Climate and Climatology

CLIMATE AND CLIMATOLOGY. The word clima (from Gr. KXiveLv, to lean or incline) was used by the Greeks for the supposed slope of the earth towards the pole, or for the incli nation of the earth's axis. A change of clima then meant a change of latitude. The latter was gradually seen to mean a change in atmospheric conditions as well as in length of day, and clima thus came to have its present meaning. "Climate" is the average con dition of the atmosphere. "Weather" denotes a single occurrence, or event, in the series of conditions which make up climate. The climate of a place is thus in a sense its average weather. Clima tology is the study or science of climates ; it is a branch of the science of meteorology (q.v.).

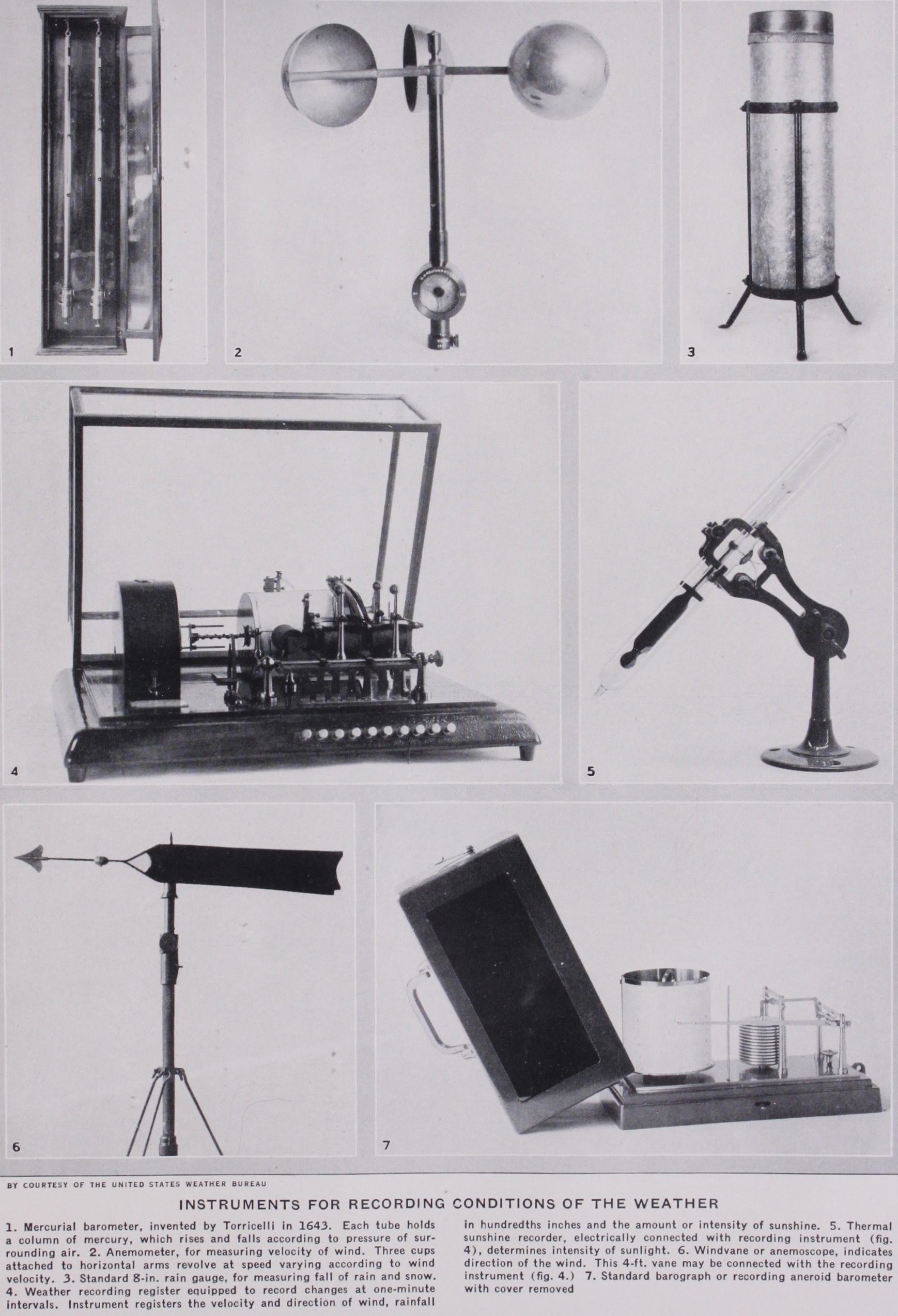

Climatic Elements and Their Treatment.—Climatology has to deal with the atmospheric conditions which affect human life, viz., temperature (including radiation) ; moisture (including humidity, precipitation and cloudiness) ; wind (including storms) and evaporation. Climate deals first with average conditions, but a satisfactory presentation of a climate must take account, also, of regular and irregular daily, monthly and annual changes, and of local departures, mean and extreme, from the average conditions. The mean minimum and maximum temperatures or rainfalls of a month or a season are important `data. Further, a determination of the frequency of occurrence of a given condition, or of certain values of that condition, is important, for periods of a day, month or year, as for example the frequency of winds according to direc tion or velocity; or of different amounts of cloudiness. The probability of occurrence of any condition, as of rain in a certain month, is also a useful thing to know.

Solar Climate.

