Coco-Nut Oil and Cake

COCO-NUT OIL AND CAKE. The bulk of the world's supply of copra and coco-nut oil (the older spelling cocoanut is obsolete) is derived from the fruit of the variety Cocos nuci f era of the coco-nut palm, which grows on the coast of all tropical countries, and is extensively cultivated in the Malay Archipelago, India and Ceylon. When fully ripe the nuts contain only a small amount of milk, the bulk having coagulated to form the thick, fleshy endosperm—coco-nut "meat." This "meat" contains about 3o to 40% of oil and 50% of water. The nuts are collected, and each split into three parts (by native labour) with an axe or by striking on an iron spike fixed in the ground. The coir is removed and the broken kernels dried. The resulting dried meats, which shrink away, and are readily detached, from the shells, are termed copra ("copperah"). One thousand nuts yield from 44o to 5501b. copra containing approximately of water. It is found necessary to dry the meats as the large amount of water present in the fresh kernels favours the growth of fungi, leading to rapid putrefaction of the albumenoids present in the endosperm and consequent rancidity of the oil.

Drying Copra.

The earliest method of drying was to expose the kernels to the air and sun, a practice still extensively followed which gives a good quality white copra ("sun-dried" copra). A more rapid primitive process, adopted particularly in districts where the humidity of the air is excessive, is drying by fire ("kiln drying"). The older method was to spread the kernels on a grating of bamboo cane over a slow fire. As this practice exposed the kernels to the smoke from the fire, an inferior quality copra resulted. Further, in these primitive kilns the copra was fre quently charred on the outside, causing it to yield a yellowish oil almost impossible to bleach. A more satisfactory method, first introduced in India and Samoa, is to dry by means of hot air. The meats are spread over a lattice of bamboo sticks covered with coco-nut leaves, placed on trays, and drawn slowly through a heated tunnel meeting a counter-current of hot air. This method yields the finest and whitest copra, which fetches a higher price than the sun-dried article, and is sold chiefly for the "desiccated coco-nut" used in confectionery. It is stated that even better results are obtained by the use of rotary driers, recently intro duced in the West Indies. The fresh kernel yields about 6o% of dried copra. To inhibit the growth of fungi the amount of water in the dry product should not exceed 4%, although a large amount of the copra on the market contains as much as io%. The pro portion of oil in kiln-dried copra varies from 63 to 65%, while in the hot-air dried product it may rise to 74%. The bulk of the copra is used for the subsequent production of coco-nut oil and cake.

The oil of the coco-nut has been used as an article of food from ancient times. The earliest method of obtaining it was to break the raw kernels into small pieces and expose them to the sun in heaps, from which the oil ran out spontaneously. An improved method, practised in India from a very early date, consists in triturating the sun-dried copra in a mortar and then subjecting the mass to pressure in simple primitive presses. By the native method which produces the finest and whitest oil, the fresh ker nels are pounded to a pulp and thrown into boiling water. The clear oil as it rises to the surface is skimmed off, the residual pulp, "coco-nut poonac" is used as a cattle food. This process, carried out on a large scale at Cochin on the Malabar coast, has survived to the present day, "Cochin" oil still representing the highest quality. This is in part due to the short time the oil remains in contact with putrescible matter. When prepared with the same care, oils equalling the finest Cochin oil can be, and are, produced in other places (e.g., Ceylon).

