Coal Electrical Power Uses Coal Carbonization

COAL; ELECTRICAL POWER USES; COAL CARBONIZATION The use to which a coal can be most profitably put depends on two factors, its chemical composition and its physical character. A coal may have a high fixed carbon content, and as such may be capable of giving out great heat, but owing to its low volatile hydrocarbon content prove useless as a steam-raising coal except under forced draught. Again the ash content in an otherwise per fect steam coal may be so high as to render it a costly coal to use ; or its ash may be fusible at a comparatively low temperature, and so choke the firebars with clinkers; or the sulphur content may be so high as to prove a destructive element especially in the case of a water-tubular boiler ; or a coal may be excellent in point of chemical analysis, but is so friable that it breaks up in transport and cannot be burnt except in a pulverized form for raising steam, and must be used for making coke, patent fuel, or as pulverized coal. But as to making coal into coke, all coals are not possessed of the caking property, a quality which probably depends on physical as well as chemical characteristics. (See Section I.) Characteristics.—The most important class of coals is that commonly known as "bituminous" from their property of soften ing or undergoing an apparent fusion when heated to a tempera ture far below that at which actual combustion takes place. This term is founded on a misapprehension of the nature of the occur rence, since, although the softening takes place at a low tempera ture, still it marks the point at which destructive distillation com mences and hydrocarbons, both of a solid and gaseous character, are formed. That nothing analogous to bitumen exists in coals is proved by the fact that the ordinary solvents for bituminous sub stances, such as bisulphide of carbon and benzol, have no effect upon them, as would be the case if they contained bitumen soluble in these reagents. The term is, however, a convenient one, and one the use of which is almost a necessity, from its having an almost universal currency among those connected with coal and coal mining.

Variations in composition are attended with corresponding dif ferences in qualities, which are distinguished by special names. Thus the semi-anthracitic coals of South Wales are known as "dry steam coals," and when still less anthracitic are known simply as "steam coals," being especially valuable for use in marine steam boilers, as they burn more readily than anthracite and with a larger amount of flame, while giving out a great amount of heat, and practically without producing smoke. Coals richer in hy drogen, on the other hand, are more useful for burning in open fires,—smiths' forges and furnaces,—where a long flame is required.

The excess of hydrogen in a coal above the amount necessary to combine with its oxygen to form water, is known as "dispos able" hydrogen, and is a measure of the fitness of the coal for use in gas-making. This excess is greatest in what is known as cannel coal, the Lancashire kennel or candle coal, so named from the bright light it gives out when burning. This, although of very small value as fuel, commands a specially high price for gas making. Cannel is more compact and duller than ordinary coal and can be wrought in the lathe and polished. These properties are most highly developed in the substance known as jet, which is a variety of cannel found in the lower oolitic strata of Yorkshire, and is almost entirely used for ornamental purposes, the whole quantity produced near Whitby, together with a further supply from Spain, being manufactured into articles of jewellery at that town.

