Coffee

COFFEE. This important and valuable article of food is the produce chiefly of Co$ea arabica, a Rubiaceous plant indigenous to Abyssinia, which, however, as cultivated originally, spread out wards from the southern parts of Arabia. The name is probably derived from the Arabic K'hawah, although by some it has been traced to Kaffa, a province in Abyssinia, in which the tree grows wild.

The genus Coffea, to which the common coffee tree belongs, contains about 25 species in the tropics of the Old World, mainly African. Besides being found wild in Abyssinia, the common coffee plant appears to be widely disseminated in Africa, occurring wild in the Mozambique district, on the shores of the Victoria Nyanza, and in Angola on the west coast. The coffee leaf disease in Ceylon brought into prominence a Liberian coffee (C. liberica), a native of the west coast of Africa, now extensively grown in several parts of the world. Other species of economic importance are Sierra Leone coffee (C. stenophylla) and Congo coffee (C. robusta), both of which have been introduced into and are culti vated on a small scale in various parts of the tropics. C. excelsa is another species of considerable promise.

The common Arabian coffee shrub is an evergreen plant, which under natural conditions grows to a height of from 18 to 20 ft., with oblong-ovate, acuminate, smooth and shining leaves, measur ing about 6in. in length by 2 tin. wide. Its flowers, which are pro duced in dense clusters in the axils of the leaves, have a five toothed calyx, a tubular five-parted corolla, five stamens and a single bifid style. The flowers are pure white in colour, with a rich fragrant odour, and the plants in blossom have a lovely and attractive appearance, but the bloom is very evanescent. The fruit is a fleshy berry, having the appearance and size of a small cherry, and as it ripens it assumes a dark red colour. Each fruit contains two seeds embedded in a yellowish pulp, and the seeds are enclosed in a thin membranous endocarp (the "parchment"). Between each seed and the parchment is a delicate covering called the "silver skin." The seeds which constitute the raw coffee "beans" of commerce are plano-convex in form, the flat surfaces which are laid against each other within the berry having a longitudinal furrow or groove.

When only one seed is developed in a fruit it is not flattened on one side, but circular in cross section.

Such seeds form "pea-berry" cof f ee, The seeds are of a soft, semi translucent, bluish or greenish colour, hard and tough in texture.

The regions best adapted for the cultivation of coffee are well watered mountain slopes at an elevation ranging from i,000 to 4,0ooft. above sea-level, within the tropics, and possessing a mean annual temperature of about 65° to 7o° F.

The Liberian coffee plant (C.

liberica) has larger leaves, flow er:. and fruits, and is of a more robust and hardy constitution than Arabian coffee. The seeds yield a highly aromatic and well flavoured coffee (but by no means equal to Arabian), and the plant is very prolific and yields heavy crops. Liberian coffee grows, moreover, at low altitudes, and flourishes in many situations un suitable to the Arabian coffee.

It grows wild in great abun dance along the whole of the Guinea coast.

History of Coffee.

The early history of coffee as an economic product is involved in considerable obscurity, the absence of fact being compensated for by a profusion of conjectural statements and mythical stories. The use of coffee (C. arabica) in Abyssinia was recorded in the i 5th century, and was then stated to have been practised from time immemorial. Neighbouring countries, however, appear to have been quite ignorant of its value. Its physiological action in dissipating drowsiness and preventing sleep was taken advantage of in connection with the prolonged religious service of the Mohammedans, and its use as a devotional antisoporific stirred up fierce opposition on the part of the strictly orthodox and conservative section of the priests. Coffee by them was held to be an intoxicating beverage, and therefore prohibited by the Koran, and severe penalties were threatened to those addicted to its use. Notwithstanding, the coffee-drinking habit spread rapidly among the Arabian Mohammedans, and the growth of coffee and its use as a national beverage became as inseparably connected with Arabia as tea is with China.The appreciation of coffee as a beverage in Europe dates from the 17th century. "Coffee-houses" were soon instituted, the first being opened in Constantinople and Venice. In London coffee houses date from 1652, when one was opened in St. Michael's Alley, Cornhill. They soon became popular, and the role played by them in the social life of the 17th and 18th centuries is well known. In Europe, as in Arabia, coffee at first made its way into favour in the face of various adverse and even prohibitive restric tions. Thus at one time in Germany it was necessary to obtain a licence to roast coffee. In England Charles II. endeavoured to suppress coffee-houses on the ground that they were centres of political agitation.

