Zoa

ZOA and SCYPHOZOA.

2. The Medusa. Those Coelen terates popularly known as "jelly fish" are scientifically christened medusae, the name referring to the resemblance borne by the long mobile tentacles of some of these animals to the writhing, snaky tresses of the Gorgon Me dusa. The body of a medusa (fig. 3) is shaped like an um brella, and hanging down inside it from the point at which the handle of the umbrella would be attached, is a structure known as the manubrium, at the end of which is the mouth. In this case the tentacles form a circlet round the margin of the umbrella. For details of the organization of Coelenterate medusae reference should be made to the articles HYDROZOA and SCYPHOZOA.

Alternation of Generations.

One of the most interesting features connected with the Coelenterata is the fact that a single animal may for part of its life be a polyp and for part a medusa ; or from a polyp, buds may be formed which develop into medusae. In cases such as the latter it is the polyp which is developed from an egg, and this polyp itself produces no sex organs ; it is able however to give origin to vegetative buds which develop into me dusae, and these in their turn bring forth sex-cells which after fertilization initiate further polyps. In this way there is regu lar alternation between polyp and medusa and the phenomenon is termed metagenesis or alternation of generations.Polymorphism and the Formation of Colonies.—Another marked characteristic of the Coelenterata is their tendency to form colonies of individuals united to each other by a common stem, plate or mass of intermediate tissue. The colonies so formed are generally attached permanently to foreign surfaces, but in some cases they form strings or aggregations of individuals which float or are propelled through the sea. Coelenterate colonies are fre quently characterized moreover by the production in one and the same colony of different kinds of individuals, among which the various functions are distributed. There may co-exist in a single colony not only polyps as well as medusae (fig. 4), but more than one kind of each of these types of individuals. There may be sex ual medusae and medusae trans formed into locomotory organs; polyps whose main f unction is digestion and others which catch and paralyse prey; and so forth. The phenomenon thus outlined is known as polymorphism and metagenesis is a form of it ; it is one of the most interesting mani festations of the diversity of ani mal life, and is considered in more detail at the end of the article HYDROZOA.

Development.

