Codes and Ciphers

CODES AND CIPHERS, general terms designating the methods employed in the practice of cryptography, or secret writing; often also used to designate the cryptograms pro duced thereby. In recent years, because of the growth of govern ments, the expansion of commerce, and especially the remarkable progress made in the art of electrical communications, they have become essential adjuncts to the conduct of diplomatic, naval, military and commercial affairs.

The final text of cryptograms to be transmitted electrically should, for reasons of practicability, be composed exclusively of letters of the alphabet, and, for reasons of economy, be arranged in regular groups of five or ten letters; cryptograms composed of groups of figures, although acceptable, are more costly and there fore not so common; those composed of intermixtures of letters and figures are rarely encountered, and those containing characters other than letters or figures are not accepted for transmission. Although in theory no sharp line of demarcation can be drawn between code systems and cipher systems, in modern practice the technical differences between them are sufficiently marked to warrant their being treated as separate categories of methods. It is convenient to consider cipher systems first, then code systems, with the understanding that only a very few of the limited number of systems suitable for serious usage can here be outlined.

Cipher Systems.—In general, cipher systems involve a crypto graphic treatment of textual units of constant length, usually single letters, sometimes pairs, rarely sets of three letters, these being treated as symbols without reference to their identities as component parts of words, phrases and sentences. Every practical cipher system must combine (I) a basic method of treatment which is constant in character, with (2) a keying principle which is variable in character and employs specific secret keywords, phrases, or numbers, the individual compositions of which deter mine or control the exact results under the basic method. The basic method must be such that even if known to the "enemy" no messages can be read by him unless he also knows the specific keys applicable to those particular messages.

Despite a great diversity in the external appearance and internal constitution of ciphers, there are only two basic classes of systems, transposition and substitution. The former involves a rearrange ment or change in the sequence of the plain-text letters, without any change in their identity ; the latter, a replacement of the plain-text letters by other letters or by figures, without any change in their original sequence. The two systems may be combined in a single cryptogram.

Transposition systems usually involve the inscribing of plain text letters in a more or less regular geometrical design, beginning at a prearranged initial point and following a prescribed route, and then transcribing the letters from the design, beginning at another prearranged initial point and following another prescribed route. The design may take the form of a rectangle, trapezoid, octagon, triangle, etc., but systems in which the specific keys con sist solely in keeping the designs, the initial points, and the routes secret are not often employed because of their limited variability. In this same class also fall systems which employ perforated card board designs called grilles, descriptions of which will be found in works listed in the bibliography. The system most commonly used in practice is that designated as columnar transposition, wherein the transposition design takes the form of a simple rectangular figure, the dimensions of which are determined in each instance jointly by the length of the individual message and the length of the specific key. An example is shown in fig. 1.

manner in which they are used in the enciphering process. As to their nature, cipher alphabets are of various types, and are known under various names, such as standard, direct, reversed, systematically-mixed, keyword-mixed, random-mixed, reciprocal, conjugate, etc., all having reference to the nature of the sequences of letters composing them, their manner of production, the inter relations existing among them internally or externally, etc. The most important factor in connection with a cipher alphabet is whether the sequence, regardless of its nature, is known or un known to the enemy ; for if its sequence is known, any conven tional or disarranged alphabet may be handled with the same facility as the normal or ordinary alphabet. As to the number of alphabets involved, substitution systems are either monoalpha betic, involving a single alphabet, or polyalphabetic, involving two or more alphabets. In essence the difference between them lies in the fact that in the former the equivalence between plain-text and cipher letters is of a constant or invariable nature throughout the cryptogram, whereas in the latter it is of a changing or variable nature. So far as secrecy is concerned, the third condition men tioned above, the manner in which the various cipher alphabets are employed, is the most important.

