Sition and Varieties Chemical and Physical Characteristics

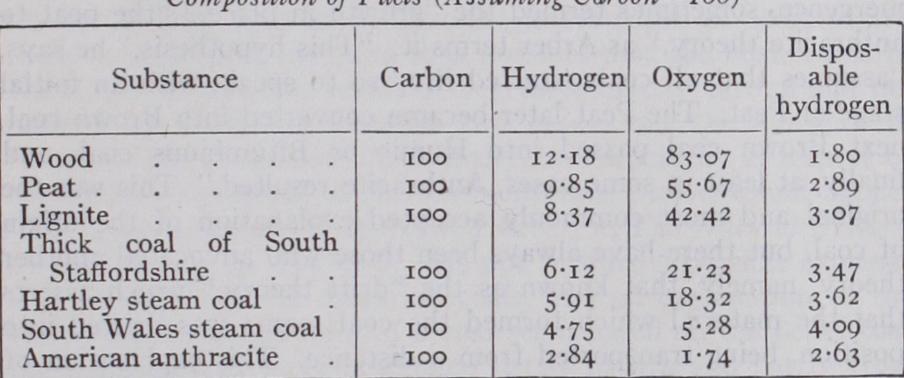

SITION AND VARIETIES; CHEMICAL AND PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS Coal is the outcome of a process of transformation whereby the oxygen and hydrogen contained in the woody fibre and other vegetable matter are eliminated in proportionally larger quantity than carbon, so that the percentage of the latter element is in creased. This is excellently demonstrated in the following table prepared by the late Dr. Percy. The mineral matter is also changed by the removal of the silica and alkalis and the substi tution of substances analogous in composition to fireclay.

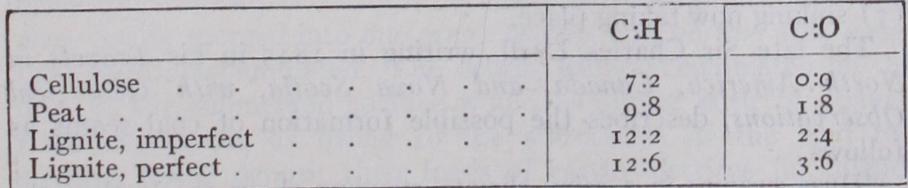

The causes and methods of these changes are not yet fully understood ; indeed, perhaps of all the problems connected with the natural history of coal we know least about the means of its conversion, although the researches of B. Renault ("Sur quelques Micro-organismes des combustibles fossiles," Bull. Soc. Indust. Miner., Ser. 3, vol. xiii., p. 868, 1899; vol. xiv. p. 5, 1900, and "Recherches sur les Bacteriacees fossiles," Ann. Sci. Nat., Ser. 8, Bot. vol. ii. p. 275, 1896) have gone a long way towards helping us to an understanding of the processes involved in the trans formation of the original vegetable matter into coal. The product coal is evidently the result of biochemical action, the agents of the transformation of the cellulose into peaty substance being saprophytic fungi and bacterial ferments. The ultimate term of bacterial activity seems to be the production of ulmic acid, con taining carbon 65.31% and hydrogen 3.85%, which is a powerful antiseptic. By the progressive elimination of oxygen and hydro gen, partly as water and partly as carbon dioxide and marsh gas, the ratios of carbon to oxygen and hydrogen in the reduced prod uct increase according to the age of the formation in the following manner :— The resultant product of the action of the bacteria and fungi is a brown pasty or gelatinous substance which binds the more by bacteria. The brown or black opaque ground substance of the coal is to be accounted for as the final product of the destruction of the tissues by the bacteria.

Laboratory research has shown that the alkalinity of a medium can be maintained for a considerable length of time by the hydrol ysis of sodium-clay, and that a roof containing hydrolysing sodium-clay is impermeable to gases and water; that the condi tions under such a roof are what is termed anaerobic (non aerated), and that the alkaline medium produced under such a roof is suitable for continuous decomposition of organic matter. An examination of roofs of coal seams has shown that they are alkaline and contain sodium-clay. Mature leaves have been sub mitted to bacterial decomposition under a sodium-clay roof, with the result that the residual solid product was black and possessed the typical fusain structure. (E. Mackenzie Taylor, "Base Ex change and the Formation of Coal," Nature, vol. cxx., pp. 448, 449, The actual conversion of this product into coal, it is supposed, is due to what is termed regional metamorphism. The mass of decomposed vegetable matter being over-laid by the deposition of layers of sand and mud due to the sinking of the land, it is sub jected to an ever increasing weight of superincumbent strata compressing it into a much smaller compass and profoundly affecting it in other ways. We know, also, that towards the close of Palaeozoic times the regions occupied by the British coalfields were subjected to great earth movements due to volcanic dis turbance, to such an extent that the horizontal deposits—coals, sandstone and shale—became tilted, faulted, folded or contorted. The sandstones and shales, being hard rocks, were not altered structurally to any great extent, but the comparatively soft altered vegetable layers, as the result of the pressure and the heat caused by the pressure, would undergo great physical and chemical changes. The changes due to these geological causes have been rapidly accomplished, as pebbles of completely formed coal are found sometimes in the sandstones and coarser sedimentary strata alternating with the coal seams in many coalfields.