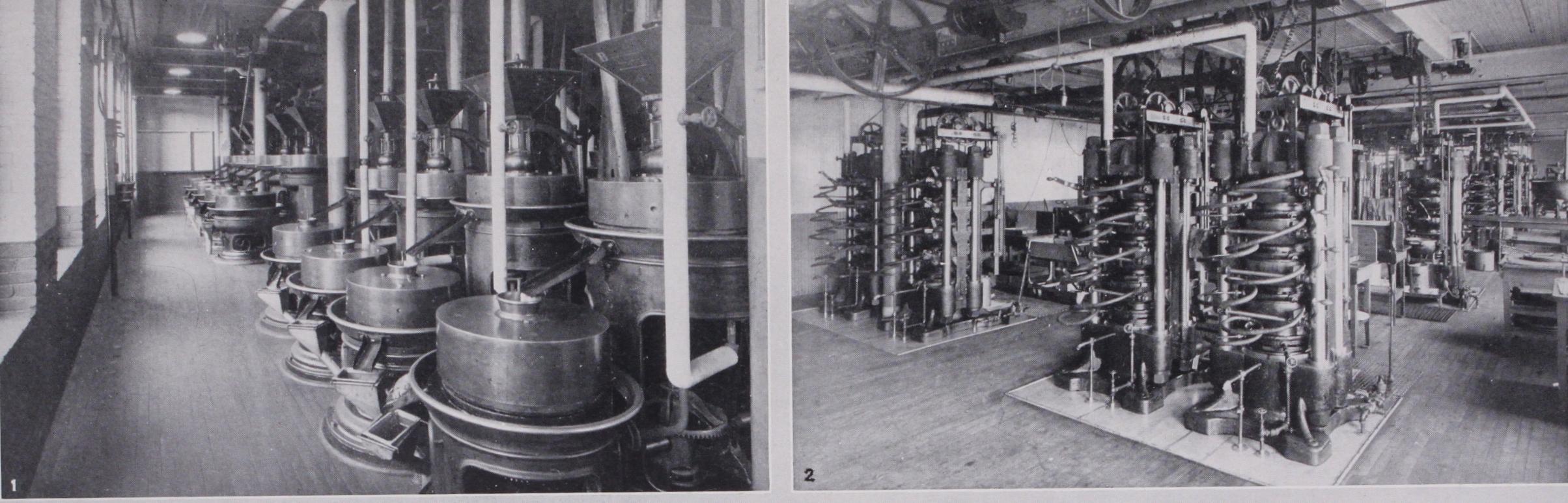

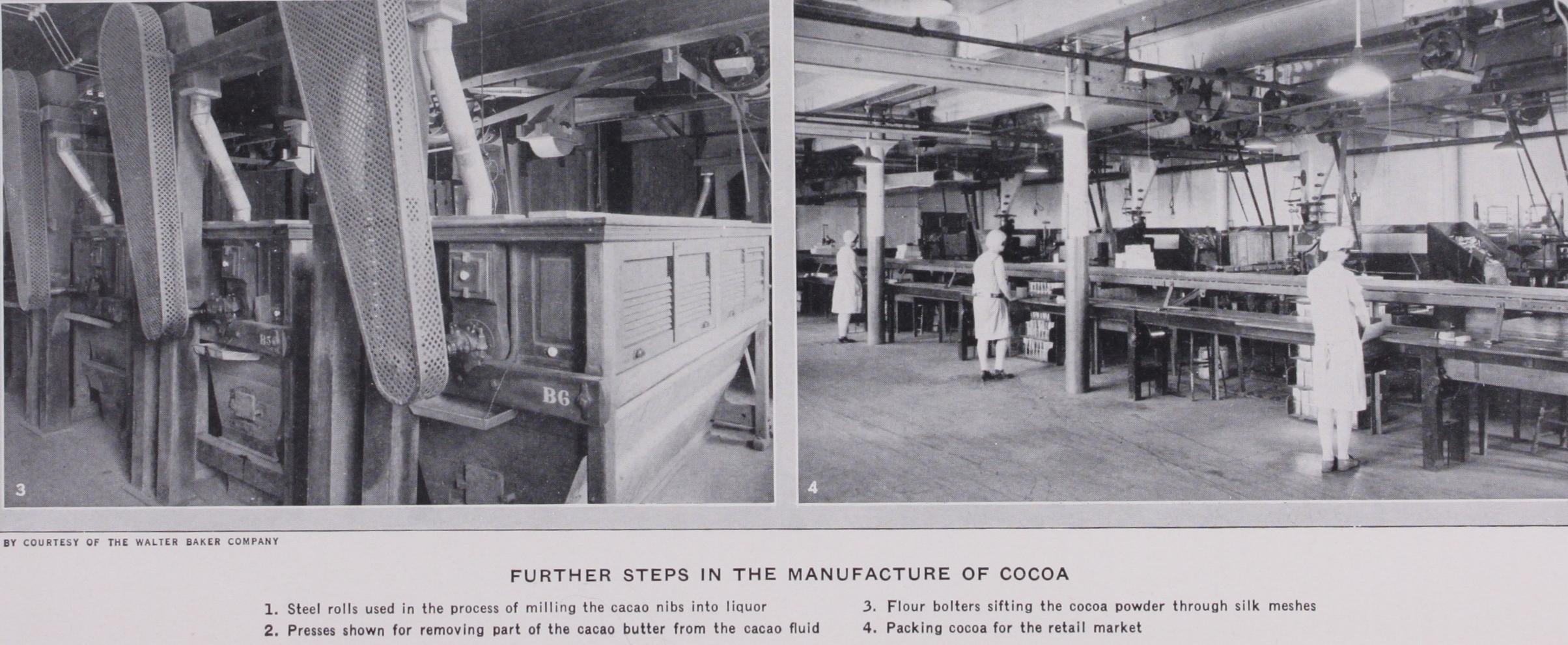

Hydraulic Pressing.

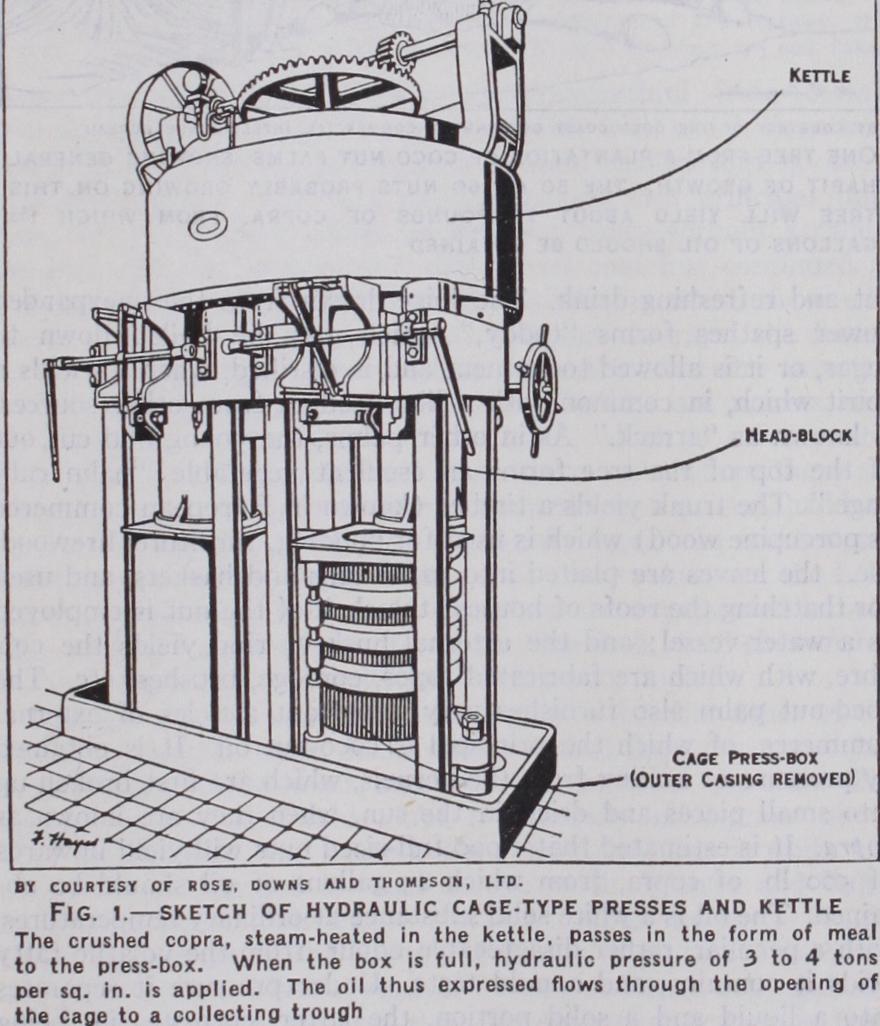

The coco-nut oil extracted in Europe from imported copra is prepared by comminuting and express ing the mass in hydraulic presses. In India and Ceylon large central hydraulic installations are gradually superseding the primi tive native presses.