Monoalphabetic systems, an example of which is shown in fig. 3, can be passed over in a few words. They represent the simplest In the foregoing case the letters undergo a single transposition; in cases involving double transposition, that is, wherein the letters undergo two successive transpositions, the security of the crypto grams is very greatly increased, provided the methods selected are such as will effectively disarrange individual letters and not merely whole columns or rows. A practical system of double transposition is illustrated in fig. 2.

The principal advantages of transposition systems lie in their comparative simplicity, speed of operation, and, in the case of true double transposition, their high degree of security; but despite these important considerations they do not at the present time play a prominent role in practical cryptography because of certain defects inherent in and common to all methods of transposition.

Substitution systems involve the use of conventional alphabets called substitution alphabets or cipher alphabets, and the com plexity of any particular system depends upon three conditions: (I) the nature of the cipher alphabets employed, (2) the number of them involved in a single cryptogram, and (3) the specific types of substitution and, regardless of the type of cipher alpha bet employed, practically every example can be readily solved by the well-known principles of frequency.

The foregoing example illustrates monoalphabetic substitution which is monoliteral in character, that is, each letter is replaced by another single letter; biliteral monoalphabetic substitution, where each letter is replaced by a pair of letters, is sometimes encountered, and is illustrated in fig. 4.

Polyalphabetic systems are often referred to as double-key systems, and, as noted above, employ two or more cipher alphabets in the encipherment of single dispatches. In a given system the alphabets may be entirely independent of and bear no relation to one another, or they may be interrelated. In the former case their number may be unlimited, the separate alphabets being drawn up at random and arranged in any convenient manner; in the latter case the alphabets are limited in number and are inter related because they are secondary alphabets derived by juxta posing two basic or primary alphabets. at the 26 possible points of coincidence and noting the 26 different values given for plain text A, B, C . . . Z, for the 26 successive juxtapositions. In the sim plest case of interrelated alphabets, that resulting when the two primary alphabets are both normal sequences, proceeding in the same direction, the secondary alphabets are called standard alpha bets, which when successively tabulated yield a symmetrical table (fig. 5) known in the literature under various names such as Vigenere table, square table, quadricular table, etc. Such a table may be used in several ways. The most common method employs the top line as the plain-text alphabet and the successive horizontal lines as the cipher alphabets, each of which may be designated by its initial letter. Thus, the fourth or D alphabet is the one in which plain-text A is represented by cipher D, plain-text B, by cipher E, etc. In the ninth or I alphabet, A=I, B= J, etc. There fore, when several alphabets are to be employed in a message, the letters of a prearranged keyword can serve to indicate the number, identity, and sequence of the alphabets to be selected.

Various modifications of the simple Vigenere table are en countered, these involving different types and arrangements of alphabetic sequences in the table, but in every case where these sequences can be arranged so as to exhibit symmetry of position as regards the order in which the letters fall in the successive rows or columns, sliding or concentric primary alphabets may be em ployed to produce the same results as the table, and are often more convenient than the latter.