Different views have, from time to time, been held as to the nature and growth of the plant life which constitutes the mother substance of the coal seams. In 187o, Huxley, in an article in the Contemporary Review, described the "Better Bed" coal seam of Bradford, Yorkshire, as being composed chiefly of and spores, but as Prof. W. C. Williamson of Manchester after•• wards showed him, the sporangia were really megaspores of crypto gamic plants. Megaspores (female spores) and microspores (male spores) are very largely in evidence in British and many other coals, whereas in some others no trace of spores can be found. Woody matter must have entered very largely into the composi tion of the original vegetable mass of some coals, as for instance the coalfield of St. Gtienne in Central France, where, as M.

Grand' Eury has shown, some of the coals are homogeneous deposits composed of the bark of Cordaites, or of species of Calamites. Dr. Marie Stopes has shown the same to be true of many British coals. According to Goeppert, seams of coal in Upper Silesia appear to be largely, if not entirely, composed of Sigillarian wood, impressions of the bark of this plant, and some times impressions of the leaves, being recognized between the layers of coal.

It is clear, therefore, that coal is made up of many constituents : (a) woody or xyloid substances, which are so characteristic of lignite coal, called by some "anthraxylon" (from anthrax, coal, and xylon, wood) ; (b) canneloid material, consisting largely of spores of cryptogamic plants, of which cannel coal is chiefly composed; (c) resinous matter, occurring largely in lignites but rarely in cannels ; (d) macerated material mixed with woody matter and best described as debris, as it contains all the pre viously mentioned substances; (e) the "fundamental matter" of White and Thiessen, which is the colloidal ground mass in which the other constituents are embedded, and which is composed chiefly of the more readily decomposable parts of the vegetable matter. The vegetable constituents of coal are, therefore, cellulosic and resinous.

