without statutory effect. In 1697 the first Civil List act was passed. Certain revenues (the hereditary reve nues of the crown and a part of the excise duties), estimated to yield £700,000, were assigned to the king to defray the expenses of the civil service and the payment of pensions, as well as the cost of the royal household and the king's own personal expenses or "Privy Purse." The Civil List meant practically all the ex penses of government except the debt charge and defence. If the yield of the assigned revenues exceeded £700,000 the surplus was to be disposed of by parliament. This restriction was removed by an Act of 1700. In the reign of Anne the Civil List consisted of the same assigned revenues (subject to certain deductions). The yield fell short of the estimate of £ 700,000, and at the end of the reign a debt of £500,0oo was met from the Exchequer.

The Hanoverians.

For George I. additional revenues were assigned, and it was enacted in effect that the Civil List should become independent of the yield of the assigned revenues, and should be a fixed sum of £700,000 a year. Any surplus was to be surrendered, and any deficiency would be made good. But this was found insufficient and parliament from time to time made additional grants from the Exchequer to pay off debts amounting in the aggregate to £1,300,000. In the reign of George II. there was again a change of system. The Civil List was composed of the assigned revenues, together with certain fixed grants, and a minimum yield of 1800,000 was guaranteed by parliament. Any surplus yield over £800,000 was retained by the king. On the accession of George III. the system of a fixed Civil List was reverted to. The assigned revenues were no longer paid to the crown but to the aggregate fund as part of the revenues of the Exchequer, and the fixed allowance of £800,000 was paid out of the aggregate fund to the king (subject to certain annuities pay able to members of the royal family).During the reign of George III., the Civil List played an impor tant part in the king's effort to establish the royal ascendancy. The "king's friends," his supporters in parliament, were lavishly rewarded with places, pensions and even bribes. Upon the expendi ture of the Civil List there was no independent check. So long as the total was not exceeded, the king, with the co-operation of complaisant ministers, was free to spend it as he pleased. As it turned out, despite stringent economies in the cost of the house hold, excesses were incurred. But parliament, already corrupted, was persuaded to provide extra funds to pay off the debts in 1769 and again £618,340 in 1777). Proposals for enquiry, supported by Chatham, were resisted and negatived.

Burke had already attacked the extravagance and corruption of the Civil List and in 1780 he introduced bills embodying his scheme of economic reform. The scrieme could not be passed against Lord North's government, but in 1782 the Rockingham ministry passed a Civil List act which abolished many useless offices, imposed restraints on the issue of secret service money, stopped secret pensions payable during the king's pleasure, and provided for a more effectual supervision of the royal expenditure.

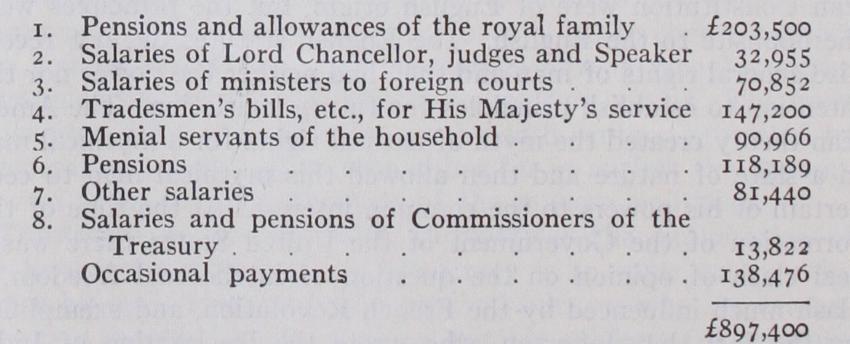

The Civil List was divided into classes, and the requirements of each were estimated as follows by a committee of 1786:— Substantially classes 1, 4 and 5, amounting to £431,666, repre sented what is now covered by the Civil List and the annuities to the royal family, though a few items in class 4 belonged to the cost of government, and a few in class 6 and among the occasional items would now come under the Civil List. These estimates for the several classes were not binding, and they were in fact soon exceeded. Indebtedness accumulated and had from time to time to be paid off (£2,266,000 in all between 1782 and 1820). The amount of the Civil List itself was augmented, and in 1816 it was fixed at 4083,727. Meanwhile the principal pro vision for the civil government had come to be made outside the Civil List. Annual votes of parliament for what were called miscellaneous services had been between £200,000 and £300,000 in the earlier years of George III.'s reign, and had been mainly casual and non-recurrent. By 1820 they amounted regularly to about £2,000,000 a year. On the accession of William IV. in 183o, the Civil List was finally freed from all charges for the govern ment service as distinguished from the court and royal family. The charges for judicial and diplomatic salaries and for the Board of Treasury were transferred to the Exchequer. The ex penses left were covered by a Civil List of £510,00o. This included a sum of £75,000 for pensions.