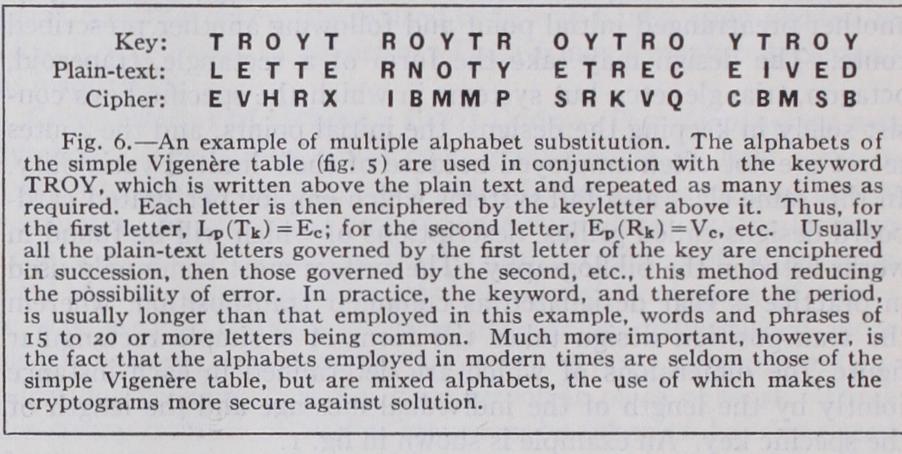

Polyalphabetic substitution systems may be classified as peri odic or aperiodic, depending upon whether or not the crypto grams produced by them exhibit external phenomena of a cyclic nature. Periodicity is exhibited externally whenever the substi tution process involves the use of repeating keying elements which operate in conjunction with a constant number of cipher alphabets. Periodic systems may be further classified into multiple alphabet and progressive alphabet systems. In the former type only limited numbers and specific members of the complete set of alphabets pertaining to the system are employed in a single message, the number, sequence and identities of the alphabets being governed in each case by the key, which is repeated as often as necessary to encipher the message. An example is shown in fig. 6.

In progressive systems all the cipher alphabets pertaining to the system are employed in succession in a single, definite se quence which may be repeated. Hence, the length of the period corresponds to the total number of cipher alphabets involved in the system. Usually the sequence in which the alphabets are used varies with each message, this constituting one of the impor tant factors in secrecy. To illustrate, suppose the system embodies a set of 5o mixed alphabets, each designated by a number. A numerical key consisting of the numbers from i to 5o, constructed either by random selection or by derivation from a word, phrase or sentence, is employed to control the sequence in which the alphabets are to be used in enciphering a specific message ; if the latter contains 500 letters, the sequence passes through r o cycles. Another message may be enciphered by a different numerical key; with 5o alphabets the total number of different numerical keys possible is . • XI, an extraordinarily great number.

Polyalphabetic systems of the aperiodic type present the great est diversity in construction. In these systems periodicity is either entirely lacking because of the inherent nature of the method, or it is suppressed by incorporating variable elements as period interrupters. In the aperiodic system designated as the running or nonrepeating key system, periodicity is avoided by employing for the key the continuous text of a book, identical copies of which are in possession of the correspondents. The starting point of the key is agreed upon in advance, or is signalled by special indicators to designate the exact point where the key begins. Another type of nonrepeating key system, often designated as the auto-key system, is that in which, beginning with a preconcerted keyletter, each cipher letter (or sometimes each plain-text letter) becomes the keyletter for the encipherment of the next plain-text letter.

Among the systems in which periodicity is suppressed by intro ducing a variable element, or interrupter, one of the simplest is that wherein encipherment is performed according to word lengths, each letter of the key serving to encipher a complete word by the same alphabet. Words being irregular in length, periodicity is suppressed. Another system, called the interrupted-key method, employs a keyword which is broken at irregular intervals by a subsidiary key, or by the insertion of a specially agreed upon letter serving as an indicator. Thus, using the keyword WEDNESDAY, a message may be enciphered according to the interrupted key WED/WEDNES/WE/WEDN/WEDNESD, etc. If a special in dicator is used, the interrupter may be inserted at will, since in decipherment its reappearance serves to indicate where the breaks in the keying sequence occur. Sometimes a prearranged plain text letter serves as the interrupter itself ; sometimes a cipher letter.