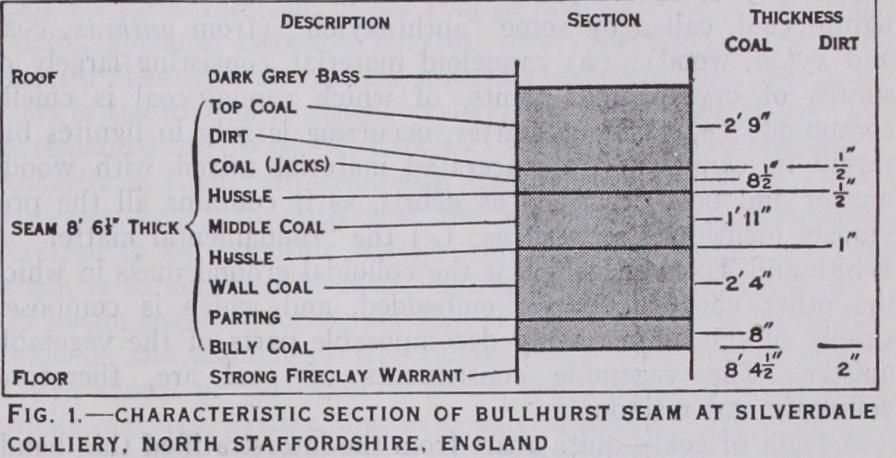

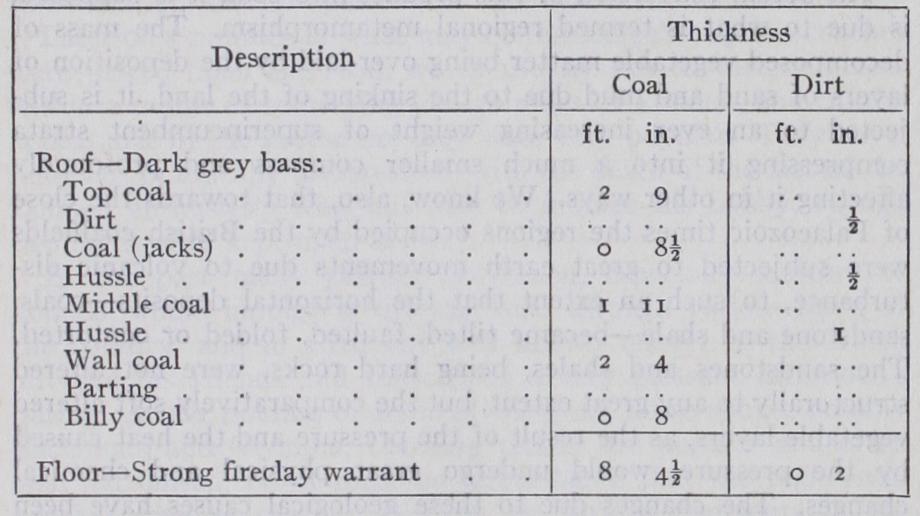

A seam of coal—quite apart from the interstratified thin bands of argillaceous or more rarely of arenaceous matter (which occur in the case of many coal seams—layers variously termed bands of "dirt," "clod," "clift," "hussle," or "stone")—consists of layers of different classes of coal, a seam seldom being homogeneous in point of chemical composition or physical character throughout. But even where the seam comprises but one class of coal, as has been long known, it is made up of laminae of "bright coal" (the Glanz Kohle of Germany) and "dull coal" (Matt Kohle), the laminae being divided by an amorphous powdery substance known as "mineral charcoal." Of late years, and for no very obvious reason, it has become customary to designate these varieties by the French words "vitrain" and "clarain" for the bright coal, "durain" for the dull coal, and "fusain" for the mineral charcoal. The exact origin of these substances, which vary in composition, is not quite clear. Thus the following is a typical section of the Bullhurst seam of coal at the Silverdale colliery in North Staffordshire (see fig. 1) :— In this seam several classes of coal are divided from each other by thin strata of argillaceous (shaly) matter, the coal itself being composed of bright and dull coal with interposed bands of mineral charcoal.

The Formation of Coal Seams and Variation in the Character of Coal.—It might naturally be supposed that if the origin of the coal seams was the same in each case, that is to say, if they were the result of the submergence of forests of cryptogamic and cotyledonous plants, in point of chemical com position there would be no, or at any rate almost imperceptible, variation ; but such is not the case. Not only is there variation in composition as between different coal seams, but the same seam in a given coalfield in some cases—notably in South Wales— shows considerable variation in different areas.

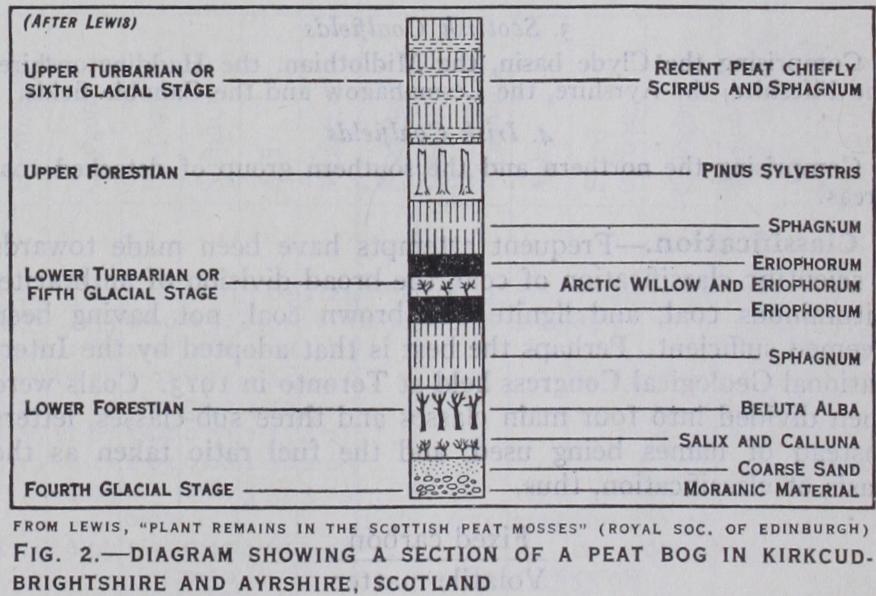

A given seam may—frequently does—vary in character verti cally and laterally. The reason for the variation in the character of the coal in the different horizons of a given seam, and in the genus of the plant remains, may probably be explained to some extent by what is to be observed in some peat bogs (F. J. Lewis, "The Plant Remains in the Scottish Peat Mosses," Trans. Roy. Soc. Edinburgh, vols. xli.; xlv.; xlvi.; 1906, 1907), where the sequence can be diagrammatically represented in the following manner (see fig. 2) :— With regard to lateral variation, in some cases, undoubtedly, the change is properly attributable to metamorphism consequent upon igneous intrusion, earth movements, and other kinds of geo thermic action, causing greater or less loss of volatile constit uents during, or it may be subsequent to, the period of coal transformation, conditioned by differences of permeability in the enclosing rocks, which is greater for sandstones than for argilla ceous strata; but these agencies would not meet the whole prob lem and none of them appears to be applicable over more than comparatively limited areas. In the investigation of this problem of difference, we are inevitably forced to consider the question of the mode of formation of coal seams.