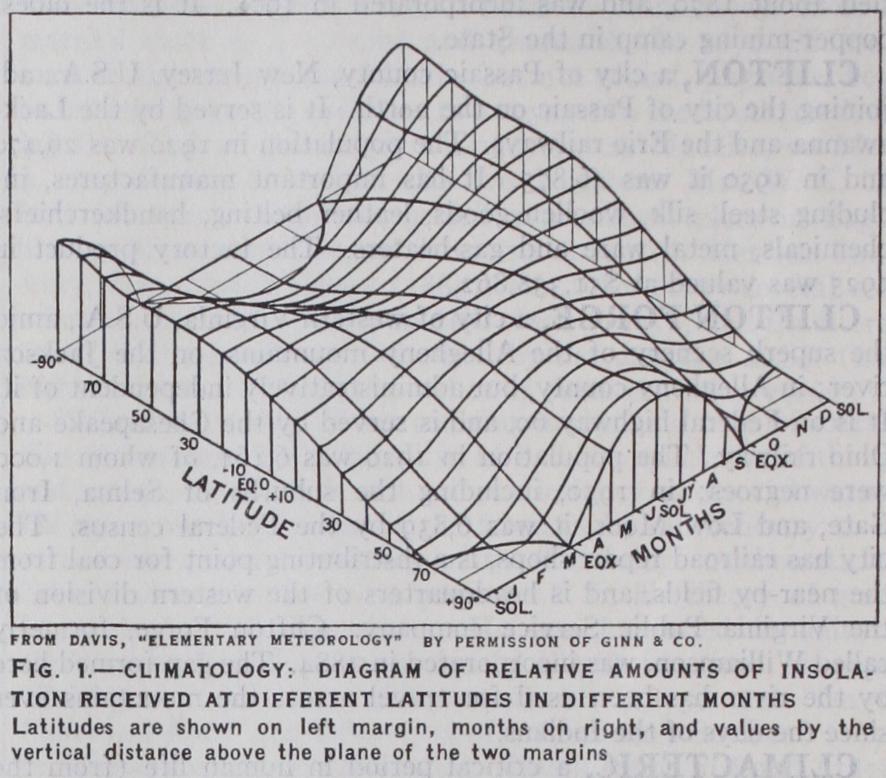

Climate, in so far as it is controlled solely by the amount of solar radiation which any place receives by reason of its latitude, is called solar climate. Solar climate alone would prevail if the earth had a homogeneous land surface, and if there were no atmosphere. The relative amounts of insolation received at different latitudes and at different times at the upper limit of the earth's atmosphere, i.e., without the effect of absorption by the atmosphere, are shown in fig. I after Davis. The latitudes are given at the left margin and the time of year at the right margin. The values of insolation are shown by the vertical distance above the plane of the two margins. At the Equator, where the day is always 12 hours long, there are two maxima of insolation at the equinoxes, when the sun is vertical at noon, and two minima at the solstices when the sun is farthest off the Equator. The values do not vary much through the year because the sun is never very far from the zenith, and day and night are always equal. As latitude increases, the angle of insolation becomes more oblique and the intensity decreases, but at the same time the length of day rapidly increases during the summer, and towards the pole of the hemisphere which is having its summer, the gain in insolation from the latter cause more than compensates for the loss by the former. The double period of insolation above noted for the equator prevails as far as about lat. 12° N. and S. ; at lat. 15° the two maxima have united in one, and the same is true of the min ima. At the pole there is one maximum at the summer solstice, and no insolation at all while the sun is below the horizon. On June 21 the Equator has a day I 2hr. long, but the sun does not reach the zenith, and the amount of insolation is therefore less than at the equinox. On the northern tropic, however, the sun is vertical at noon, and the day is more than r 2hr. long. Hence the amount of insolation received at this latitude is greater than that received at the equinox at the Equator. From the tropic to the pole the sun stands lower and lower at noon, and the value of insolation would steadily decrease with latitude if it were not for the increase in the length of day. Going polewards from the north ern tropic on June 21, the value of insolation increases for a time, because although the sun is lower, the number of hours during which it shines is greater. A maximum value is reached at about lat. 431°N. The decreasing