Coal Industry United States

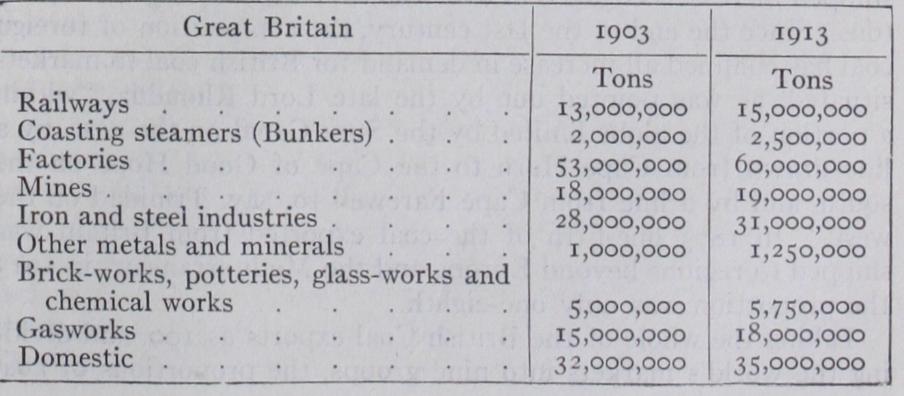

COAL INDUSTRY: UNITED STATES According to recent estimates, those of the International Geological Congress, the United States has about 52% of the coal supply of the world, but in view of the fact that the geological resources are probably almost as closely estimated in the United States as in any part of the globe and that large areas of the earth's surface have been only roughly surveyed and some not at all, this figure may be subject to some reduction. Twenty-eight States, as well as the Territory of Alaska and the Philippine islands, have bountiful supplies of coal, 8 States have only a small quantity in each and 12 States, with the Hawaiian islands, are absolutely without this fuel. Table I. shows the separate produc tion of 25 states and Alaska in 1926 with the combined tonnage of Arizona, California, Idaho, Nebraska, Nevada and Oregon.

Some of the figures in the last column of the table—"average tons per man per day"—may be too high in some States because men in those regions frequently go into the mines to shoot coal and load cars on days when the tipples or mines as a whole are not in operation. The figures relate only to active mines of com mercial size that produced bituminous coal in 1937. The number of such mines in the United States was 6,548 in 1937, 6,057 in 1929 and 9,331 in 1923. There were 212 mines in Class IA (pro ducing soo,000 tons or over in the course of the year). These mined 13 7.6 % of the entire tonnage. There were 449 in Class 1 B (with a tonnage between 200,000 and soo,000). These produced 31.2 % of the tonnage. Class 2 (I00,00o to 200,000 tons) num bered 469 and produced % ; Class 3 (so,000 to ioo,000 tons) numbered 448 and produced 7.4%; Class 4 (io,000 to 50,000 tons) numbered 1,117 and produced 5.8% and Class 5 (less than tons) numbered 3,853 and produced 2.6%. Two important trends disclosed by Table I are a marked reduction in the amounts of fuel used by the mines, and a heavy increase in shipments by truck. The general development of truck transportation has re sulted in truck shipments over a considerable area, instead of only for purely local sales.

