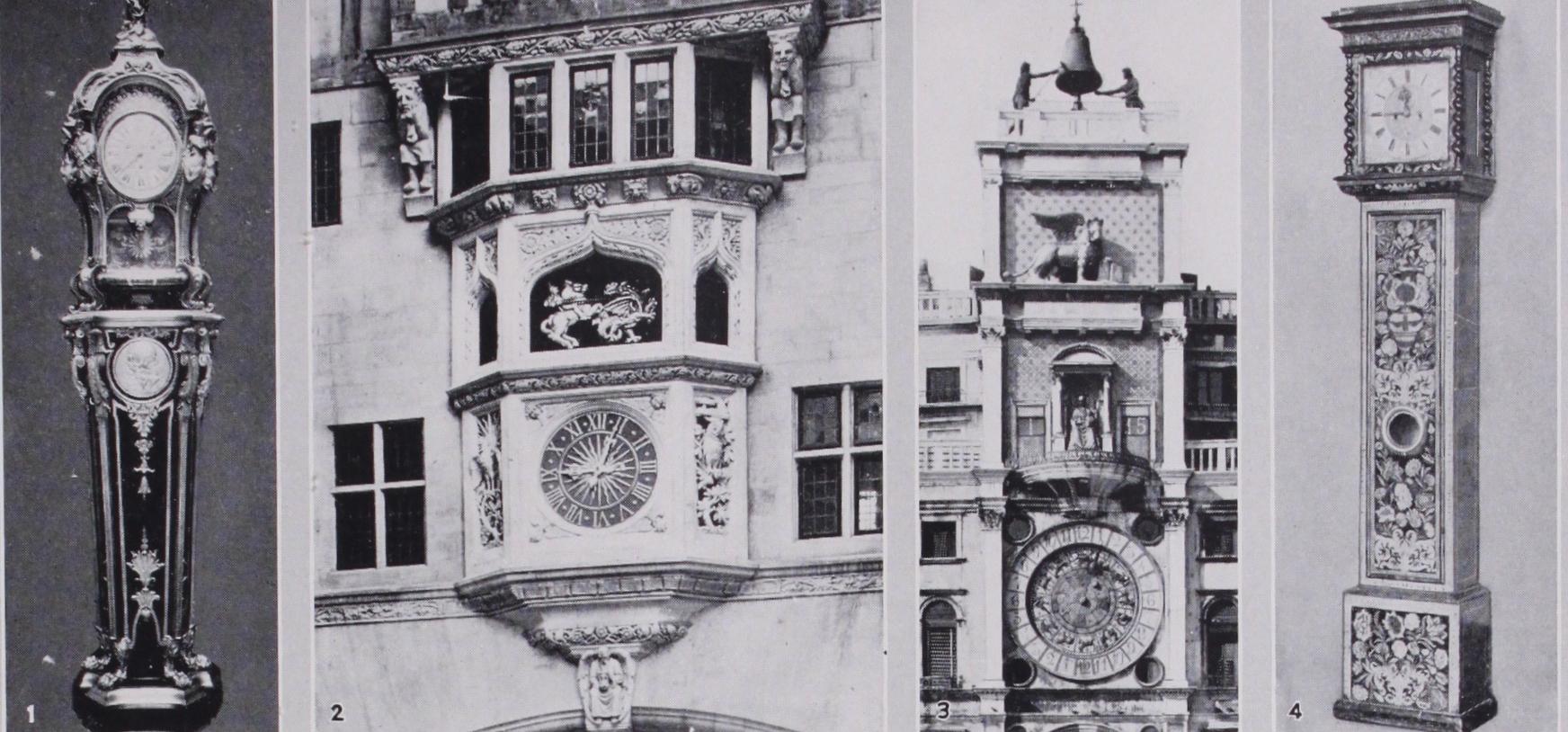

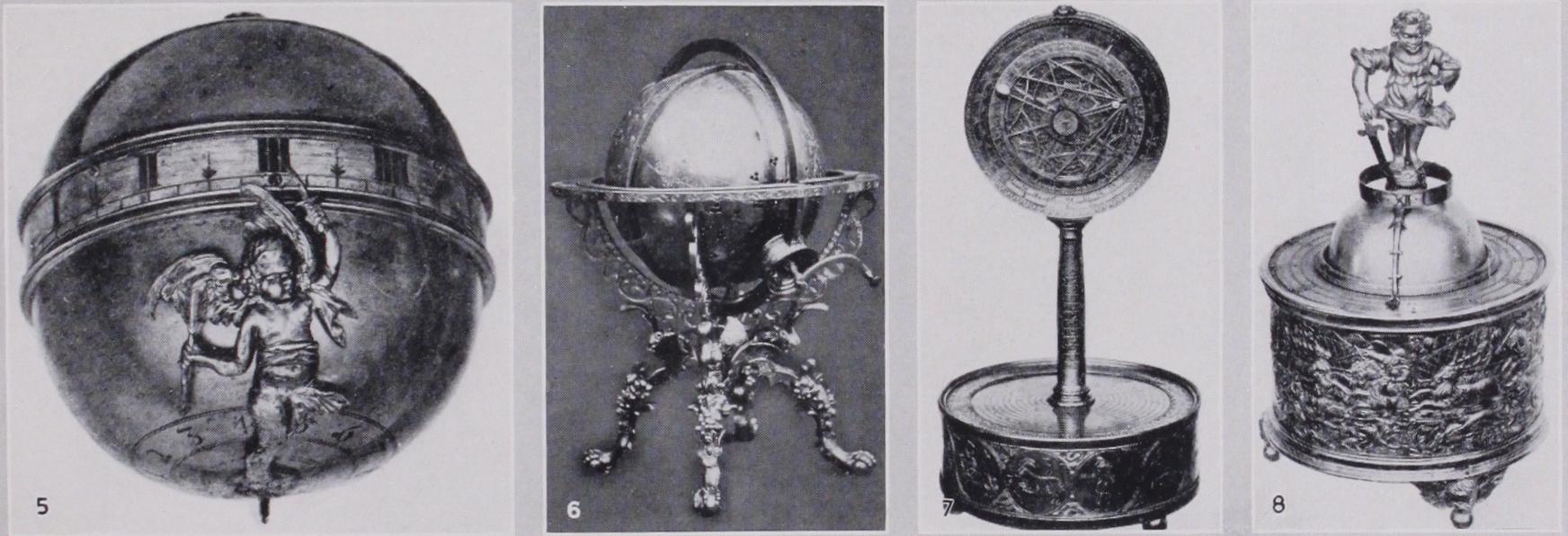

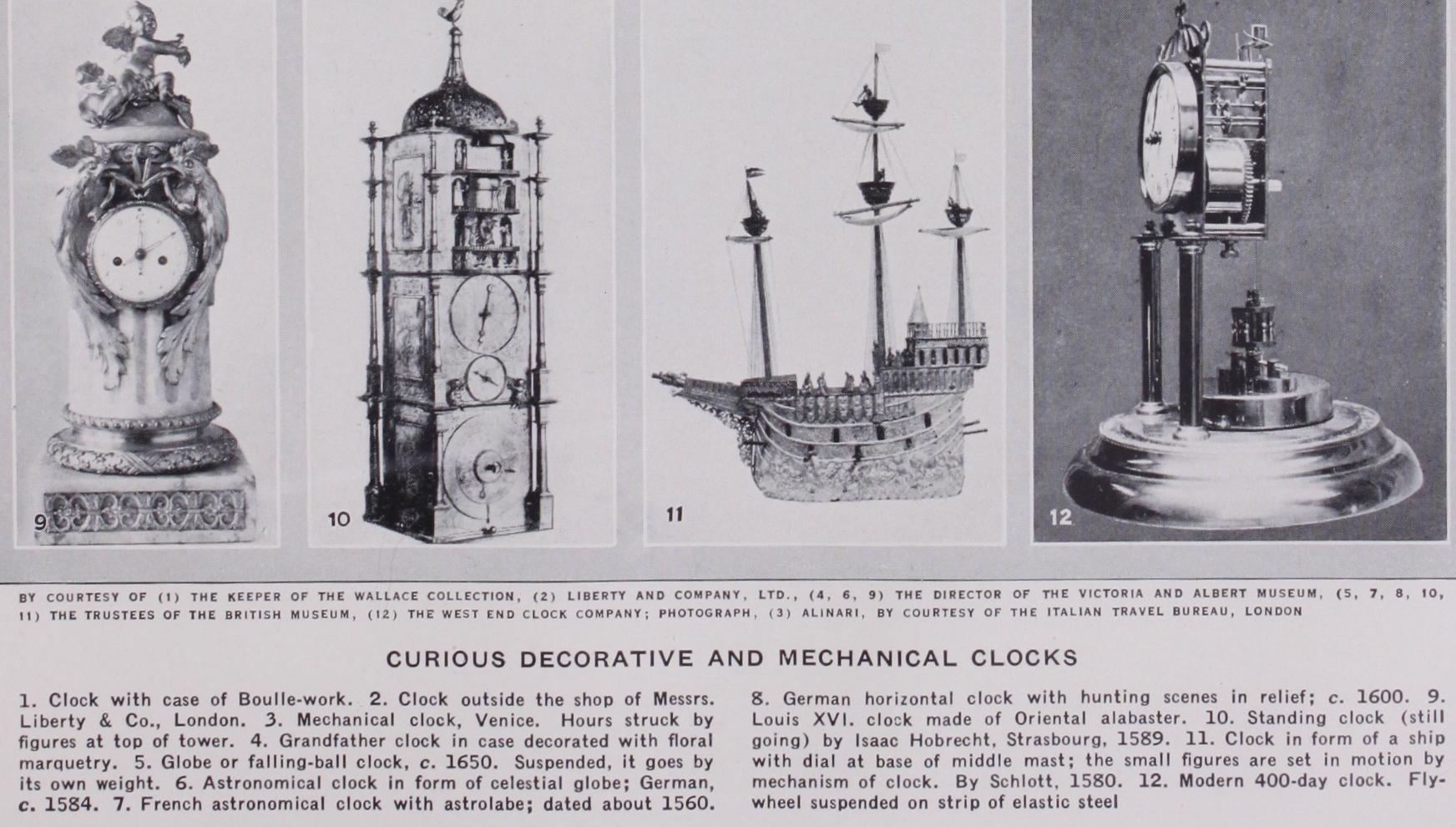

Clocks

CLOCKS. A clock consists of a train of wheels, actuated by a spring or weight or other means, and provided with an oscillating governing device which so regulates the speed as to render it uniform. Generally it has a mechanism by which it strikes the hours on a bell or gong (Fr. cloche; Ger. Glocke, a bell) whereas a timepiece simply shows the time.

History of Clocks.

The earliest clocks seem to have come into use in Europe during the 13th century, although there is evidence that they may have been invented some centuries sooner. The invention of the first clock is ascribed to Pope Silvester II. in A.D. 996. A clock was put up in a former clock-tower at West minster in 1288, one in Canterbury cathedral in 1292, and another at St. Albans in 1326 which showed various astronomical phenom ena. One placed in Dover Castle in 1348 was exhibited, going, in the Scientific Exhibition of 1876.All these old clocks had the duty of keeping time. They were corrected occasionally by sundials or by crude astronomical obser vations. But sundials were of little use on dull days, and observa tories were very few and maintained mainly for astrology. But now the world is well supplied with observatories at which the correct time can be most accurately determined and communicated