Up to the close of the 17th century, the world's entire, although limited, supply of coffee was obtained from the province of Yemen in south Arabia, where the true celebrated Mocha or Mokka cof fee is still produced. At this time, however, plants were success fully introduced from Arabia to Java, where the cultivation was immediately taken up. The government of Java distributed plants to various places, including the botanic garden of Amsterdam. The Portuguese introduced coffee into Ceylon. From Amsterdam the Dutch sent the plant to Surinam in 1718, and in the same year Jamaica received it through its governor, Sir Nicholas Lawes, whence it spread generally through the tropics of the New World, which now produce by far the greater portion of the world's supply.

Cultivation and Preparation for Market.

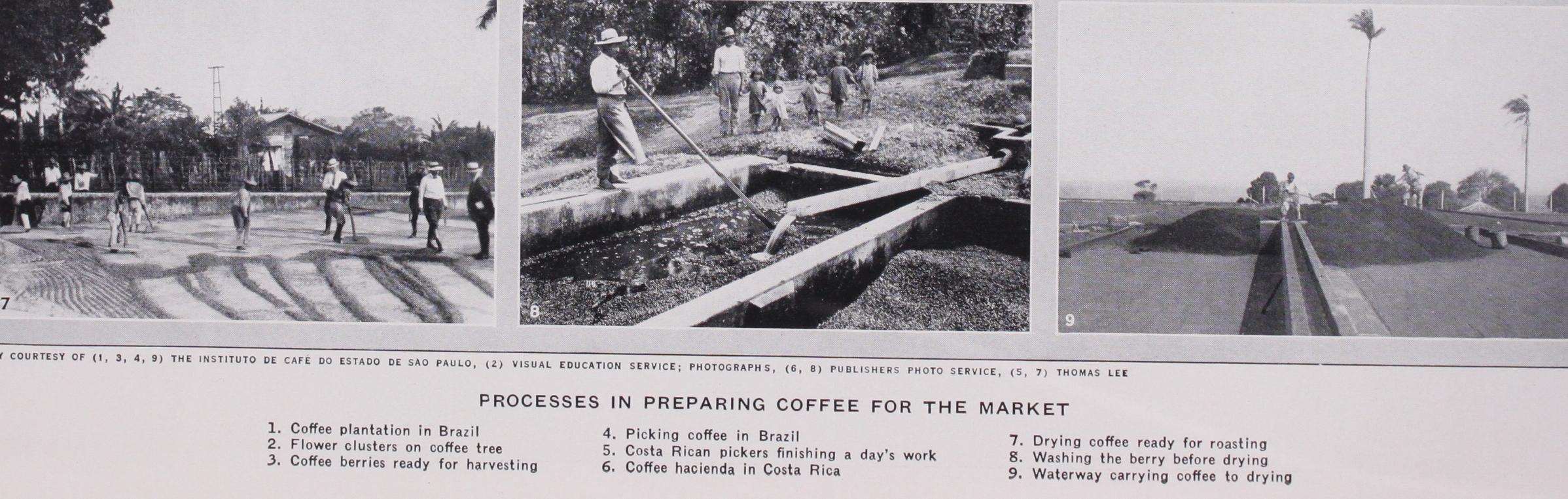

Coffee plants are grown from seeds, which, as in the case of other crops, should be obtained from selected trees of desirable characteristics. The seeds may be sown "at stake," i.e., in the actual positions the ma ture plants are to occupy, or raised in a nursery and afterwards transplanted. The choice of methods is usually determined by various local considerations. Nurseries are desirable where there is risk of drought killing seedlings in the open. Whilst young the plants usually require to be shaded, and this may be done by growing castor oil plants, cassava (Manihot), maize or Indian corn, bananas, or various other