Sea Defence Works

SEA DEFENCE WORKS The most important forms of sea defence works in common use in Holland are : (a) groynes, (b) sea walls or "dikes" and (c) fascine mattresses with stone ballasting for the protection of submerged banks.

Groynes.

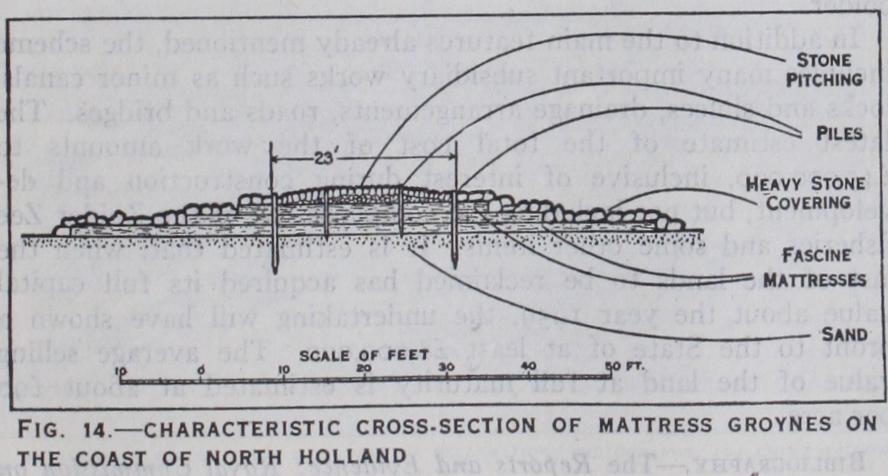

Groynes are usually constructed at right angles to the shore line and are maintained as a rule at a small height above the average foreshore level. On those portions of the North sea coast which are most exposed, groynes are placed about 25o metres apart and are extended out beyond the low-water line. Many of the groynes on the Dutch coast are constructed of layers of fascine mattresses covered by heavy stone, having their crests almost flat or turtle-backed with side slopes of i in 2, or flatter. The fascine or brushwood mattresses are held together and pinned down by rows of piles. Wide brushwood aprons, with heavy stone covering forming flat slopes, are constructed on either side of the groyne in order to protect the flanks against scour (fig. 14). The groynes are carried up above the line of high water to meet the base of the sand dunes or the protecting dikes. These groynes, inclusive of the side aprons, are often of considerable width, sometimes as much as 3o metres at their deepest and widest parts. The cost of groynes recently built in Holland has varied from £4,000 to £ i i,000 each.