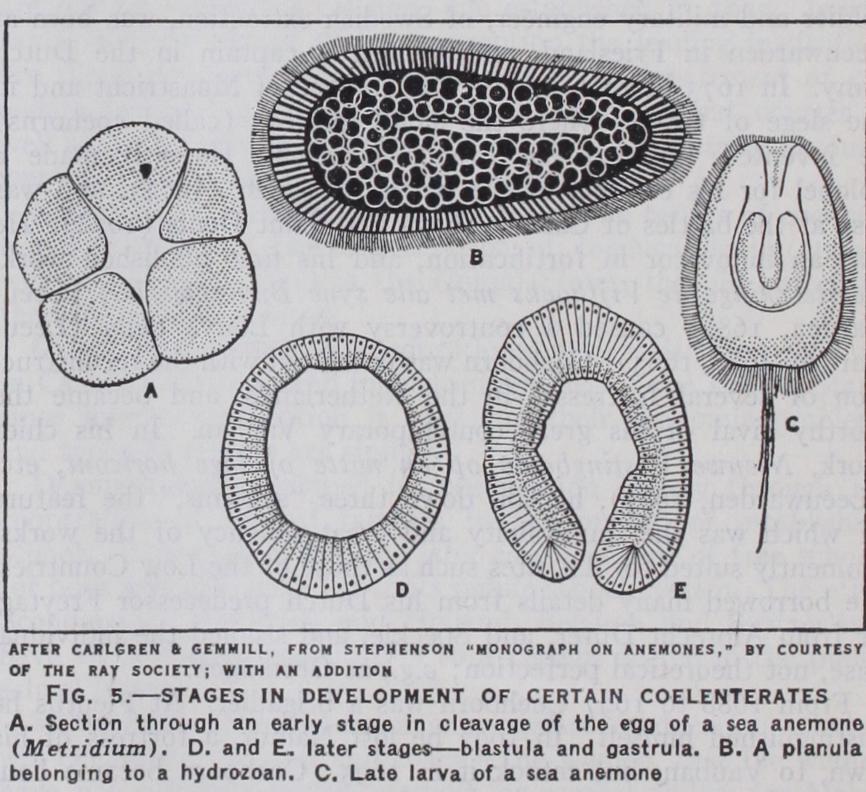

The Coelen terata pass during the course of their life-history through a series of stages very unlike the adult animal. A simple instance of these stages is provided by the embryology of the common sea anemone, Metridium senile (fig.5). In this species the eggs are shed into the sea by the parent and are there fertilized. After fertilization the egg divides into halves and each of these once more into two. The four cells (or blastomeres) so formed are equal or sub-equal in size. This process of subdivision is continued until a considerable number of small cells have been formed, and these are so arranged as to constitute a hollow sphere containing fluid. The sphere is known as a blastula and the cavity as a blastocoele. The blastula con tinues to develop in such a way that one side of the sphere first flattens and then becomes concave, being finally completely in vaginated into the other half. This process practically obliterates the blastocoele, and forms in its stead a second internal cavity, the archenteron, which communicates with the exterior by means of a small opening, the blastopore. There has thus been produced a typical gastrula such as has been previously described ; its archen teron becomes directly transformed into the coelenteron of the adult, and the blastopore becomes the adult mouth. During its early stages the animal moves through the water by the aid of cilia which appear on its outer surface during the blastula stage, but before it begins to assume the adult shape it tends to remain at the bottom, moving horizontally and resting from time to time and often becoming temporarily attached to the bottom mouth downwards, during which time it may execute slow creeping movements. From this larva the adult anemone-polyp is achieved by degrees. At a given time the larva settles down and attaches itself to a foreign surface ; its proportions change, it acquires ten tacles, and becomes a small polyp.

The embryology of the Coelenterata varies considerably from one species to another, but generally speaking it is characterized by the presence of a gastrula-stage or of some equivalent. Fre quently no actual gastrula exists but instead a corresponding stage known as planula is produced, in which there is no blasto pore, the embryo consisting either of a hollow two-layered organ ism or of a central mass of endoderm-cells covered externally by a layer of ectoderm (fig. 5) . Planulae and gastrulae may be free-swimming organisms moving by means of cilia, or may be contained within the coelenteron of the parent or within a pro tective enclosure so that they have no actual free existence, and are born as young polyps.

Motion.—The movements of which a Coelenterate is capable depend upon its shape, organization and mode of life. A jellyfish is an active free-swimming creature which progresses through the water as a result of rhythmic or spasmodic contractions of its bell-like body brought about by the action of muscles. Different kinds of jellyfish are active in varying degrees; some are much stronger swimmers than others, some are decidedly sluggish, whilst a few are creepers. Movement in polyps varies according to whether they possess a skeleton or not ; in those provided with such a structure movement is naturally limited to those actions which the tentacles or other parts of the polyp can perform unre stricted by the hard parts. If a polyp is free from skeleton, it can move in a variety of ways; rarely, it swims actively by concerted lashing movements of the tentacles ; sometimes it will creep on these organs ; or it may attach itself by the base, bend over and attach the tentacles, then loosen the base, move its body and re-attach the base elsewhere. On the other hand it may simply loosen its hold and allow the motion of the water to carry it else where, and in such case may inflate itself with water in order to become more buoyant; or it may creep upon its base, a method characteristic of many of the large polyps of the sea anemones.

The movements exhibited, apart from those connected with actual locomotion, consist of contractions and expansions of the tentacles and body, movements of the mouth, and so forth, con nected with capture and swallowing of food, with retraction for the purpose of sheltering from adverse conditions, and with simi lar matters. Tentacles are usually highly contractile, and in their most concentrated condition are very much smaller than when expanded. The whole body may be relatively rigid and not, as a whole, very contractile, in forms possessing a high development of the mesogloea ; but in many cases it is as contractile as the tentacles and may be reduced at need to a bulk very much smaller than its size when expanded; e.g., to an eighth of its maximum bulk.

Muscles.—Although the general substance of a Coelenterate is contractile, the definite movements which it performs are the result of muscular or ciliary action. The muscular system in its simplest condition consists of a single layer or sheet of muscle fibres, lying on the inner or outer surface of the mesogloea. The muscle-sheets of Coelenterates are normally only one fibre thick, and each fibre lies directly upon a supporting surface of meso gloea. Consequently if strong localized muscles (as distinct from diffuse sheets) are required, these are generally attained by the simple expedient of pleating the surface of the mesogloea into ridges, on the surface of which lie the fibres, still in a single layer. In certain cases muscle becomes embedded in the mesogloea. The individual fibres are not in the simpler instances independent structures, but belong to and form part of epithelial cells of the ectoderm or endoderm. Thus the combination of each cell with its "muscle tail" (or tails) constitutes a musculo-epithelial cell, a structure characteristic of Coelenterata but rare among higher animals (fig. 8). In more specialized cases the muscle-fibres of the ectoderm become separate structures, the epithelial cells which produced them being of insignificant proportions.