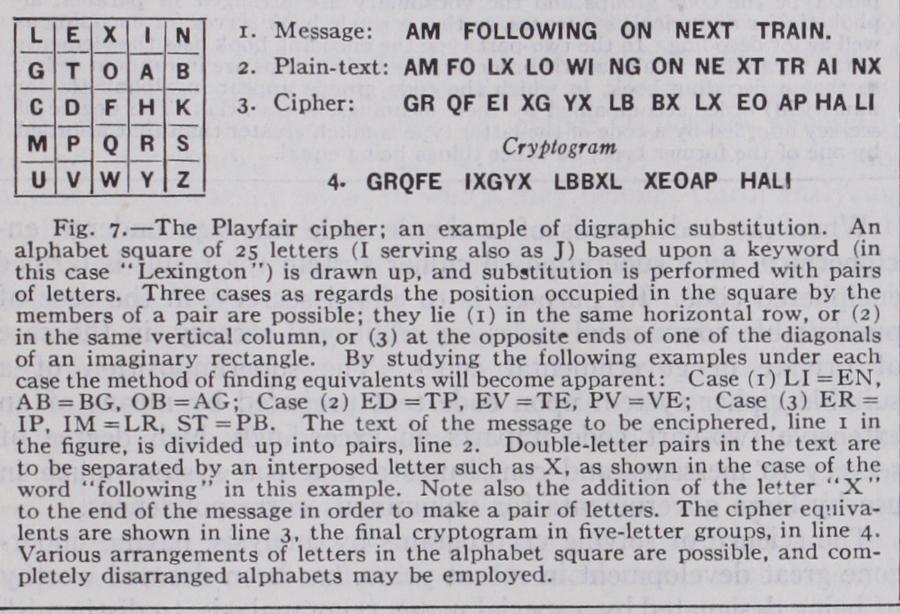

The various systems of substitution thus far mentioned are monographic in nature, involving single letters ; in digraphic sys tems, substitution takes place by pairs, usually by means of squares in which the letters of the alphabet are disposed according to agreement and the cipher equivalents of pairs are found by following certain rules. One of the best known methods is that called the Playfair method, illustrated in fig. 7.