There are in this connection two schools of thought, that which advocates the terrestrial theory, that is, the accumulation of the vegetable matter on dry or marshy land and its subsequent sub mergence, sometimes termed the "growth in place," "the peat to anthracite theory," as Arber terms it. "This hypothesis," he says, "assumes that all coals `started life,' so to speak, with an initial stage of Peat. The Peat later became converted into Brown coal, next Brown coal passed into Humic or Bituminous coal, and finally, at least in some cases, Anthracite resulted." This was the original and most commonly accepted explanation of the origin of coal, but there have always been those who advocated another theory, namely, that known as the "drift theory," which asserts that the material which formed the coal seams was drifted into position, being transported from a distance. This explanation of the mode of formation of coal seams was advocated by H. Link as far back as 1838.

The advocates of the in situ theory point to the Great Dismal Swamp of North Carolina and Virginia and to the great peat beds of Northern Europe. The Dismal Swamp is a fresh-water swamp of peat and forest, the area of the inundated portion of which is about 38 m. north and south by 25 m. east and west (N.S. Shaler, "Geology of the Dismal Swamp District of Virginia and North Carolina," U.S. Geol. Survey, Tenth Ann. Rept., pt. 1, pp. 1888-89), and was extending its borders before drainage and cultivation by man began. Osborne estimates that the original area of the Swamp was 2,200 sq.m., of which 700 have now been drained. (C. C. Osborne, "Peat in the Dismal Swamp, Virginia and North Carolina," U.S. Geol. Survey, Bull., 711-C. 1919.) Shaler outlines the series of geological events in connection with this swamp as follows : (1) a subsidence causing the formation of the Pliocene plateau, (2) elevation permitting of erosion of the Plateau, (3) subsidence permitting of the deposition of non fossiliferous sands, (4) elevation permitting carving of the sur face, (5) subsidence and the formation of the nausemond escarp ment, (6) re-elevation and development of valleys and streams, (7) sinking now taking place.

The late Sir Charles Lyell, writing in 1845 in his Travels in North America, Canada, and Nova Scotia, with Geological Observations, describes the possible formation of coal seams as follows : "Huge swamps in a rainy climate, standing above the level of the surrounding firm land, and supporting a dense forest, may have spread far and wide, invading the plains, like some European peat-mosses when they burst ; and the frequent submergence of these masses of vegetable matter beneath seas or estuaries, as often as the land sunk down during subterranean movements, may have given rise to the deposition of strata of mud, sand or limestone immediately upon the vegetable matter. The conversion of successive surfaces into dry land, where other swamps supporting trees may have formed, might give origin to a continued series of coal measures of great thickness." A possible explanation of the variation in quality of the coal in the same seam is afforded by Lemiere in the Bulletin de la Societe de l'Industrie Minerale, Ser. 4, vol. iv., pp. 85i and 1299, vol. v., p. where he maintains that the differences in composition are mainly original, the denser and more anthracitic varieties repre senting plant substance which has been more completely macer ated and deprived of its putrescible constituents before sub mergence, or of which the deposition had taken place in shallow water more readily accessible to atmospheric oxidizing influences than the deeper areas where conditions favourable to the elabora tion of compounds richer in hydrogen prevailed.