useful crops between the coffee, until the latter develop and occupy the ground. Sometimes, but by no means always, permanent shading is afforded by special shade trees, such as species of the coral tree (Erythrina) and other leguminous trees. Opinions as to the necessity of shade trees varies in different countries.The plants begin to come into bearing in their second or third year, but on the average the fifth is the first year of considerable yield. There may be two, three, or even more "flushes" of blos som in one year, and flowers and fruits in all stages may thus be seen on one plant. The fruits are fully ripe about seven months after the flowers open; the ripe fruits are fleshy, and of a deep red colour, whence the name of "cherry." When mature the fruits are picked by hand, or allowed to fall of their own accord or by shaking the plant. The subsequent preparation may be ac cording to (I) the dry or (2) the wet method.

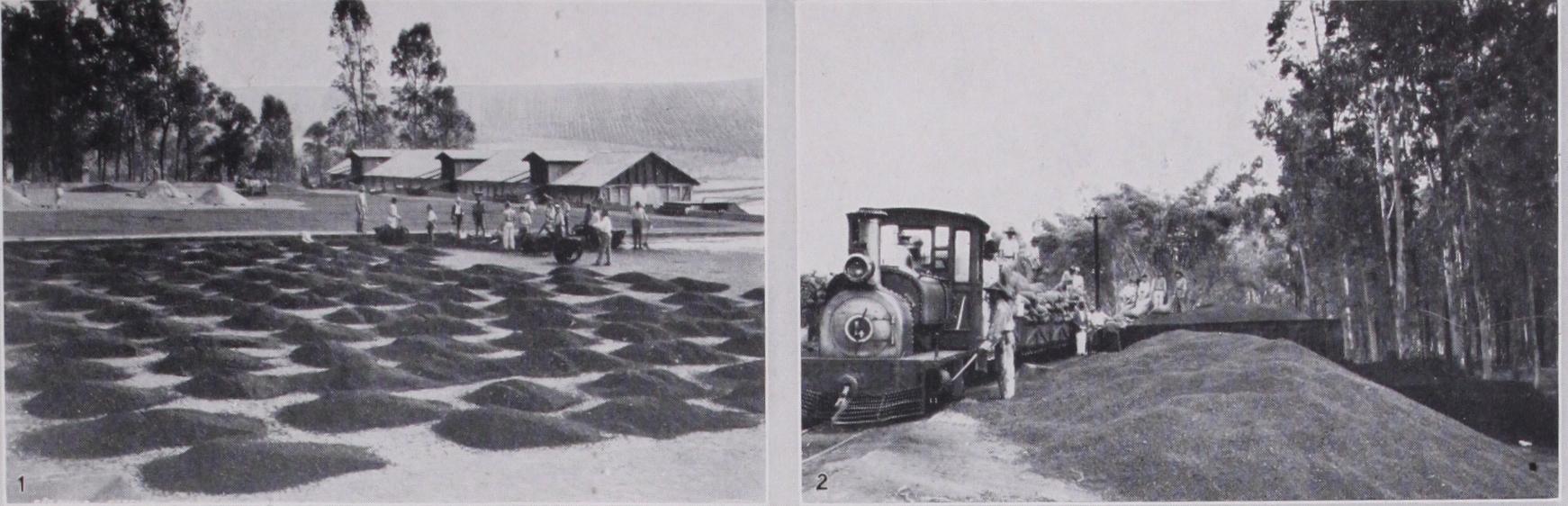

In the dry method the cherries are spread in a thin layer, often on a stone drying floor, or barbecue, and exposed to the sun. Pro tection is necessary against heavy dew or rain. The dried cherries can be stored for any length of time, and later the dried pulp and the parchment are removed, set ting free the two beans contained in each cherry. This primitive and simple method is employed in Arabia and other countries; in Brazil it has largely given place to the more modern method de scribed below.