altitude of the sun then more than compensates for the increasing length of day, and the value of insolation diminishes, a secondary minimum being reached at about lat. 62°. Then the rapidly increasing length of day towards the pole again brings about an increase in the value of insolation, until a maximum is reached at the pole which is greater than the value received at the Equator at any time.

On June 21 there are therefore two maxima of insolation, one at lat. 431° and one at the north pole. From lat. N., insolation decreases to zero on the Antarctic circle, for sunshine falls more and more obliquely, and the day becomes shorter and shorter. Beyond lat. 661° S. the night lasts 24 hours. On Dec. 21 the con ditions in southern latitudes are similar to those in the northern hemisphere on June 21, but the southern latitudes have higher values of insolation because the earth is then nearer the sun. At the equinox the days are equal everywhere, but the noon sun is lower and lower with increasing latitude in both hemispheres until the rays are tangent to the earth's surface at the poles (except for the effect of refraction). Therefore, the values of insolation diminish from a maximum at the Equator to a minimum at both poles.

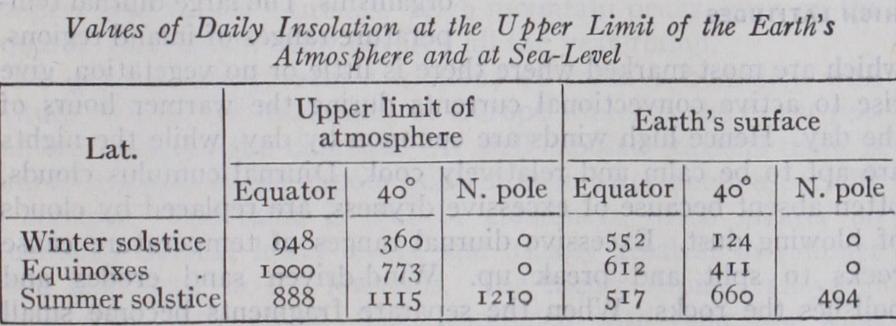

The earth's atmosphere weakens the sun's rays. The more nearly vertical the sun, the less the thickness of atmosphere traversed by the rays. The values of insolation at the earth's surface vary with the condition of the air as to dust, clouds, water vapour, etc. As a rule, even when the sky is clear, about one-half of the solar radiation is lost during the day by atmos pheric absorption. The great weakening of insolation at the pole, where the sun is very low, is especially noticeable. The following table (af ter Angot) shows the effect of the earth's atmosphere (coefficient of transmission 0.7) upon the value of insolation received at sea-level.

These values are relative only ; during the present century the Astrophysical Observatory of the Smithsonian Institution of Washington, under the direction of C. G. Abbot, has estimated the actual intensity of the sun's radiation at the limit of the earth's atmosphere as 1.95 gramme-calories per sq.cm. per minute. (See RADIATION, THEORY OF.) This value is termed the "solar constant," though it varies within about five per cent. on either side of this mean value. The value of r,000 on the above scale represents about 94o gramme-calories per sq.cm. of horizontal surface.