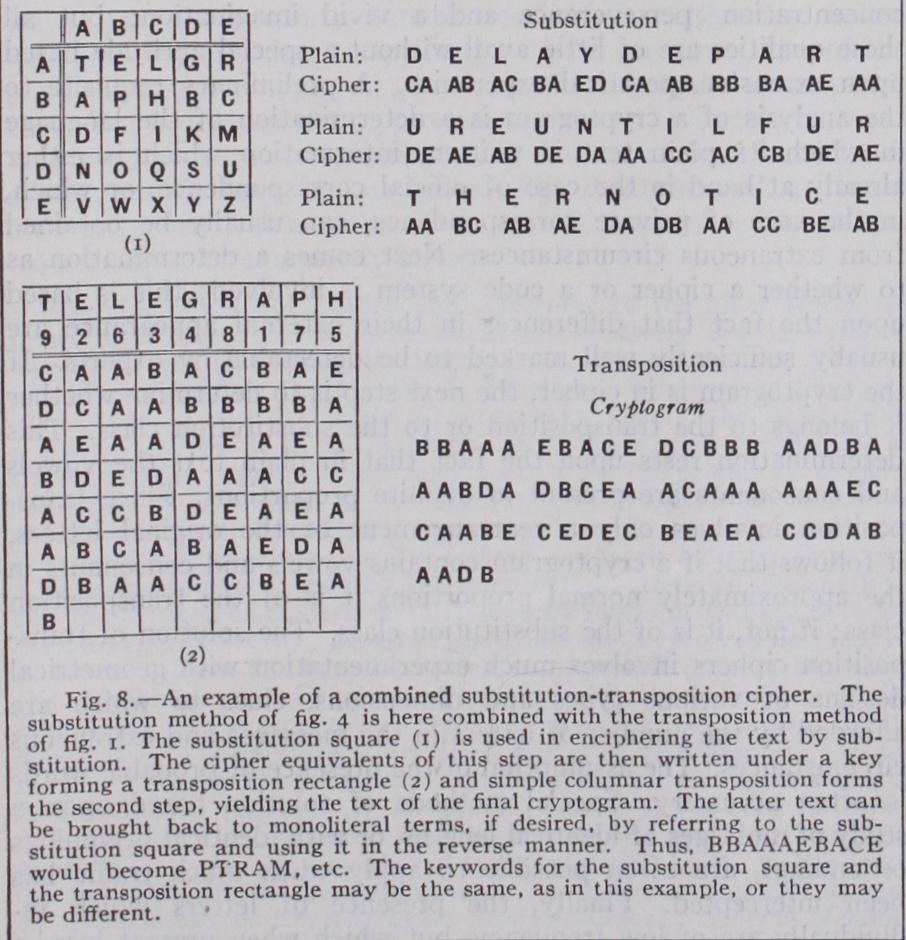

Properly selected methods of transposition and substitution when combined into a single system result in the production of cryptograms of great security, but because of the additional com plexities of operation introduced by the combination, with the resultant increased possibilities of error, such systems are not often encountered in practice. A good example, ingenious because of its simplicity and security, is that illustrated in fig. 8.

