Cloister

CLOISTER originally signified an entire monastery, but is now restricted to mean the four-sided enclosure, surrounded with covered ambulatories, usually attached to conventual and cathe dral churches, and sometimes to colleges, or, by a still further limi tation, to the ambulatories themselves. In its older sense it is fre quently used in earlier English literature and is still so employed in poetry. The Latin claustrum, as its derivation implies, pri marily denoted the enclosing wall of a religious house, and then came to be used for the whole enclosed building. To this sense the German Kloster is still limited, the covered walks, or cloister in the modern sense, being called Klostergang, or Kreuzgang. In French the word cloitre retains the double sense. In the special sense now most common, the word "cloister" denotes the quadri lateral area in a monastery or college, round which the principal buildings are ranged, and which is usually provided with a covered way or ambulatory running all round, and affording a means of communication between the various centres of the ecclesiastical life. According to the Benedictine arrangement, which from its suitability to the requirements of monastic life was generally adopted in the West, one side of the cloister was formed by the church, the refectory occupying the side opposite to it, so that the worshippers might have the least annoyance from the noise or smell of the repasts. On the eastern side the chapter-house was placed, with other apartments adjacent to it, belonging to the common life of the brethren, and, as a rule, the dormitory occu pied the whole upper story. On the opposite or western side were generally the cellarer's lodgings, with the cellars and store-houses, in which the necessary provisions were housed. In Cistercian monasteries the western side was usually occupied by the domus conversorum, or lodgings of the lay-brethren, with their day rooms and workshops below, and dormitory above. The cloister, with its surrounding buildings, generally stood on the south side of the church, to secure as much sunshine as possible. A very early example of this disposition is seen in the plan of the mon astery of St. Gall. Local requirements caused the cloister, in some instances, to be placed to the north of the church. This is the case at Canterbury, Gloucester, Chester and Lincoln cathedrals.

