Climatic History

CLIMATIC HISTORY. The geological history of the earth is divided into five main divisions, Archaean or Pre-Cambrian, Palaeozoic, Mesozoic, Tertiary and Quaternary periods (see GEOLOGY). These different periods contain evidence of many great changes of climate, but this article is limited to those which have occurred since the appearance of man. The earliest forms of man-like creatures probably appeared towards the close of the Tertiary period, and their development has been greatly influenced by a series of climatic changes which occurred during the Quater nary. The Tertiary is divided into Eocene, Oligocene, Miocene and Pliocene ; a fifth stage, the Pleistocene, is now generally included with the Quaternary. The Eocene began 6o million years ago, the Pliocene ended probably 600,000 to a million years ago. At the beginning of the Eocene the climate of middle latitudes was somewhat warmer than it is at present, and in the later Eocene and Oligocene it became very much warmer. Beds of fossil plants of warm temperate aspect dating from these periods have been found north of the Arctic Circle in many regions. In the Miocene the climate was somewhat cooler than in the Oligo cene, though probably warmer than the present. At the beginning of Pliocene times, ten to 15 million years ago, the climate of the north temperate regions again became warmer, but this was temporary, and towards the close of this period there was a rapid cooling. This change is well shown in East Anglia, where the earlier Pliocene beds contain mainly southern mollusca, while in the upper part of the Red Crag northern species become increasingly frequent. The later Pliocene beds of East Anglia, the Chillesf ord beds and Weybourne Crag, contain large num bers of arctic species, and are probably contemporaneous with the first glaciations of Scandinavia and the Alps. The latest bed in this country which was formerly attributed to the Pliocene, the Cromer Forest bed, indicates a return of somewhat warmer con ditions ; it is succeeded by boulder clays and other deposits of land ice, indicating the oncoming of glacial conditions in England itself. The discovery of Palaeolithic implements in this bed indi cates, however, that the forest bed and the underlying Wey bourne crag should be removed to the Pleistocene. The "Quater nary" Ice age began on the continent of Europe and in North America in the Pliocene, but it is convenient to ignore this some what arbitrary division and to consider the Ice Age as a whole.

The Quaternary Ice Age.—The Quaternary or Pleistocene Ice Age was characterized by the advance of great glaciers or ice sheets from a number of centres, of which the most important were Scandinavia and the Alps in Europe, the Cordilleras and various other centres in North America. Minor centres of glacia tion were located in Spitsbergen, Iceland, Ireland, Scotland and northern England, the Pyrenees, the Caucasus Range, the Hima layas, the mountain ranges of central Asia, Alaska and the whole chain of the Rockies and Andes, the highest mountains of equa torial Africa, south-eastern Australia and New Zealand. The ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica are remnants of the Quater nary glaciation, and illustrate the character of the great inland ice-sheets of northern Europe and North America.

Glaciation of the Alps.

The classical work of A. Penck and E. Bruckner in the Alpine region has shown that there were four main advances of the glaciers in Central Europe, which they designated Gunz, Mindel, Riss and Wurm. The intervening peri ods during which the ice retreated (interglacial periods) are termed Gunz-Mindel, Mindel-Riss and Riss-Wurm. In the Gunz glaciation the snow-line probably lay 3,900f t. lower than now, but the remains of this glaciation have been almost entirely oblit erated by the later advances. Of the Gunz-Mindel interglacial nothing is known with certainty, but from the amount of erosion performed by the rivers its duration is estimated as 6o,000 years. The Mindel glaciation was regarded by Penck and Bruckner as the greatest advance of the ice over the eastern half of the Alpine region. The snow-line lay about 4,25oft. below the present. The Mindel-Riss interglacial was very long (about 240,000 years), and for part of the time warmer than the present. The Riss was regarded as the greatest glaciation in the south-west and west, with a snow-line about 4,25oft. below the present. The Riss Wurm interglacial was relatively short (about 6o,000 years), but probably for a time warmer than the present. The Wurm glacia tion was considered by Penck and Bruckner to have been smaller in extent than the Riss (depression of snow-line 3,goof t. ), but the latest worker, W. Soergel, regards it as the greatest glaciation of the Alps. The Wurm was double, the two maxima being sep arated by a slight retreat. The final retreat of the ice was inter rupted by three re-advances, the Buhl, Gschnitz and Daun stages. The interval between the second maximum of the Wurm (Wurm II.) and the Buhl, which is important archaeologically, is termed the Achen oscillation. Penck and Bruckner estimated the length of the post-Wurm period as 20,000 years.Changes of Sea Level.—The changes of sea level during the Quaternary are best known from the work of E. Deperet in the Mediterranean. He recognizes f our shore-lines or raised beaches, representing periods when the sea was considerably above its present level. These were separated by periods of land elevation when the sea was below its present level and the Mediterranean was divided into two separate basins.