On the other hand the advocates of the drift theory say, (1) seeing that the great mass of the rocks forming the coal measure series are formed of water-borne and water-deposited material, it is only reasonable to suppose that coal was likewise so borne and deposited; (2) that the areas occupied by the coal-bearing rocks are too extensive to have originated under estuarine condi tions such as exist today; (3) that coal is usually a stratified rock, and so it would be were it derived from drifted material; and (4) that the splitting up of seams is difficult to account for under the in situ theory, but is explainable under the drift theory. These are, perhaps, the chief arguments advanced against the growth in situ theory. Probably both theories are applicable; some coalfields being formed in situ, others being the result of water-borne and water-deposited vegetable matter. Certainly the carbonaceous material in the small coalfields in south-western France, deposited in basins formed in the metamorphic rocks and resting directly thereon without the intervention of sedimentary rocks was water-borne ; and It is possible that the coal seams in Natal are likewise the result of vegetable matter carried and de posited by water—to mention two cases; but the evidence in favour of the growth in situ of many, and especially in respect of the British, coalfields of the Carboniferous period would appear to be overwhelming. E. A. Newell Arber, in The Natural History of Coal (1911, pp. 115-118), has put forward a possible explana tion of the origin of estuarine coals, and an explanation of the varied nature of the flora of a coal seam based on the belief that the material may have originated partly in situ and partly from drifted vegetation. He points to the fact that the carboniferous period was admittedly one of "ups and downs," the surface of the land either slowly sinking or being gradually raised, there being a great number of these alternating periods; that during periods of elevation, the surface was covered with dense vegetation of varied forms, tree forms predominating. He thinks there is no reason why such typical representatives of the classes Lycopodi ales, Cordaitales and Pteridospermeae as Lepidodendron, Cor daites and Lyginodendron should have been confined to marshes, and that there were in Carboniferous times as now varied upland associations as well as hygrophytic and halophytic, lowland as semblages. During periods of elevation, there existed, as to-day, fresh-water, brackish-water, or marine conditions. When the land began to sink two changes took place : the estuaries and swamps were invaded, becoming salt and brackish instead of, as formerly, brackish and fresh water, and secondly, the swamps invaded those portions of the land which were formerly elevated ground but were now sinking. Consequently, large areas of almost level sur face sank to near sea-level, or even below, and the boundaries of the future coalfield were initiated. The extent of the existing delta and fresh-water swamps became greatly magnified, and they were finally merged into one great swamp, and on this area vege table debris accumulated. The debris, which accumulated on the floor of the submerged surface would be almost entirely derived from vegetation, as owing to the subsidence of the land the streams would deposit their loads of earthy detritus far inland, and not as formerly at their mouths, now submerged. So an accumulation of purely vegetable origin would result, just as is found to-day in the Great Dismal Swamp. This accumulation would be derived in part from the former vegetation which grew in situ and was essentially of an estuarine character, and in part from plants which still flourished on the sinking land; in addition to which the vegetation from the higher lands became involved, for the trees there could no longer flourish on invasion by the swamp.

Mineral Matter Contained in Coal Seams.

Besides the purely carbonaceous matter constituting what we understand by the term coal, there is a variable quantity of mineral matter which goes to form the ash. This foreign matter consists of silica, calcite, gypsum, ankerite, barytes, iron, iron-pyrites and phos phorus. The gypsum, calcite, ankerite and barytes occur in thin films in the divisional planes, vertical and horizontal, of the coal. It remained for Crook (T. Crook, "On the frequent occurrence of Ankerite in Coal," Mineralogical Magazine, vol. xvi., No. 75, pp• 219-223, 1912) to show that the white carbonate (commonly referred to by scientific writers on coal as calcium carbonate) which is so common in coals, and is peculiarly characteristic of the steam coals of Northumberland, is in point of fact the mineral ankerite, the amount of free calcite being comparatively small. These sheets or plates of ankerite, with which are associated calcite, barytes, pyrites, and even zinc blende and galena in very small quantities are less than a millimetre in thickness and consti tute minute mineral veins. As a rule the dominant mineral is ankerite. The pyrites also occurs in divisional planes in the coal, though in the form of marcasite (a form of iron pyrites which crystallizes in prisms and is paler than "pyrite," which crystallizes in cubes) ; it is dispersed throughout the coal substance.In small part these impurities are derived from the original vegetation itself, e.g., to some extent the sulphur and silica. Decaying vegetable matter has the property of converting the iron in its composition into iron, pyrites, but the sulphur may, in part, have an extraneous origin and be due to the infiltration of mineral solutions from overlying rocks. As Thiessen has pointed out, sulphur exists in the proteins of practically all plants and there is in addition some non-protein sulphur in the majority of plants. Moore divides the sulphur contained in coal into inorganic and organic, pointing to the fact that, as has been recognized for many years, a portion of the sulphur contained in coal must exist in some form other than mineral sulphides and sulphates, as in some coals it does not exist in such proportions as can be com bined with the elements necessary to form these mineral com pounds (E. S. Moore, Coal, pp. 33-34, 1922). The inorganic type is most common. The sulphur exists as sulphide or sulphates— chiefly the former—usually of iron, and as free sulphur, and is very detrimental to smelting and gas making.

