Coast Erosion and Protection

COAST EROSION AND PROTECTION There is a difference of opinion about the value of much of the works for coast protection, and some consider that money expended thereon does not give an adequate return. Even in Holland, whose existence depends on the maintenance of its sea walls and defences, authorities are divided on important questions both of principle and practice. Since the close of the i9th century there has been remarkably little development in the means adopted to combat coast erosion; and, generally speaking, the methods of construction which still find favour, not only in Great Britain but also abroad, are the same in principle as those which have been used for generations pre viously. The royal commission on coast erosion, appointed in 1906, whose final report was issued in 1911, collected and placed on record much useful information on the subject of coast erosion, protection and reclamation, not only relating to the United King dom but also in reference to foreign countries and Holland and Belgium in particular.

The recommendations of the commission regarding the control of the foreshores of the United Kingdom and the constitution of a central sea defence authority have not yet been given effect to by legislative enactment. The report, however, has served to dispel certain erroneous ideas, particularly as to the extent of the loss of land due to erosion in the United Kingdom, and proves conclusively that the expense of protecting purely agri cultural land is out of all proportion to the value of the land thereby saved from destruction.

Causes of Sea Encroachment.—Encroachment of the sea on the coasts is due to erosion of cliffs and shore material. Of the detritus derived from such erosion a portion is carried along shore by the combined action of wind, waves and tides. It re mains in a state of more or less constant movement until it is fi nally deposited to swell an accreting sand or shingle bank, or is driven against some natural or artificial barrier, where it lies and is perhaps buried under subsequent deposits. The travelling shingle and sand or littoral drift is the principal source of the beach materials which form, and make good the wastage from, the foreshores of the coast. But in the course of this lateral travel the particles, large and small, forming the detritus are still further disintegrated. The lighter material is carried off in suspension by the sea and ultimately finds a resting-place on the ocean bed at a level below the influence of wave action or tidal scour.

The remaining portion of the solid materials derived from the destruction of the cliff or shore is more or less immediately trans ported into deep water, the finer particles being rapidly swept away by the current until finally deposited on the sea bed, and a certain proportion of the larger material, too heavy to be carried in suspension for any considerable distance, is drawn down the foreshore and the bed of the sea by the under-tow of the waves and ultimately makes its way by gravitation into deep water where it finds a resting place.

Deep Sea Erosion.

The process of erosion and littoral drift is not confined to the foreshore and beach above low-water mark.

Such changes are continuously in progress below low-water where wave action or tidal scour is capable of affecting the sea bottom. These agencies and the gravitating tendency of the particles continue at work until the opposing forces reach a condition of equilibrium. Under certain conditions material lying on the sea bed below low water and in shallow depths is driven back on to the foreshore, but this is merely a temporary phase in the progress of littoral drift. With change of wind or tide the conditions may be reversed.

Conditions Affecting Littoral Drif.

The direction of the prevailing littoral drift is in general governed by the direction of the flood-tide, the prevailing winds and the shape of the coast. Opinions differ as to the relative effect of tide and wind, and al though the direction of drift is at times varied by the wind direc tion, and the consequent wind waves, most competent authorities agree that, in the case of Britain at any rate, the prevailing drift coincides with the set of the flood-tide. In fact, on the British coasts the direction of the flood-tide does generally coincide with the direction of the prevailing winds. On the east coast the drift is from north to south and on the south coast from west to east, in both cases in the direction of the flood-tide and prevailing wind.Where a coast-line is broken up by deep bays and indentations no continuous drift can take place, each bay retaining its own characteristic material which is prevented from leaving it by the projecting headlands extending to low water or beyond and forming natural groynes. Numerous examples of these conditions are found on the south coast of Devon and Dorset. The direc tion of the flood-tide is also in many cases altered locally by the configuration of a bay; e.g., the deflection of the tide along the shores of the bay in a direction opposite to that of the normal coastal current. In cases where a coast-line is broken up by estuaries or rivers the results are variable, depending upon the continual struggle which takes place between the opposing forces affecting littoral drift and the tidal inflow and outflow of the river, the latter sometimes aided to a material extent by the addition of large volumes of fresh water.