Preparatory to pressing, the copra is passed over a magnetic separator to remove any pieces of iron (hammer-heads, nails, etc.) and reduced to a meal by passing between fluted revolving chilled-iron crushing rolls. From these it is carried by means of an elevator into the "kettle" which is placed above the presses. In this it is heated to a temperature of about 6o°C. and moistened by steam. This treatment ruptures the cell-walls, thus enabling the oil to exude more readily. The kettle delivers the material in quantities sufficient to form one cake at each operation. These cakes ("cooked meats") are then delivered to the presses, which may be "cage" presses or of the "Anglo-American" type. Copra is so rich in oil that it requires at least two pressings.

The "cage," or "clodding," press consists of a circular box built up of steel staves held in position by steel hoops ; the staves almost touch one another, but the oil can flow through the inter stices while the meal is retained. The "cooked meats" are sepa rated by flat mats of wool or hair and are compressed by the rising hydraulic ram. As the mats have to bear very little strain, there is a large saving in wear of press cloths in the cage press as pared with the Anglo-American press. This machine, also known as a "plate press," consists of a number of rectangular plates, between which the meal-cakes (wrapped in cloths or bags) are placed, and which are forced gether by the action of the ram. This type of press yields more coherent cakes and is used for the final pressing, but the cage press is to be preferred for the first pressing of a material so rich in oil as copra, since there is less tendency for spueing of the meal.

The Cake.

The pressure on the meal in the cage press is gradually increased to a maxi mum of three to four tons to the square inch. When the oil has ceased to flow the cakes are re moved and broken up in a special machine termed a "cake breaker." They are then re cooked and subjected to similar pressure in the plate press. On removal from this press the edges of the cake, which are richer in oil than the bulk, are trimmed,off. The cakes ("coco-nut oil cake") thus formed are sold as a cattle food to the stock-raiser. They contain from 7 to of oil, and although poorer in proteins than linseed cake, are valued by the farmer for dairy cattle, as they are supposed to stimulate milk production ; this assumption has not been fully confirmed. The parings of the cakes are re-pressed to obtain more oil. Mouldy or rancid cakes from low-grade copras unfit for cattle food are ex tracted with a volatile solvent to recover the oil they contain.Coco-nut oil, which is liquid in the tropics, is a solid fat in temperate climates, white to yellowish in colour and possessing a characteristic odour of coconut flesh. It is distinguished chem ically by its low iodine value (absence of unsaturated fatty acids) and by the presence of considerable quantities of glycerides of the lower saturated fatty acids (myristic and lauric) and also of the volatile capric, and caprylic acids. As it possesses the exceptional property of being saponified by simple mixing with warm con centrated caustic lyes, it forms the principal ingredient of cold process soaps. It is valued in milled and "washer" soaps (hard soaps made by the boiling process) owing to the free-lathering properties it imparts to them. As coco-nut-oil soap is soluble in brine, it is used in "marine soaps" intended for use at sea. Coco nut oil is also largely employed in the manufacture of margarine, vegetable butters, lards, etc., and as a substitute for cacao butter in the manufacture of chocolate. For edible purposes the free fatty acids must be removed by means of alkali and the oil deodor ized by treatment with superheated steam in vacuo. It can be stiffened by expressing some of the more liquid constituents.

Coco-nut oil has also been suggested as a fuel for Diesel engines, and its use for hatching jute has been patented.

The following figures show the distribution of exports and im ports of copra and oil of the principal producing and consuming countries. (Figures from the Year Book of Agricultural Statis tics 1926-27, International Institute of Agriculture.) Coromandel coasts of India the trees grow in vast numbers; and in Ceylon, which is peculiarly well suited for their cultivation, it is estimated that 20 millions of the trees flourish.

The uses to which the various parts of the coco-nut palm are applied in the regions of their growth are almost endless. The nuts supply no inconsiderable proportion of the food of the natives, and the milky juice enclosed within them forms a pleas