Climatic Subdivisions

CLIMATIC SUBDIVISIONS The Equatorial a few degrees of the Equator and when not interfered with by other controls, the annual curve of temperature has two maxima following the two zenithal posi tions of the sun, and two minima at about the time of the sol stices. This equatorial type of annual march of temperature is illustrated in the three curves for Brazzaville, Batavia and Ocean island (fig. 4) . The greatest range is shown in the curve for Brazzaville, inland in the Congo valley; the curve for Batavia il lustrates insular conditions with less range, and that for Ocean island oceanic conditions with a range of only 0.5° F.

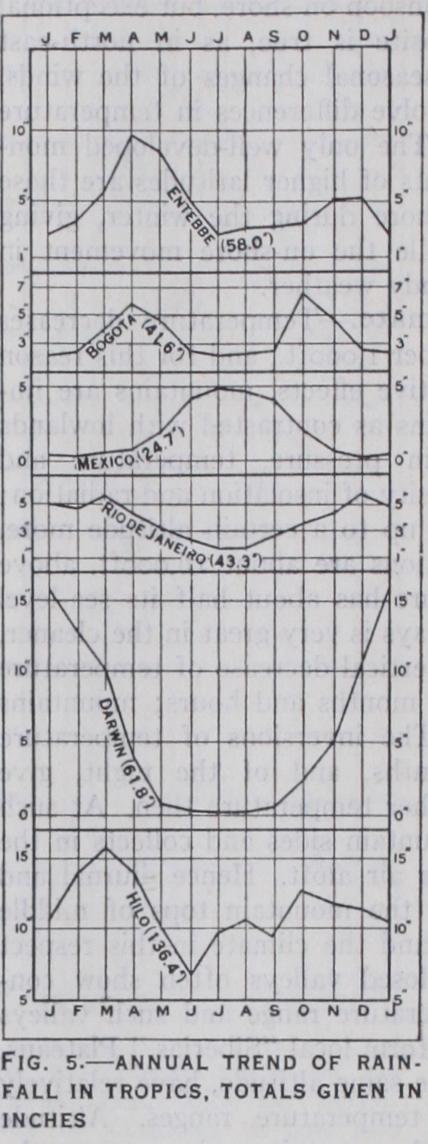

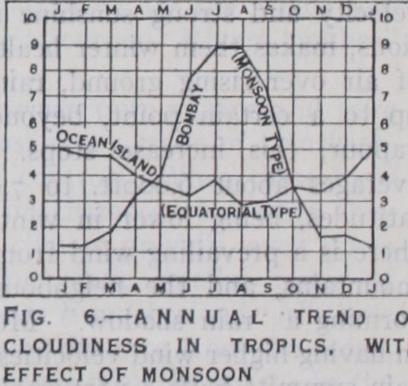

As the belt of rains swings back and forth across the Equator after the sun, there should be two rainy seasons with the sun ver tical, and two dry seasons when the sun is farthest from the zenith, and while the trades blow. These conditions prevail on the Equator, and as far north and south of the Equator (about io° I 2°) as sufficient time elapses be tween the two zenithal positions of the sun for the two rainy sea sons to be distinguished from one another. In this belt there is therefore normally no long dry season. The double rainy season is clearly seen in equatorial Africa and in parts of equatorial South America. The maxima lag somewhat behind the vertical sun, com ing in April and November, and the first is the greater one. The minima are also unsymmetrically developed, and the so-called "dry seasons" are seldom wholly rainless. This rainfall type with double maxima and minima has been called the equatorial type, and is il lustrated in the curves for Entebbe and Bogota (fig. 5). The an nual totals are given. These double rainy and dry seasons are easily modified by other conditions, as by the monsoons of the Indo Australian areas, so that there is no rigid belt of equatorial rains extending around the world. In South America, east of the Andes the distinction between rainy and dry seasons is often much con fused. The annual variation of cloudiness is illustrated by the curve for Ocean island (Oc) in fig. 6, but the annual period varies greatly under local controls.

At greater distances from the Equator than about z o° or 52° the sun is still vertical twice a year within the Tropics, but the interval between these two dates is so short that the two rainy seasons merge into one, in sum mer, and there is also but one dry season, in winter. This is the so called tropical type of rainfall, and is found where the trade belts are encroached upon by the equatorial rains during the mi gration of these rains into each hemisphere. It is illustrated in the curves for Sao Paulo, Brazil, and for the city of Mexico (fig. 5) . The tropical type of rainfall occurs beyond the margins of the region of equatorial rainfall and as we go farther towards the lines of the tropics the rainy season shortens to four months or less, lowlands often become parched during the long dry season (win ter), while life resumes activity when the rains return (summer). The Sudan receives rains, and its vegetation grows actively when the doldrum belt is north of the equator (May–August) . But when the trades blow (Decem ber–March) the ground is parched and dusty. The Venezuelan llanos have a dry season in the northern winter, when the trade blows. The rains come in May– October. The cameos of Brazil, south of the Equator, have their rains in October–April, and are dry the remainder of the year. The Nile overflow results from the rainfall on the mountains of Abyssinia during the northward migration of the belt of equatorial rains.

