Clock

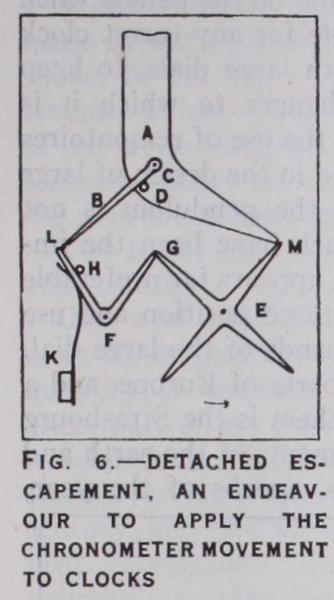

CLOCK MANUFACTURING—MASS PRODUCTION 1. Section of the power-press room in a clock factory 5. Final inspection and testing of alarm clocks in Brook 2. Automatic machines which turn out clock parts lyn, New York 3. Inspection of clock-movements in a large-scale prod uc- 6. Racks of kitchen clocks undergoing inspection after tion plant complete assembly 4. racks for electric switch clocks used in railway operation and urge it forward. As soon, however, as M has arrived at G the tooth M will slip off the block A and rest on the pall G, and the impulse will cease. The pendulum is now perfectly free or tached" and can swing unimpeded as far as it chooses. On its return from left to right, the pall B slips over pall L without turbing it, and the pendulum is still free to make an excursion towards the left. On its return journey the process is again repeated. Such an escapement operates once every two seconds, and consideration will show that it is only the application of the detached eter escapement to a clock. It will be found very easy to make by an amateur. The escapement has a large arc to act upon, being on the lower part of the pendulum.

A few attempts to combine the escape ment with the detached escapement have been made. One is shown in fig. 7. It is only a modification of the detached escape ment shown in fig. 6. It has worked very well for about 3o years, and seems to com bine efficiency with simplicity. The lower part of the pendulum A carries a flipper C which, as the pendulum passes from right to left, engages the end of the detent D, which, moving towards the left, releases E, a tooth attached to the gravity arm F, thus allow ing its end G to fall on the incline H, which is attached to the end of the pendulum. As soon as the pendulum has gone, F falls on an electric contact K, whereupon an electromagnet hoists it up again so that it falls on end E of the detent, and disjoins the elec tric contact at K, whereupon the electro-armature L resumes its position. On the return from left to right, the flipper C glides over the end of the detent D. The arrangement of the armature L is similar to one arranged by F. Hope Jones for electric clock winders. The object of making H double sided is that if the elec tricity ceases while the pendulum is swinging back from left to right, the part H shall not come into contact with G and be smashed, but simply slide over G. The escapement part of the clock is fixed on a frame attached to the suspension bracket of the pendulum by two steel rods of the same metal as the pendulum rod, so as to keep them in relative position in spite of temperature changes. The impulse given depends on the weight of the impulse arm. The work done in unlocking the detent is invariable, as it is independent of the electric drive.

The duration of the impulse is very short, only about one tenth of the arc of the swing. It is given exactly at the centre of the swing, and when not under im pulse the pendulum is detached.

Clock Wheels.—To keep the force which acts on the pendulum uniform is the object of the best escapement. Inasmuch as the impulse on the pendulum, derived from the work done by a falling weight or an unwinding spring, is transmitted through a train of wheels, it is desirable that trans mission should be as free from friction and as regular as possi ble. This involves care in the shaping of the teeth. The object to be aimed at is that as the wheel turns around, the ratio of the power of the driver to that of the driven wheel ("runner" or "follower") should never vary. The teeth of the wheels are given an epicycloidal form.

Going Barrels.—A clock must have some contrivance to keep it going while it is being wound up. In the old-fashioned house clocks this was done by what is called the endless chain of Huy gens. This kind of going barrel, however, is evidently not suited to an astronomical clock, and Harrison's going barrel is now universally adopted. Fig. 8 shows its construction. The click of the barrel-ratchet R is set upon another larger ratchet-wheel with its teeth pointing the opposite way, and its click rT is set in the clock frame. That ratchet is connected with the great wheel by a spring s's pressing against the two pins s in the ratchet and s in the wheel. When the weight is wound up (which is equivalent to taking it off), the click Tr prevents that ratchet from turning back or to the right ; and as the spring s's is kept by the weight in a state of tension equivalent to the weight itself, it will drive the wheel to the left for a short distance, when its end s is held fast, with the same force as if that end was pulled forward by the weight ; and as the great wheel has to move very little during the short time the clock is winding, the spring will keep the clock going long enough.

Remontoire.—To abolish er rors arising from the changes in the force driving the escapement, what is known as the "remon toire" system was adopted. It first came into use for watches.