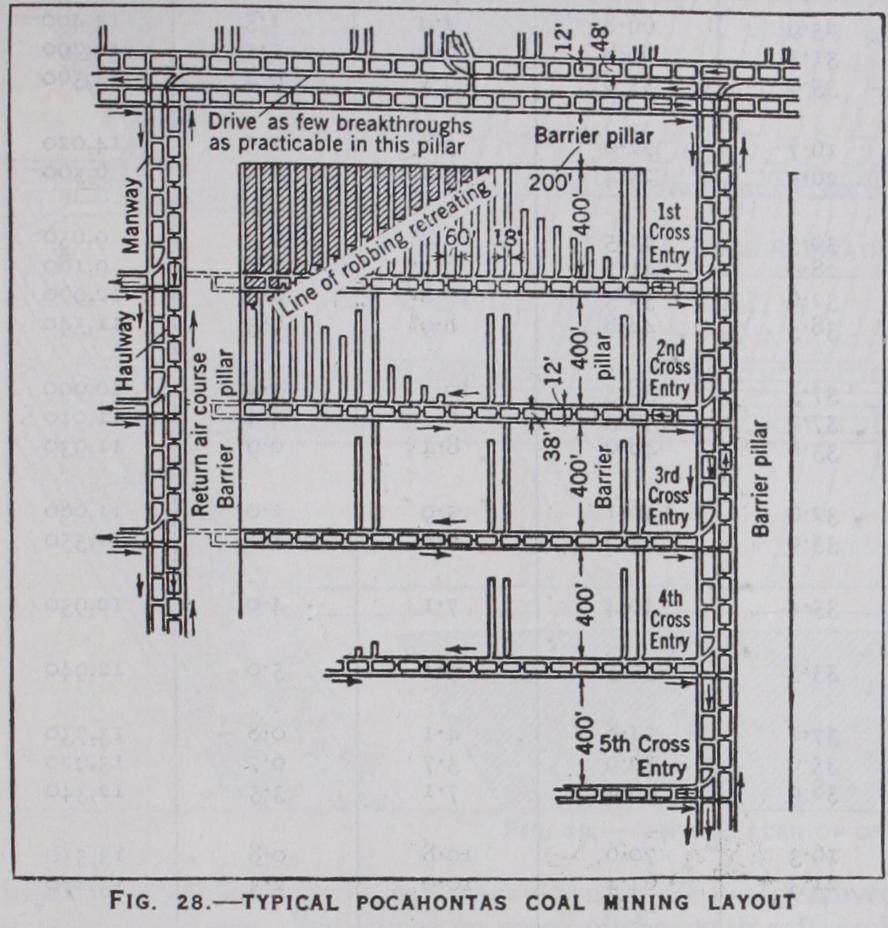

Table II. shows the coal analyses in more important districts. Pennsylvania Anthracite.—The anthracite region of Penn sylvania until and including 1869 (except in 1865) produced more coal than all the rest of the United States. In that year the output of Pennsylvania anthracite was tons. Since that time the tonnage of the anthracite field has increased, but the production of bituminous coal and lignite has augmented so much more rapidly that in 1938 the anthracite tonnage was only I 1.8% of the total. (See ANTHRACITE.) Methods of Mining.—Most of the coal produced in the United States is mined by room-and-pillar methods which are equivalent to the bord-and-pillar, or post-and-stall, methods of Great Britain. The width of the room varies from io to 8o ft. depending on the strength of the part of the roof immediately over the coal, the depth of the seam from the surface, whether it is the purpose to withdraw the pillar and whether an attempt is made not to disturb the surface. Where, as in the Connellsville region of Pennsylvania, the cover is deep and the pillar coal friable, the room width may be only 12 ft. wide, especially, if, as is usual, the extraction of the pillar or "second mining" is to be attempted later. In that case pillars of as much as 8o ft. width have been provided. In many parts of West Virginia, in central and southern Illinois, and in the south-western coal region generally where pillars are not removed, the percentage of recovery may be less than 5o. In the Connellsville, Fairmont and Pocahontas regions complete extraction is attempted and 9o% is frequently attained. In these regions the pillars are withdrawn retreating and in a long break line extending over two or three entries which is adhered to rigidly in order that no pillar may form a salient angle in the line of goaf, and thus receive more than its due load. No coal is left standing. If it cannot be loaded it must, at least, be shot down so as to permit the roof to break and fall, relieving the stress on the coal face. In such instances the roof is frequently observed to be torn on the surface, as in longwall workings, some hundreds of feet back of the break line over the still standing coal. The underground breaks of the roof within the area that has been totally excavated doubtless do not connect with these surface breaks. The fractures in the workings appear to project into the goaf, or excavated area, from a line near the break line at an angle to the horizontal of 7o degrees, leaving a corbel of rock along the break line.