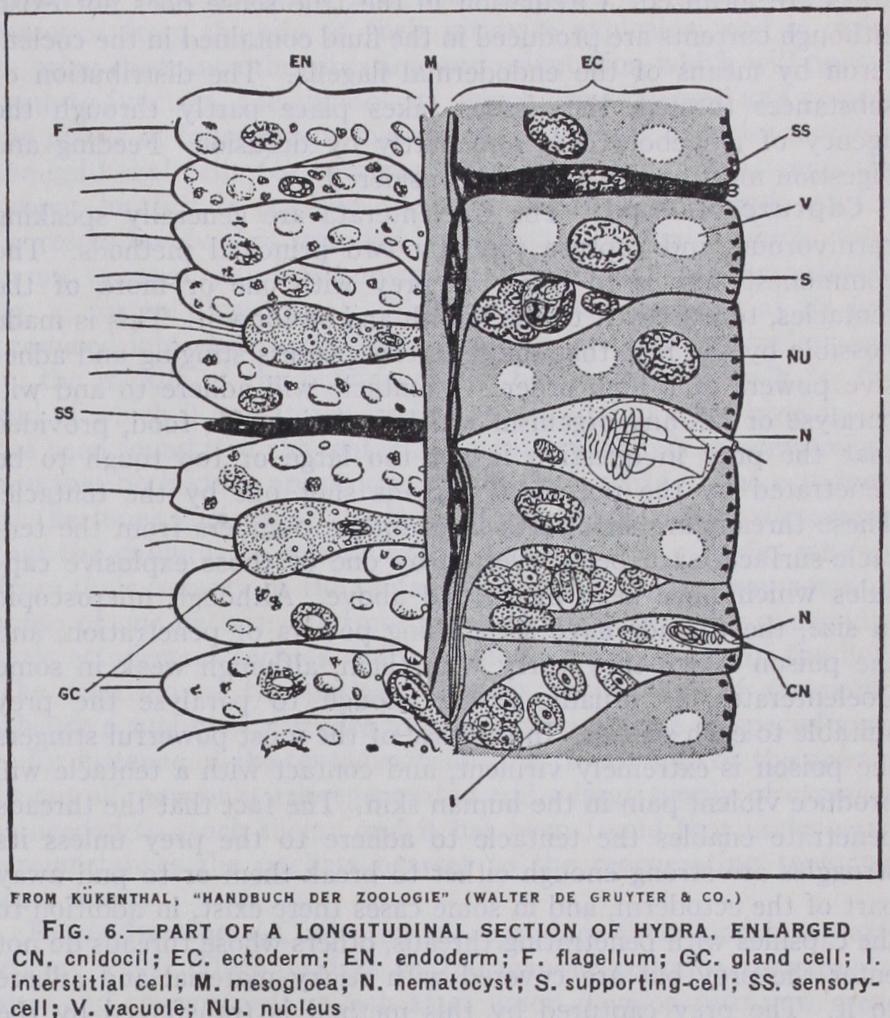

The Finer Structure of the Tissues.—The structure of the layers of the body must now receive short notice (fig. 6). The mesogloea is a sheet of very variable structure ; sometimes it is gelatinous in texture, sometimes almost cartilaginous, or again it may be very watery and unsubstantial. It contains within its substance cells which have wandered there from the other layers, and the functions of which are not fully understood. Some of them at least are amoeboid cells which carry or transmit nutri ment from the endoderm (the digestive layer) to other parts of the body. Others probably add to the mesogloeal substance by secretion, whilst it is possible that some of them constitute part of a mesogloeal nervous system. At its highest development the mesogloea possesses fibres as well as cells, but these are not at all of the same nature as the muscular fibres. The cell-layers are best considered separately, and the following details apply to a sea anemone, which will serve as a suitable example. The ecto derm is an epithelium consisting of elongated supporting cells which are ciliated in some parts of the body, and among these occur large numbers of cells of other kinds. There are glandular cells which secrete mucus, etc., sensory cells which constitute the peripheral receptive elements of the nervous system, cnido blasts which secrete curious explosive capsules about which more will be related shortly, and undifferentiated interstitial cells which may give rise to other kinds at need. In the deeper parts of the epithelium lie nerve cells (the nervous system is further described below) and on the surface of the mesogloea, in given parts of the body, are the muscle fibres, which are here inde pendent of the supporting cells. The endoderm resembles the ectoderm in general constitution, but its supporting cells, instead of being ciliated, bear each a single large cilium or flagellum, and each possesses a basal muscle fibre, and so constitutes an epithelio muscular cell. Many of them are digestive in function. Gland cells are to be found in the endoderm, as also are sensory, nervous and interstitial cells ; cnidoblasts are most characteristic of the ectoderm, but also occur freely in the endoderm where necessary.