The idea of remontoire is to dis connect the escapement from the clock-train, and to give the es capement a driving power of its own, acting as directly as possible on the pallets without the intervention of a clock-train. The escapement is thus made into a separate clock, which of course needs repeated winding, and this winding is effected by the clock-train. From this it results that variations in the force transmitted by the clock-train merely affect the speed at which the "rewinding" of the escapement is effected, but do not affect the force exerted by the driving power of the escapement.

There are several modes of carrying out this plan. The first of them is simply to provide the scape-wheel with a weight or spring of its own, which spring is wound up by the clock-train as often as it runs down. Contrivances of this kind are called train remon toires. In arranging such a remontoire it is obvious that the clock train must be provided with a stop to prevent it from overwinding the scape-wheel weight or spring, and further, that there must be on the scape-wheel a stud or other contrivance to release the clock-train as soon as the scape-wheel weight or spring has run down and needs rewinding. The first maker of a large clock with a train remontoire was probably Thomas Reid, of Edinburgh, who described his apparatus in his book on Horology (1819) . A clock at the Royal Exchange, London, was made in 1844 on this principle.

In these gravity remontoires, however, only the friction of the heavy parts of the train and the dial-work is got rid of, and the scape-wheel is still subject to the friction of the remontoire wheels, which though much less than the other, is still considerable. Ac cordingly, attempts have frequently been made to drive the scape wheel by a spiral spring, like the mainspring of a watch. Sir G. Airy invented one, of which one specimen is still going well.

General View of a Common Clock.

