Making the Ware

MAKING THE WARE The "Slip."—The "slip," it should be explained, is the china clay and other ingredients mixed with water to a thin consistency. Metallic impurities, which would spoil the finished ware, are re moved by a series of magnets, which, in one method, are arranged in what is known as a "cascade," i.e., the watery mass flows over small falls, the metallic parts being retained by the magnets and the remainder passing on. As the "slip" has to pass over a series of small falls in cascade fashion, any pieces of metal are certain to be extracted. (Prior to this process the various ingredients have been weighed and mixed in an agitator known as a "blunger.") The "slip" is, of course, too thin in consistency for moulding into ware, and must be made into a firm and plastic condition. This is done in a filter press, an appliance used in many trades. Briefly, this consists of a number of cloth bags in square frames, which are screwed together horizontally, the whole resembling a "square" loaf, cut into slices, but retaining the shape of the loaf. By pressure, the surplus water is removed and the clay, now in flat slabs, is rolled up and passed on to the "pug mill." This piece of machinery may be likened to the domestic mincer or meat grinder. Blades, revolving in a manner popularly known as the "spiral," knead the clay and force it through a circular opening, from which it emerges as a huge "sausage." In the pottery industry, as in all other artistic crafts, mechanical means cannot effectively replace the dexterity of man or woman. The "pug mill," e.g., is an admirable method for kneading the clay, but it cannot do it so effectively as an experienced pottery worker. Such a man would cut a lump of clay into two pieces and bang one on to the other, a process which he repeats many times. Obviously this is a slower and more expensive method, and cannot be used for the cheaper types of ware.

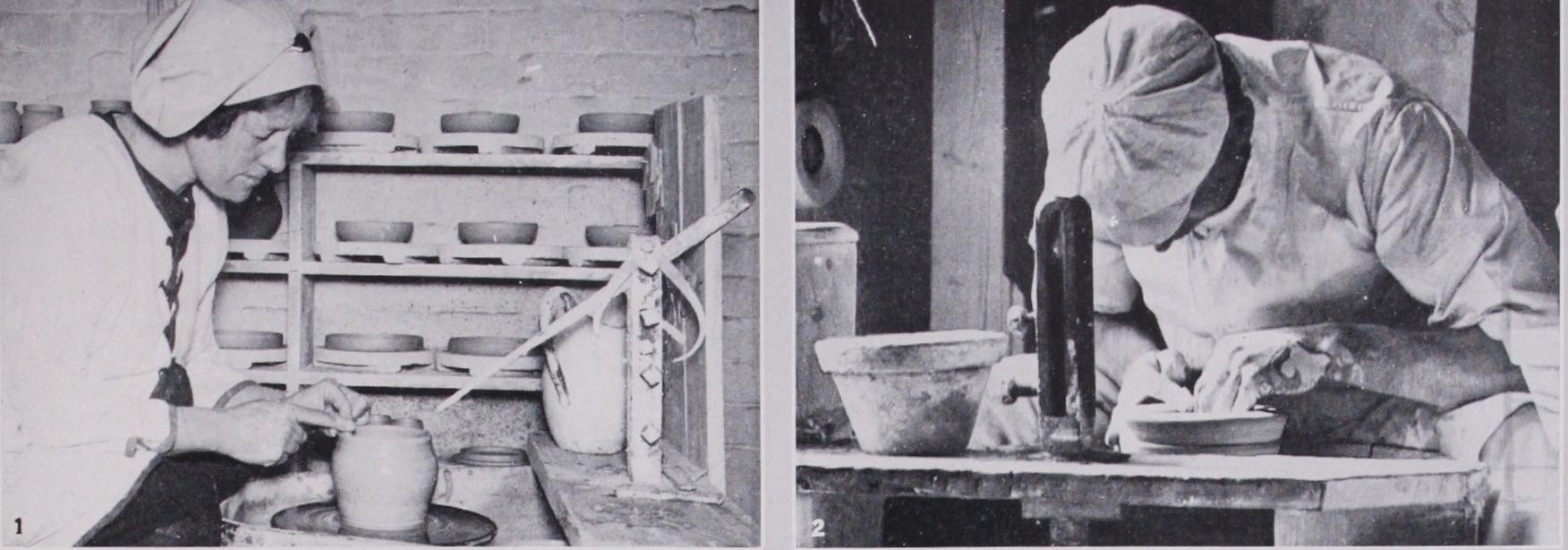

Throwing.