During strong winds in a direction contrary to the set of the tide the normal travel of drift may be nullified or even reversed. The accumulation of material on a foreshore is gener ally brought about by tidal and wave action in calm weather, and a beach which has been depleted during a long spell of heavy weather usually makes up again, at any rate to a partial extent, on the occurrence of calm sea and the cessation of wind. This re plenishing is due to the return of a portion of the material previously drawn down into shallow water below low-water mark. Generally speaking, on-shore gales result in the drawing down of the beach material and its gravitation towards the deep sea. Off-shore winds, on the other hand, frequently lead to the accumulation of material on a foreshore.

In order to increase the extent of a foreshore or to maintain it even in its existing condition, the natural and incessant losses must be made good by accretion or the trapping of material derived from other parts of the coast. This may be done in favourable circumstances by the construction of groynes or other works similar in effect, but the accretion through their agency is in every case accomplished to the detriment of neighbouring foreshores. Thus the large groynes at Brighton trap for the time being the greater part of the shingle travelling from west to east, and very little passes on to the foreshore to the east of Brighton, which has consequently become denuded.

Effect of Artificial Projections on Adjoining Coast.— The construction of solid piers or other similar obstructions at an angle with the general shore line and projecting into the sea is, when occurring on a coast-line subjected to erosion, almost inevitably followed by serious depletion of the foreshore to leeward. The solid projection, which in many cases is carried sufficiently far in a seaward direction to reach comparatively deep water, effectively hinders the passage of littoral drift from its windward to its leeward side. (The terms "windward" and "leeward" are used in the sense understood by engineers en gaged in coast protection work; viz., "windward"—the direction whence the prevailing littoral drift proceeds ; and "leeward"— the direction towards which such drift takes place.) Thus the erosion of the lee shore is accelerated by the loss of the travel ling material which under natural conditions makes good to a partial extent the ravages of the sea. Instances of such stop page are numerous on the English coast. The Folkestone har bour pier has arrested the travel of the beach from the west ward, and led to the accumulation of a large bank on that side and the denudation of the foreshore to the east of the harbour and towards Dover. The construction of the harbour works at Dover has stopped the eastward drift at that point and ac celerated the destruction of the cliffs in St. Margaret's Bay. At Lowestoft the construction and subsequent extensions of the harbour pier and other works which project at right angles to the coast-line at the sea outlet of Oulton Broad have resulted in the accumulation of a bank of shingle to the northward and serious encroachments on the town frontage to the south of the harbour.

Sea Walls.—The conditions affecting the design of a sea wall differ so materially that every case must be considered on its merits and provided for accordingly. Sea walls may be divided roughly into two classes, sloping and upright, each class having its advocates among engineers. Generally speaking, walls having a sloping face are used in Holland and Belgium, whilst a vertical or nearly vertical face is more common in Great Britain. The immediate effect of the construction of a wall is detrimental to the beach in front of it, although affording protection to the cliff or banks behind. Thus the construction of a sea wall on a sand or shingle foreshore is in itself calculated to bring about the denudation of the beach and the wall may become before long the agent of its own destruction. Whilst the wall will prevent erosion by the sea of the cliffs in rear of it, the beach in front of the wall must be protected and conserved by the construction of groynes. Many walls have failed through the displacement of the filling behind them by wave action; the provision of a substantial and wave resisting surface or paving behind the wall is, therefore, of great importance, and has been too often neglected. Suitable provision for the drainage of the cliffs, where they exist at the back of sea walls, is also a matter of high importance which also has often been neglected with disastrous results. Much can undoubtedly be done by draining, sloping and planting, to preserve and protect cliff faces, and these works ought to proceed simultaneously with the carrying out of sea-defence undertakings, when the cost of the latter is justified, to protect the foot of the cliff.

Sea walls subjected to abrasion by shingle are, if faced with concrete, very liable to progressive and serious damage. In such positions a concrete wall is frequently protected by a facing, at any rate over that portion subjected to abrasion, of hard stone or flints. For this reason also reinforced concrete is unsuitable for use in the face work of walls on a shingle beach, as the wearing away of the concrete soon results in exposure and deterioration of the steel reinforcement.