Glaciation in Northern Europe.

The history of the Scan dinavian ice-sheet is not known so fully as that of the Alps. The ice probably formed first on the Norwegian mountains, but the centre soon shifted to Sweden and the Gulf of Bothnia. The ice sheet extended into Russia, Germany, Denmark and Holland, and at its maximum filled the North Sea and encroached on the east coast of England, especially over East Anglia, where for a time it united with the ice from northern England. The edge of the ice-sheet over Europe underwent great fluctuations; it is not known with certainty whether it ever completely melted during the whole course of the Quaternary glaciation, but it is highly probable that this happened during at least the Mindel-Riss inter glacial. In East Anglia the Scandinavian ice was followed by English ice bearing great quantities of chalk, which formed the Great Chalky Boulder Clay, but the time relations of the various glacial deposits are not yet settled. Gerard de Geer's study of the deposits left by the retreating ice in Sweden has shown that the last ice-sheet began its final retreat about 20,000 years ago. As in the Alps, the retreat of the ice was interrupted by several re advances, indicated by great terminal moraines (see below).

North America.

In North America great ice-sheets reached lower latitudes than anywhere else on the earth. The ice spread out from three main centres, the Cordilleras in the west, the Keewatin west of Hudson's Bay, and Labrador in the east. The deposits of these various centres are complex, but a succession of five glacial and four interglacial stages has been made out in the Mississippi Valley. The latest glaciation, termed the Wisconsin, was double, like the Wurm, and de Geer has succeeded in cor relating the stages of its final retreat with those of the last Scan dinavian ice-sheet, but the relations of the earlier glacial stages with those in Europe are uncertain. Interglacial beds in Toronto indicate a long period of retreat and perhaps of complete disappearance of the ice, but their position in the Mississippi sequence is uncertain. In most other parts of the world the gla ciation has been shown to include three or four advances of the ice, indicating a general similarity with the sequence in the Alps, but direct correlation is not yet possible.

Stages of Human Culture.