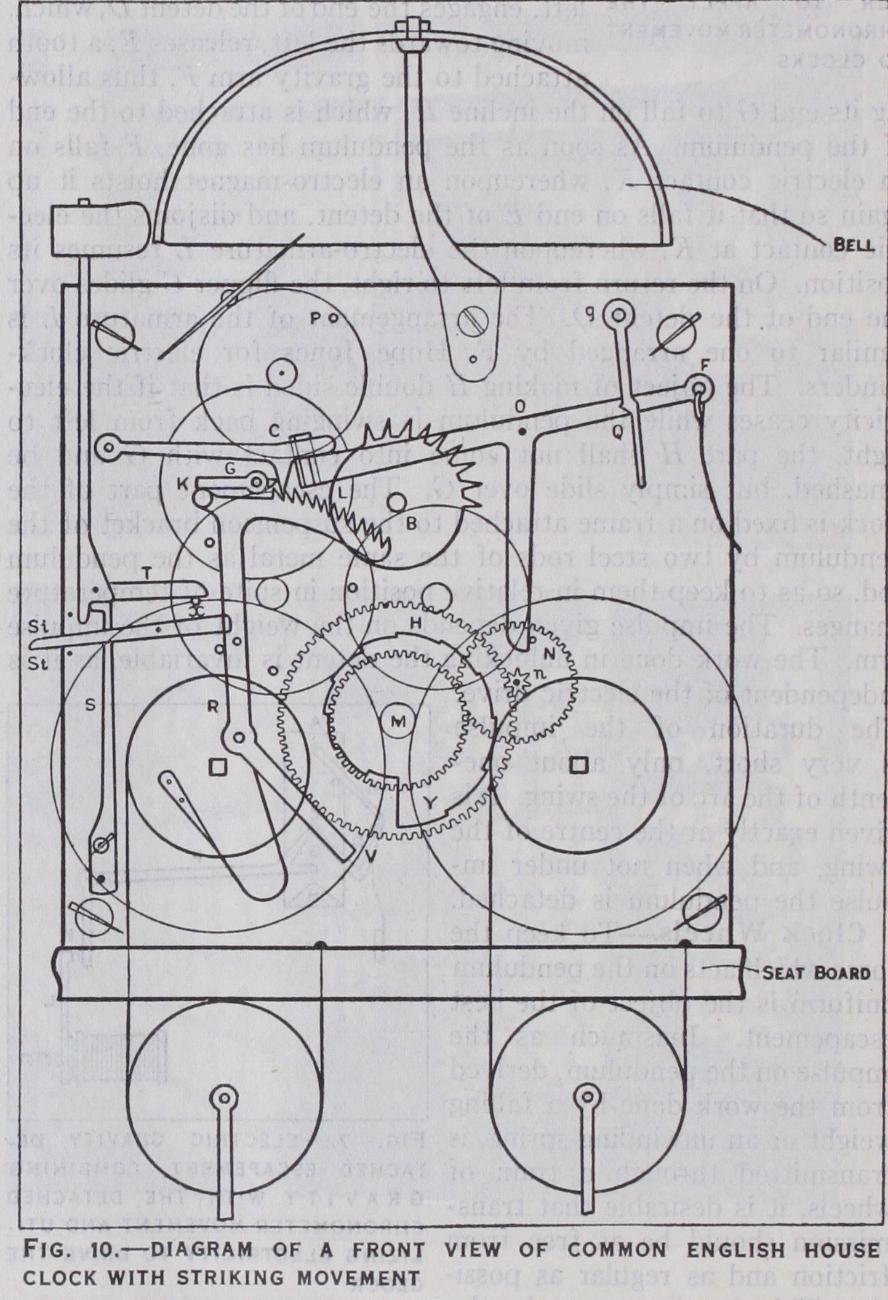

The general construc tion of the going part of all clocks, large or turret clocks, is sub stantially the same, and fig. 9 is a section of any ordinary house clock. B is the barrel with the cord coiled round it. The barrel is fixed to its arbor K, which is prolonged into the winding square coming up to the face or dial of the clock. The great wheel G rides on the arbor, and is connected with the barrel by the ratchet R, the action of which is shown more fully in fig. io. The great wheel drives the pinion c, which is called the centre pinion, on the arbor of the centre wheel C, which goes through to the dial, and carries the long, or minute hand. The centre wheel drives the second wheel D by its pinion d, and that again drives the scape wheel E by its pinion e. If the pinions d and e have each eight teeth or leaves, C will have 64 teeth and D 6o, in a clock of which the scape-wheel turns in a minute, so that the second hand may be set on its arbor prolonged to the dial. A represents the pallets of the escapements and their arbor a goes through a large hole in the back plate near F, and its back pivot turns in a cock OFQ screwed on to the back plate. From the pallet arbor at F descends the crutch Ff, ending in the fork f, which embraces the pendulum P, so that as the pendulum vibrates, the crutch and the pallets neces sarily vibrate with it. The pendu lum is hung by a thin spring S from the cock Q, so that the bending point of the spring may be just opposite the end of the pallet arbor, and the edge of the spring as close to the end of that arbor as possible.

The minute hand fits on to a squared end of a brass socket, which is fixed to the wheel M, and fits close, but not tight, on the prolonged arbor of the centre wheel. Behind this wheel is a bent spring which is set on the same arbor with a square hole in the middle, so that it must turn with the arbor ; the wheel is pressed up against this spring, and kept there by a cap and a small pin through the end of the arbor. The consequence is that there is friction enough between the spring and the wheel to carry the hand round, but not enough to resist a moderate push with the finger for the purpose of altering the time indicated. This wheel M drives another wheel N, of the same number of teeth, which has a pinion attached to it ; and that pinion drives the 12 hour wheel H, which is also attached to a large socket or pipe carrying the hour hand, and riding on the former socket. The weight W, which drives the train and gives the impulse to the pendulum through the escapement, is generally hung by a catgut line passing through a pulley attached to the weight, the other end of the cord being tied to some convenient place in the clock frame or seat-board, to which it is fixed by screws through the lower pillars.

Striking Mechanism.

Fig. i o is a front view with the face taken off, showing the repeating or rack-striking movement. M is the hour-wheel, on the pipe of which the minute-hand is set; N the reversed hour-wheel, and n its pinion, driving the i 2-hour wheel H, on whose socket is fixed what is called the snail Y, which belongs to the striking work exclusively. The hammer is raised by the eight pins in the rim of the second wheel in the striking train. The hammer does not quite touch the bell, as it would jar in striking and muffle the full sound. The form of the hammer-shank at the arbor where the spring S acts upon it is such that the spring both drives the hammer against the bell when the tail T is raised, and also checks it just before it reaches the bell, the blow on the bell thus being given by the bending of the hammer shank. Some times two springs are used, one for impelling the hammer and the other for checking it. But nothing will check the chattering of a heavy hammer, except making it lean forward so as to act, par tially at least, by its weight. The pinion of the striking-wheel generally has eight leaves, the same number as the pins ; and as a clock strikes 78 blows in i 2 hours, the great wheel will turn in that time if it has 78 teeth instead of 96, which the great wheel of the going part has for a centre pinion of eight. The striking-wheel drives the wheel above it once round for each blow; that wheel drives a fourth (in which there is pin P), six or any other integral number of turns for one turn of its own. A fan-fly moder ates the velocity of the train by the resistance offered by the air.

Church and Turret Clocks.