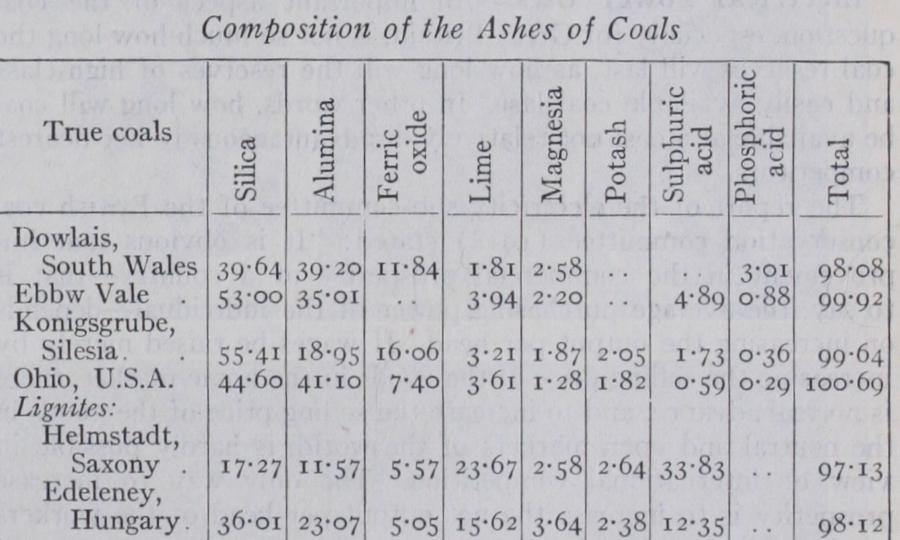

By the term "ash" is understood the mineral matter remaining unconsumed after the complete combustion of the carbonaceous portion of a coal. According to Couriot (Annales de la Societe geologique de Belgique, vol. xxiii., p. ios) the stratified character of the ash may be rendered apparent in an X-ray photograph of a piece of coal about an inch thick, when it appears in thin parallel bands, the combustible portion remaining transparent. It may also be rendered visible if a smooth block of free-burning coal is allowed to burn away quickly in an open fire, when the ash re mains in thin grey or yellow bands on the surface of the block. The composition of the ashes of different coals is subject to con siderable variation, as will be seen by the table below :— The composition of the ash of true coal approximates to that of a fire-clay, allowance being made for lime, which may be pres ent either as carbonate or sulphate, and for sulphuric acid. Sul phur is derived mainly from iron pyrites, which yield sulphates by combustion. An indication of the character of the ash of a coal is afforded by its colour, white ash coals generally being freer from sulphur than those containing iron pyrites, which yield a red ash. There are, however, several striking exceptions, as for instance in the anthracite from Peru, which contains more than of sulphur, and yields but a very small percentage of a white ash. In this coal, as well as in the lignite of Tasmania, known as white coal or Tasmanite, the sulphur occurs in organic combina tion, but is so firmly held that it can only be very partially ex pelled, even by exposure to a very high and continued heating out of contact with the air. An anthracite occurring in connection with the old volcanic rocks of Arthur's Seat, Edinburgh, which con tains a large amount of sulphur in proportion to the ash, has been found to behave in a similar manner. Under ordinary condi tions, from to a of the whole amount of sulphur in a coal is removed during combustion, the remaining a to $ being found in the ash.

The amount of water present in freshly raised coals varies very considerably. It is generally largest in lignites, which may some times contain 3o% or even more, while in the coals of the Coal Measures, it does not usually exceed from 5% to io%. The loss in weight by exposure to the atmosphere from drying may be from 2 to a of the total amount of water contained.

When coal is heated to redness out of contact with the air, the more volatile constituents, water, hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen, are in great part expelled, a portion of the carbon being also vol atilized in the form of hydrocarbons and carbonic oxide, the greater part, however, remaining behind, together with all the min eral matter. or ash, in the form of coke, or, as it is also called, "fixed carbon." The proportion of this residue is greatest in the more anthracitic or drier coals, but a more valuable product is yielded by those richer in hydrogen. Very important distinctions —those of caking or non-caking—are founded on the behaviour of coals when subjected to the process of coking. The former class undergo an incipient fusion or softening when heated, so that the fragments coalesce and yield a compact coke, while the latter (also called free-burning) preserve their form, producing a coke which is only serviceable when made from large pieces of coal, the smaller pieces being incoherent and of no value. The caking property is best developed in coals low in oxygen with 25 to 3o% of volatile matters. As a matter of experience, it is found that caking coals lose that property when exposed to the action of the air for a lengthened period, or by heating to about 300° C, and that the dust or slack of non-caking coal may, in some instances, be con verted into a coherent coke by exposing it suddenly to a very high temperature, or compressing it strongly before charging it into the oven. From the chemical point of view it might appear that the quantity of hydrogen is a governing factor in determining the cok ability of a coal, for an otherwise non-coking coal can be made to coke by adding to it a very small percentage of hydrogen. (See also COKE.) Electrical Power Uses.—An important aspect of the coal question, especially for Great Britain, is not so much how long the coal reserves will last, as how long will the reserves of high-class and easily available coal last. In other words, how long will coal be available at a cost not relatively disadvantageous to her nearest competitors.