Physical Climate.

The distribution of insolation explains many of the large facts of temperature distribution ; for example, the decrease of temperature from Equator to poles ; the double maximum of temperature on and near the Equator ; the increas ing seasonal contrasts with increasing latitude, etc. But the regular distribution of solar climate between Equator and poles which would exist on a homogeneous earth, whereby similar con ditions prevail along each latitude circle, is very much modified by the unequal distribution of land and water ; by difference of altitude; by air and ocean currents, by varying conditions of cloudiness and so on. The uniform arrangement of solar climatic belts arranged latitudinally is interfered with, and what is known as physical climate results. According to the dominant control we have solar, continental and marine, and mountain climates. In the first-named, latitude is the essential ; in the second and third, the influence of land or water ; in the fourth, the effect of altitude.

Classification of the Zones by Latitude Circles.

The five familiar zones are the so-called torrid, the two temperate and the two frigid zones. The torrid zone is limited north and south by the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, the Equator dividing the zone into two equal parts. The temperate zones are limited towards the Equator by the Tropics, and towards the poles by the Arctic and Antarctic circles. The two polar zones are caps covering both polar regions, and bounded on the side towards the Equator by the Arctic and Antarctic circles. These are really zones of solar climate. The tropical zone has the greatest annual amount and the least annual variation of insolation. Its annual range of temperature is very slight. Beyond the Tropics the contrasts between the seasons rapidly become more marked. The polar zones have the greatest variation in insolation between summer and winter. They also have the minimum amount of insolation for the whole year; their summer is so short and cool that the heat is insufficient for most forms of vegetation, especially for trees. The temperate zones are intermediate between the tropical and the polar in the matter of annual amount and of annual variation of insolation. Temperate conditions do not characterize these zones as a whole. They are rather the seasonal belts of the world.

Temperature Zones.