The so-called tropical type of temperature variation, with one maximum and one minimum, is illustrated in the accompanying curves for Wadi Halfa, in upper Egypt ; Alice Springs, Australia; Nagpur, India; and St. Helena (fig. 7). The effect of the rainy season is often shown in a displacement of the time of maximum temperature to an earlier month than the usual one as at Trade-Wind Belts.—The trade belts near sea-level have fair weather, steady winds, infrequent light rains or even an almost complete absence of rain, very regular, although slight, annual and diurnal ranges of tempera ture, and constancy and regular ity of weather. The climate of ocean areas in the trade-wind belts is indeed the simplest and most equable in the world, the greatest extremes over these oceans being found to leeward of the larger lands. On the lowlands swept over by the trades, beyond the polar limits of the equatorial rain belt (roughly between lats. 20° and 30°), are most of the great deserts of the world. These deserts extend directly to the water's edge on the leeward western coasts of Australia, Africa and America. Ranges and extremes of temperature are much greater over continental interiors than wer oceans in trade-wind belts. Minima of 32° or less occur luring clear, quiet nights, and daily ranges of over 5o° are :ommon. Midsummer mean temperature rises above 9o°, with loon maxima of 110° or more in the non-cloudy, dry air of a lesert day. The days, with high, dry winds, carrying dust and ;and, with extreme heat, accentuated by absence of vegetation, Ire disagreeable, but the calmer nights, with active radiation Hider clear skies, are much more comfortable. Nocturnal tem peratures are often low, and thin sheets of ice may form. While the trades are drying winds as long as they blow strongly wer the oceans, or over lowlands, they readily become rainy if cooled by ascent. Hence the windward eastern sides of moun tains or bold coasts in the trade-wind belts are well watered, while the leeward sides, or interiors, are dry. Mountainous islands in the trades, like the Hawaiian islands, many of the East and West Indies, the Philippines, Borneo, Ceylon, Madagascar, Tene riffe, etc., show marked differences of this sort. The eastern coasts of Guiana, Central America, south-east Brazil, south-east Africa and eastern Australia are well watered, while the interiors are dry. South America in the south-east trade belt is not well enclosed on the east and the most arid portion is an interior district close to the eastern base of the Andes where the land is low. Even far inland the Andes again provoke precipitation along their eastern slopes and the narrow Pacific coastal strip to leeward of the Andes is a very pronounced desert from near the equator to about lat. 3o° S. The cold ocean waters, with prevailing southerly (drying) winds alongshore, are additional factors caus ing this aridity. The rainfall associated with the conditions just described is known as the trade type, and has a maximum in winter when the trades are most active. In cases where the trade blows steadily throughout the year against mountains or bold coasts, as on the Atlantic coast of Central America, there is no real dry season. The curve for Hilo (mean annual rainfall in.) on the windward side of the Hawaiian islands, shows typical conditions (see fig. 5) .

Monsoon Belts.

In a typical monsoon region the rains follow the vertical sun, and therefore have a simple annual period much like that of the tropical type above described. This monsoon type of rainfall is well illustrated in the curve for Port Darwin in Australia (see fig. 5) . This sum mer monsoon rainfall results from the inflow of a body of warm, moist air from the sea upon a land area, the rainfall being par ticularly heavy where the winds have to climb over high lands. In India, the precipitation is heaviest in Assam (where Cher rapunji, at the height of 4,455ft. in the Khasi hills, has a mean an nual rainfall of between 400in. and sooin.), on the bold western coast of the peninsula (western Ghats) (12oin. and over), and on the mountains of Burma (up to 2 2 6in.) . In the rain-shadow of the western Ghats, the Deccan often suffers from drought and famine unless the monsoon rains are abundant and well distrib uted. The prevailing direction of the rainy monsoon wind in India is south-west ; on the Pacific coast of Asia, it is south-east. This monsoon district is very large, including the Indian ocean, Arabian sea, Bay of Bengal, and adjoining continental areas ; the Pacific coast of China, the Yellow and Japan seas and numerous islands from Borneo to Sakhalin on the north and to the Ladrone islands on the east. A typical temperature curve for a monsoon district is that for Nagpur, in the Deccan (fig. 7), and a typical monsoon cloudiness curve is given in fig. 6, the maximum coming near the time of the vertical sun, in the rainy season, and the minimum in the dry season.In the Australian monsoon region, which reaches across New Guinea and the Sunda islands, and west of Australia, in the Indian ocean, over latitudes o°-1o° S., the monsoon rains come with north-west winds between November and March or April. The general rule that eastern coasts between the Tropics are the rainiest finds exceptions in the case of the rainy western coasts in India and other districts with similar monsoon rains. On the coast of the Gulf of Guinea, for example, there is a small rainy monsoon area during the summer; heavy rains fall on the sea ward slopes of the Cameroon Mountains where Debundscha aver ages 369 inches. Goree, lat. 15° N., on the coast of Senegambia, gives a fine example of a rainy (summer) and a dry (winter) monsoon. In island groups such as the Malay Archipelago where trade winds alternate with monsoons the annual variation of rainfall becomes very complex.