The clay is now ready for making into the ware. Everyone has heard of the potter's wheel, but many have prob ably not seen one or have an incorrect impression of this simple appliance, which plays such an important part in the making of some delightful pieces of pottery. It is not a wheel, as generally understood, but a circular, horizontal disc, which revolves at the will of the thrower. A ball of clay is thrown on to the "wheel," and then the "thrower," after getting it into the condition of plas ticity he considers most correct, deftly transforms the ball of clay into whatever shape he is proposing to make, by pressing it with his fingers as the "wheel" revolves. In this way a symmetri cal form is obtained. The art of the potter is infinite, and it is little wonder that his skill in transforming an ugly ball of clay into a bowl or vase of beautiful contour has moved poets to acclaim his craft.For domestic articles, such as cups, the thrower may be aided by a mould, which is made of plaster of paris. The inside of the mould will correspond to the shape of the outside of the cup. It is a simple matter—to the experienced thrower—to press the clay into the mould until the desired thickness is obtained. The plaster of paris absorbs some of the moisture in the clay, which, besides contracting, becomes correspondingly harder, and therefore much more easily handled by the potter. The cup is then passed on to a man who turns (or trims) it on a lathe. The cup, of course, is not complete without a handle, which could not be thrown on the wheel. It is therefore "cast," the clay taking the shape of a plaster of paris mould. After trimming, the handle is affixed to the cup by dipping the ends in some "slip." When joining together two pieces of clay, it is important to ensure, as far as possible, that the percentage of moisture is approximately the same in each, for if one is drier than the other, unequal contraction will take place, with the result that the two will part company. This is one of the many contingencies that the potter has to guard against, and it will readily be seen that a large amount of skill and experience is necessary for the production of good pottery.