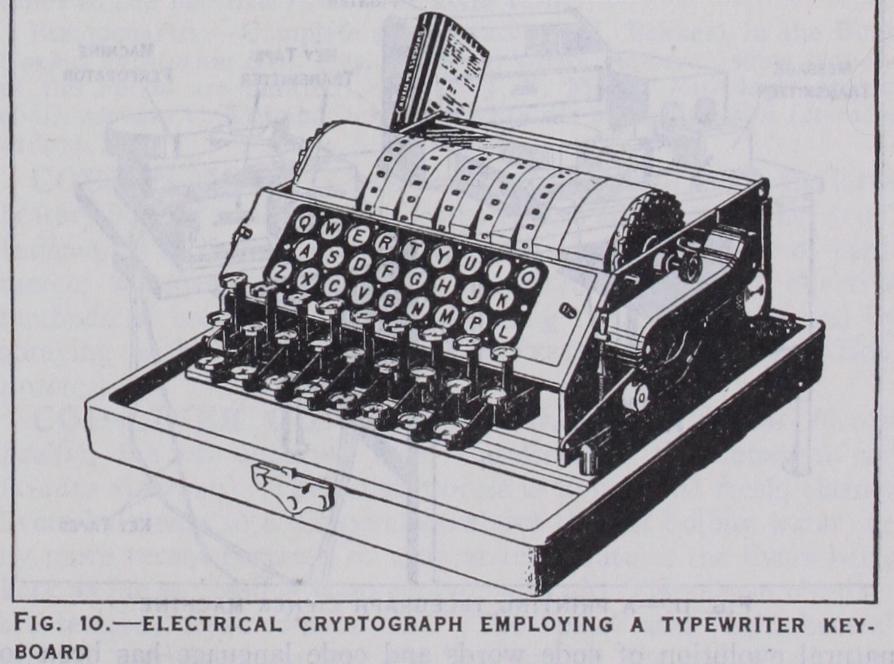

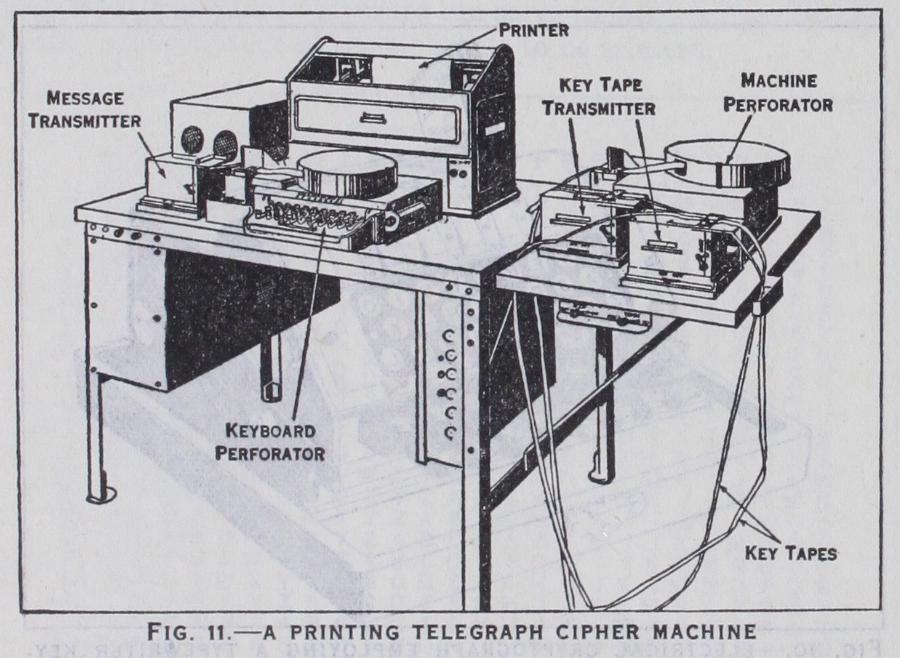

Cryptographic devices and machines for facilitating cipher operations have been known for many years; they vary in com plexity from simple, superimposed, concentrically or eccentrically rotating disks to large, mechanically or electrically operated type writing and telegraph apparatus suitably modified for crypto graphic purposes. One of the best cryptographs of the more simple, mechanical type is that known as the Bazeries cylinder, named after the Frenchman who is commonly credited with its invention in 1891. The principle upon which the device is based was, however, conceived many years before by Thomas Jefferson (see Jefferson's Papers, Vol. 232, item 41,575). The Bazeries cylinder consists of a set of 20 disks, each bearing on its periphery a different mixed alphabet. The disks, which bear identifying numbers from 1 to 20, are assembled upon a common shaft from left to right according to a numerical key. In encipherment the disks are revolved so as to bring the plain-text letters on a single horizontal line, and then the letters of any other horizontal line are taken as the cipher equivalents. The text is thus enciphered 20 letters at a time. In deciphering, the cipher letters are "set up" upon one horizontal line by revolving the disks and locking them into position. By slowly revolving the whole cylinder and examining each horizontal line, only one of the latter will be found to yield intelligible text. One of the most ingenious of the more complicated types of cipher machines is that embodied in certain printing telegraph apparatus of modern design. In this system electrical encipherment, transmission, reception and decipherment, controlled by perforated tapes, may be accomplished simultane ously at a high rate of speed. Of the many devices and machines that have been invented, constructed and marketed, only a re markably small number have ever been, or are now, in use. In general, the degree of secrecy afforded by the types heretofore constructed is not sufficiently high to warrant their adoption for diplomatic, naval or military telegraphic correspondence; and the fact that in international correspondence the cost of transmitting telegrams in cipher language (unpronounceable groups) has for over a quarter of a century been twice that for telegrams in code language (pronounceable groups) has constituted an effective de terrent to the use of cipher machinery in commercial telegraphic correspondence.

Code Systems.

These are simple but highly specialized forms of substitution systems, and the most important developments in them since the advent of electromagnetic telegraphy have always been either American or British in origin. They merely involve the use of modified conventional dictionaries termed code books, by means of which textual units of variable length—usually whole words, phrases and sentences—can be replaced by arbitrarily as signed signals termed code groups. From the point of view of practical usage today, code systems are more important than cipher systems, their simplicity and economy constituting their chief advantages. In encoding a message it is necessary merely to refer to the code book, find the desired words, phrases, sen tences, numbers, etc., and replace them by the code groups assigned them, building the message up step by step in the fewest code groups possible. The condensing power of codes, brought about by the fact that a single code group may represent a long word, a phrase, or a complete sentence, depends upon the extent of the code and the skill used in its compilation ; an average con densation of i :5 (that is, one code group replacing five plain-text words) is quite common in commercial codes. The older types of codes employed either dictionary words or figure groups as code equivalents, but since 1904 such codes have been almost com pletely superseded by codes employing five-letter groups con structed by means of elaborate permutation tables. The most important feature of such a table is that it facilitates the construc tion of a series of i oo,000 or more five-letter, pronounceable, arti ficial "words," all of which differ from one another in at least two letters. For example, if BERAM is a bona fide member of a given series, there will not be present in the same series any group differing from BERAM in only a single letter, such as CERAM, BIRAM, BESAM, BERIM, BERAN, etc. In the latest codes an additional safeguard has been incorporated, having as its object the suppression of errors introduced by the accidental transposi tion of adjacent letters in a code group. For example, if BERAM is a bona fide member of a given series, there will not be present in the same series any of the following groups: EBRAM, BREAM, BEARM, BERMA. In some codes an attempt is made to sup press errors introduced by the accidental transpositions of alternate letters as well as adjacent letters. These features, though of com paratively recent origin, are very important in that they have greatly increased the accuracy of code communication. The natural evolution of code words and code language has been to some extent guided by regulations drawn up from time to time by international telegraph conferences.