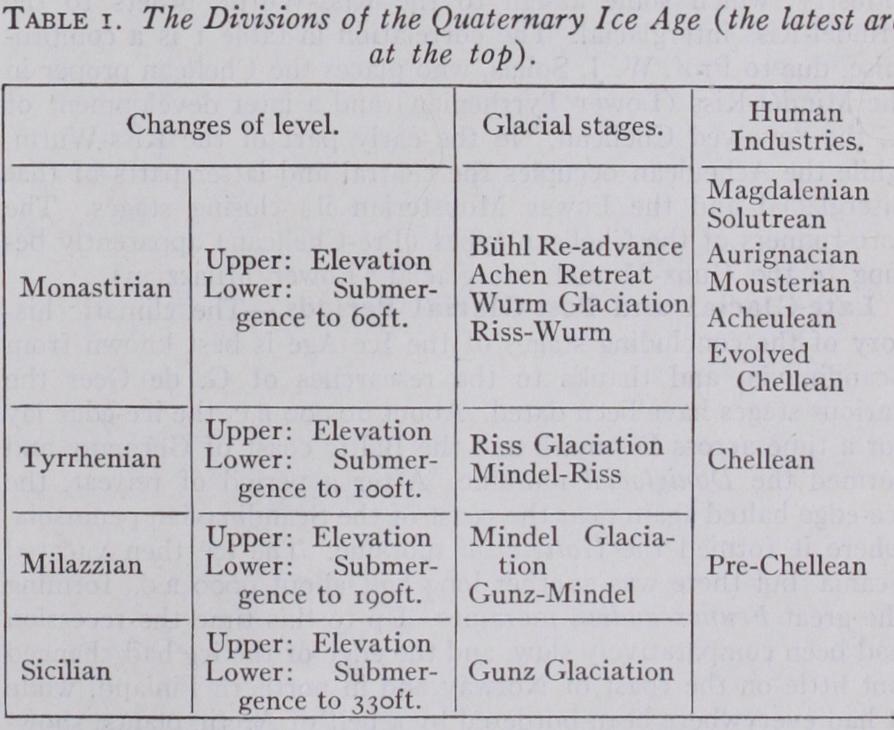

The Quaternary Ice Age roughly coincides with the Palaeolithic (q.v.) stage of human culture. The various industries into which the Palaeolithic of western Europe is divided are shown in table i with their probable positions in the glacial sequence, but there is still some doubt as to the early Palaeolithic. The Magdalenian falls in the period of arctic climate about the Buhl re-advance, while the Solutrean and Aurignacian occupy the Achen oscillation, a period of dry steppe-like climate which followed Wurm II. The whole of the Wurm glaciation (Upper Monastirian) is occupied by the Mousterian, which ex tends some way back into the Riss-Wurm interglacial (Lower Monastirian), but just how far is not quite settled. The contro versy has been concerned chiefly with the position of the Chellean industry, which some assign to the Riss-Wurm, others to the Mindel-Riss interglacial. The correlation in table i is a compro mise, due to Prof. W. J. Sollas, who places the Chellean proper in the Mindel-Riss (Lower Tyrrhenian) and a later development of it, the "evolved Chellean," in the early part of the Riss-Wurm, while the Acheulean occupies the central and latter parts of that interglacial and the Lower Mousterian its closing stages. The fore-runners of the Chellean types (Pre-Chellean) apparently be long to the Gunz-Mindel interglacial (Lower Milazzian).

Late-Glacial and Post-Glacial Periods.