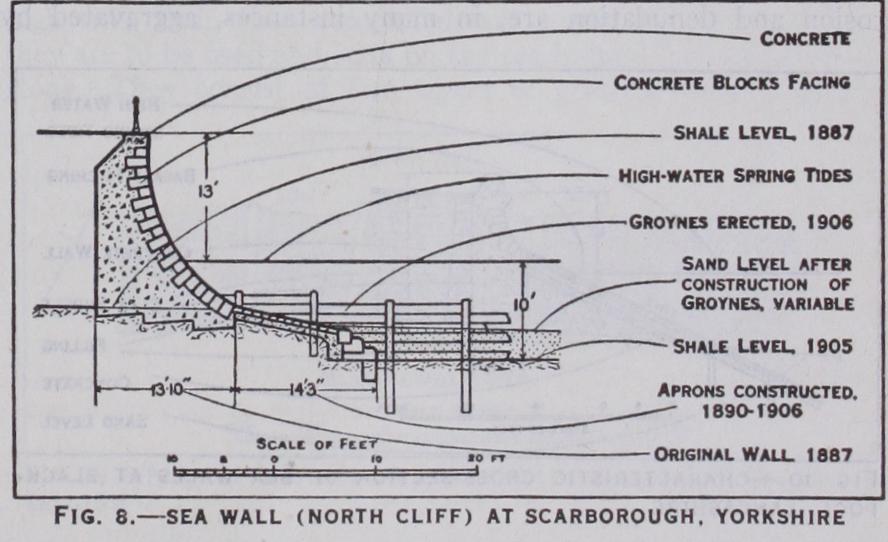

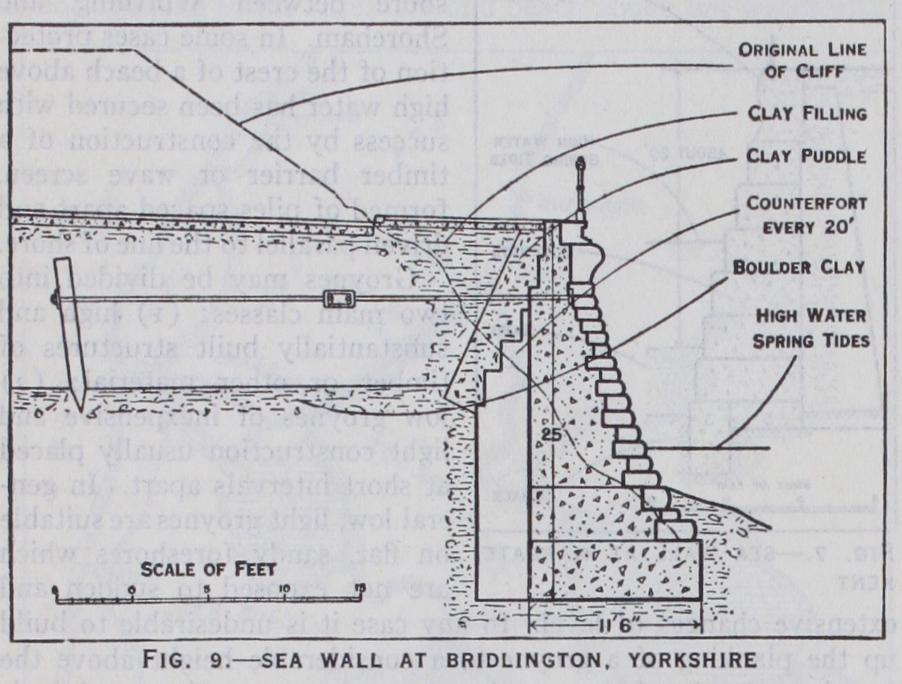

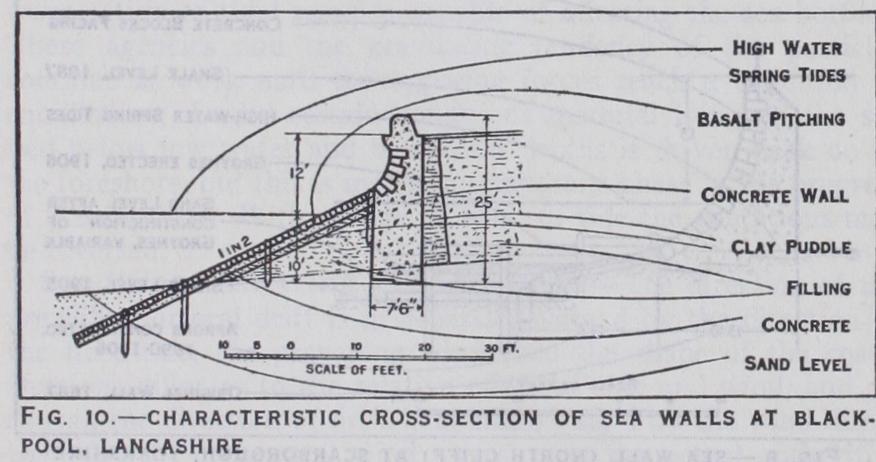

Upright sea walls, with some batter on the face, have been constructed along the frontage of many sea-side towns, with the double purpose of making a promenade or road, and of af fording protection. A very slop ing and also a curved batter reduces the effective stroke of the wave by facilitating its ris ing up the face of the wall, but the force of the recoil is correspondingly augmented. A vertical face offers more direct opposition to the wave, min imizes the tendency to rise and, consequently, the recoil ; while a stepped face tends to break up the wave both on ascending and recoil, but there is a corresponding liability to displacement of the face blocks of the wall. The sea walls shown in figs. 6, 7 and 8 exhibit straight, stepped and curved forms of batter. The building of the Scarborough wall (1887) was followed by erosion of the shale bed on which it was founded, and further protective works, including aprons and groynes, had to be added subsequently. A sea wall at Bridlington, constructed in 1888, and, like the walls at Hove and Scarborough, protected by groynes, is shown in fig. 9. At Blackpool walls of the Dutch type but with somewhat steeper aprons have been built on an extensive front (fig. i o) .

Groynes.—However effective they may be in collecting travel ling material, groynes will not in all cases prevent the waves reaching the top of a cliff or bank and eroding it to a greater or less extent. A combination of the two forms of protection- groynes and wall—is frequently desirable, but groynes alone have on many low-lying