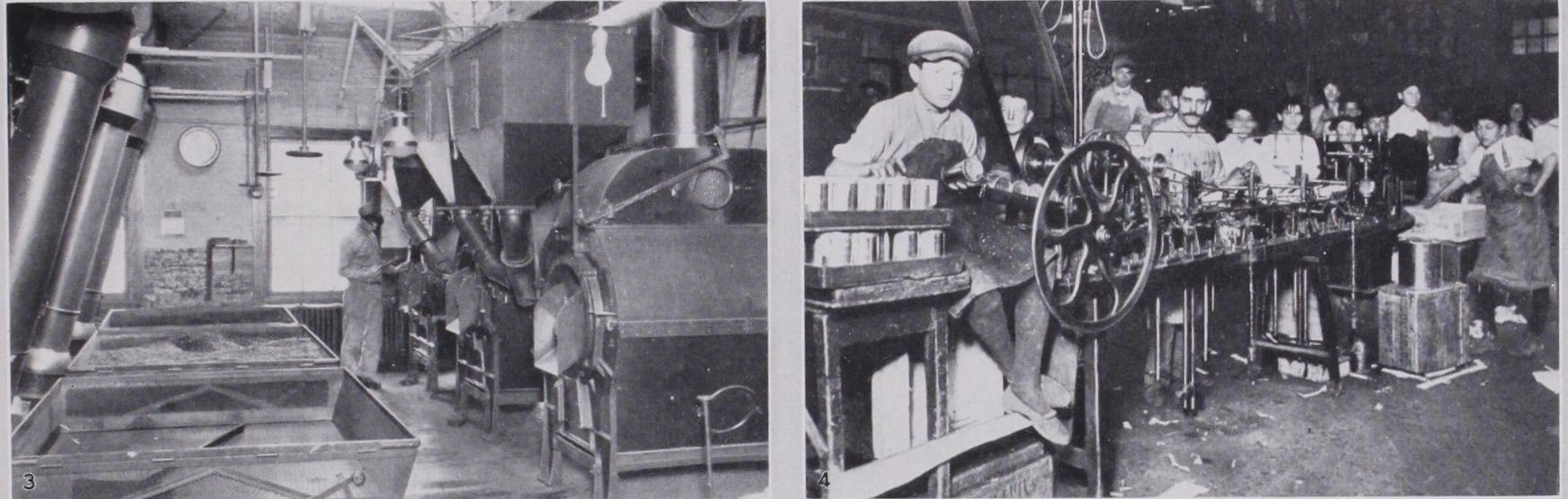

In the wet, or as it is times called, West Indian method, the cherries are put in a tank of water. On large estates galvanized spouting is often ployed to convey the beans by the help of running water from the fields to the tank. The ture cherries sink, and are drawn off from the tank through pipes to the pulping machines. Here they are subjected to the action of a roughened der revolving closely against a curved iron plate. The fleshy portion is reduced to a pulp and the mixture of pulp and ated seeds (each still enclosed in its parchment) is carried away to a second tank of water and stirred. The light pulp is moved by a stream of water and the seeds allowed to settle. Slight fermentation and subsequent washings, accompanied by trampling with bare feet and stirring by rakes or special machinery, result in the parchment coverings being left quite clean. The beans are now dried on barbecues, in trays, etc., or by artificial heat if matic conditions render this necessary. Experiments in Porto Rico tend to show that if the weather is unfavourable during the crop period the pulped coffee can be allowed to remain moist and even to malt or sprout without injury to the final value of the product when dried later. The product is now in the state known as parchment coffee, and may be exported. Before use, how ever, the parchment must be removed. This may be done on the estate, at the port of shipment, or in the country where im ported. The coffee is thoroughly dried, the parchment broken by a roller, and removed by winnowing. Further rubbing and win nowing removes the silver skin, and the beans are left in the con dition of ordinary unroasted coffee. Grading into large, medium and small beans, to secure the uniformity desirable in roasting, is effected by the use of a cylindrical or other pattern sieve, along which the beans are made to travel, encountering first small, then medium, and finally large apertures or meshes. Damaged beans and foreign matter are removed by hand picking. An average yield of cleaned coffee is from z to 2 lb. per tree, but much greater crops are obtained on new rich lands, and under special conditions.

Coffee-leaf Disease.