electrically to any point. The problem thus is to devise some simple mechanism that will have a steady rate for short intervals that can be accurately observed. It is the rate of going that is important. If we know the rate of error of a clock we can allow for it in an observatory or neglect it in common life. Our real timekeeper is the stars. The time is set all over the world by the consensus of a host of observatories.

Clock Motion.

The oscillating body, which regulates the rate of going, must have mass and movement, and must be kept going by the expenditure of force.Two weights of equal mass, one at each end of a rod, might be swung in a circular path, and a spring of some sort might be fixed to them so as to gradually retard their motion. This was the first idea of the 14th century clock-makers, and on it the Glas tonbury clock was designed. The method of attaching the spring was very clumsy, and quite destructive of accuracy. It is shown in fig. I and is called the verge es capement. A rod or verge has weights at tached to each end AB; it is then fixed at right angles to a horizontal axis C which is mounted on pivots in proximity to a horizontal crown wheel E. The "pallets" FG are mounted on the horizontal axis so as alter nately to engage the opposite teeth of the crown wheel. The crown wheel is caused to rotate by a cord and weight H. As it goes round, one of the pallets engages with a tooth, the swing of the verge is stopped, and the verge is given a swing in the opposite direction. The process is then repeated—the other pallet engaging a tooth on the other side of the crown wheel. Very heavy balls are needed to keep the period of oscillation approximately uniform. The friction on the axis, caused by the weight of the balls, is largely destructive of accuracy.

The Pendulum.

The verge escapement led to the idea of one ball at the lower end of a rod suspended by a flexible metal band. Such a ball was found to swing in periods which were very nearly uniform when the swings were not very unequal in amplitude. The time of swing varies with the square root of the length of the pendulum, and changes very little when the arc is slightly changed. When the length of the pendulum rod was 39-14 in., a difference of in. of length was found to make the clock go slower by about a second a day; and when the arc of vibration of 3 in. was increased by in., the clock was again found to go slower by about a second a day. It is possible to express the time of going of a clock by a formula. Thus, let L be the length of the pendulum in.), G twice the distance that a weight will fall to the earth in one second (32 ft.), r the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter (3.1415), and M the arc of swing in inches.Then the time of a single swing in seconds very nearly.