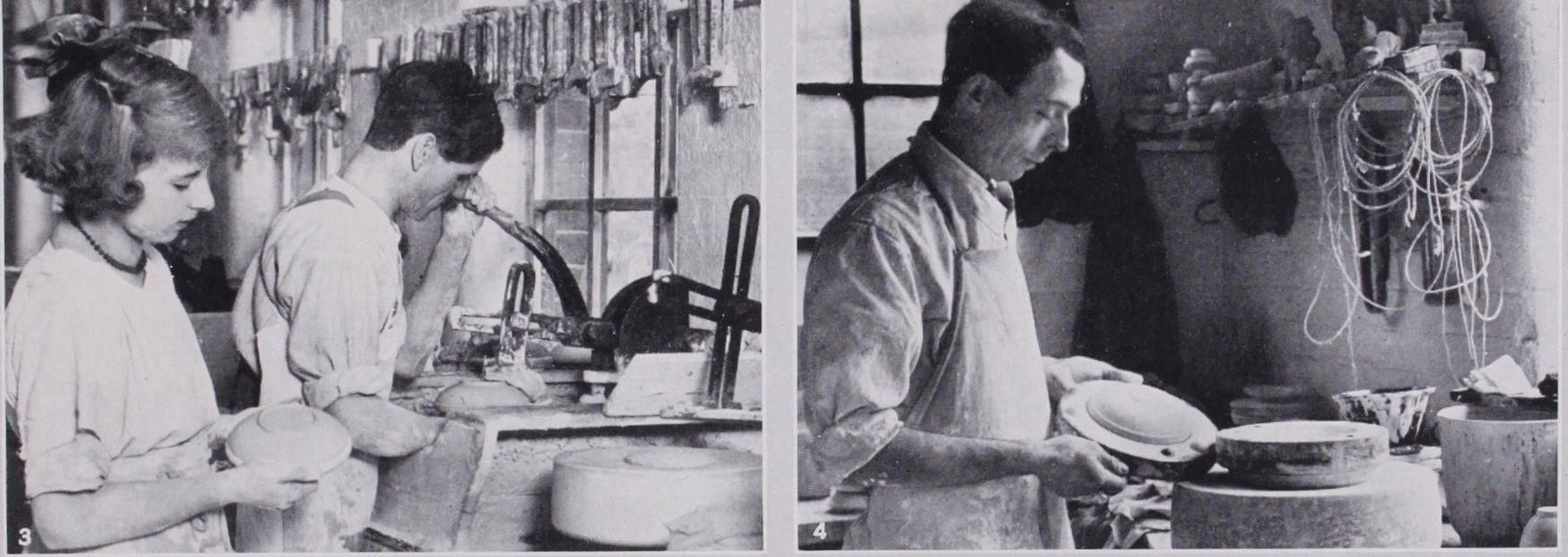

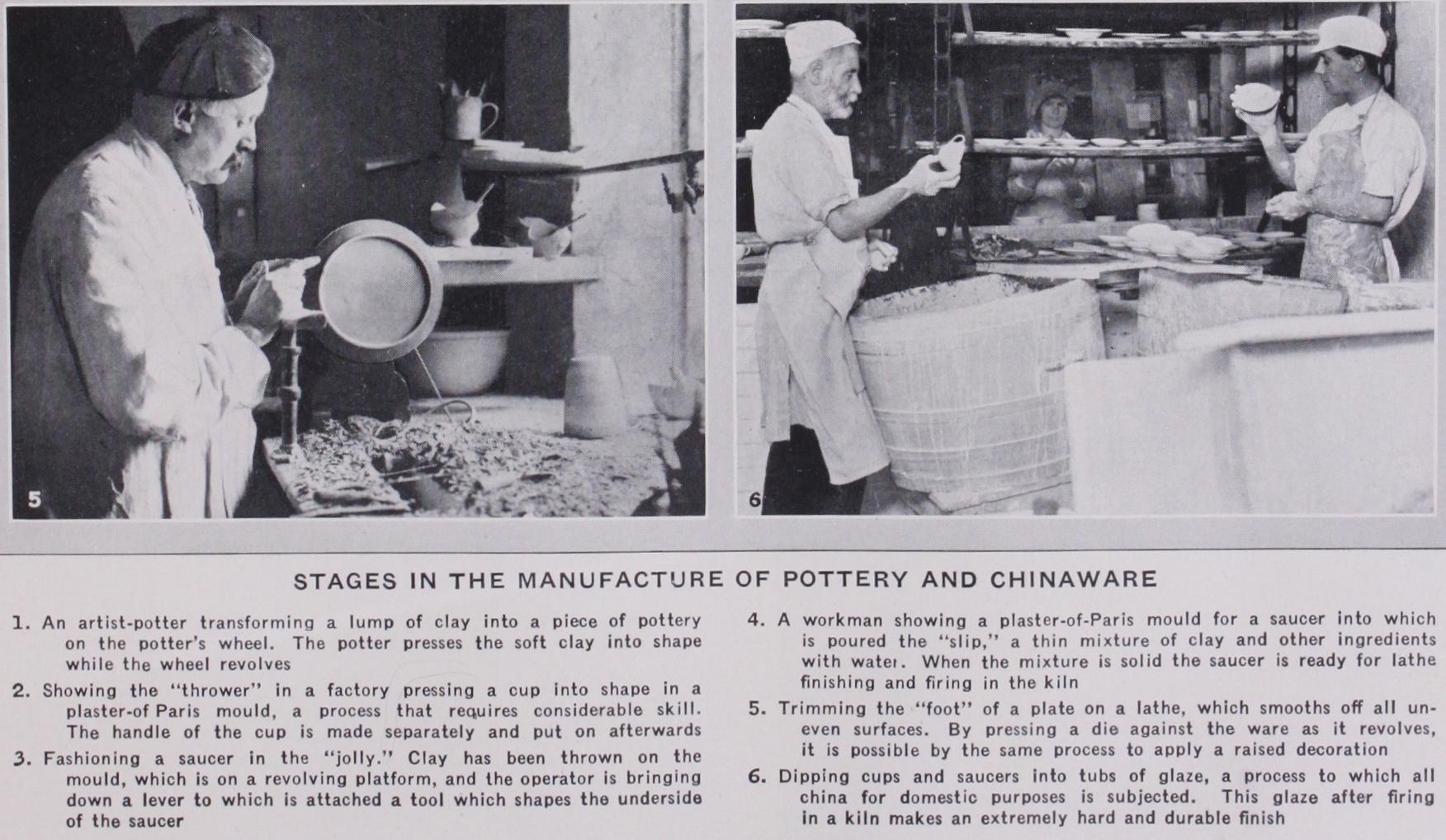

Turning.