A clock is a machine in which the only work to be done is the overcoming of its own friction and the resistance of the air. It is evident that when the friction and resistance are much increased it may become necessary to neutral ize their effects. In a turret clock the friction is enormously increased by the great weight of all the parts and the resistance of the wind, and sometimes snow, to the motion of the hands. Besides that, there is the exposure of the clock to dirt and dust, and of the oil to a temperature which nearly or quite freezes it. This last circumstance alone will generally make the arc of the pendulum at least half a degree more in summer than in winter.Inasmuch as the time is materially affected by the force which arrives at the pendulum, as well as the friction on the pallets when it does arrive there, it is evidently impossible for any turret clock of the ordinary construction, especially with large dials, to keep any constant rate through the various changes to which it is exposed. Hence special precautions, such as the use of remontoires and gravity escapements, have to be observed in the design of large clocks in order to ensure that the arc of the pendulum is not affected by external circumstances. But such have been the im provements effected in electric clocks, that it appears far preferable to keep an accurate timepiece in some sheltered position and use it with a source of electricity to drive the hands of the large dial.

There are many turret clocks in various parts of Europe, and a limited number in England. The largest of them is the Strasbourg clock of 1547. It aims at showing the movements of the earth and stars as well as the time, also the seasons, epochs of the year, moral emblems and the life of man; it was restored in 1842. Some of these clocks contain large figures which strike the hours.

The Portable Clock.

Simultaneously with the development of the case clock, the watch was evolved. The need for it arose from the impossibility of moving the pendulum clock from place to place. The first use of a mainspring was probably in the 16th century. It was used for watches, then called Nuremberg eggs. The escapement was usually of the verge form with a crown wheel. A table clock, early i 7th century, is shown in the plate. The es capement is furnished with a balance wheel governed by a hair spring.The most usual pattern of portable clock in England (see Plate) has a pendulum of about io in. in length beating half seconds, a striking mechanism, shows the days of the month and dates from about the middle of the i8th century. After this period, the ten dency was for portable clocks to become smaller. In the Plate are shown two characteristic table clocks, one by the famous maker, Valliamy, and the other of a flat shape mounted in a gilt stand, suitable for travelling.

A great number of ornamental cases for portable clocks were made in the i8th and i 9th centuries. A rather handsome one is shown in the Plate. It is of enamelled copper, mounted in gilt frames. It has on the reverse side five dials showing the positions of the moon and planets. It has also a repeater, which, by pulling a string, causes the hour to sound whenever wanted. This is an old plan much used before the invention of lucifer matches.

Two hands for clocks came in about the commencement of the i8th century.

Old and Modern Clocks Compared.—Of old makers the most distinguished was Thomas Tompion, at whose works a vast quantity of beautiful clocks and watches were made during the latter part of the i 7 th century. He is called the father of English watchmaking. The name next to Tompion is that of his pupil, George Graham, who flourished during the early part of the i 7th century, and who invented the mercurial pendulum and the dead beat escapement. Quare is another maker whose clocks are valuable. A collection of stand clocks is to be seen at the South Kensington museum.

Robert Hooke (q.v.) was the first who drew attention to the fact that springs when stretched resist with a force proportional to their extension, and thus helped to lay the foundation of the laws of harmonic motion as applied to clockwork. He also invented a wheel-cutting device and the anchor escapement.

Huygens was one of the originators of the application of the pendulum to the clock and the inventor of the going barrel. Har rison invented the "grid-iron" pendulum, and also enormously improved the chronometer, by means of which he proved that the Board of Admiralty was a whole day's sail out of the proper reckoning of the island of Madeira. This chronometer in one experiment kept time to within 65 minutes in about five months, which was a wonderful performance in those days, for it was then thought quite a feat to determine the position of a ship at sea by means of a chronometer to 4o miles.

Modern household clocks are now made with short i o in. pendulums, and frequently are wound up by electricity at short intervals. Companies provide master-clock control for hotels and public buildings. These clocks do not aim at the accuracy of astronomical clocks, but they are admirably adapted for the uses of ordinary life.

Electrical Clocks.—Electrical timepieces only differ from timepieces driven by weights or springs in that some arrangement is made to use electricity to wind up those weights or springs mechanically, either at every beat of the pendulum or at intervals. With dry batteries small clocks can be made to run for a long time without attention. For bigger clocks it is possible to use the electric lighting supply. This is not difficult where the current is continuous, but where it is alternating, a transformer or a special synchronous design known as the telechron (q.v.) is used. An ingenious form is the well-known Hipp's clock at the observatory of Neuchatel in which, as the pendulum passes its lowest point, a vertical flipper is made to close an electrical circuit. Its average variation from its daily rate is about one-thirtieth of a second.

The bibliography of horology is very extensive. Among modern works Lord Grimthorpe's Rudimentary Treatise on Clocks, Watches and Bells (8th ed., 1903; is perhaps the most convenient. Many references to older literature will be found in Thomas Reid's Treatise on Clocks and Watchmaking (1849). (H. H. C.)