Closed Shop

CLOSED SHOP. A closed shop, in America, is a shop in which trade-union members refuse to allow non-unionists to obtain permanent employment. Shops in which non-unionists are permitted are "open shops." Since 1905 trade-unionists have seriously objected to the use of the term "closed shop." Their contention is that its adoption was due to designing employers aiming to place upon unions the onus of persisting in a policy of arbitrary exclusion. Trade-unions have urged that "union shop" (the English phrase) is the proper descriptive term. Curiously enough both the term closed shop, and its opposite, open shop, have to-day meanings altogether different from their original significance. In the early period of American trade-unions a shop employing exclusively union workmen or observing trade-union rules was regarded as open, one not so restricted a closed shop. Af ter 1889 a reversion of these definitions came into usage.

An Old Institution.—The closed shop is not a development of modern industry. Mediaeval British gilds prevented the work ing of non-members ; so also did, when possible, the eighteenth century trade clubs. Some of the gild regulations of the 16th and 17th centuries decreed that no gild journeyman was to work with a non-member : such principles were an integral part of mediaeval society. These tactics were continued by British trade-unionism and were naturally conveyed to America. The Cordwainers' Society of the City of New York in 1804, the New York Typographical Society in 1809 and subsequently other unions adopted by-laws forbidding members to work for employ ers hiring men who did not belong to their organizations or who worked for wages lower than the union scale. The chief weapon used by employers until 1836 was the invoking of old laws de claring combinations of workmen and strikes criminal conspira cies. By about the year 184o the closed-shop rule had been adopted by the majority of American trade-unions, which refused to work with non-union men. These were stigmatized after as "rats" or "scabs." With the repeal or nullification of con spiracy statutes, employers formed local associations to resist the closed-shop movement.

The Trade-Union Label.—This was a powerful influence by which the American unions gained public support for the closed shop of ter the year 1880. Agitating for the abolition of sweat shops, the unions, led by the Cigar Makers' Association of the Pacific coast, succeeded in identifying in the public mind the non union shop with unwholesome conditions productive of disease. Union propaganda along this line increasingly turned consumers against the purchase of articles not made in union establishments and not bearing the union label. Since 190o newer laws and the modernizing of many factories have generally caused the abolition of former bad conditions of manufacture. Trade-unions, how ever, still regard public approval of the union label as pre eminently essential in their campaign for the union or closed shop. This was shown at the 1926 convention of the American Federation of Labor when the union label trades department re ported that by moving pictures and other means it was carrying on an educational campaign which included 36 American States, various Canadian provinces and 396 cities in the United States and Canada.

National Associations Against National Unions.—From 1870 in the United States local trade-unions gradually merged into national unions, the majority of which made the maintenance of the closed shop a vital rule. During the same period, especially in the decade before 1901, there were formed national associa tions of employers, one of the purposes of which was to maintain the open shop. Large factories locked out union men for demand ing the closed shop; the Birmingham Rolling Mill Company did so in 1884; the Granite Manufacturers' Association of Boston in 1887 ; and the Carnegie Steel Company in 1892. The American Federation of Labor declared in 1890 that the working of union with non-union men was inconsistent, especially when union men displaced unionists locked out or engaged in strike. From 185o to 1898 the major part of more than a dozen court decisions held that strikes for the closed shop were criminal or tortious. These decisions had no effect upon trade-union insistence for the closed shop.

Conflicts Over "Closed-Shop" Demands.—The struggle over the closed-shop question reached an intense stage in about the year 1901 when the unions insisted upon employers signing written agreements conceding the closed shop. Previously the granting of the closed shop had been based upon custom or oral negotiation. Declaring that they would not admit "union dicta tion in the management of business," the National Metal Trades Federation and other large employers' associations aggressively campaigned to destroy the closed-shop system.

The award of the anthracite coal strike commission in the great coal strike of 1902 was of most considerable moral help to manu facturers' associations; the commission granted practically every demand of the union except that for the closed shop. Encouraged by this stand, the National Association of Manufacturers in 1902 began a vigorous movement for the open shop. The Citizens' In dustrial Association of America, various citizens' alliances in different cities and a number of large corporations did likewise. The American Federation of Labor reiterated that the trade-union movement stood for the strictly union shop. Union of ter union endorsed the closed-shop principle. The proportion of strikes for recognition of trade-unions and union rules more than trebled in succeeding years. By reducing employment, the panic of 1907 weakened the trade-unions and gave corresponding advantage to employers. The campaigns carried on by the manufacturers' associations also caused a decided shift in public sentiment in favour of the open shop. By 1910 this was established in many industries, notably those which had been consolidated into power ful corporations. The open shop prevailed generally in the South.