This important operation in the manufacture of pottery has been mentioned above. It will be obvious that the products from the thrower's hands will need trimming if a smooth finish is required. Some potters, particularly those known as "artist potters," who, however, usually work with coarser "bodies" (heavier types of clay), like to leave the marks of the thrower's hands, just as some take a pride in the hammer marks on hand wrought silver ware. In commercial production, particularly if moulds are used, as mentioned in the previous paragraph, a little trimming is necessary. When the ware is moulded, a process that will be described later, turning will be an essential operation.It must be remembered that the clay, when it reaches the lathe, is becoming harder; at this stage it is known as "green hard," a condition which has been likened to hard cheese, while another description is "leather hard." In such a condition the cup or other article can be shaved or trimmed on a lathe just as a piece of wood can. Any unevenness can be removed, while, if a "foot" for the ware is required, this can be formed by the turner. An additional advantage of the lathe is the speed with which the ware may be "embossed" with decorations, such as beads, etc. While the ware revolves, the turner presses against it a little wheel, which has the decoration engraved upon it, in reverse.

The lathe used for this work resembles in many respects the machine used for wood or metal turning. The principal difference is the method of holding the article to be turned. In the pottery industry, the ware is placed in a "chum," a hollow drum that grips the piece at about half its length. When the exposed half has been finished, the ware is reversed and the process continued.

In the case of cups, and other ware requiring handles, it will be obvious that the turning must be done before the handle is applied.

Jolleying.

Although the methods of the early potter have remained almost unaltered in many respects, the large output of the modern factories makes it necessary to provide a means where by a more rapid production of ware can be maintained. The "jolley" takes the place, to some extent, of the thrower ; but man's skill is still needed to ensure the output of good pottery. Again, we have a small revolving disk, and on this a mould of the exterior of the article to be made is placed. Into this a slab or "bat" of clay is thrown. The mould forms one side of the piece of ware (the exterior), and the interior is shaped by a "profile" which is brought down by a lever and cuts away the clay to the desired thickness, the mould on the platform being revolved during the process.For flat ware, such as plates and saucers, the procedure is slightly different. Such pieces are made upside down, the bottom of the plate, or saucer, being uppermost. The mould in this case will furnish the shape of the interior or top of the ware, while the profile, which is lowered on to the revolving slab of clay by the lever, will form the underside.

When the piece of ware has been fashioned on this machine, it is taken, still on the mould, to a drying chamber. Here the clay contracts and the saucer, or whatever it may be, is lifted away and passed on for finishing. This means the trimming of the edges, and smoothing with a flannel and fine sandpaper. It it should be a cup, a handle has, of course, to be applied.

Pressing.

This process consists of placing soft clay, which has been beaten out to the required thickness, into plaster of paris moulds, which may form one half of the ware. When the halves have been made they are brought together to form the whole, the joints being finished off. After sufficient water has evaporated, the ware can be removed, and handles, knobs, feet, or any other parts which have been fashioned in a like manner, are then attached.

Casting.

Many will have a passing acquaintance with this process, for the method of casting metals is well known ; in the pottery industry the "slip" takes the place of the molten metal. The "slip" is poured into plaster of paris moulds, which absorb some of the moisture, leaving a layer of clay. When the clay is of sufficient thickness, the surplus "slip" is poured away, and the mould, with its clay lining, is taken to the drying room, where the ware contracts and hardens, making it suitable for removing and finishing off as in the case of pressed ware. The moulds may form only part of the finished article, the remainder being made in other moulds. When ready, the pieces from each mould are joined together. It will be seen that casting is similar to pressing, except that the potter is able to commence with an easily handled ma terial (the "slip") which, owing to its limpidness or low viscosity, rapidly takes the shape of the mould. The process is therefore simpler and, consequently, cheaper. It is a method which lends itself admirably to the reproduction of figures and other modelled ware.

Mould-Making.

Plaster of paris moulds have been fre quently mentioned in the various processes already described, and it will be useful to interpose here a brief description of the mak ing of these moulds, as, undoubtedly, it is an important feature in modern pottery manufacture.Plaster of paris is made from gypsum, a naturally occurring mineral composed of calcium sulphate. Gypsum is hydrated, i.e., it contains a certain amount of combined water, which can be driven off by heat. When it has been calcined an amorphous pow der is left, known as partially hydrated calcium sulphate, or plaster of paris.

This material has a peculiar property in that it swells when water is added, forming an absorbent solid, which lends itself readily to the formation of various shapes by carving, turning on the lathe, etc. Every cup, jug, or other piece of ware produced, must, of course, have had an original from which it is duplicated. The original is modelled in clay and is solid, i.e., it gives the shape of the exterior only. From this model the plastor of Paris mould is prepared. This is a process that needs special care, for upon the mould the accuracy of all the reproductions depends. The mould may be in three parts, two halves, forming the sides, and a bottom. From this mould a duplicate of the original can be produced, and, in turn, moulds for reproductions. The number of pieces of a mould will depend upon the shape of the article to be made.