foreshores, particularly where there are no cliffs, proved successful and efficient without the construction of sea walls or protected banks, as for instance on the four m. of shore between Worthing and Shoreham. In some cases protec tion of the crest of a beach above high water has been secured with success by the construction of a timber barrier or wave screen, formed of piles spaced apart and driven parallel to the line of shore.

Groynes may be divided into two main classes : (I ) .high and substantially built structures of timber or other material; (2) low groynes of inexpensive and light construction usually placed at short intervals apart. In gen eral low, light groynes are suitable on flat, sandy foreshores which are not exposed to sudden and extensive changes of level. In any case it is undesirable to build up the planking of a groyne to a considerable height above the foreshore level existing at the time of construction, and it is preferable to raise the groyne by the addition of planking to keep pace with the accretion of beach material. The use of reinforced concrete for the construction of groynes has frequently been advocated, but is unsuitable on shingle beaches on account of the rapid abrasion of the thin concrete covering of the steel reinforcement.

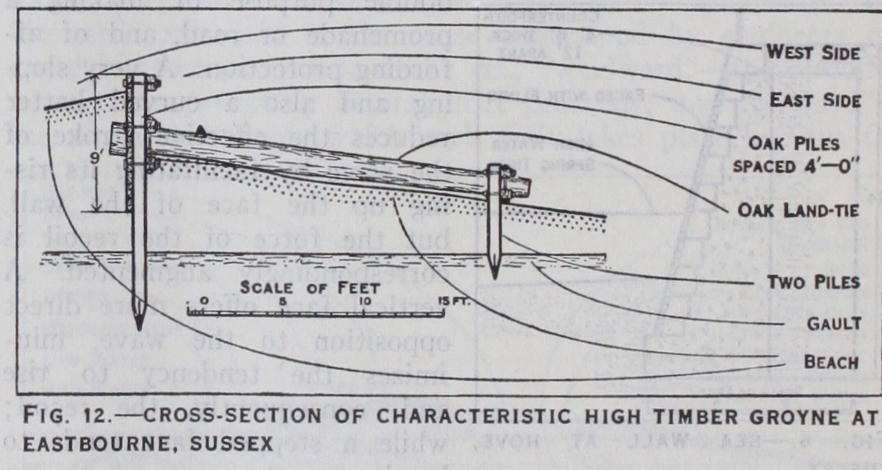

Groynes although, in Britain, usually constructed of timber are sometimes built of concrete or masonry; examples are the high groynes at Brighton and Hastings (fig. II), which are faced with flints to protect the concrete from abrasion by shingle. A typical high timber groyne at Eastbourne is shown in fig. 1 a and a low groyne of lighter construction in fig. 13.