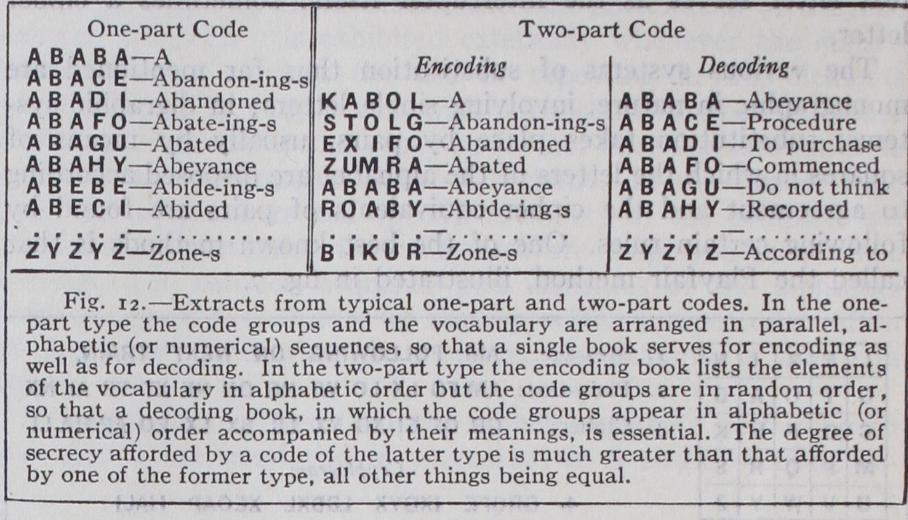

The principal purpose of code in commerce is to effect economy, secrecy being usually of secondary importance (except in banking operations) ; in governmental affairs, however, the situation is exactly reversed. A code system is secret or nonsecret, depending upon the distribution and construction of the code book, and upon whether or not it is used in conjunction with a superimposed cipher system. Codes for general business correspondence are purchasable from their publishers and therefore provide in them selves no secrecy. Many business firms, however, have private codes which, if carefully restricted in distribution, may constitute codes that may be regarded as secret except to experts. Govern mental codes are, of course, very carefully guarded in their production, distribution and usage. As to their construction, codes may be of the "one-part" or the "two-part" type, the principal difference between them being shown in fig. 12.

When the code words of a simple code message undergo en cipherment by a superimposed cipher system the result is termed enciphered code. Its purpose is to afford secrecy, in the case of purchasable commercial codes, or additional secrecy, in the case of private or governmental codes. The superimposition of a suitable cipher system upon code text prepared by means of an extensive two-part code imparts an exceedingly high degree of secrecy to messages and constitutes a practical system much in use by large governments for voluminous correspondences.