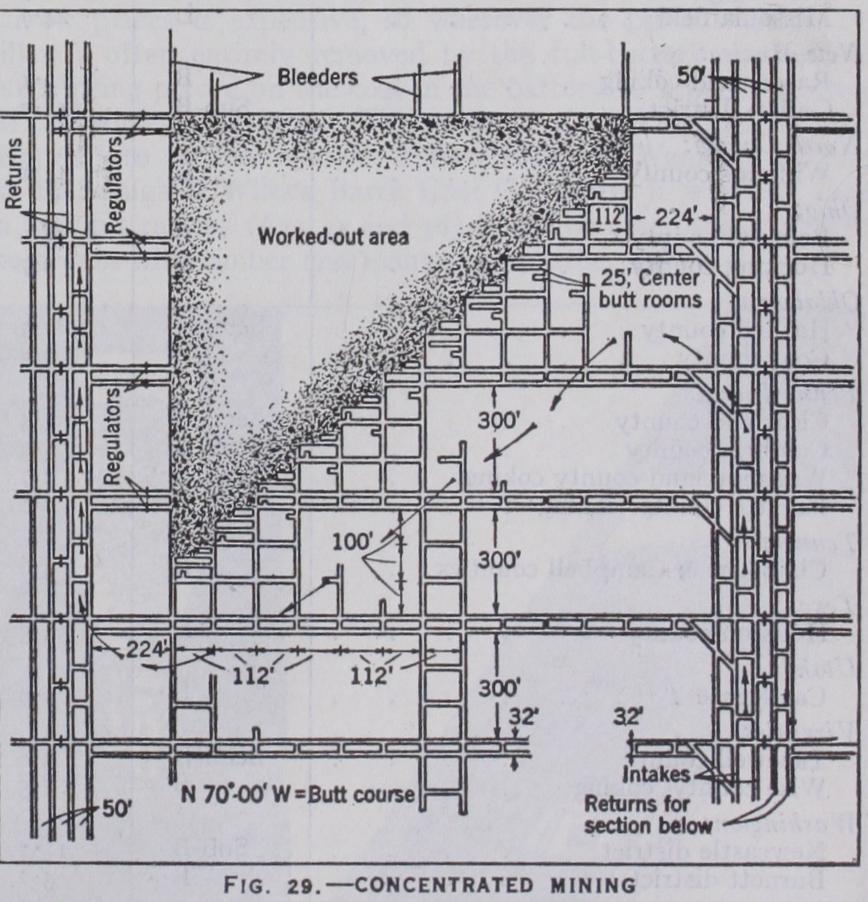

Plans (fig. 28) are shown or a standard practice of mining in the Pocahontas region from an article by Audley H. Stow in Coal Age, vol. 3, pp. Another (fig. 3o) of the methods of operation of the U.S. Coal and Coke Co. is from an article by Edward O'Toole on the Poca hontas Coal Field, Trans. A.I.M.E., vol. lxxii., pp. 874-897. The plan of concentrated mining of the H. C. Frick Coke Co. and others (fig. 29) is derived from Trans. A.I.M.E. vol. lxxiv. pp. Longwall of the circular advancing type has been in operation for many years in northern Illinois, northern Iowa and northern Missouri, also in parts of Arkansas. In general it was adopted only where, as the coal was thin, packwall material was available. Only in quite recent years with the advent of conveyors has longwall been adopted where the coal is of such thickness that rooms can be driven without lifting bottom or shooting top rock and even then but seldom. Room-and-pillar is still standard and almost universal practice where the coal thickness exceeds 4 feet.

Mine Gradients.

In southern Illinois the coal is as level as the prairie land above it, and in much of the United States it is on gradients running from zero to 5%. As the great Appalachian uplift is reached on the east and the Cascades are approached on the west the grades increase. The gentle folds of western Pennsyl vania give way to steeper folds in the central Pennsylvania area, grades of io% being not uncommon. In the anthracite region the coal may pitch at 90 degrees and even turn over so that the rock that was laid down as the roof of the coal becomes what metal miners term the footwall. In the Cahaba and Coosa regions of Alabama, similar conditions exist and in the Cascades also.There are between the Appalachians and the Cascades some heavy gradients. In Wyoming at Hanna, Gebo, Cumberland, Kemmerer and Rock Springs they have given much trouble. At first it was customary to drive the rooms up the pitch and let the loads pull the empties up to the face of the room, a rope pass ing over a pulley connecting the two. Friction in some cases had to be used to steady the loads down the grade, and, wood rails being used, speed of travel was further reduced. This method resulted in many accidents to cars and to men. Derailments were frequent, so the method was discontinued at Hanna, Gebo and Rock Springs. In Alabama this system is still being used. In Wyoming it became the custom to drive engine planes down the dip and lay out the rooms on the strike. The loaded cars are drawn by mules to the room mouth and there a rope is attached, the cars being pulled one by one by this rope around the switch or room parting up the engine plane to the level heading above. There the cars from the various rooms are assembled and pulled by electric locomotives to the main hoist. The mining machines are also lowered or raised on the same engine plane to the rooms which are to be cut. This involves four haulage units—mule, small hoist, locomotive and main hoist—and this does not make for efficiency but the plan seems to be better than the old method. More re cently, with the advent of conveyors and scrapers, it has become general practice once again to drive rooms and, sometimes, long faces directly up the pitch, bringing the coal down to level gang ways, from which it is hauled by electric locomotives to engine planes, on which it is hoisted to the surface.