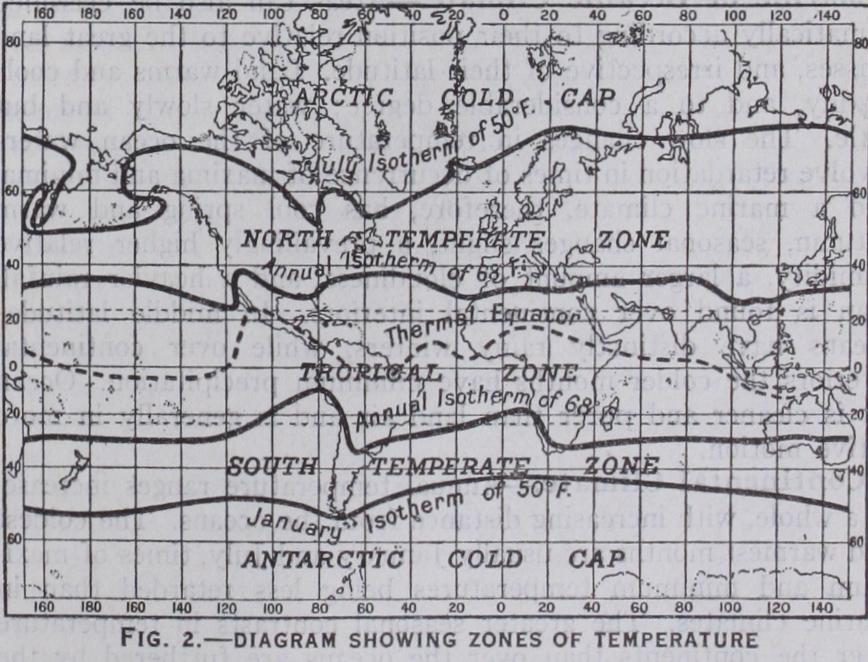

The astronomical classification of the ' zones serves very well for purposes of simple description, but a glance at any isothermal chart shows that the isotherms do not coincide with the latitude lines. In fact, in the higher latitudes, the former sometimes follow the meridians more closely than they do the parallels of latitude. Hence it has been suggested that the zones be limited by isotherms rather than by parallels of latitude, and that a closer approach be thus made to the actual conditions of climate. Supanl has suggested limiting the hot belt, which corresponds to, but is slightly greater than, the old torrid zone, by the two mean annual isotherms of 68° F—an isothermal line which approximately coincides with the polar limits of the trade-winds and with the natural distribution of palms. The limits of these zones, according to the most recent information, are shown in fig. a. The hot belt widens somewhat over the continents, chiefly because there is a tendency towards an equalization of the temperature between Equator and poles in the oceans, while the stable lands acquire a temperature suitable to their own latitude. Furthermore, the unsymmetrical distribution of land in low lati tudes of northern and southern hemispheres makes the hot belt Supan, Grundziige der physischen Erdkunde (Leipzig, 1896), 88-89. Also Atlas of Meteorology, Pl. i.

extend farther north than south of the Equator. The polar limits of the temperate zones are fixed by the isotherm of 5o° F for the warmest month. Summer heat is more important for vegetation than winter cold, and where the warmest month has a temperature below 50° F cereals and forest trees do not grow. The two polar caps are not symmetrical. Extended land masses in high northern latitudes carry the temperature of 5o° F in the warmest month farther poleward there than is the case in high southern latitudes occupied by the oceans which warm less easily and are constantly in motion. Hence the southern cold cap, with equatorial limits at about lat. 5o° S., is much larger than the northern polar cap. The northern temperate belt in which the great land areas lie is much broader than the southern belt, especially over the conti nents. These temperature zones emphasize the natural conditions of climate more than is the case in any subdivision by latitude circles, and they bear a fairly close resemblance to the old zonal classification of the Greeks.

Classification of Climates.

The best and most logical form of classification is one which takes account of all the different climatic elements. Such a scheme has been prepared by W. Koppen (Die Klimate der Erde, Berlin and Leipzig 1923) and assigns almost as much importance to rainfall as to temperature. Since the rainfall depends largely on prevailing winds, this classi fication also takes account of the zones of wind. Eight main zones are distinguished and divided and subdivided into a number of climatic provinces and smaller areas. Each subdivision is dis tinguished by a formula comprised of the main division followed by the initial letters of its characteristics: e.g., the climate of Swakopmund is described as BWkn, which means a sub-tropical (B) desert (Waste) climate with a cold (kalt) winter and fre quent fog (Nebel) . The eight zones are : A tropical rain zone with the coldest month usually above 64° F and rainfall above the limit of dryness (which varies according to the temperature and the seasonal distribution of rain) ; two zones of dry (steppe and desert) climate; two zones of warm temperate rain climate with the mean temperature of the coldest month between 64° and 27° F. (these include the "Mediterranean" and most of the "monsoon" climatic areal) ; a zone of "boreal" or snow and forest climate (with hot summers and cold winters below 27° F), which requires a large area of land and is consequently missing in the southern hemisphere; and two polar caps of "snow climate" with the mean temperature of the warmest month below 5o° F.

Marine or Oceanic Climate.

Areas can also be classified climatically according to their position relative to the great land masses, and irrespective of their latitude. Land warms and cools readily, and to a considerable degree ; water slowly and but little. The slow changes in temperature of the ocean waters involve retardation in times of occurrence of maxima and minima, and a marine climate, therefore, has cool spring and warm autumn, seasonal changes slight, a prevailingly higher relative humidity, a larger amount of cloudiness, and a heavier rainfall than is found over continental interiors. In middle latitudes oceans have distinctly rainy winters, while over continental interiors the colder months have minimum precipitation. Ocean air is cleaner and purer than land air and is generally in more active motion.

Continental Climate.