Compensation of Pendulums.—The equation given above, as well as practice, indicates that the time of swing of a pendulum is altered by temperature. The expansion of steel is about •000 in. for each increase of 4° of temperature. The effect of tempera ture on the length and time of a particular pendulum can be com puted. If a vessel of mercury about 7 in. in height is placed so as to rest on the bottom of an iron pendulum rod, it will expand so that the distance of its centre from the point of suspension is practically constant with varying temperatures. The use of the steel alloy (invar), which expands by heat only about one-tenth of the amount of ordinary steel, has greatly simplified the con struction of accurate pendulums. There are several other factors which affect the real length of the pendulum, but, for reasons that have been explained, it is daily becoming less important to have extraordinary means of effecting compensation even in astronomical clocks. The true method of correction is by means of stellar observation. The heat compensator is a needful adjunct to every clock that aspires to be more than a mere old "grand father," but fine mechanical regulation is less necessary than in former years.

Escapements.—The term escapement is applied to any arrange ment by which, as the wheels rotate, periodic impulses are given to the pendulum, while at the same time the motion of the wheels is arrested until the vibration of the pendu lum has been completed. The escapement thus serves as a mechanism for both counting and impelling the pendulum and adapting the length of its swing to the im pulse it has received. The best escapement is one which gives an impulse to the pendu lum for a short period at the lowest point of its path, and then leaves it free until the time comes for the next impulse. It is also desirable that the impulses given to it shall be equal. The driving force of the escape ment varies with the amount of energy ab sorbed by friction and with the thickness of the oil. It is therefore desirable to secure uniformity of impulse; e.g., by causing the train of wheels to lift a weight and let its drop act on the pendulum at regular intervals.

The two requirements above stated have given rise respectively to what are known as detached escapements and remontoires, which will be described presently. In the first place, however, it is desirable to describe the principal forms of escapement in ordinary use. The balance escapement was in use before the days of pendulums. It was to a balance escapement that Huygens applied the pendulum, by removing the weight from one arm and increasing the length of the other arm. Very shortly afterwards R. Hooke invented the anchor or recoil escapement. This is repre sented in fig. a, where a tooth of the escape-wheel is just escaping from the right pallet, and another tooth at the same time falls upon the left-hand pallet at some distance from its point. As the pendulum moves on in the same direction, the tooth slides farther up the pallet thus producing a recoil, as in the crown-wheel or verge escapement. To get rid of this defect the dead escapement, or, as the French call it, l'echappement a repos, was invented by G. Graham. It is represented in fig. 3. The teeth of the scape wheel have their points set the opposite way to those of the recoil escapement. The tooth B is here represented in the act of drop ping on to the right-hand pallet as the tooth A escapes from the left pallet. But instead of the pallet having a continuous face as in the recoil escape ment, it is divided into two, of which BE on the right pallet, and FA on the left, are called the impulse faces, and BD, FG the dead faces. The dead faces are portions of circles (not necessarily of the same circle), having the axis of the pallets C for their centre ; and the consequence evidently is that, as the pendulum goes on, carrying the pallet still nearer to the wheel than the position in which a tooth falls on to the corner A or B of the impulse and the dead faces, the tooth still rests on the dead faces without any recoil, until the pendulum re turns and lets the tooth slide down the im pulse face, giving the impulse to the pendu lum as it goes. In order to diminish the friction and the necessity for using oil as far as possible, the best clocks are made with jewels (sapphires are the best) let into the pallets.

The pallets are generally made to embrace about of the cir cumference of the wheel, and it is at all desirable that they should embrace more ; for the longer they are, the longer is the run of the teeth upon them, and the greater the friction. A not uncommon proportion is that out of a total arc of swing of 3°, or about i ° on each side of the vertical, are occupied in receiv ing the impulse. In other words, the points F and A should sub tend an angle of a ° at the centre C. It is not to be forgotten that the scape-wheel tooth does not overtake the face of the pallet immediately, on account of the moment of inertia of the wheel.