Steep grades are also found in Colorado, and in northern Illi nois is an extremely steep inclination in a coal bed near La Salle, but this coal is not being mined where the pitch occurs.

Steep Gradient Methods.

Where the pitches are heavy in deed but still light enough for the purpose, it has been customary in the anthracite region to use what is known as a "buggy breast" (fig. 31). The breast or room, is driven up the pitch, and rock is piled in the roadway near the mouth of the room to a considerable depth and to a gradually decreasing depth toward the face so as to reduce the gradient. On the new inclination thus formed a small car or "buggy" is run. This is dumped at the end of the grade into a short chute which carries the coal to a point near the entry where it can be loaded into a standard mine car. The system is used on gradients from 10 to 18 degrees. On lesser gradients thy room is frequently turned enough off the pitch to make it possible to place the standard car at the face by mule power or electric motor.Where the pitch runs from i8 to 3o degrees, sheet iron is used. Where the coal will not run it has to be pushed or "bucked" with a shovel at great expenditure of human energy. When the coal runs too freely the sheet iron can be omitted and boards laid or the coal may be allowed to run on the coal floor. But with heavier grades the full-battery system is used (figs. 32 and 33). A heavy battery or barricade is erected somewhere, either at the mouth of the room or further in. A chute with a gate at the barricade leads to the car. The coal as it is dislodged is directed to the centre of the room, where it is held by two lines of posts and tim ber on either side of the centre. It is allowed to fill this space.

On either side is a manway which is kept open. Any excess of coal over that needed to fill the battery is let out through the gate and loaded into cars on the gangway by gravity. The rest of the coal is not loaded till the room or "chute" is driven its full distance up the pitch.

In early days pillars were not drawn. To-day long holes are drilled in the pillar and the coal shot down or the coal removed in some other way. Sometimes on steep pitches with soft coal, such as the Primrose, the coal will run out of the bed and a steady flow can be taken out at the gate till the roof falls and rock ap on a slope much less than that of the full pitch (Trans. A.LIVLE. vol. pp- The pillars between breasts, whether level or pitching steeply, are often "skipped" (that is, reduced in size by taking off a part up one side) or split by a roadway where the coal pitches slightly or by what is known as a "chute" if the coal pitches heavily. After this the pillar is brought back, but in any event driving these narrow places is expensive, so wherever the pitch is steep the pillar is often entirely removed by the full-battery method, re liance being placed on the coal in the battery to support the roof till the pillar is extracted. This manner of working has been de veloped into another system, known after the Wanamie Colliery of the Lehigh & Wilkes Barre Coal Co. where it was first used. In the illustrations (figs. 35 and 36) it will be noted that "breasts" are driven with timber and rnanways on either side.

FIG. 31.-BUGGY BREAST ON 10-18 DEGREE PITCHFig. 31.-BUGGY BREAST ON 10-18 DEGREE PITCH pears. The objection to the full-battery system lies in the "deg radation," or breaking, of the coal to small sizes and the delay in getting the benefit of a large part of the coal won. In conse quence new systems are being put in operation in the anthracite region, notably the slant chute system (fig. 34) used first on a heavy pitch in No. i tunnel of the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Co., which, as will be seen, shortens the distance the coal has to travel on the full pitch, arranges for the removal of all the coal and provides that the coal will travel the greater part of the distance The Carbon Hill Coal Co. is using what is practically "tallies chassantes," or a stepped longwall face travelling along the pitch in a level direction, the upper end trailing behind the lower, see fig. 39. Each miner has his own step, below which is set a wood planking termed a "wing" which protects the miner below and directs the coal to a chute which carries the coal to a gangway below.