The coffee industry in Ceylon was ruined by the attack of a fungoid disease (Hemileia vastatrix) known as the Ceylon coffee-leaf disease. This has since extended its ravages into every coffee-producing country in the Old World, and added greatly to the difficulties of successful cultivation. The fungus is a microscopic one the minute spores of which, car ried by the wind, settle and germinate upon the leaves of the plant. The fungal growth spreads through the substance to the leaf, robbing the leaf of its nourishment and causing it to wither and fall. An infected plantation may be cleansed, and the fungus in its nascent state destroyed, by powdering the trees with a mix ture of lime and sulphur, but, unless the access of fresh spores brought by the wind can be arrested, the plantations may be read ily reinfected when the lime and sulphur are washed off by rain. The separation of plantations by belts of trees to windward is suggested as a check to the spread of the disease.

Microscopic Structure.

Raw coffee seeds are tough and horny in structure, and are devoid of the peculiar aroma and taste which are so characteristic of the roasted seeds. The minute structure of coffee allows it to be readily recognized by means of the microscope, and as roasting does not destroy its distinguish ing peculiarities, microscopic examination forms the readiest means of determining the genuineness of any sample. The sub stance of the seed, according to Dr. Hassall, consists "of an as semblage of vesicles or cells of an angular form, which adhere so firmly together that they break up into pieces rather than separate into distinct and perfect cells. The cavities of the cells include, in the form of little drops, a considerable quantity of aromatic vol atile oil, on the presence of which the fragrance and many of the active principles of the berry depend." Physiological Action.—Coffee belongs to the medicinal or auxiliary class of food substances, being solely valuable for its stimulant effect upon the nervous and vascular system. It pro duces a feeling of buoyancy and exhilaration comparable to a cer tain stage of alcoholic intoxication, but which does not end in de pression or collapse. It increases the frequency of the pulse, lightens the sensation of fatigue, and it sustains the strength under prolonged and severe muscular exertion. The value of its hot infusion under the rigours of Arctic cold has been demonstrated in the experience of all Arctic explorers, and it is scarcely less useful in tropical regions, where it beneficially stimulates the action of the skin.The physiological action of coffee mainly depends on the pres ence of the alkaloid caffeine, which occurs also in tea, Paraguay tea, and cola nuts, and is very similar to theobromine, the active principle in cocoa. The percentage of caffeine present varies in the different species of Coffea. In Arabian coffee it ranges from about 0.7 to 1.6%; in Liberian coffee from i•o to 1.5%. Sierra Leone coffee (C. stenophylla) contains from 1.52 to 1•70%; in C. excelsa 1.89% is recorded, and as much as 1.97% in C. canephora. Four species have been shown by M. G. Bertrand to contain no caffeine at all, but instead a considerable quantity of a bitter prin ciple. All these four species are found only in Madagascar or the neighbouring islands. Other coffees grown there contain caffeine as usual. Coffee, with the caffeine extracted, has also been pre pared for the market. The commercial value of coffee is deter mined by the amount of the aromatic oil, caffeone, which develops in it by the process of roasting. By prolonged keeping it is found that the richness of any seeds in this peculiar oil is increased, and with increased aroma the coffee also yields a blander and more mellow beverage. Stored coffee loses weight at first with great rapidity, as much as 8% having been found to dissipate in the first year of keeping, 5% in the second, and 2% in the third; but such loss of weight is more than compensated by improvement in quality and consequent enhancement of value.

Coffee Roasting.