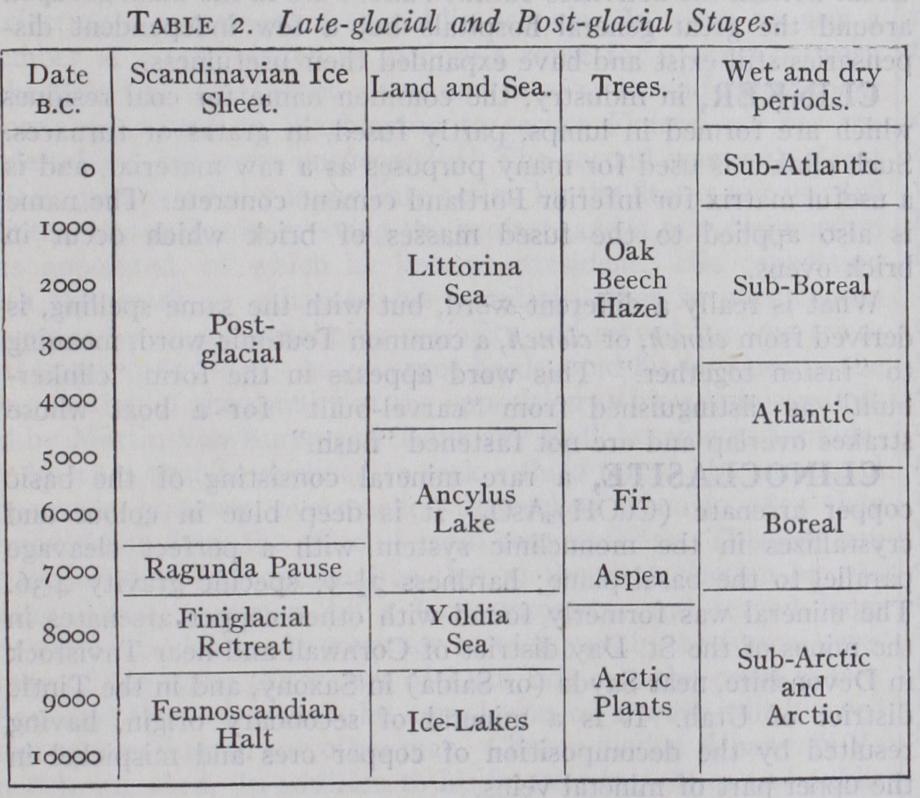

The climatic his tory of the concluding stages of the Ice Age is best known from Scandinavia, and thanks to the researches of G. de Geer the various stages have been dated. About 20,000 B.C. the ice-edge lay for a time across Denmark and the Baltic coast of Germany and formed the Daniglacial moraine. After a period of retreat, the ice-edge halted again near the coast of the Scandinavian peninsula, where it formed the Gotiglacial moraine. The ice then vacated Scania, but there was another long halt about goon B.c., forming the great Fennoscandian moraines. Up to this time the recession had been comparatively slow, and the edge of the ice had changed but little on the coast of Norway and in northern Finland, while it had everywhere been bordered by a belt of Arctic plants, show ing that the temperature was still very low. After the formation of the Fennoscandian moraines, however, there followed a period of very rapid retreat, termed Finigladial time, during which tem perate plants occupied almost immediately the ground vacated by the ice, indicating a comparatively high temperature. By about 700o B.c. the remnants of the ice-sheet had shrunk to a long narrow strip along the centre of Scandinavia. After a short halt termed the Ragunda Pause, the ice-sheet split into two sep arate portions about 650o B.c., and this date is regarded by Scan dinavian geologists as the "official" end of the Ice Age. The corre lation between the stages of retreat in Scandinavia and the Alps is not yet known, but it is not unlikely that the great Fennoscan dian moraines represent the Buhl stage.

In

Britain various Arctic plant beds are known which were presumably formed during the halts represented by the Gotiglacial and Fennoscandian moraines, and there were local re-advances of mountain glaciers in Scotland at the same times. The retreat stages of other centres of glaciation are not yet known in detail, but de Geer and Ernst Antevs have been able to date parts of the retreat stages of the ice-sheets in Canada and southern Argen tina by comparing the relative thicknesses of successive annual clay deposits with those in Sweden.

Changes in Land and Sea Distribution.

As the Scandina vian ice-sheet began to vacate the Baltic basin, the latter was occupied by a fresh-water lake, bounded on the north by the ice. After the formation of the Fennoscandian moraines a subsidence of the land allowed the ingress of the sea, both from the Atlantic across Scania and from the White sea across Finland. The site of the Baltic was now occupied by the Arctic sea, called the Yoldia sea from the presence of the high northern mollusc Yoldia arc tica. About the time of the Ragunda Pause the land rose again and both outlets to the ocean were closed. The Baltic now became a fresh-water lake, which from its characteristic mollusc is termed the Ancylus lake. The greater part of the Ancylus lake stage falls in post-glacial time, during which the last remnants of the ice sheet disappeared. About 400o B.C. a new period of submergence began in the south-west Baltic, again admitting the waters of the Atlantic and forming the Littorina sea. This sea was warmer and more saline than the present Baltic, because the inlet from the Atlantic was wider and deeper. The maximum subsidence prob ably occurred about 300o B.C., after which the land gradually rose again and conditions approached those of the present.A raised beach at a height of about ten ft. above the present beach is found almost all over the world, and in many parts is accompanied by a kind of fauna now known only from lower lati tudes. Such a widespread change of level indicates a rise of the sea, due to a greater volume of water in the oceans. The addi tional water can only have come from a melting back of the still existing ice-sheets, especially of Greenland and Antarctica, beyond their present limits; there is also independent evidence that this occurred. This general warm period is termed the Climatic Opti= mum; it falls somewhere within the time of the Littorina sea and probably between 2000 and moo B.C.