Groynes, speaking generally, to be of maximum efficiency should be at distances apart about equal to, or little more than, their length. They should extend continuously from the shore or work to be protected to the vicinity of low water of spring tides. There is much diversity of opinion and practice with regard to the direction in which groynes should point. Some authorities advocate their direction at right angles to the shore line, others pointing slightly to windward and some prefer a leeward direc tion. No general rule can be laid down and a plan suitable for one locality may prove a failure in another. The opinion of the majority of authorities, however, appears to favour a direction pointing slightly to windward.

Relative Extent of Loss and Gain of Land.

The evidence as regards the total superficial area gained and lost in recent years on the coasts and in the tidal rivers of Great Britain shows that far larger areas have been gained by accretion and artificial reclamation, taken together, than have been lost by erosion. Evidence laid before the royal commission by the Ordnance Survey Department in 1907 showed that within a period, on the average, of about 35 years, about 6,64oac. had been lost to the United Kingdom, while 48,000ac. had been gained. Most of the gain has been in tidal estuaries, while the loss has been chiefly on the open coast. Moreover, the gain has been due in the main to the deposition of sediment brought down by rivers and to artificial reclamation. It is, however, probable that the land lost has been more than compensated for by land naturally accreted. The report of the royal commission contains the following statement : "The erosion . . . would have been far more serious if ex tensive works of defence had not been constructed by local authorities, railway companies and others, at a great cost, though, on the other hand, such works in many places have been re sponsible for erosion of the neighbouring coasts by interfering with the normal travel of the beach material. On the whole we think, however, that while some localities have suffered seriously from the encroachment of the sea, from a national point of view the extent of erosion need not be considered alarming." Removal of Shingle.—Beach material is too often limited in quantity and the question arises whether its removal for commercial purposes should be allowed. The results of natural erosion and denudation are, in many instances, aggravated by this practice. The powers possessed by the Board of Trade provide for the issue of prohibitory orders and, in certain cir cumstances, where the removal of beach or sand can be shown to be injurious, such orders have been frequently made.

Cost of Coast Protection.—The cost of construction of groynes varies very considerably with the design and local con ditions. Before the World War light low groynes might be con structed at a cost of from los. to Li per foot lineal, and groynes of more substantial construction from Li to L3 per lineal foot, while some of the large concrete and masonry groynes, of the type frequently constructed at Brighton and Hastings, cost as much as £7 or £8 per lineal foot. The initial capital cost of pro tection per mile of shore was seldom less than £4,000, even when no sea wall was constructed. Under present conditions these figures should be nearly doubled. The annual charge for repairs, interest on capital, and replace ment may be put at not less than i o% of the original capital cost.

The cost of protecting purely agricultural land which is subject to erosion must of necessity, un der the conditions which usually prevail, be considerably in excess of the value of such land.

Protection under such conditions is only justified when agricul tural land is in the vicinity of towns, and erosion, if not stopped, is likely to lead to those towns being outflanked by the sea and in situations where the works have as their object the preserva tion from inundation of areas of low-lying land of considerable extent. It is not desirable, even if it were practicable, to prevent erosion of all parts of the coast, as the waste of the cliffs provides the greater part of the beach material which acts as the most valu able agent of protection.

The expenditure incurred in the construction of sea defences by many of the coastal towns of Britain in recent years has been very considerable and in some cases has imposed a heavy burden on the inhabitants. As an instance the case of Sidmouth, a seaside town on the south coast of Devon, having a population of about 6,000, may be referred to. As a result of exceptional gales the sea defences of the town over a frontage of under half a mile were seriously damaged and undermined between the years 1917 and 1925 and the construction of new sea walls and groynes, completed in 1926, entailed an expenditure of over £ i oo,000.

Sand Dunes and Alluvial Flats.

The preservation of sand dunes is most important along certain parts of the coast where they afford protection to low-lying areas behind them, and they should in these cases be maintained and fostered by the encourage ment of the growth upon them of marrum and other grasses, which help to bind the sand together. Where drifting of blown sand occurs much may be done to check it by the fostering of such grasses. The process of natural accretion on alluvial flats has been hastened in many cases by the planting of suitable vegetation such as rice grass (spartina), and in this way land may in time be reclaimed by entirely natural means.