The occurrence of phosphorus in coal may be due in part to the infiltration of water from rocks containing calcium phosphate, but some of it, at any rate, is derived from the vegetation itself, for spores are known to contain phosphorus. It occurs only in minute quantity in coal, but that quantity is very detrimental in coal or coke used for metallurgical purposes.

Hydrocarbons, such as petroleum, bitumen, paraffin, etc., are found occasionally in coal seams, but more generally in the asso ciated strata of sandstones and in the lower carboniferous lime stones.

Gases, consisting principally of methane (light carburetted hydrogen or marsh gas) are commonly present in an occluded form, sometimes existing under conditions of considerable pressure, in the coal, and constituting a most formidable danger in the mine. The subject of ash in coal is dealt with more fully in the article on COKE. (See also Section III. ) Geological Formations in Which Coal Occurs.—Although by far the greater stores of coal and those of highest quality are contained in the great Carboniferous formation, and in particular in that part known as the Coal Measure series, yet the occurrence of coal is by no means limited to the carboniferous system. Eliminating lignite, which is chiefly a formation of Tertiary age, coal deposits are found as low down in the geological scale as the Silurian system, and in rocks as late as the Cretaceous age. Thus, the little coalfield of Brora in Sutherlandshire is of lower oolitic age. In Canada the coal of the Pacific Coast is of Cretaceous age. The coalfields of Cape Colony, the Transvaal and Natal are prob ably of Triassic origin. The coalfields of Russia were considered by Sir R. Murchison to belong to the Lower Carboniferous period, but others regard them as of Old Red Sandstone age. But in Great Britain the geological divisions which in this respect chiefly demand our notice are the Coal Measures. the Millstone Grit. and the Carboniferous Limestone Series, which together consti tute the great carboniferous formation of Great Britain.

In England all the coalfields, with the exception of northern and western Northumberland, are in the Coal Measures. The British coalfields may conveniently be divided in the following manner : F I. English Coalfields The Great Northern Group.—Comprising the limestone coals, North umberland and Durham coalfield and the Cumberland field.

The North Western Group.—Comprising the Lancashire and East Cheshire field, the Coalbrookdale (or Shropshire) field, and the Forest of Wyre field.

The North Midland Group.—Comprising the Yorkshire, Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire field.

The Midland Group.—Comprising the North and South Stafford shire coalfields, the Leicestershire field, and the Warwickshire field.

The Western Group.—Comprising the Bristol and Somersetshire fields and the Forest of Dean.

2. Welsh Coalfields Comprising the South Wales field, the Denbighshire field, and the Flintshire field.

3. Scottish Coalfields Comprising the Clyde basin, the Midlothian. the Haddingtonshire, the Fifeshire, the Ayrshire, the Lesmahagow and the Canobie fields.

4. Irish Coalfields Comprising the northern and the southern group of detached coal areas.

Classification.

Frequent attempts have been made towards a scientific classification of coal. the broad division of anthracite, bituminous coal. and lignite and brown coal. not having been deemed sufficient. Perhaps the best is that adopted by the Inter national Geological Congress held at Toronto in 1913. Coals were then divided into four main classes and three sub-classes, letters instead of names being used, and the fuel ratio taken as the basis of classification. thus.The cannel coals, which yield a great quantity of gas, differ in character from ordinary bituminous coals for they are dull pitchy to dark brown in appearance, break with a conchoidal fracture, are hard and dense, and devoid of coking properties. They are sometimes called "Parrot coals" because of their quality when heated of decrepitating with a crackling sound.

Coking Coal.—Certain bituminous coals under the application of heat possess the quality of intumescing, or coking, as it is termed (see post. Section III.). What determines the coking or caking property is not fully understood. It does not depend on the relative quantities of carbon and oxygen present, though coals rich in carbon and low in oxygen (e.g., anthracite high in carbon content and low in oxygen), also coals comparatively low in carbon and high in oxygen content (lignite), do not cake. That physical conditions play some part in the coking property of coal would seem to be borne out by the fact that certain coals which do not readily coke, when ground fine enough and subjected to pressure do so. The principal requirement in respect of a house coal is that whilst it should produce a good bright fire it should not be too fierce, for which reason a steam coal and a furnace coal are not desirable. Owing to its intumescent quality a coking coal is also undesirable.

Manufacturing, Steam or Furnace Coals.—These should be capable of producing considerable heat, for which reason they should have a fairly high fixed carbon content but a low sulphur content. The most important characteristic of a steam coal is agreed to be inherent great heating power, and, whilst the fixed carbon content should be high, there should also be present a suf ficient percentage of volatile hydrocarbons to permit of easy igni tion and consumption of the fixed carbon. The ash content should be low, as being non-combustible it detracts from the calorific value of the fuel, and sulphur is detrimental as being destructive to the firebars. The coal should not be friable and should stack well. The tables on page 873 give the composition of some of the principal British steam coals.