Civil List Pensions.—The pensions were excluded from Queen Victoria's Civil List, which was reduced to f385,000 (sepa rate provision of £ I oo,000 being made for Queen Adelaide, who had had a privy purse of £50,000 during her husband's reign).

A new system of "Civil List Pensions" was set on foot. The queen might, on the advice of her ministers, grant pensions up to a limit of £1,200 granted in any one year, in accordance with a resolution of the House of Commons of Feb. 18, 1834, "to such persons as have just claims on the royal beneficence or who, by their personal services to the crown, by the performance of duties to the public, or by their useful discoveries in science and attainments in literature and art, have merited the gracious con sideration of the sovereign and the gratitude of their country." The pensions in course of payment at any one time usually amount to about £24,000. The list of pensions must be laid before parliament every year.

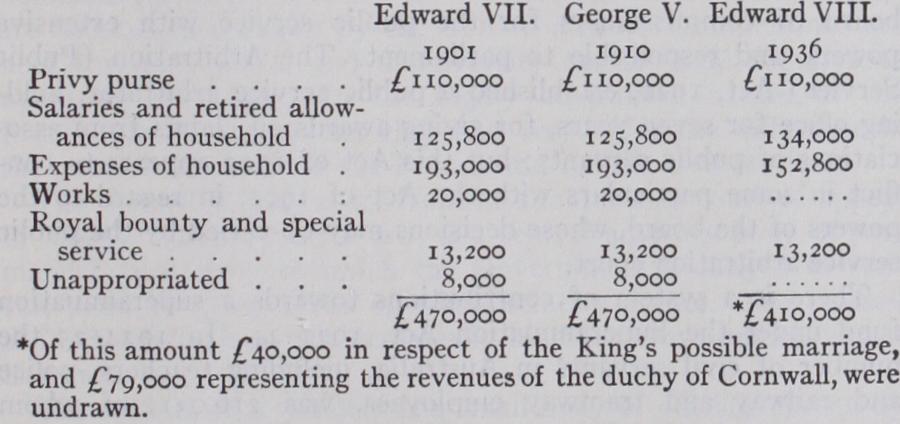

Queen Victoria to Edward VIII.—Queen Victoria's Civil List amounted to £385,000. The sums granted since 1901 are as follows:— The addition of £5o,000 to the privy purse for King Edward VII. and for King George V. was to provide in each case for the Queen Consort. The new class for works introduced in 1901 was partly composed, of an item previously included under ex penses, and partly of expenditure previously voted by parliament. The reduction in salaries was due to the abolition of the post of Master of the Buckhounds, and some other reductions of estab lishments and emoluments. The allocation among classes is not absolutely binding, in that savings on one class can be applied to meet excesses on another (or added to the privy purse) with the consent of the Treasury. Class v. (works) is an exception, savings upon it being accumulated for future years.

No change was made either in the total or the details on the accession of King George V. in 191o, but there was a slight change of practice introduced. In 1842 Queen Victoria, though under no legal or constitutional obligation to pay taxes of any kind, undertook voluntarily to pay income tax. King Edward con tinued the voluntary payment. King George V. agreed with the government of the day that it should be discontinued, but in exchange placed on the Civil List the cost of State visits of foreign royalties previously defrayed from public funds. In 1916 the King made a voluntary gift of £ioo,000 towards the cost of the World War. In addition to the Civil List the King receives the revenues of the duchy of Lancaster. The revenues of the duchy of Cornwall belong to the prince of Wales as duke of Cornwall, but in the absence of a prince of Wales, as in the reign of Edward VIII., they revert to the crown.

At the beginning of a new reign it is the practice for the House of Commons to appoint a select committee to make recommenda tions for the Civil List and the annuities to the royal family. Constitutionally the settlement is still regarded as in the nature of a bargain for the surrender of the hereditary revenues to parlia ment (see preamble of the Civil List act 1910). The accounts of the Civil List are passed by an auditor appointed by the Treasury under the Civil List Audit act, 1816. He is always a high officer of the permanent staff of the Treasury, sometimes the Permanent Secretary himself. (R. G. H.)