Where in this state badly split seams have to be worked on a steep pitch even more elaborate methods are used. For further de tails of the methods described and others see Simon H. Ash in the Trans. A.I.M.E., vol. lxxii., pp. Fig. 35 shows the Wanamie method of removing pillars upward from the chain pillar by use of the full battery. Fig. 36 exhibits the means by which the uprise is constructed through the chain pillar. In fig. 37 is illustrated the manner in which, in Pierce County, Washington, narrow "chutes," or rooms, are extended to be drawn back as shown in fig. 38. A longwall method used by the Carbon Hill Coal Co. in Washington is outlined in fig. 39. In many anthracite mines, where pillars have been left in one seam and another seam below it is worked later, rockholes are driven vertically or at a steep angle up to the pillar of the first seam, in which a narrow place is driven till another narrow place is reached from another rockhole. Thus ventilation is provided and the pillar is removed, the coal being dropped or chuted down the rockhole. Much coal in the Mammoth is thus being recovered through the Skidmore bed and the Big Ross through the Little Ross.

Cutters.---Only

a few industries in the United States have made equal progress with coal mining in the present century.when shot with scarcely any change in condition. In conse quence "snubbing," or converting the uniform kerf into one of wedge shape, is a quite general practice. This work has been done mechanically but not in many mines.

The breast machine, which makes a series of forward cuts under the coal, about the width of the machine and has to be retreated and moved each time a cut is made, still continues to be used, not because anyone prefers it but because such equipment is on hand or can be bought second-hand cheaply and because the wage scale for cutting makes usually no distinctions.

The shortwall cutting machine is provided with chains which enable it to sump its cutter bar into the coal. When it has arrived at the required depth it can be caused to travel across the face cutting the kerf as it goes and stopping only when it has traversed the room or entry. The longwall machine can also cut itself into the coal, but is best suited to places where continuous cutting for a long distance is available.

Some cutting machines are mounted on a truck and cut from the rail. They can be adjusted to place a kerf at any desired level. In some mines with fragile roof they cut their kerf near the top of the coal so that the shots can be put near the bot tom. In this case the shots must be heavy or they will be less effective than with undercutting and top shooting. In other cases the cut is made in some impurity which it is desirable to remove. In some mines the machine is caused to cut across the face two or more times to remove completely a thick "binder" or "part ing" which it is desirable to keep out of the coal. Some machines cut a square kerf and others one that is circular. Machines of this type are made which cut both horizontally and vertically, so that having cut the coal with a level kerf they can cut it vertically or "shear" it as the expression runs. This increases the percentage of "cuttings," or "bug dust," but is said on good authority to so greatly lessen the use of powder that less fine coal results. Plate II., fig. 3 shows a shearing machine.

Longwall machines are made of heights as low as i 2 inches. So far no coal is being worked in the United States too low for the operation of a shortwall machine. The track-mounted, or turret, Very little coal is now undercut by hand despite statistics. In some places the law requires the miner to undercut the coal, but unless it is undercut for him by machine he rarely does more than make a cut of a foot or two and then shoots the coal from the solid. The punching machine, whether operated by air directly, or by air compressed at the machine electrically, has almost entirely disappeared. It cut the coal with a wedge-shaped kerf causing it to fall heavily and roll over so that it was easy to load. All other machines make a uniform kerf and the undercut coal may fall machines require greater height and there are fewer of them in use. Disc machines like those so common in Great Britain are unknown in the United States. Post punchers, however, have been used. A shortwall machine with a rotary bar armed with cutter bits has been operated in West Virginia for cutting across faces. The introduction of mechanical cutting has been accompanied by mechanical haulage and mechanical drilling. The horse and mule are units of power well suited for "gathering" cars from rooms and entries where the height of the seam is suitable. They can work in gas without hazard. They can go up one room pulling a car, pass through a crosscut to another room and bring out a loaded car, and they often can go through a crosscut from one entry to another and so work conveniently in both. This "flexi bility" is absent with electrical equipment which, however, has the advantage of being able to bring more and heavier cars to the parting, requires no food when idle, and is not so readily stalled by adverse gradients.

Haulage.

In 1924 (H. O. Rogers, U.S. Bureau of Mines, in Coal Age, vol. 32, pp. 84-88) no less than 36,352 animals were still used for underground haulage in bituminous mines. There were also 649 rope haulages, excluding those on main slopes; 779 storage-battery locomotives that can be run with or without trolley current ; 1,515 storage-battery locomotives without trolley; 11,986 electric trolley locomotives, 85 compressed-air locomotives, 226 gasolene locomotives, 132 steam locomotives, a total of 14,723 and 6 ft. inside width. With such wide cars the sides are flared at a low angle or the bottoms are wider than the gauge and the tops of the wheels run in a housing provided in the flared sides or in the bottom.Coal is often hauled in mines a distance of 5 miles. The H. C. Frick Coke Co. at one point had three shaft mines which were about 4 m. from the Monongahela river, on which lay their Clair ton by-product plant. The three mines were combined under ground; two rotary dumps were installed each capable of over turning forty 2.1-ton mine cars at one time with a feeding device for delivering that quantity of coal to a 6o-in. fabric belt and a series of 18 rubber belts, 48 in. wide, aggregating with the fabric belts 4 m. and 1,810 ft. (Pl. I. fig. 8). The coal is dumped from a cross belt into hoppers over the river, and then into barges.