The science of solving cryptograms by analysis, having under gone great development in recent years, has been deemed worthy of being designated by a special name, cryptanalysis, to distinguish the indirect methods of reading cryptograms from the much more direct methods, called deciphering and decoding, which imply a knowledge of the basic method and specific key, in the case of ciphers, or possession of the code book, in the case of codes. Apart from the more simple, classical types, nearly every scientif ically constructed cryptographic system presents a unique case in cryptanalysis, the unraveling of which requires the exercise of unusual powers of inductive and deductive reasoning, much concentration, perseverance and a vivid imagination; but all these qualities are of little avail without a special aptitude based upon extensive, practical experience. A preliminary requisite to the analysis of a cryptogram is a determination of the language in which its plain text is written, information which is either already at hand in the case of official correspondence, or which, in the case of private correspondence, can usually be obtained from extraneous circumstances. Next comes a determination as to whether a cipher or a code system is involved ; this is based upon the fact that differences in their external appearance are usually sufficiently well marked to be detectable by experts. If the cryptogram is in cipher, the next step is to determine whether it belongs to the transposition or to the substitution class. This determination rests upon the fact that in plain text the vowels and consonants are present in definite proportions. Since trans position involves only a rearrangement of the original letters, it follows that if a cryptogram contains vowels and consonants in the approximately normal proportions it is of the transposition class; if not, it is of the substitution class. The solution of trans position ciphers involves much experimentation with geometrical designs of various types and dimensions, clues to which are afforded by the number of letters in the messages and extraneous circumstances. The assumption of the presence of probable words is often necessary. Special methods of solution based upon a study of messages of identical lengths, or with identical beginnings or endings, are often possible to apply when much traffic has been intercepted. Finally, the presence of letters which in dividually are of low frequency, but which when present have a great affinity for each other and form pairs of moderate or high frequency, such as QU in Spanish, or CH in German, afford clues leading to solution.

The basis upon which the solution of practically all substitution ciphers rests is the well-known fact that every written alphabetic language manifests a high degree of constancy in the relative fre quencies with which its individual letters are employed. For ex ample, English telegraphic text shows the following relative fre quencies in I.000 letters, based upon an actual count of Ioo,000 letters appearing in telegrams of a commercial and military nature.

These characteristic relative frequencies serve as a basis for identifying the plain-text values of the cipher letters, but only when the cipher has been reduced to the simple terms of a single alphabet. Thus, the problem of solving a monoalphabetic sub stitution cipher involves only one step, since the text is already in the simplest possible terms, but the problem of solving a polyalphabetic substitution cipher involves three principal steps: first, determining the number of cipher alphabets involved; second, distributing the cipher letters to the respective mono alphabetic frequency tables to which they belong; third, analyzing each of the latter on the basis of normal frequencies in plain text. In the case of ciphers exhibiting periodicity, the cyclic phenomena are employed in determining the number of alphabets involved, as well as in distributing each cipher letter to the monoalphabetic frequency table to which it belongs. In the case of aperiodic ciphers, because of the absence of cyclic phenomena, both of these steps are often very difficult, especially when the volume of text is limited. Frequently the only recourse is to employ repetitions as a basis for superimposing separate messages so that, irrespective of the number of alphabets involved, or their sequence, the letters pertaining to identical cipher alphabets fall into the same columns, and then the separate columns are treated as monoalphabetic frequency tables. The analysis of the frequency distributions of a polyalphabetic cipher is effected much more readily when the alphabets are interrelated than when they are independent.

The question as to whether an absolutely unsolvable cipher system can be devised is of more interest to laymen than to pro fessional cryptographers. Edgar Allan Poe's dictum that "it may be roundly asserted that human ingenuity cannot concoct a cipher which human ingenuity cannot resolve" is misleading unless qualified by restricting its application to the great majority of the practical systems employed for a voluminous, regular correspond ence. For isolated, short cryptograms prepared by certain methods may resist solution indefinitely ; and there is at least one cipher system which may be mathematically demonstrated as being absolutely unsolvable without the specific key, even though the basic method be completely known.