Composition of Coal and Recent Scientific Research Thereon.—Coal being a complex colloidal organic substance of high molecular aggregation, requires for the elucidation of its chemical constitution the application of the best trained minds in organic chemistry, and although research work of late years has been greatly intensified in Great Britain, the United States, Germany, France and Canada, but little more has been discovered than was known at the commencement of the loth century.

Chemists employ three experimental methods for the investiga tion of the coal substance: (A) thermal decomposition, (B) fractionation by a sequence or combination of solvents, and (C) oxidation of the coal, hydrogenation, halogenation, etc. The prin cipal facts which have been established by these methods are : (A) M. J. Burgess and R. V. Wheeler (Chem. Soc. Trans., vol. xcvii., 1910; vol. xcix., 1911; vol. cv., 1914) by thermal decom position applied up to a temperature of i i oo° C determined :— (I) That the decomposition of the coal substance commenced about C ; (2) That in respect of the coals examined, whether bituminous, semi bituminous or anthracitic, there is a well-defined critical temperature between 700° C and 8o0° C which corresponds with a marked and rapid increase in the quantity of hydrogen evolved; and (3) That the evolution of methane and other paraffin hydrocarbons almost entirely ceases at about 700° C.

They concluded that the coals examined by them contained two types of compounds of different degrees of stability, viz., the "resinic" or less stable, which on thermal decomposition yield principally paraffins and no hydrogen, and the "cellulosic" which yield principally hydrogen. The facts hold good, but the inter pretation of them as given above is not universally accepted. For instance, H. C. Porter and G. B. Taylor, who have carried out researches on American coals (Proc. Amer. Gas Inst., vol. ix. [ 1 ], 1914) repudiate the suggestion that the "resinic" constituents of coal would be less than the "cellulosic" and attribute the great increase in the evolution of hydrogen between 70o° C and Soon C to secondary decomposition, and they found that more than two thirds of the organic substance of coals is decomposable below 500° C. Their views about the composition of coal are best expressed in their own words :— "All kinds of coal consist of cellulosic degradation products more or less altered by the process of ageing, together with derivatives of resinous substances, vegetable waxes, etc., in different proportions, more or less altered. They all undergo decomposition by a moderate degree of heat, some, however, decompose more rapidly than others at the lower temperature. The less altered cellulosic derivatives de compose more easily than the more altered derivatives, and also more easily than the resinous derivatives. The cellulosic derivatives decom pose so as to yield H20, CO2, CO and hydrocarbons, giving less of the first three products the more matured and altered they are. The resinous derivatives, on the other hand, decompose on moderate heating so as to yield principally the paraffin hydrocarbons, with probably hydrogen as a direct decomposition product. The more mature bituminous coals, having good coking properties, contain a large percentage of resinous derivatives and their cellulosic constituents have been highly altered. The younger bituminous or sub-bituminous coals are constituted of cellulosic derivatives much less altered than those in older coals. They undergo a large amount of decomposition below their fusion point, and possibly for that reason many of them do not coke." Prof. W. A. Bone pointed out (Soc. Chem. Ind., June 19, 1925) in his paper on the "Constitution of Coal," that in most recent coal research work little, if any, importance appears to have been attached to the nitrogenous constituents of coal, and there seems to be at least some room for doubt whether the supposed "resinic" constituents of coal have been rightly so called. He was inclined to think that our whole coal-nomenclature might be overhauled with advantage. Though there may be some doubt as to the feasibility of drawing a sharp line between the evolution of the various gaseous products in the case of a highly matured type of coal when under thermal decomposition, it is otherwise in the instance of an immature brown coal or lignite, as Bone's work has shown. The results being : (a) that up to a certain temperature (in the case of a dried sample of brown coal, from Morwell, near Melbourne, 375° C) the only gases expelled from the dried coal are steam and oxides of carbon, which evolution continues right up to (and perhaps beyond) 700° C ; (b) that at a somewhat higher temperature range (in the case of the Morwell coal, C) methane and other hydrocarbons (without oxygen) appear; and (c) it is not until the temperature exceeds 500° C that hydrogen appears among the products.

