Coffin

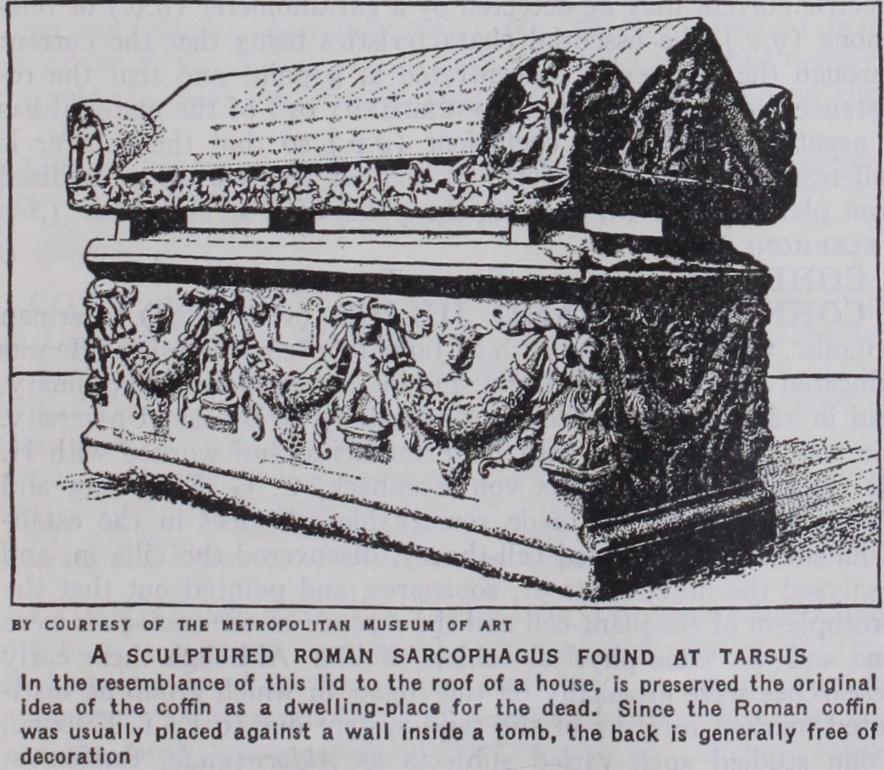

COFFIN, the receptacle in which a corpse is confined (Lat. cophinus, a coffer, chest or basket, but not "coffin" in its present sense). The Greeks and Romans disposed of their dead both by burial and by cremation. Greek coffins varied in shape, being in the form of an urn, or like the modern coffins, or triangular, the body being in a sitting posture. The material used was generally burnt clay, and in some cases this had obviously been first moulded round the body, and so baked. In the Christian era, stone coffins came into use. Examples of these have been frequently dug up in England. Those of the Romans who were rich enough had their coffins made of a limestone brought from Assos in Troas, which it was commonly believed "ate the body"; hence arose the name sarcophagus (q.v.).