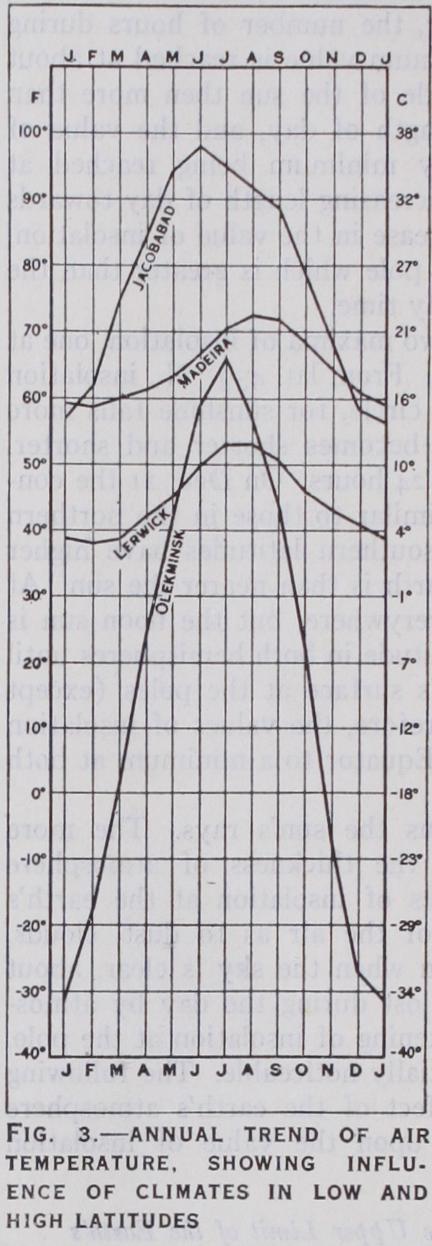

Annual temperature ranges increase, as a whole, with increasing distance from the oceans. The coldest and warmest months are usually January and July, times of maxi mum and minimum temperatures being less retarded than in marine climates. The greater seasonal contrasts in temperature over the continents than over the oceans are furthered by the smaller humidity and cloudiness over the former. Diurnal and annual changes of nearly all elements of climate, irregular as well as regular, are greater over continents than over oceans. Fig. 3 illustrates the annual march of temperature in marine and con tinental climates. Jacobabad in India (J) , and Funchal on the island of Madeira (M) are representative continental and marine stations for a low latitude. Olekminsk in Siberia (01) and Lerwick in the Shetlands (L) are good examples of continental and marine climates of higher latitudes in the northern hemisphere.Owing to distance from chief source of water vapour—the , oceans—air over the larger land areas is drier and dustier than that over the oceans. Yet even in arid continental interiors in summer absolute vapour content is surprisingly large, and in the hottest months percentages of relative humidity may reach 2o% or 3o%; e.g., in July, Luktschum with an average temperature of 90° and a relative humidity of 31 per cent. has more moisture in the air than Valentia with a temperature of 59° and a relative humidity of 83 per cent. Cloudi ness, as a rule, decreases inland, and with this lower relative hu midity, more abundant sunshine and higher temperature, the evap orating power of a continental climate in summer is much greater than that of the more humid, cloudier and cooler marine climate. Both amount and fre quency of rainfall, as a rule, de crease inland, but conditions are very largely controlled by local topography and prevailing winds. Winds average somewhat lower in velocity, and calms are more fre quent, over continents than over oceans. Seasonal changes of pressure over the former give rise to systems of inflowing and out-flowing, so-called continental, winds, sometimes so well de veloped as to become true mon soons. Extreme temperature changes over continents are the more easily borne because of the dryness of the air; because the minimum temperature of winter occurs when there is little or no wind, and because during the warmer hours of the summer there is the most air-move ment.

Desert Climate.

Desert air is notably free from micro organisms. The large diurnal tem perature ranges of inland regions, which are most marked where there is little or no vegetation, give rise to active convectional currents during the warmer hours of the day. Hence high winds are common by day, while the nights are apt to be calm and relatively cool. Diurnal cumulus clouds, often absent because of excessive dryness, are replaced by clouds of blowing dust. Excessive diurnal ranges of temperature cause rocks to split and break up. Wind-driven sand erodes and polishes the rocks. When the separate fragments become small enough they, in their turn, are transported by the winds and further eroded by friction during their journey. Rivers "wither" away, or end in brackish lakes.