Another belt line has been built by the same company of a sim ilar character but a little less than 3 m. long with a single 30 wagon underground rotary dump, which delivers the coal that comes from two mines, and a single 2-wagon underground rotary dump which delivers the coal from a third mine. This equip ment has a capacity of 12,80o tons per 8-hour day.

For the haulage of large trains big electric locomotives are provided or units are put in tandem. One large electric locomotive weighs 38 tons and develops 399 h.p. from three 500-volt motors. Storage-battery locomotives, locomotives with a cable reel and crab locomotives with a wire cable which serves as a portable hoist are used for gathering. The first two are those most gener locomotives of all kinds. The percentage of coal hauled by ani mals only in bituminous mines was i o.1 ; by rope only o.i ; by locomotive only 32.8; by animal and rope 1.9; by animals and locomotives 5o.o; by rope and locomotives 1.3; and by animals, rope and locomotive 3.8. This does not include strip-pit coal; 85.6% came from mines using one or more locomotives.

Mine cars are increasing in size, due to the fact that being loaded by machinery the labour of lifting coal to a high car need not be considered, that where large loading machines are provided to get maximum results large receiving units are necessary, that in thin coal a large car can be loaded as readily as a small one, for the loading is done in a high entry, that the haulage units are adequate to handle the biggest cars and that improvements spring-draft rigging, automatic couplings and bearings—are rela tively more economical in weight and cost with a large car. In order to get capacity the body of the car is made wider than the track (which sometimes has as much as 4 ft. 81 in. gauge). Cars are made as large as 12 ft. long over bumpers, 1 o ft. inside length ally used. For gathering on down gradients room hoists are often provided.

Mechanical Loading.

Last of all improvements is mechani cal loading, which in the United States has been liberally inter preted to include both hand-loading into conveyors and loading by machinery into mine cars. Strange to say, the United States had the first conveyor longwall working, namely the Vintondale mine of the Lackawanna Coal Co., in Cambria county, Pennsyl vania. The first installation was made by C. R. Claghorn in 1901. After a change in management the longwall face caved, destroy ing some hundreds of feet of conveyor, and the plan was aban doned, but meantime a large coal area had been worked by this means. Col. Blackett introduced the system into England, and it returned to the United States as a European practice owing to its many years of estrangement. Conveyors are being used in many ways. In some instances they are being operated in rooms 3o to 4o ft. wide. The coal is cut by a machine which is kept in the room and used by the loaders whenever they are ready to prepare the face for shooting. When the coal is shot down part of it—perhaps a third—falls on a cross conveyor which carries it to the main conveyor, in this instance, a shaking pan (Pl. II. fig. 6), which transports it from the face to the entry, where it is discharged into a mine car. Another third perhaps is pulled down onto the cross conveyor and yet another third has to be shovelled. This shovelling is easily performed because the conveyor is every where near the coal and because the coal need be lifted only a clear height of 4 in. instead of, say, 2 feet. The coal need be shovelled only once whereas with two roads in a 4o-ft. room it may be necessary to shovel some of it twice or three times. The cross conveyor consists of a flight conveyor and at the end has what is known as a "gooseneck" which raises the coal a sufficient height to deposit it in the shaking conveyor, into the end of which also some coal falls from the face or is shovelled. Chain-mat con veyors are also used.In other cases the working place has been made ioo ft. or more wide and the coal has been thrown into a shaking conveyor running parallel with the face. This dumps into another shaking conveyor, both conveyors being driven by a common unit, the face conveyor being actuated by the main conveyor through a bell-crank attachment. However, frequently the conveyor is situated in front of a long face which may be level or possibly on a pitch (see fig. 40). Where coal is left along the entry, conveyors may be used to receive the coal near the entry pillar and to convey it to the opening through the pillar. Another conveyor then lifts it into the car. Another provision is the duckbill loader which can be used even where the place being driven is narrow. The dif ferential movement of the shaking conveyor that pitches the coal forward as does a shovel in the hands of a miner is used to enable the duckbill attachment at the end of the shaking conveyor to dig into the coal. As the duckbill has a flaring mouth and wedged teeth it gets under the pile. As soon as the coal is in the shovel like duckbill it is carried back toward the room mouth. By arrang ing for the swiveling of the conveyor it is possible to make the duckbill attachment clear a wide area of coal. Little trimming is necessary. Arrangements are provided for feeding the duckbill forward without stopping the equipment.