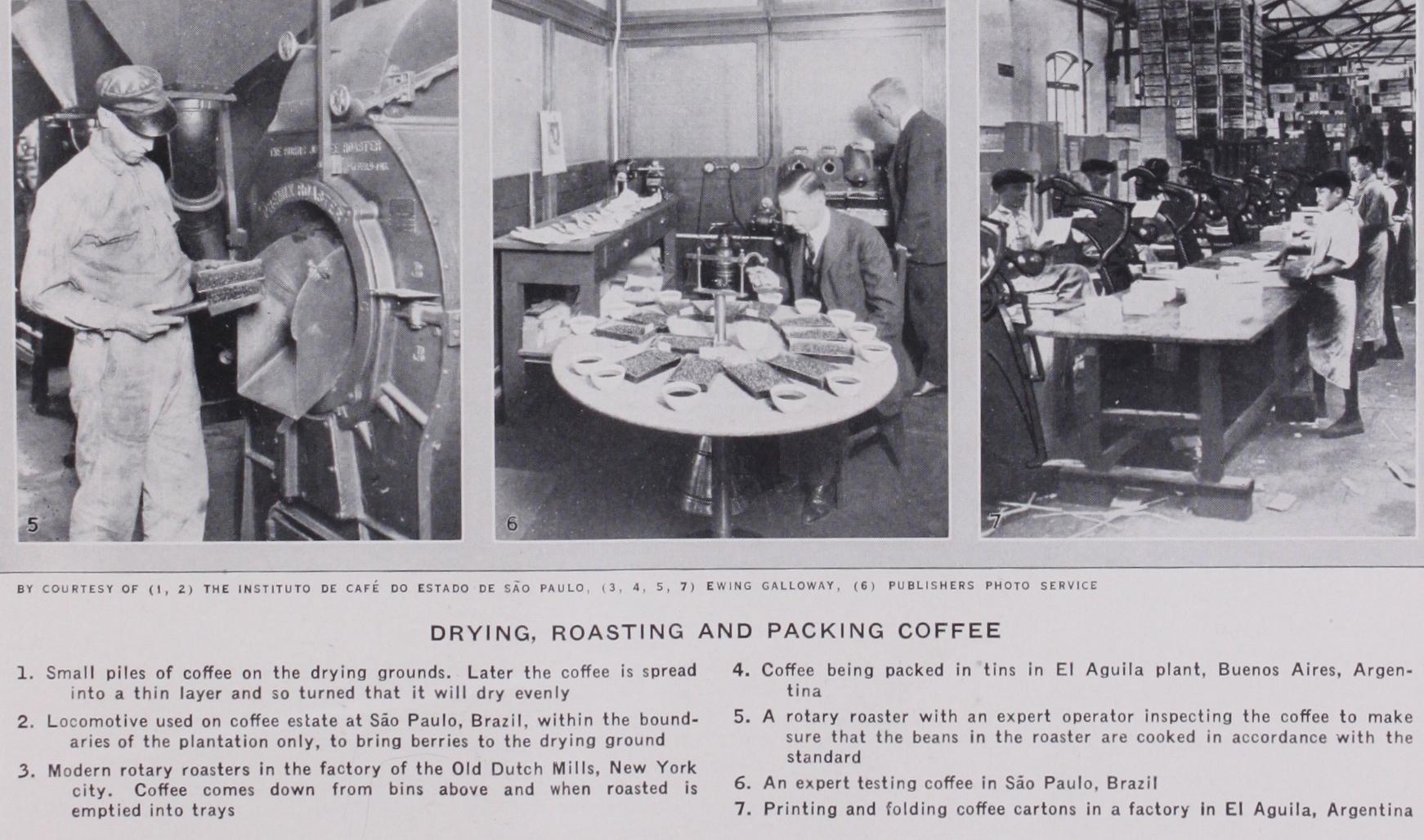

In the process of roasting, coffee seeds swell up by the liberation of gases within their substance,—their weight decreasing in proportion to the extent to which the operation is carried. Roasting also develops with the aromatic caffeone to a bitter soluble principle, and it liberates a portion of the caffeine from its combination with the caffetannic acid. Roasting is an op eration of the greatest nicety, and one, moreover, of a crucial nature, for equally by insufficient and by excessive roasting much of the aroma of the coffee is lost ; and its infusion is neither agree able to the palate nor exhilarating in its influence. The roaster must judge of the amount of heat required for the adequate roast ing of different qualities, and while that is variable, the range of roasting temperature proper for individual kinds is only narrow. In continental countries it is the practice to roast in small quan tities, and thus the whole charge is well under the control of the roaster; but in Britain large roasts are the rule, in dealing with which much difficulty is experienced in producing uniform torre faction, and in stopping the process at the proper moment. The coffee-roasting apparatus is usually a malleable iron cylinder mounted to revolve over the fire on a hollow axle which allows the escape of gases generated during torrefaction. The roasting of coffee should be done as short a time as practicable before the grinding for use, and as ground coffee especially parts rapidly with its aroma, the grinding should only be done when coffee is about to be prepared.