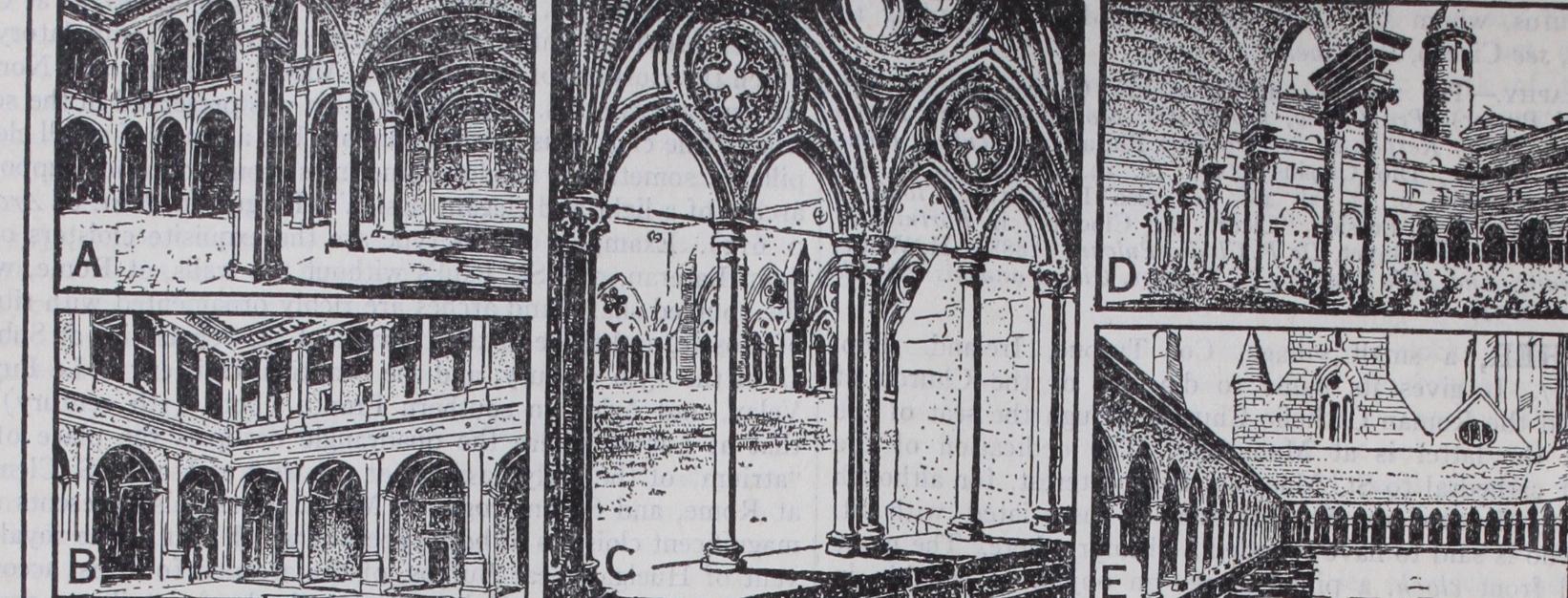

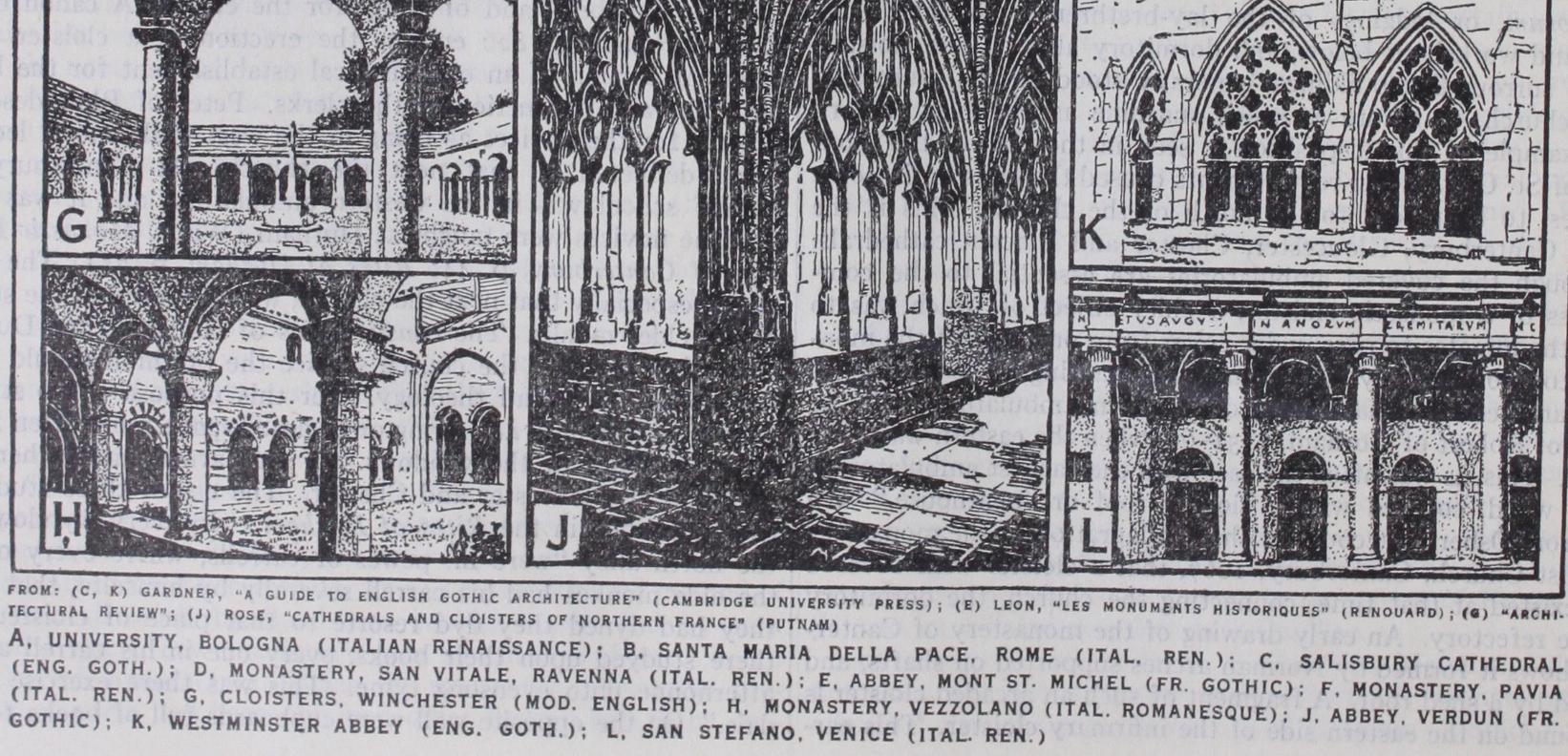

Although the covered ambulatories are essential to the com pleteness of a monastic cloister, a chief object of which was to enable the inmates to pass under cover from one part of the mon astery to another, they were sometimes wanting. The cloister at St. Albans seems to have been deficient in ambulatories till the abbacy of Robert of Gorham, 1151-66, when the eastern walk was erected. This, as was often the case with the earliest ambulatories, was of wood, covered with a sloping roof or "penthouse." We learn from Osbern's account of the conflagration of the monastery of Christ Church, Canterbury, 1067, that a cloister with covered ways existed at that time, connecting the church, the dormitory and the refectory. An early drawing of the monastery of Canter bury shows it formed by Norman arches supported on shafts, and covered by a shed roof. A fragment of such an arcaded cloister is still found on the eastern side of the infirmary cloister. This ear Tier form of cloister has been generally superseded in England by a range of windows, usually unglazed, but sometimes, as at Glou cester, provided with glass, lighting a vaulted ambulatory, of which the cloisters of Westminster Abbey, Salisbury and Norwich are typical examples. The older design was preserved in the south, where "the cloister is never a window, but a range of small elegant pillars, sometimes single, sometimes coupled, and supporting arches of a light and elegant design" (Fergusson, Hist. of Arch, i., p. 610). Examples of this type are the exquisite cloisters of St. John Lateran, and St. Paul's without the walls, at Rome, where the coupled shafts and arches are richly ornamented with ribbons of mosaic, and those of the convent of St. Scholastica at Subiaco, all of the 13th century, and the beautiful cloisters of Le Puy-en and Arles, in southern France (both nth century) and that at Laach, where the quadrangle occupies the place of the "atrium" of the early basilicas at the west end, as at S. Clemente at Rome, and S. Ambrogio at Milan. Spain also presents some magnificent cloisters of both types, of which that of the royal con vent of Huelgas, near Burgos, of the arcaded form, is, according to Fergusson, "unrivalled for beauty both of detail and design." Also notable are those of Monreale and Cefalu in Sicily (12th century), where the arrangement is the same, of slender columns in pairs with capitals of elaborate foliage supporting pointed arches of great elegance of form.