By putting another shaking conveyor at right angles to the main conveyor with a bell-crank attachment and by transferring the duckbill to this face conveyor, it is possible to have it load off the end of the pillar of the room. This is a valuable aid to safety as the duckbill needs for its manoeuvring only the space occupied by the cut at the pillar end. The system is illustrated by a drawing from an article by Oscar Cartlidge in Coal Age, vol. xxxiii., p. 473 (see fig. 41). In the West the conveyors in several rooms have been connected with one drive and that also has been done in the anthracite region. Where the pans transmit the motion, each room, perhaps, should have its own drive unit.

Mechanical Scrapers.

Mechanical scrapers were devised by Cadwallader Evans in Jan. 1914. They are well suited' to thin coal and are so used for the most part but they are also used on thick coal. Fig. 42 shows an Illinois application (from Coal Age, vol. xxxi., p. 428, in which the scraper is used advancing. The loading chute is seen at the mouth of the room and in this in stance can be skidded sidewise so as to be available for use in two rooms. The general appearance of a scraper, albeit small, can be noted in Pl. I. fig. 6. The scoop shovels travel on the floor of the mine and pull from 250 lb. to 5 tons. Where, however, the larger size is used the coal is thick and the scraper is hauled along a face 200 or 30o ft. in length. The retreating method (see fig. 43) is quite generally used. A narrow place is driven up the cen tre of what will later be the room and when this has reached its boundary the scoop shovel is caused by diagonal cuts to widen the working place to the required width. As the work is retreat ing, no pillar or only a foot or so has to be left, this being to pre vent fallen roof rock in the ad vance room from being loaded by the scraper in the adjacent room. The scoop shovel gathers the binder or partings with the coal and sometimes, when the bot tom is soft, scrapes up the bottom clay, especially if there are rolls. For this reason the scraper is used only in coal that is reason ably free of irregularities.Short inclined elevating con veyors have been designed for hand loading. The upper end of these inclined conveyors is high enough to load into a mine car. The lower end rests so near the floor as to make loading easy. This type of conveyor can be moved around either on a track or on the floor. In some instances it has a self-propelling truck and power-driven capstans for handling the mine car back of the loader.

A large number of conveyor loaders has been designed and used that pick up their own coal and pass it by a conveyor to another swiveling conveyor that discharges the coal into a car. The main difference between them is in the means by which the coal is lifted from the bottom. One well-known machine has gathering arms which pull the coal onto an inclined conveyor. Most types rely on the conveyor itself to do its own gathering.

The conveyor in one type has a chain, working on sprockets with vertical axes, which sweeps the coal onto and up an inclined trough. Others have vertical sprockets and the flights being buried in the loose coal lift it onto the conveyors. One such con veyor has loaded an average of 466 tons from room and entry faces in eight hours over a period of a month. Another shortwall ma chine combines cutting and loading. It cuts the coal, which is then shot down. The machine is sumped again into the loose coal and fed as for undercutting, but for this part of the service two other bars like the cutting bar but shorter are provided. They, with the cutter bar, drag out the coal and force it onto the flights of a conveyor.

Another quite recent machine is only 26 in. high. It has only one conveyor chain working on sprockets with vertical axes. This conveyor not only lifts the coal from the floor but places the coal in the mine car or a room conveyor, the conveyor itself being so arranged that one end can be swiveled. The intention, however, is not to bring the mine car to the loading machine but to have the loader dump into a portable shaking conveyor running on the room rails with the loading mechanism of this conveyor serving (I) as a flight conveyor to lift the coal from the conveyor to car height, (2) as a car feeder to spot a line of cars in front of the loading chute at the entry as desired and (3) as a locomotive to haul the conveyor from room to room.