Coffee Adulteration.

Although by microscopic, physical and chemical tests the purity of coffee can be determined with perfect certainty, yet ground coffee is subjected to many and extensive adulterations (see also ADULTERATION). Chief among the adul terant substances, if it can be so called, is chicory; but it occu pies a peculiar position, since very many people on the European continent as well as in Great Britain deliberately prefer a mix ture of chicory with coffee to pure coffee. Chicory is indeed des titute of the stimulant alkaloid and essential oil for which coffee is valued; but the facts that it has stood the test of prolonged and extended use, and that its infusion is, in some localities, used alone, indicate that it performs some useful function in connec tion with coffee, as used at least by Western communities. For one thing, it yields a copious amount of soluble matter in infusion with hot water, and thus gives a specious appearance of strength and substance to what may be really only a very weak preparation of coffee. The mixture of chicory with coffee is easily detected by the microscope, the structure of both, which they retain after torrefaction, being very characteristic and distinct. The granules of coffee, moreover, remain hard and angular when mixed with water, to which they communicate but little colour; chicory, on the other hand, swelling up and softening, yields a deep brown colour to water in which it is thrown. The specific gravity of an infusion of chicory is also much higher than that of coffee. Among Ale numerous other substances used to adulterate coffee are roasted and ground roots of the dandelion, carrot, parsnip and beet ; beans, lupins and other leguminous seeds; wheat, rice and various cereal grains; the seeds of the broom, fenugreek and iris; acorns; "negro coffee," the seeds of Cassia occidentalis, the seeds of the ochro (Hibiscus esculentus), and also the soja or soy bean (Glycine Soya). Not only have these with many more similar substances been used as adulterants, but under various high-sounding names several of them have been introduced as substitutes for coffee. But also, not only is ground coffee adulterated, but such mixtures as flour, chicory and coffee, or even bran and molasses, have been made up to simulate coffee beans and sold as such.The leaves of the coffee tree contain caffeine in larger propor tion than the seeds themselves, and their use as a substitute for tea has frequently been suggested. The leaves are actually so used in Sumatra, but being destitute of any attractive aroma such as is possessed by both tea and coffee, the infusion is not palatable. It is moreover, not practicable to obtain both seeds and leaves from the same plant, and as the commercial demand is for the seed alone, no consideration either of profit or of any dietetic or economic advantage is likely to lead to the growth of coffee trees on account of their leaves. (A. B. R. ; W. G. F.) Coffee Production.—The centre of production has shifted greatly since coffee first came into use in Europe. Arabia formerly supplied the world; later the West Indies and then Java took the lead, to be supplanted in turn by Brazil, whose output is of over whelming importance. Coffee is Brazil's main industry and main export .

Brazil.

The importance of Brazil in coffee production is shown by her annual production which is about two-thirds of the world's supply. During the crop year 1926-27 the production of coffee in Brazil amounted to 21,252,000 bags of 6o kilo. each. Other countries sent to Europe and the United States 7,068,000 bags. The world's visible supply of all kinds on July 1, 1927, consisted of 4,418,000 bags of which 3,262,00o were stored in Brazil. The protection of the crop is under the control of the Sao Paulo institute for the permanent defence of coffee, the Fed eral Government having relinquished in its favour all rights con ferred by law.The law of the State of Sao Paulo provides that the chairman and the vice-chairman of this body shall be its ministers of Finance and of Agriculture respectively, the three remaining members of the governing body being elected by the two associations of planters and the commercial association of Santos, subject to the approval of the president of the State. The powers of the institute include the regulation of the amount of coffee to be retained in the official warehouses through which all coffee produced in the interior must pass; io of these had been erected throughout the coffee-growing districts of Sao Paulo and one in the State of Rio, their total capacity being 11,500,000 bags per annum. Other powers of the institute extend to the amount of coffee to be ex ported, the making of agreements with other producing countries for the protection of coffee, the concluding of financial arrange ments, the levying of an export tax on coffee, and the establish ment of an agricultural loan bank. To obtain funds for the insti tute £4,000,000 of 71% bonds were issued in London and f 00o in Holland and Switzerland in Jan. 1926. Interest on this capital is to be raised by a transport tax of one gold milreis (2s. 3d.) levied on each bag of coffee grown in and transported through the State of Sao Paulo.