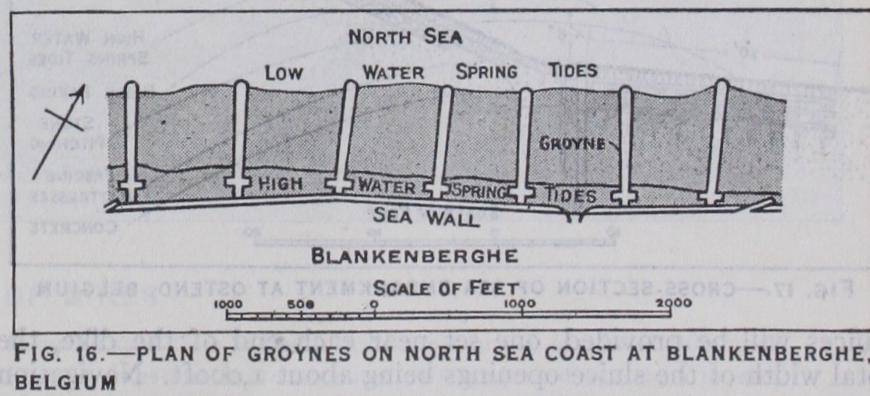

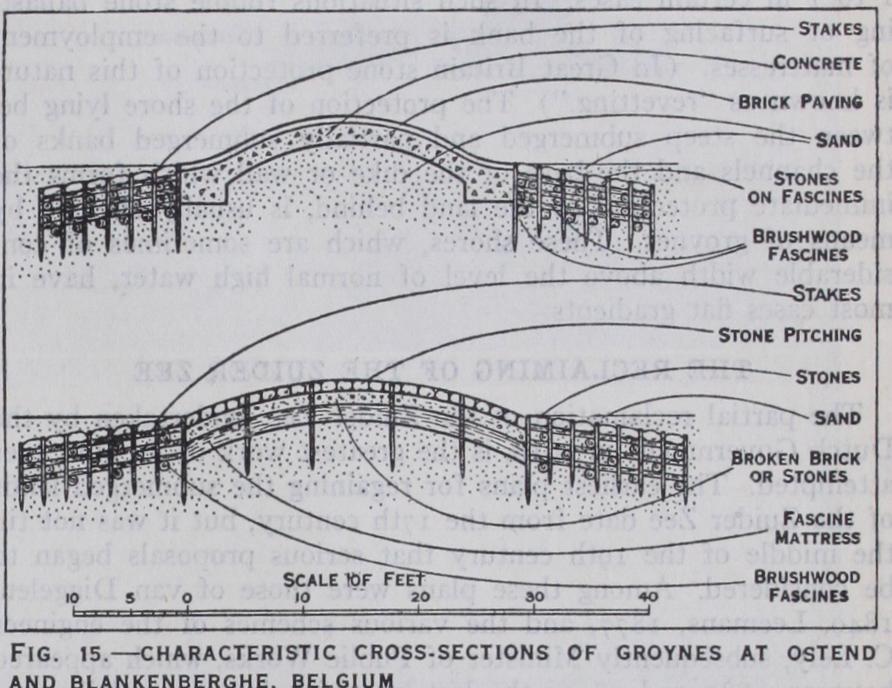

On the coast of Belgium at Blankenberghe and in its vicinity the shore is groyned on an extensive scale. The groynes on the average are about 82oft. long and 68oft. apart ; they resemble the typical Dutch groyne in form and are constructed with a foundation of mattress work or concrete, faced with brickwork or stone pitching (figs. 15 and 16) .

Dikes.—On much of the North sea coast-line of Holland and Belgium, where the beach is protected from erosion by groynes, the sand dunes or the coastal embankments (dikes) are frequently protected by a flat slope of brickwork, or basalt or other stone pitching, or concrete slabs laid on beds of clay, rubble and mattress work (fig. 2) . In situations, such as Scheveningen and Ostend, where a promenade has been formed on the sea embank ment, a curved faced wall is sometimes substituted for the upper part of the normal slope of the paving thus reducing the width of the protecting works (figs. 17 and 18) ; but over large stretches of coast, particularly in Holland, a simple flat paved slope is the common practice.

Protection of Submerged Banks.

The underwater banks of some of the estuary channels and sea inlets on the Dutch coast often stand at a steep slope with deep water alongside. Under these conditions there is serious liability to erosion and it is usual to protect the banks both above and below water by artificial means. For many years fascine mattresses have been used for this purpose. These are made up on a convenient sandy foreshore, covered at high tide, and, when completed, are towed to the place where they are to be used and sunk on the sea bottom by ballasting with stone. They consist of two layers or grids of brushwood each built up of crossed rows of parallel brushwood ropes, 0.4 metre circumference, and spaced 0•9 metre apart centre to centre, bound tightly together with a filling of brushwood in three layers between them. On the top of the upper brushwood grid, openwork par titions are formed for the reception of stone ballast. Formerly, clay mixed with a little stone was used for ballasting, but in mod ern practice stone alone is employed, the mattresses being weighted to the extent of i,000kg. per sq. metre. The cost of continuous protection of the steep banks of the estuary channels, where the depth of water alongside is sometimes as much as looft., is very considerable, amounting in some cases to as much as f I oo per metre run of bank. In some localities the cost has been reduced by the construction of intermittent mattress work, leaving short unprotected stretches of bank between projecting spurs which serve to deflect the main current away from the unprotected embayments. In cases where the sea bed of the deep channels consists of clay, erosion is not so uniform as that of sandy bottoms and the side slope is sometimes very steep, exceeding I to I in certain cases. In such situations rubble stone ballast ing or surfacing of the bank is preferred to the employment of mattresses. (In Great Britain stone protection of this nature is known as "revetting.") The protection of the shore lying be tween the steep submerged and partially submerged banks of the channels and the base of the dike or wall which forms the immediate protection of the land behind, is usually effected by means of groynes. These shores, which are sometimes of con siderable width above the level of normal high water, have in most cases flat gradients.