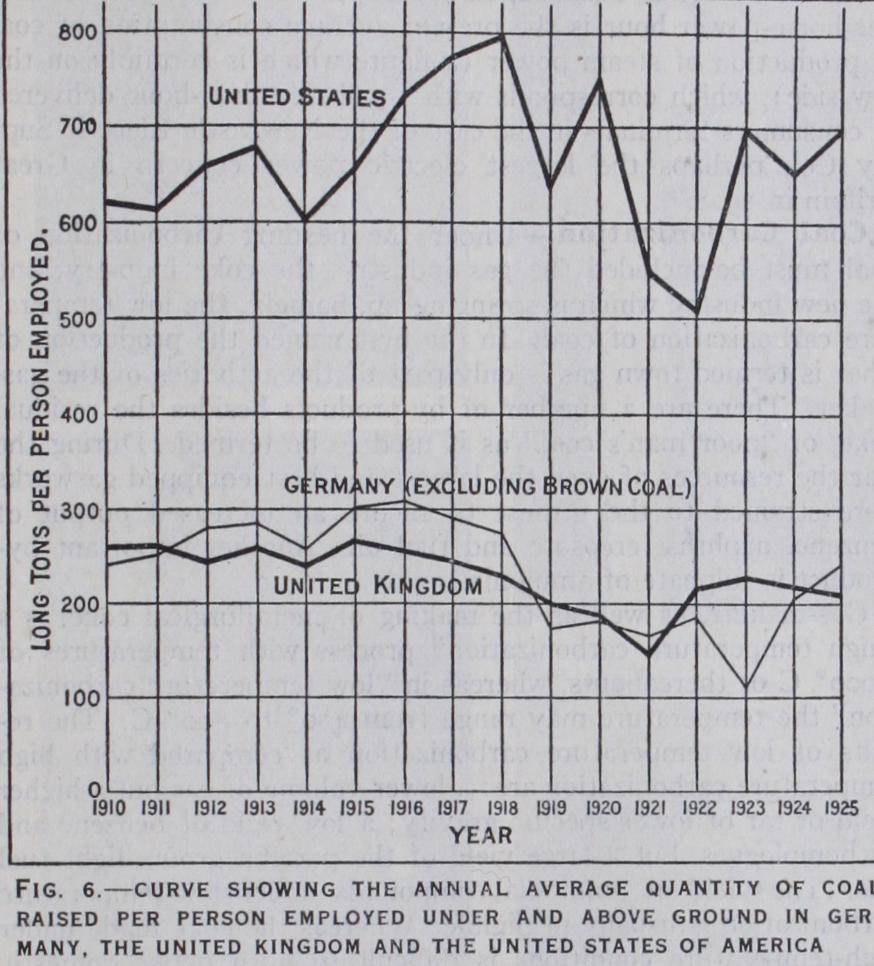

The report of the electricity sub-committee of the British coal conservation committee (1918) stated : "It is obvious that im provement in the commercial prosperity of a country—that is to say, the average purchasing power of the individual—depends on increasing the output per head. If wages be raised merely by increasing the selling price of the goods in the home market, there is no real advance, and to increase the selling price of the goods in the neutral and open markets of the world, is hardly possible in view of international competition. The only way to increase prosperity is to increase the net output per head of the workers employed." In the United States of America the amount of power used per worker is 56% more than in the United Kingdom; and the best cure for low wages is more motive power. It has been settled con clusively of late years that the most economical means of applying power to industry is the electric motor, that is, as the means of applying the power which may have been generated by any form of prime mover (water, steam, gas or oil). In Great Britain the water power is negligible and the oil nil, so the problem resolves it self into the most economical production of electric power from coal.

It has been calculated from the data available in the British census of production, and making certain necessary adjustments, that—excluding the horse-power used at blast furnaces, gas works, etc., since the coal consumed in these industries is ex cluded from the estimate of coal consumption in industry—the total capacity of engines, i.e., steam reciprocating, steam turbine, internal combustion, water power, and other power, in use was h.p., of which 91.2% was in respect of steam, 6.4% " " " " internal combustion, 1.7% " " " " water power, o.7% " " " " other power.

It has been estimated, too (see report of the coal conservation committee), that were a complete system of electrification inaug urated in Great Britain, on the basis of the extent to which power is used at present, a saving of 55,000,000 tons of coal per annum might be effected, resulting in a saving of L27,500,000 (valuing the coal at only los. per ton), while if the coal were used for ex tended and new industrial purposes, some 15,000,000 h.p. would be continuously available for the purpose throughout the year.

This estimate is based upon the supposition that 71b. of coal per horse-power hour is the present average consumption of coal in production of steam power (a figure which is certainly on the low side), which corresponds with I•541b. per h.p.-hour delivered at consumers terminals in the case of the Newcastle Electric Sup ply Co., perhaps the largest electric power concern in Great Britain in 1928.

Coal Carbonization.

Under the heading carbonization of coal must be included the gas industry, the coke industry, and the new industry which is springing up, namely, the low tempera ture carbonization of coal. In the first named the production of what is termed town gas is only part of the activities of the gas maker. There are a number of by-products besides the residual coke, or "poor man's coal" as it used to be termed. During the war the resources of even the largest and best equipped gasworks were strained to the utmost to secure an increased output of benzene, naphtha, creosote and fuel oil. Another important by product is sulphate of ammonia.Gas-making, as well as the making of metallurgical coke, is a "high temperature carbonization" process with temperatures of I,000° C or thereabouts, whereas in "low temperature carboniza tion" the temperature may range from 400° to 800° C. The re sults of low temperature carbonization as compared with high temperature carbonization are : a lower volume of gas but a higher yield of tar of lower specific gravity; a low yield of benzene and its homologues, but a large yield of the paraffin group, light fuel oils. The yield of ammonia compounds under low-temperature carbonization is usually negligible. Whereas the coke made under high-temperature conditions is difficult to burn under domestic conditions in Great Britain, being chiefly usable for metallurgical purposes; that yielded by low-temperature carbonization is an excellent household fuel containing as it does from 6 to 12% of volatile hydrocarbons. (See also Section VII. and the articles