The effects of the "permanent defence of coffee" in the United States, Brazil's greatest customer, were higher prices and reduced consumption. In June and July 1925, a mission from the United States, consisting of three representatives of the trade in coffee, visited the institute and the producing centres in Brazil. After conference, the following measures were agreed: the daily regu lated entry into Santos of coffee for export in accordance with the crops and the needs of consumption; the maintenance of a stock in Santos of never less than 1,200,000 bags, to facilitate the buyers finding the qualities required; the constant attendance of American buyers on the Santos market ; full publication of sta tistics and of data relative to crops, stocks, etc. ; and the resump tion of coffee-propaganda in the United States. It was also ar ranged that similar conferences should be held in 1926 and annu ally thereafter. (See BRAZIL.) Other South American Producers.—Next in importance to Brazil as a coffee-growing country, Colombia showed signs of fol lowing her example. A law providing for the establishment of coffee bonded warehouses and the official classification of coffee, with the issue of negotiable bonds, was passed, but the declared policy of the Government was to help the industry without inter fering with prices. Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, and to a much less degree Bolivia and Paraguay also produce coffee.

West Indies.

Coffee is grown in most of the islands, often only for local use; Haiti produces the largest amount. Jamaica produces the famous Blue Mountain Coffee, which compares favourably with the best coffees of the world, and also ordinary or "plain grown." East Africa.—Coffee growing under British auspices in Kenya has rapidly developed. In 1920 there were 27,813ac. under coffee; on July 31, 1926, there were 68,95oac. The production in 1926-7 was 161,498cwt. The exports from Mombasa in 1925-6 were valued at £771,830. The colony also had 22,888ac. planted with trees less than three years old, which had not come into full bearing. On the London market Nairobi and Uganda cof fees now appear as Kenya. Africa, of course, is the native country of the coffees and may eventually become the greatest world producer.

Arabia.

The name "Mocha" is applied generally to coffee produced in Arabia. Turkey and Egypt obtain the best grades. Traders from these countries go to Arabia, buy the crops on the trees, and supervise its picking and preparation themselves. The coffee is prepared by the "dry method." India.—India is the principal coffee-growing region in the Brit ish empire, and exports largely to the United Kingdom. The pro duction of coffee is restricted for the most part to a limited area in the elevated region above the south-western coast, the coffee lands of Mysore, Coorg, and the Madras districts of Malabar and the Nilgiris, comprising 86% of the whole area under the plant in India. About one-half of the whole coffee-producing area is in Mysore.

Coffee Exports.

The following table shows the exports of coffee from the principal producing countries during the last sta tistical year of which record is available, 1927:— Coffee Consumption.—The annual British consumption of coffee remains stationary at about 0.7 lb. per capita. British taste in coffee is satisfied largely with the produce of the Central Ameri can Republic of Costa Rica; the demand for the produce of Kenya Colony is increasing. In Sept. 1915 the British import duty on raw coffee was increased from 14s. to 21s. per cwt. and again to in 1916. On Sept. 1, 1919 the duties became 42s. on foreign grown, and 35s. on that from British possessions. Later changes were: in 1922, 285. and 23s. 4d. ; and in 1924, 145. and I is. 8d.Annual consumption in the United States rose from I r lb. per capita before the World War to 12.4 lb. in 1923 : in 1925 it had fallen to '14)9 lb. About two thirds of the imports in 1925 came from Brazil and the greater part of the remainder from Colombia.

(C. L. T. B.)