Coast or Littoral Climate.

Between pure marine and pure continental types coasts furnish almost every grade of transition. Prevailing winds are here important controls. When these blow from the ocean, climates are marine in character, but when they are off-shore, a modified continental climate prevails, even up to the immediate sea-coast. The former have smaller range of temperature ; the air is damp, and there is much cloud. All these marine features diminish with increasing distance from the ocean, especially when there are mountain ranges near the coast. In the Tropics, windward coasts are usually well supplied with rainfall, and temperatures are modified by sea breezes. Leeward coasts in the trade-wind belts offer special conditions. Here deserts often reach the sea, as on the western coasts of South America, Africa and Australia. Cold ocean currents, with prevailing winds along-shore rather than on-shore, are here hostile to cloud and rainfall, although the lower air is often damp, and fog is common in these regions.

Monsoon Climate.

Exceptions to the general rule of rainier eastern coasts in trade-wind latitudes are found in monsoon regions, as in India, for example, where the western coast gets much rain from the south-west monsoon. As monsoons often sweep over large districts, not only coast but interior, a separate group of monsoon climates is desirable. In India there are really three seasons—the cool winter, the hot transition, and the wet summer monsoon. Little precipitation occurs in winter, and that chiefly in the northern provinces. The winter monsoon is nor mally off-shore and the summer monsoon on-shore, but exceptional cases are found where the opposite is true, as in north-east Ceylon. In higher latitudes the seasonal changes of the winds, although not truly monsoonal, involve differences in temperature and in other climatic elements. The only well-developed mon soons on the coast of the continents of higher latitudes are those of eastern Asia. These are off-shore during the winter, giving dry, clear and cold weather ; while the on-shore movement in summer gives cool, damp and cloudy weather.

Mountain and Plateau Climate.

Temperature decreases upwards at an average rate of 3° per i,000ft., and for this reason and also because of their obstructive effects, mountains are im portant climatic factors. Mountains as contrasted with lowlands are characterized by decrease in pressure, temperature and absolute humidity; increased intensity of insolation and radiation; usually greater frequency of, and up to a certain altitude more, precipitation. The highest habitations are about i 6,000f t. above sea-level, at which altitude pressure has about half its sea-level value. The intensity of the sun's rays is very great in the cleaner, drier and thinner mountain air. Vertical decrease of temperature is especially rapid during warmer months and hours; mountains are then cooler than lowlands. The inversions of temperature characteristic of the colder months, and of the night, give mountains the advantage of a higher temperature then. At such times cold air flows down the mountain sides and collects in the valleys, being replaced by warmer air aloft. Hence diurnal and annual ranges of temperature on the mountain tops of middle and higher latitudes are lessened and the climate in this respect resembles the marine. High enclosed valleys often show con tinental conditions of large temperature range and such valleys in Europe open to the north-east form local "Siberias." Plateaus, as compared with mountains at the same altitude, have relatively higher temperatures and larger temperature ranges. Altitude tempers heat in low latitudes. High mountain peaks, even on the Equator, can remain snow-covered all the year round.No general law governs variations of relative humidity with altitude, but on the mountains of Europe winter is the driest sea son, and summer the dampest. At well-exposed stations there is a rapid increase in the vapour content soon of ter noon, especially in summer. The same is true of cloudiness, often greater on mountains than at lower levels, and usually greatest in summer when it is least in the lowlands. The higher Alpine valleys in winter have little cloud. This, combined with their low wind velocity and strong sunshine and the night temperature inver sions, makes them winter health resorts. Owing to forced ascent of air over rising ground, rainfall usually increases with height up to a certain point, beyond which, owing to loss of water vapour, this increase stops. The zone of maximum rainfall averages about 6,000f t. to 7,000ft. in altitude in intermediate latitudes, being lower in winter and higher in summer. When there is a prevailing wind from one direction, the lee side of the mountains, and the neighbouring lowlands, are relatively dry, forming a "rain shadow." Mountains resemble marine climates in having higher wind velocities than continental lowlands. Moun tain summits have a nocturnal maximum of wind velocity, while plateaus usually have a diurnal maximum.