One of the great obstacles to accurate timekeeping was that the train of wheels which drives the escapement is liable to varia tion of force. This is chiefly caused by cold, which thickens the oil, by wear of the parts, and by grit which gets into them. To obviate this an old suggestion was that the scape-wheel teeth should not be made to act directly on the pallets, but that each of them as it revolved should lift a weight which then fell on the pallets with a force which was nearly in variable. The scheme, however, was diffi cult to work out practically until Bloxam, a barrister, invented what is called the three legged gravity escapement (fig. 4). As the pendulum swings out it lifts alternately the arms pivoted round centres C. This draws away the detents E and F, and allows the escape-wheel to rotate. But instead of the pendulum receiving its impulses from the pins on the escape-wheel, it receives them from the arms which are actuated by grav ity, and all the escape-wheel does is to lift those arms and then release them. Lord Grimthorpe unproved this escapement by adding a fly-vane to give a gentle move ment to the escape-wheel and prevent bang ing. Big Ben at Westminster, London, was made with this gravity escapement and has gone excellently for over half a century.

One of the great difficulties in all these old escapements was that the driving force which impelled the pendulum on the one side and received its return impulses on the other was connected through all its motion with the pendulum rod. Now one of the necessities for true harmonic motion is to kick a mass into space, and let it swing freely till it came to rest and then swing back freely. Hence it was desirable as soon as the scape-wheel had delivered its impulse, to detach it from the pendulum, and then only let the pendulum come in contact with it again on its jour ney—in other words, to cause the action between the scape-wheel and pendulum to take place only at the centre of the swing. This gave rise to the chronometer spring escapement. All that need be done is to fix on to the pendulum a small ratchet or flipper ar ranged so as to push as it goes one way and miss as it returns (fig. 5). This flipper acts on a detent. When it pushes the detent one way, the detent releases an arm which gives the flying pendulum a push. But as the pendulum returns, the flipper passes the detent and allows the pendulum to swing free. Thus the pendulum receives an impulse on every alternate swing. A great many escapements have been designed on this plan for chronometers. One was in vented by Robert Houdin, the conjurer, about 183o, and another by that great gen ius Sir George Airy (q.v.). A simple form (fig. 6) was designed by Sir Henry Cunyng 'hame and has been keeping good time for the last 3o years. Its chief merit is that it does not depend for accuracy on expensive making. Let A be a block of metal fixed to the lower end of the pendulum rod ; on this block let a small pall be fastened free to move round a centre C and resting against a stop D. Let E be a four-leaved scape-wheel, the teeth of which as they come round rest against the bent pall GFL at G. The pall is prevented from flying too far back by a pin H, and kept up to position by a very delicate spring K. As soon as the pendulum rod, moving from right to left, has arrived at the position shown in the figure, the pall B will engage the arm FL, force it forwards, and liberate the scape-wheel, a tooth of which, M, will thus close upon the heel of the block A, <;,,,..;;;;;;,77'. r 1 " r P rpm ,/% pill, ,,,:, . ,- ' '''.' , , . 1, ‘Nt - , ' i i ' ' . . - - , . -,--- -' - :,' - ,,,,,, -„, - 0* , , ,,, / '-_, / -- ‘...,..,„,;" , V- . 1 0 . ,' '''''''' s ' ' -..' — ' ', _ .-„..;,,,,., , , , , Vit, ' ' ,,. 1. ', i v , i ',.,:44., , ' ' . ,.. 'I. * 1 . '''-' j ogail** ' '''' ' ' 'St ‘ i --- '' ' ' ' \ ' i' ‘ . itumi:s1 ..-,';',-- , ' / 11111- ' , - 4 I • ' ', , , , , 4 ..,... r r '.. ' -,,....... ,., ili II ,,,, '', : I t'` -„ ' s ,, £ 1 i f`- Ir , , JH \ - w y$g w , .,.;',,,,,,,,,, .,,,,..,, , : ' , , ' .

SI^ ..

_ - f .., /•, ..ter •/ `:i' . \ fi J 'web y ".-" r '.. ''.., ,.**'''''''':.„ ' '' /1- \-' F °Nr.

pil,,,, ,-. i • ..rrF„ ', y J Y / !r/ e.-yH,/i` v _,----, ' ii f - :''• i' 0 't l'It-'.': '-mil M p,urtl ''''' .,..... .• . z ram 1 ' 3 ' ;' ems. - P) , '''''','''''''''''' 47"'-'!'...„,,,, * '!4t...' ' ' ' ', ".-- ':' . ' f '1:: i'''''' -",'0,..'..'i.4.? - .';',.,S,t,'‘ Iti 4 , /£ / yi / / ' 09,,II, i Rf a j " I 1414,* krn.- ,Inal; m ,,- ,,,_ .,„„ A ,,, __. , _:-- . - ,, 1., - t tt ass ' , ° , / I t ' , , . . ,,,- ,,,,„ , A i ' ' i i„ t r € s 6