Another type of loader is a power shovel that is forced under the coal and lifted. The shovel has no back and consequently the coal falls off the rear of the shovel onto a conveyor, by which it is conveyed to the swiveling conveyor which drops it into the mine car. This has been modified so that where the first conveyor can be loaded by the advance of the loader without a movement of the shovel the equipment can be used in this manner. Another type of shovel loader has an hydraulic pillar which bears against the roof and around which as a trunnion the whole equipment turns a full circle of 36o degrees if necessary. The shovel is forced under the coal pile and withdrawn. It is then lifted and swung over the mine car, whereupon it is emptied by an ejector plate.

For heading-driving, one machine is provided with an under cutting bar and two shearing cutters with a number of picks which break the coal down, which then falls and is removed by an in clined conveyor. Another machine has two revolving cutters that cut two interlapping tunnels in the coal with a chain that cuts the top and bottom. It makes an entry i i ft. wide and about 6 ft. high with flat roof and floor line but with sides which are segments of circles.

Stripping Methods.

Open-cut mining is the term applied to the working of mineral deposits which either outcrop at the sur face of the ground or are covered by a shallow overburden or cap ping, which must be removed before the ore can be mined. In coal mining work mining by this means is generally termed stripping. Since the cost of removing the overburden is charged to the cost of mining a point is reached, as the cover increases in thickness, beyond which open-cut mining does not pay and some method of underground mining must be used.One of the most distinctive features of open-cut methods in American coal mining, one that probably cannot be found in any other country or in any other type of mining in the United States or elsewhere is the method of stripping by casting. There are many strippings in the United States where the overburden is loaded by shovels or drag line excavators into cars, hauled to a distance and dumped. This is the most usual way of uncovering mineral in Europe and in America. Large machinery is sometimes used, as at Yallourn in Australia, where one 37o-ton shovel, one zoo-ton shovel and one i 50-ton shovel with respective bucket capacities of 9, and 2 cu.yd. are installed, and Hazleton, Pa., where a 6-cu.yd. shovel weighing 23o tons is being used. Here the maximum cover to be removed is 165 feet.

In Yallourn, conveyors are used instead of cars but the usual American method is entirely different. If the coal outcrops, the cover is lifted off the coal in a long swath i oo or more feet wide by a steam or electric shovel or drag line excavator and dumped down the hill. If the coal does not outcrop, the cover is similarly lifted from the coal and deposited along the property line. A smaller steam or electric shovel follows the stripper and lifts the coal into mine cars which carry it to the tipple. Where the coal occurs in a knob or small hill the two shovels chase each other round the hill, the stripper uncovering the coal and depositing the spoil where the coal has been removed by the coal shovel. In this manner none of the overburden is moved more than roo to 125 ft., and it is all done without the use of cars or conveyors. The cars are used solely for transporting coal. As much overburden as 10 or 12 times the thickness of the seam being worked has been removed. In rare instances as much cover as 7o ft. has been taken but the difficulty of finding space for the spoil and the dis advantages in making such big cuts limit the overburden taken even with thick coal. The Binkley Mining Co., at Seelyville, Ind., uses a Bucyrus-Erie shovel with a 3o-cu.yd. dipper on a io5-ft. boom and a 72-ft. dipper stick, with a dumping range of 113 f t. and a dumping height of 74 ft. for stripping coal. A still larger shovel, with a 32-cu.yd. dipper has been built by the Marion Steam Shovel Company.

Regulation and Inspection.

Owing to the many States in which mining is pursued and in part to the varied conditions in each State and to the differences in their accident records, the laws vary greatly and, as some think, unduly. The anthracite and bituminous mines in Pennsylvania have entirely separate laws. Each State has its own inspectors and some have both State and county inspection. The U.S. Bureau of Mines is almost solely a re search body. It had at one time regulatory power over properties in the segregated Indian lands and in the areas mined under lease from the U.S. Government. The authority has been transferred to a division of the General Land Office, Dept. of the Interior.The bureau has examined and approved several explosives and several types of mining equipment which it has declared "permissible," the word "permitted" not being used as in Britain, because the bureau has no power to admit or exclude explosives or equipment under the U.S. Constitution. The bureau has established mine rescue stations and equipped cars for the same purpose, and these are used most effectively for the saving of life in the larger mine disasters.

Safety.

Safety conditions in coal mines have been greatly im proved in recent years. The total fatalities in coal mines in the United States in 1938 numbered 1,128, of which 1,073 were underground, 11 in the shaft, and 44 on the surface. This com pares with a total of 2,176 fatalities in 1928, and 2,58o in 1918.(R. D. H.; X.)