Modelling.—As stated above, every piece of ware produced must have had an original, which may vary from an ordinary tea pot to a dainty shepherdess, or a group of several figures. The modeller's skill in this matter may be likened to that of the artist who paints a picture for reproduction. The modeller creates and the craftsman copies.

But the task is not ended when the modeller has finished his work; considerable skill is required to reproduce his work faith fully. When the modeller's work takes the shape of a figure in fanciful pose, many moulds have to be made, and the number may be as high as 28. Arms, legs, hands, head and many other parts have to be moulded separately and then joined to make the figure created by the modeller. As the pieces are often hollow, it will readily be seen that great care must be exercised by the man whose occupation it is to assemble the various parts, as undue pressure on the pieces would cause distortion and the spirit of the model ler's art would be lost.

A further difficulty, which affects the modeller, is that allowance must be made for contraction. The mould from his model will, of course, give a piece of ware corresponding, in its raw state, to the original; but when the reproduction has lost its moisture and has been further contracted by the firing, the figure (or whatever it may be) will be much smaller. This shrinkage may be as much as one-tenth. Obviously the modeller must keep this in mind when at work on an original.

Firing.—The processes described have led up to the first firing of the ware, when what is known as "biscuit" is produced.

The shape of a pottery oven, or kiln, will be familiar, by photo graphs and drawings, to many. The huge, bottle-shaped ovens are peculiar to the pottery industry. They are heated by fires placed at intervals at the base. Coal is the fuel principally em ployed, but electrically heated ovens have made an appearance, while oil and gas have their advocates. On the Continent and in the Far East wood often plays an important part in the firing.

As thousands of pieces of ware may be fired at one time, the arrangement in the oven needs special care. It would not, of course, be possible just to stack clay cups on top of one another; even if they kept in position, the weight on those below would, at least, cause distortion. The ware is therefore placed in "sag gars," which are largely fireclay receptacles resembling big cheeses in shape. In these the "green" ware is placed, separated by ground flint, which, owing to its very high melting, or fusing point, will not affect the ware in the oven. The "saggars," when filled, are "placed" in the ovens, special care being taken to see that they are perfectly level. As a rule, hollow ware (such as cups) is placed at the top of the oven and flat ware (such as plates) at the bottom. When filled, the ovens are sealed up and the heating is commenced, continuing for about 5o to 6o hours. For the first 24 hours the firing is slow, i.e., the temperature is not raised un duly, to drive out the moisture. The temperature will then be increased until it reaches about 1,300° C. A necessary precaution is to ensure that the temperature never falls back. This is part of the fireman's responsibility; he must also know when the firing is complete. He has means of testing the rate of progress of the firing, but the control of the temperature and the length of time given needs skilful judgment. Very useful pyroscopes for determining the proper heat treatment attained in an oven are employed frequently. Some are small tetrahedra, called cones, compounded from a series of ceramic mixtures. These cones are placed in the oven where they may be observed by the fireman. As a certain temperature is reached, depending somewhat on the rate of temperature increase, they bend so that the apex gradually touches the base. The finishing point of the firing may thus be indicated. These pyroscopes are called Seger cones after their inventor. Other temperature indicators are Holdcrof is thermo scopes. These are small bars supported at their ends in a hori zontal position. When the critical temperature of a bar is reached it sags in the middle. The Seger cones and Holdcrof is thermo scopes are given a variety of numbers, the refractoriness of the cone or bar increasing as the numbers go up. Pyrometers, scientific instruments for measuring heat, may be employed instead of the pyroscopes. When the firing is complete the oven is allowed to cool; this takes about the same time as the firing-5o to 6o hours.

The biscuit ware, when it leaves the oven, must be translucent, and it is the aim of all the makers to obtain a ware with a perfect translucent body, free from blemishes.

Glazing.—When the "biscuit" ware produced by the first fir ing has been sorted (for the rejection of any pieces containing flaws), and cleaned, it is ready for the "dipper," the man who dips the piece into a tub of glaze. The glaze is made from a va riety of ingredients which, when fused, form what might be termed "glass," for the glaze on a piece of china is really a glass. Lead is an important ingredient in many glazes and the question of lead poisoning has long been a problem in the pottery industry ; but this is being overcome by the introduction of low-solubility glazes.