Vegetation.

Much information as to late-glacial and post glacial climates is provided by the vegetation, especially of peat bogs. In central Europe the Wurm glaciation was accompanied and followed by tundra, which gave place during the latter half of the Achen oscillation to dry cold steppe conditions during which Solutrean man, who hunted the horse, penetrated Europe from the east. In the Lower Magdalenian, the culture of which is based on the reindeer, conditions again became moister and colder, and the tundra returned for a short time, to be rapidly replaced by pine forest spreading up from the south-east. In the Upper Magdalenian the pine began to be replaced by dense forests of oak and the reindeer gave way to the red deer. Dense forests were almost impenetrable to primitive man, and in central Europe there is almost a gap—the "hiatus"—between Palaeolithic and neolithic industries.In Scandinavia the retreating ice-sheet was bordered by a broad zone of Arctic vegetation until the close of the Fenno scandian halt. The aspen appeared in the much warmer Finigla cial, the fir in the Ancylus period. The very favourable condi tions of Littorina time were marked by a wealth of new trees, including oak, hazel and beech; at one time the hazel greatly ex ceeded its present limits both of latitude and height.

Wet and Dry Periods.—The post-glacial period has had marked alternations of wet and dry climates, which were first set out by the Norwegian Axel Blytt. The time of the Ancylus lake was generally dry, with warm summers but cold winters; Blytt termed this the Boreal stage. The early part of Littorina time was moist, with very mild winters and summers probably as warm as at present, forming the Atlantic stage, which was marked by a great growth of peat in northern and western Europe. About 3000 B.C. the warm moist conditions gave way to a dry climate, with very warm summers and winters no colder than the present. The surfaces of the peat-bogs dried up, and in Scandinavia, Scotland and Ireland they were occupied by oak forests; in Germany there is instead a layer of dry heath peat. Blytt terms this the Sub Boreal period. About 85o B.C. there was a marked deterioration of climate, which became moist and cold, forming the Sub-Atlantic period, when the forests on the peat-bogs died and were replaced by a new and very rapid growth of peat. The change from the very favourable climate of the Sub-Boreal to the unfavourable climate of the Sub-Atlantic was very marked in the Alps; during the Bronze Age and the beginning of the Early Iron Age the cli mate was highly favourable and there was free communication across the passes; but early in the Iron Age the passes were closed and human occupation was banished to the lowest and warmest valleys, while at the same time many of the lake-dwellings were submerged. It seems probable that the Daun re-advance of the Alpine glaciers should be attributed to this stage; Penck and Bruckner dated the Daun re-advance as older than the Bronze Age, but on very scanty evidence.

The Boreal period is not well shown in the British Isles, but the succession of Atlantic peat, Sub-Boreal forest and Sub-Atlan tic peat is well seen in Ireland, most of Scotland and western England but not well developed in eastern England.

Summary.—The various late-glacial and post-glacial stages in Scandinavia may be summarized as follows: There is no clear boundary between the geological and historical periods, for in Egypt and south-west Asia the beginnings of his tory are almost contemporary with the end of the Ice Age in Scandinavia. In the arid regions of Arabia, Mesopotamia and central Asia variations of rainfall are of much greater importance than small variations of temperature, and this discussion is ac cordingly limited to the alternations of wet and dry periods.

Persia.