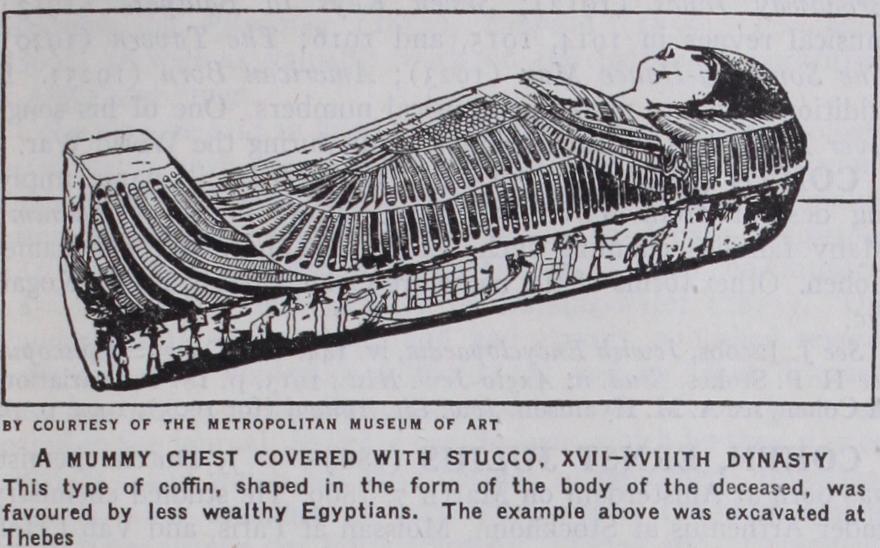

The coffins of the Chaldaeans were generally clay urns with the top left open, resembling immense jars, moulded round the body, as the size of the mouth would not admit of its introduction after the clay was baked. The Egyptian coffins, or sarcophagi, as they have been improperly called, are the largest stone coffins known and are generally highly polished and covered with hieroglyphics, usually a history of the deceased. Mummy chests shaped to the form of the body were also used, being made of hard wood or papier mache painted, and bore hieroglyphics. Unhewn flat stones were sometimes used by early European peoples to line the grave. One was placed at the bottom, others stood on their edges to form the sides, and a large slab was put on top, thus forming a rude cist. In England after the Roman invasion these rude cists gave place to the stone coffin which was used until the 16th century.

Primitive wooden coffins were formed of a tree-trunk split down the centre, and hollowed out—a type still in use among peoples in the lower culture. The earliest specimen of this type is in the Copenhagen museum, the implements found in it proving that it belonged to the Bronze Age. This type of coffin, more or less modified by planing, was used in mediaeval Britain by those who could not afford stone, while the poor were buried without coffins, wrapped simply in cloth or even covered only with hay and flowers. Towards the end of the 17th century, coffins became usual for all classes.

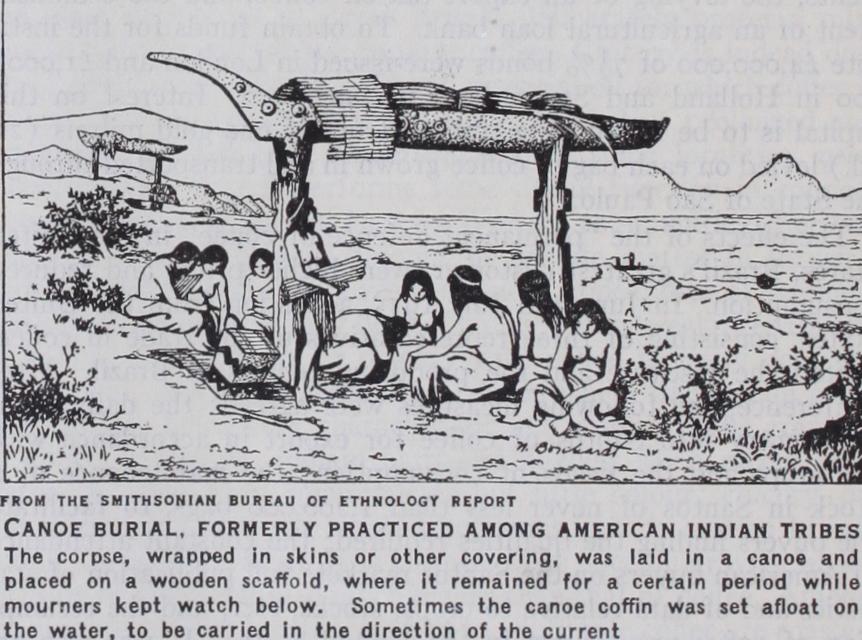

Among the American Indians some tribes, e.g., the Sacs, Foxes and Sioux, used rough hewn wooden coffins; others, such as the Seris, sometimes enclosed the corpse between the carapace and plastron of a turtle. The Seminoles of Florida used no coffins, while at Santa Barbara, California, canoes containing corpses have been found buried, though they may have been intended for the dead warrior's use in the next world. Rough stone cists, too, have been found in Illinois and Kentucky. In their tree and scaffold burial the Indians sometimes used wooden coffins or travois baskets, or the bodies were simply wrapped in blankets. Canoes, mounted on a scaffold, near a river, were used as coffins by some tribes; while others placed the corpse in a canoe or wicker basket and floated it out into the stream or lake. The aborigines of Australia generally used coffins of bark, but some tribes em ployed baskets of wicker-work.

Lead coffins were used in Europe in the middle ages, shaped like the mummy chests of ancient Egypt. Iron coffins were certainly used in England and Scotland as late as the 17th century. The coffins used in England to-day are generally hexagonal in shape, of elm or oak lined with lead, or with a leaden shell. In America glass is sometimes used for the lids, and the inside is lined with copper or zinc. The coffins of France and Germany and the Con tinent in general usually have sides and ends parallel. Coffins used in cremation throughout the civilized world are of some light material easily consumed and yielding little ash. Ordinary thin deal and papier mdche are the favourite materials. Coffins for what is known as Earth to Earth Burial are made of wicker-work covered with a thin layer of papier mdche over cloth.