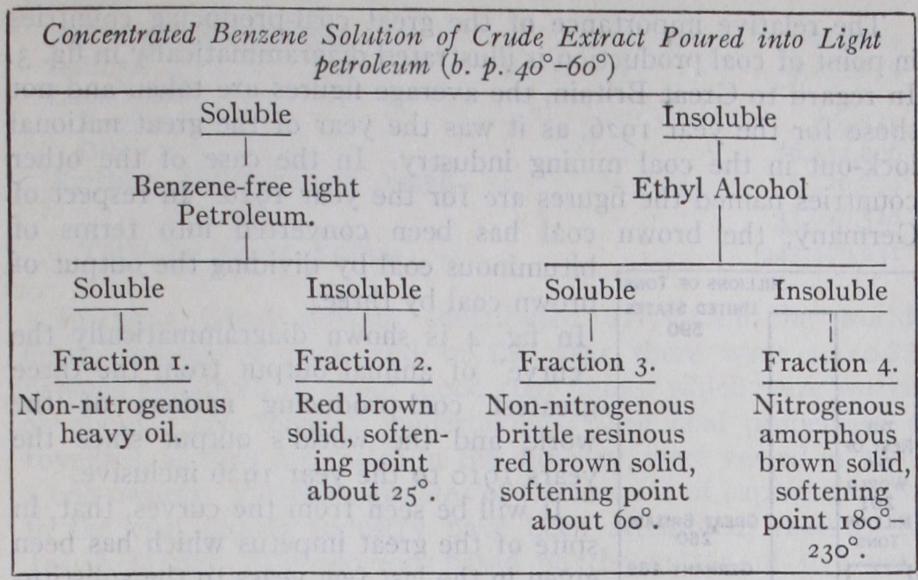

(B) In 1899, Bedson discovered the solvent action of pyridine on coal, and much later, A. H. Clark and R. V. Wheeler (Chem. Soc. Trans., vol. ciii., 1913) fractionated coal substance into three parts by first dissolving it with pyridine, then treating the pyridine extract with chloroform. The coal substance was divisible into: that insoluble in pyridine, (2) that soluble in pyridine but insoluble in chloroform, (3) that soluble in both pyridine and chloroform. These fractions are frequently referred to as alpha, beta and gamma constituents respectively, as though they were dis tinct and definitely separate chemical substances, which is un fortunate seeing that they all contain carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen and sulphur—in fact, nearly the same percentage of nitrogen and sulphur in each fraction. In the extraction of coal substances by benzene under pressure, Bone's work was of great interest. He employed benzene in a special form of extractor on the Soxhlet principle at pressures between 500 and 7001b. per sq. in. and at temperature 26o° to 285° C, and afterwards fractionated the extract by a suitable solvent treatment. He and his co-workers have by this means obtained four distinct benzene soluble frac tions (Proc. Roy. Soc., 105, Ser. A., 1924). This result is shown diagrammatically on the opposite page.

When working on a coking coal it was found that fractions 1 and 2 could be disregarded from the point of view of containing substances of a "binding" character. With regard to fraction 3, Prof. Bone said "the amount of this fraction was always very small, ranging between 0•3 and o.8% only of the whole coal sub stances; so that, although it has good `binding' properties, and therefore would be to some extent a contributary factor, it can not be considered as the chief cause of the coking properties of the coals." The substances contained in fraction 4 were different from the so-called "coal resins" and seemed to be rather of the "humic" type. Their chemical nature has not yet been finally established, but they constitute from 4.6 to 7.o% of the parent coal substance and have very pronounced "binding" properties, so that the rela tive coking properties of bituminous coals run nearly parallel to their yields of this fraction. These may therefore be considered as the chief cause of the coking properties of coals.

F. Fischer, H. Broche, and J. Strauch (Brenn,to ff -Cliem., 1925) in an account of similar experiments made upon German bituminous coals some little time after the appearance of Bone's paper, divided their crude benzene extract into two fractions only, which probably explains the apparent discrepancy in interpreta tion of the results. The benzene extracts from a brown coal are chemically different from those yielded by sub-bituminous or bituminous coal. It would seem that the coking quality of a coal is the result of the maturing of coal and is a product of age, for in black lignite there is evidence of the incipient formation of substances closely resembling the coking constituent of the more mature coals.

(C) Recent chemical research on the character of coal in cludes the work of Dr. Bergius, the German chemist, during the period 1915-25. By subjecting coal to the influence of hydrogen under heat and pressure, he saturates the hydrocarbons in the coal, converting them and, it is claimed, some portion also of the fixed carbon, into saturated hydrocarbons, thus achieving the lique faction of coal, the objective of chemists for many years. The process has not yet emerged from the laboratory stage, but should it prove a commercial possibility, the results on industry would be far-reaching indeed.