The semi-arid settlement of Anau on the northern margin of Persia is important. This site was occupied from time to time and abandoned during the intervening periods, and since there is no evidence of conquest, while the periods of abandon ment are represented by desert formations, it is highly probable that the interruptions were due to drought. These settlements were investigated by Mr. Raphael Pumpelly, who dated them by means of the relative thickness of deposits. According to Pumpel ly's estimates the first settlement began about 900o B.C., the sec ond, which immediately succeeded it, about 6000 B.c. The last part of the first settlement and the whole of the second show evidence of gradually increasing drought, and the site was abandoned soon after 6000 B.C. It was reoccupied, after an interval of desert con ditions, about 5200 B.C. The third settlement continued until about 2200 B.C., with a short interruption, probably due to drought, about 300o B.C. These estimates of the age of Anau appear to be far too great, and H. Peake and H. J. Fleure suggest that the first settlement did not begin till about 390o B.C., while the third settle ment lasted from about 2 50o to 1600 B.C. At the close of the third period there began a period of intense drought, and Anau was not reoccupied until the Iron Age, probably about 750 B.C.It is highly probable that in semi-arid regions the amount of unrest and migration increases during periods of drought, so that we can infer the variations of dryness from the frequencies of migrations. A period of extensive migration began about 265o B.C. and culminated between 2300 and 2050. Another maximum oc curred about 135o to 1300, after which the desert peoples began to settle down, and remained quiet until the Arabian dispersal of the seventh century A.D. (which began before the birth of Mo hammed) .

Caspian Sea.—During the Christian era our information is mainly derived from the variations of level of the Caspian Sea, amplified and supported by records of other lakes in Asia, and by Chinese archives. There is some doubtful evidence that the level of the Caspian was high about A.D. 0, but this is not confirmed by other sources. In the 5th century A.D. the Caspian was very low. Then follows a period of rapid fluctuations; high level about 920, low about 1125, very high from 1306 to 1325 and again early in the 15th century and about 156o to 164o.

Africa.—The evidence from northern Africa is mainly pro vided by the levels of the Nile floods, the history of Kharga Oasis, and the variations in the level of civilization in the Sahara. These point to a rainfall much higher than the present about 500 B.C., a minimum about A.D. 200, a slight improvement about 400, a very dry season from 700 to I 000, and a great improvement from about 1225 to 1300, followed by a decline to present conditions. It is interesting that E. J. Wayland has recently shown the existence of a marked dry period in central Africa in Neolithic times, prob ably representing the Sub-Boreal period.

America.

In North America the evidence is derived mainly from the width of the annual rings of growth of the "Big Trees" of California; the curve of tree growth can be checked and ad justed by the variations in the levels of the salt lakes of western America, and by archaeological evidence. The result shows that a long dry period ended about I000 to Boo B.C., followed by a period of high rainfall from 70o B.C. to A.D. 200, reaching a strongly marked maximum at 400 B.C. A long dry period began about A.D. 400 and continued until about I250, with one break at about moo, and there was a further dry spell in the 15th century.In Yucatan and central America the Mayan civilization reached its highest level apparently from 1 oo B.C. to A.D. 35o. After about 35o came the Mayan "Dark Ages," when southern Yucatan re lapsed into barbarism. A revival occurred about A.D. moo, but did not reach the level of the earlier period and probably lasted little more than two centuries. The ruins are now overgrown by dense forests, and Ellsworth Huntington makes the plausible assumption that the periods of high culture represent dry periods. If so, these are contemporaneous with the wet periods of Arizona, and represent a southward swing of all the climatic belts.

Recent excavations in southern Greenland have shown that its climate was far more favourable in the tenth century than it is to-day, and Baffin Bay seems to have been almost free of ice. There was a deterioration about A.D. I000, followed by a slight improvement during the Ilth and 12th centuries, after which the climate rapidly became very bad. The ground, which at first thawed to a considerable depth every summer, became perma nently frozen about A.D. 1400.