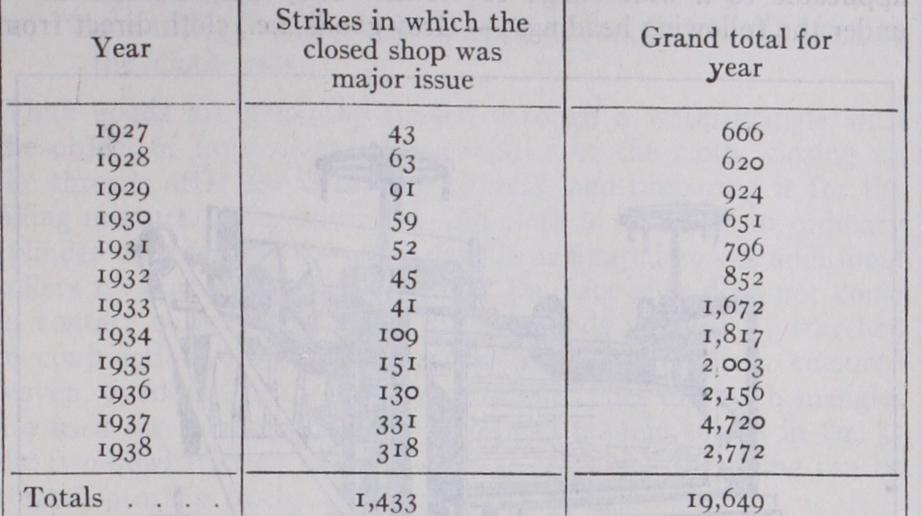

The Company Union.

The entry of the United States into the World War in 1917 brought about auspicious conditions for organized labour in abundant employment and high wages. The power of trade-unions seemed secure. But a formidable rival came into existence to thwart the closed-shop plan. This new factor was the formation of company unions entirely distinct from the regular trade-unions. Company unions are those limited to the workers of a particular corporation and are organized under the auspices of the corporation. Some company unions have existed for more than a quarter of a century but only as isolated, uninfluential bodies. The noteworthy impetus to their widespread creation came in 1918-19, after which they increased rapidly. The statement was made at the 1926 convention of the American Federation of Labor that the number of wage-earners working under company unions' shop management was more than 2,000,000. The National Association of Manufacturers in 1927 computed the real figure at not more than 1,800,00o and possibly as low as 1,5oo,000. The American Federation of Labor numbers 2,800,000 ; the total trade-union organization, including the Rail road Brotherhoods, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers and the Industrial Workers of the World, was in 1927 perhaps 3,700,000. See COMPANY UNIONS.Much of the discussion at the American Federation of Labor's conventions in 1926 and 1927 was concerned with the matter of company unions. Resolution No. 66 in 1926 declared that the open-shop forces, under the leadership of various associated em ployers' associations, had organized dual and company unions. These, the resolution held, were artificial creations, and as a menace to the trade-union movement they must be overcome. Voluntary trade-union management co-operating with employers was suggested as a substitute for company unions controlled by employers. Delegates assailed the "so-called and misnamed American plan" as an un-American one by which employers de liberately sought to bring about industrial serfdom denying free dom of contract and right of choice. In its report to the 1927 convention the executive council of the American Federation of Labor defined the company union as an element which did not make standards; "it is an agency for administering the affairs of a company and is not an economic and social force." Status of the Closed Shop.—Reports of the U.S. bureau of labour statistics show that strikes for the closed or against the open shop have been increasing in recent years; of 17,994 labour disputes from 1918 to 1925 inclusive, only 483 dealt with the closed or open shop. However, from 1927 to 1938 inclusive, of 19,649 labour disputes, dealt with the closed or open shop.

Strikes in Which the Closed Shop Was the Major Issue, 1927-38 Compiled from the Monthly Labor Review, May 1937, Table 8, May 1938, Table 10, and May 1939, Table 1o; also, Strikes in the United States, 1880-1936, Bulletin No. 651, United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, Table 28.