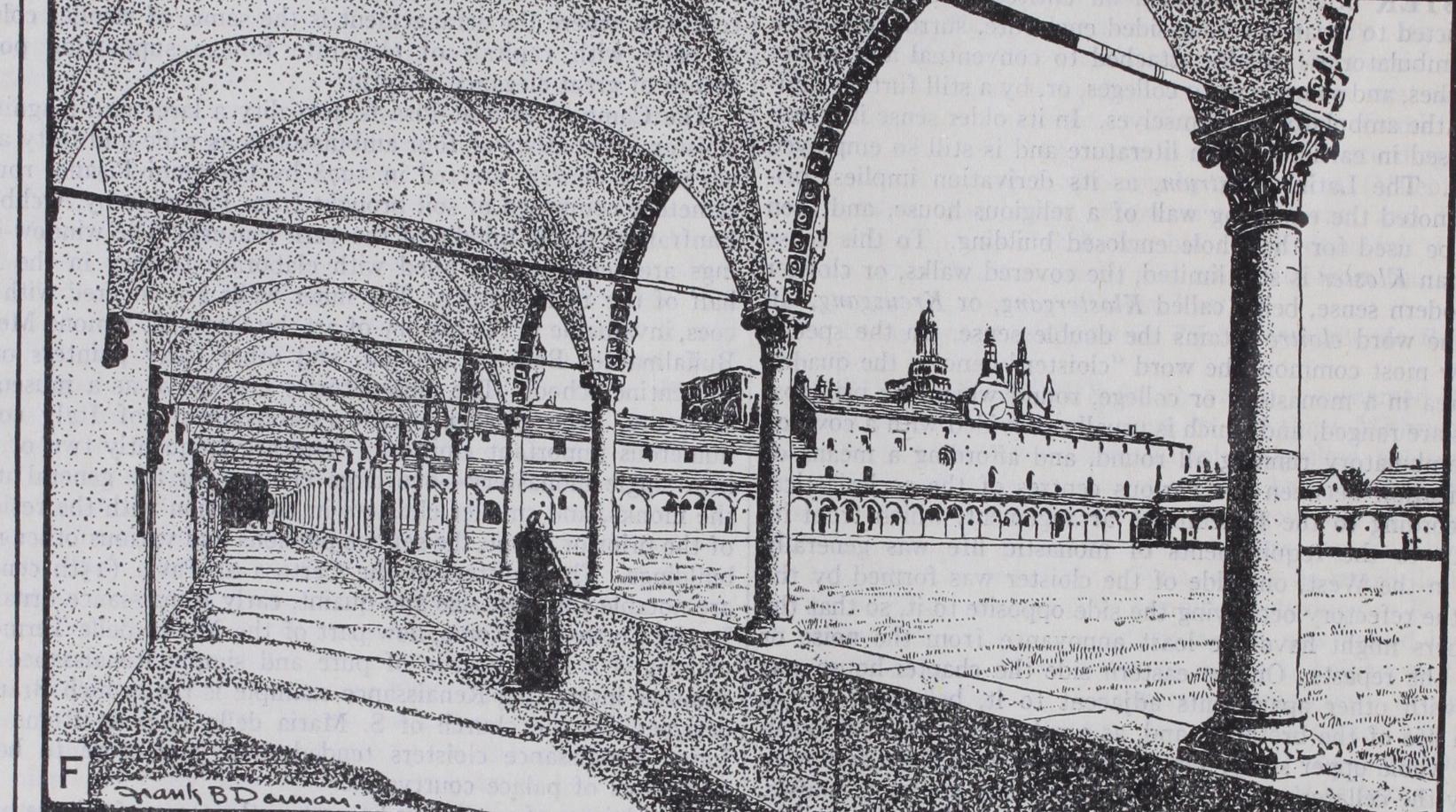

The Campo Santo at Pisa is in reality a large and magnificent cloister. It consists of four ambulatories as wide and lofty as the nave of a church, erected in 1278 by Giovanni Pisano, round a cemetery composed of soil brought from Palestine by Archbishop Lanfranchi in the middle of the Lath century. The window-open ings are semicircular, filled with elaborate tracery in the latter half of the 15th century. The inner walls are covered with fres coes, invaluable in the history of art, by Orcagna, Simone Memmi, Buffalmacco, Benozzo Gozzoli, and other early painters of the Florentine school. The ambulatories now serve as a museum of sculpture. The great monastic establishments of Italy contain numerous important cloisters ; there are frequently two or three in a single monastery—one large cloister for the general use of the monks, and smaller cloisters in connection with the residence of the prior or abbot, the service portions and various other minor buildings. The cloisters at the Certosa at Pavia (I 5th century) are notable for their size and quaint, early Renaissance ornament. In the Certosa at Rome, now part of the Muse° delle Terme, the cloister is a large arcade of pure and simple Renaissance type. Another interesting Renaissance example is that which Bramante designed for the church of S. Maria della Pace at Rome 1504. Later Renaissance cloisters tended more and more to become duplicates of palace courtyards.

The cloister of a religious house was the scene of a large part of the life of its inmates. It was the place of education for the younger members, and of study for the elders. A canon of the Roman council of 826 enjoins the erection of a cloister as an essential portion of an ecclesiastical establishment for the better discipline and instruction of the clerks. Peter of Blois describes schools for the novices as being in the west walk, moral lectures being delivered in that next the church. At Canterbury the monks' school was in the western ambulatory, and it was there that the novices were taught at Durham (Willis, Monastic Build ings of Canterbury, p. 44 ; Rites of Durham, p. . The other alleys, especially that next the church, were devoted to the studies of the elder monks. The constitutions of Hildemar and Dunstan enact that between the church service the brethren should sit in the cloister and read theology. For this purpose small studies, known as "carrols," i.e., a ring or enclosed space, were often found in the recesses of the windows. Of this arrangement there are examples at Gloucester and Chester. The use of these studies is thus described in the Rites of Durham: "In every wyndowe" in the north alley "were iii. pewes or carrells, where every one of the olde monkes had his carrell severally by himself e, that when they had dyned they dyd resorte to that place of cloister, and there studyed upon their books, every one in his carrell all the afternonne unto evensong tyme. This was there exercise every daie." On the opposite wall were cupboards full of books for the use of the students. The cloister arrangements at Canterbury were similar. New studies were made by Prior De Estria in and Prior Selling (1 47 2-94) glazed the south alley, and con structed "the new framed contrivances, of late styled carrols" (Willis, Mon. Buildings, p. 45 )• The cloisters were used also for recreation. The constitutions of Archbishop Lanfranc, sec. 3, permitted the brethren to converse together there at certain hours. To maintain discipline a special officer was appointed under the title of prior claustri. The cloister was furnished with a stone bench running along the side. It was also provided with a lavatory, usually adjacent to the refectory, but sometimes standing in the central area termed the cloister garth, as at Durham. The cloister-garth was used as a place of sepulture, as well as the surrounding alleys. The cloister was in some few instances of two stories, as at Old St. Paul's and St. Stephen's chapel, Westminster, and occasionally, as at Wells, Chi chester and Hereford, had only three alleys, there being no ambu latory under the church wall.

The larger monastic establishments had more than one cloister; there was usually a second connected with the infirmary, of which there are examples at Westminster Abbey and at Canterbury; and sometimes one giving access to the kitchen and other domestic offices. The cloister was not an appendage of monastic houses exclusively. It was also attached to colleges of secular canons, as at the cathedrals of Lincoln, Salisbury, Wells, Hereford and Chi chester, and formerly at St. Paul's and Exeter. A cloister forms an essential part of the colleges of Eton and Winchester, and of New college and Magdalen at Oxford. These were used for reli gious processions and lectures, and for places of exercise for the inmates generally in wet weather, as well as in some instances for sepulture.