It may appear a simple matter to dip a cup into a tub of glaze, but here, as in most of the processes through which the ware has to pass, the skill of the worker is all important.

The ware, with its coating of glaze, has now to be fired again, when the opaque covering will be rendered translucent. The china is arranged in saggars, the round, cheese-shaped, fireclay recep tacles already mentioned, but this time the saggar will be glazed inside, otherwise trouble would arise owing to absorption. The saggars are "placed" or stacked in the oven. This oven is known as the "glost" oven, and the man who stacks the saggars contain ing the glazed ware is called a "glost placer." Before the ware reaches the "glost placer" it passes through a drying room and is cleaned. Where there are small holes in the ware, in pepper pots, for instance, any glaze filling the openings must be entirely removed.

The saggars are arranged in the oven, as in the case of biscuit ware, but this time rolls of fireclay are placed between the saggars. This clay, by the pressure of the saggar above, effectively pre vents any products of combustion from reaching the glaze, which, obviously, would be spoiled.

Decorating.

In the early days of pottery making, decoration was not as we understand it to-day—it was confined more to shapes than applied colours. Those who are familiar with the Greek urns will readily appreciate the beauty of the outlines ; but in the loth century pottery is judged more by the decorative scheme. Our modern potters do, of course, pay considerable atten tion to shapes ; but the general public, with an appetite for colour, looks for applied decoration.The limitations, and the great skill required by the pottery artist, are little known to the average purchaser in a retail estab lishment. Unlike most other decorative processes, the colours, especially if under the glaze, have to be subjected to a very high temperature for the glaze itself demands this, and therefore many pigments are unsuitable, as they would be destroyed by the heat. Metallic oxides are used, such as cobalt oxide for blue, uranium oxide for yellow, chromium oxide for green, iron oxides for reds and reddish browns.

Underglaze decoration is particularly suitable for household ware, as it is indestructible, and cannot be worn off in use. On the commoner types of domestic china the design would probably be "printed," a process which is carried out as follows. A copper plate is engraved with the design, which is filled with colour mixed with oil. The printer cleans off any surplus colour and then applies a sheet of tissue paper (which has been water sized) to the plate. The copper plate, with the paper above, is then passed through a roller press, which causes the decoration to adhere to the paper. The tissue is now pressed on to the ware, and on its removal, by soaking in water, the decoration remains behind. The design will probably be in outline and this may be filled in by hand, an oper ation cleverly carried out by girls. When the decoration is com plete the next step is to remove the oil, for this would interfere with the application of the glaze. To do this the ware is placed in a kiln, where it is fired at a low temperature, though a suffi ciently high one to destroy the oil and leave the colour "fixed." The china is now ready for the glaze, and is finished as already de scribed. work can also be done under the glaze— with a limited palette.

For overglaze decoration a much wider range of colours is possible. A flux is added so that the resulting colours are really glasses, although enamels, as they are called in the industry, is a better term, which will be readily understood if one thinks of the enamelled ware in jewellers' shops—not the air-dried enamel used by house decorators.

Many pieces of domestic ware have a gold band or a gold treat ment somewhere in the decoration. This is applied in two forms : "best" gold and "liquid" gold, which is an alloy. The "best" gold comes out of the kiln in a dull condition, but can be burnished to a bright tone. The "liquid" is bright when it leaves the kiln, but it has not the beauty or the wearing qualities of the other. There is a type of decoration known as "acid gold." A design is etched on to the glaze with hydrofluoric acid, which eats away the glaze unprotected by a "resist." The etched part may be coated with "best" gold, which, after being fired, is burnished, with the result that the gold in the depressions formed by the etching re mains dull, while the burnished part is bright.

The decoration particularly suitable for rapid production is that of lithography. Lithographed designs are quite common for the cheaper classes of ware, and, while they may not always appeal to the critical eye, nevertheless satisfy a large percentage of the population.

The design is made up on several stones, one for each colour. These colours are transferred to sheets of paper, so that the com plete decoration is obtained on one sheet. We have now what is commonly termed a "transfer." This is applied to the ware, the design remaining after the removal of the paper. The col ours are fired in the enamel kiln.

A type of decoration that has not been employed to any great extent since the 1 gth century is that obtained by building up flowers, in clay, petal by petal, on the ware. This calls for exceptional skill on the part of the artist.

Very fine effects are obtained with a process of decoration known as "pate-sur-pate." Commercially various designs are modelled in white clay and affixed to the ware.