The germ cells of the Coelenterata, those cells which will in due course form eggs or spermatozoa, are formed sometimes from interstitial cells, sometimes from differentiated epithelial cells. They may originate in either ectoderm or endoderm, but are not necessarily first formed in the region in which they will ripen.

General Functions.

The Coelenterata possess no special organs for respiration or excretion, and possess neither blood nor blood-vessels. Respiration and excretion are performed by the general surfaces of the body, but sometimes the chief excretory areas are localized. Circulation in the true sense does not exist, although currents are produced in the fluid contained in the coelen teron by means of the endodermal flagella. The distribution of substances through the tissues takes place partly through the agency of amoeboid cells and partly by diffusion. Feeding and digestion must be more closely considered.

Capture of Food.

The Coelenterata are generally speaking carnivorous, and capture food by two principal methods. The commonest way is to seize the prey with one or more of the tentacles, to convey it to the mouth and swallow it. This is made possible by the fact that the tentacles possess stinging and adhe sive powers of a high order. A tentacle will adhere to and will paralyse or kill any organism which is desired for food, provided that the prey in question is not too large or too tough to be penetrated by the poisonous threads shot out by the tentacle. These threads are shot forth in countless numbers from the ten tacle-surface, each being everted by one of those explosive cap sules which have been mentioned above. Although microscopic in size, the threads have astonishing powers of penetration, and the poison which they carry with them, although weak in some Coelenterates, is usually strong enough to paralyse the prey suitable to each species. In the case of the most powerful stingers the poison is extremely virulent, and contact with a tentacle will produce violent pain in the human skin. The fact that the threads penetrate enables the tentacle to adhere to the prey unless its struggles are strong enough either to break them or to pull away part of the ectoderm, and in some cases there exist, in addition to the capsules with penetrating threads, others whose threads do not enter the prey but are covered with sticky material and adhere to it. The prey captured by this method is transferred by the tentacles to the mouth, which is generally very extensile and can open widely so as to engulf objects which in some cases are enor mous in relation to the size of the swallower. The Coelenterate has not necessarily finished stinging the prey after it has been taken in, for in many cases there exist internal stinging organs.There is another method of feeding which may supplement or replace the characteristic one. Small food-particles which come in contact with some part of a Coelenterate become entangled in slime secreted by that part, and these are transported by means of cilia acting in definite directions to the mouth. This method of feeding is probably the predominating one—for instance, in certain sea anemones—and a good example of its working may be seen in the jellyfish Aurelia. (See article SCYPHOZOA for an illustration.) When Aurelia is feeding, planktonic organisms be come entangled in strings of slime on the outside of the swim ming-bell, and are conveyed by the movements of the bell aided by the action of cilia to the edge of the umbrella. Arrived at this point they are concentrated into eight masses at points situated at regular intervals round the margin of the bell. From time to time these masses are licked off by one or other of the four large arm-like processes which hang down under the bell round the mouth; and since each of these arms contains a groove leading directly into the mouth, the food-mass is from this point onwards easily transported into the stomach. The underside of the swim ming-bell also contributes to the eight food-masses and the oral arms themselves collect plankton independently. This seems to be a normal mode of feeding in Aurelia, but at the same time it can and does, at any rate when young, catch fishes and other organisms as well as plankton.

The Food of Coelenterata.

The food of Coelenterates includes a great variety of animals—fishes and their eggs, crabs and all manner of other crustacea, worms, molluscs, other Coelen terates, etc., not to mention the innumerable small planktonic organisms imbibed. Some Coelenterata are omnivorous, but others again will select their food more or less definitely. Certain special forms feed upon unicellular Algae (Zooxanthellae).

Digestion.

Digestion in Coelenterates is a process involving two stages. If a large object has been swallowed it is first broken up into particles and the latter are then engulfed or ingested by individual endoderm cells within which each particle becomes sur rounded by a fluid-containing vacuole and there the remaining processes of digestion and absorption take place. Thus the whole process involves first extra-cellular digestion in the coelenteron. and then intracellular digestion in the endoderm ; or if the food is small enough it may be directly ingested by endoderm-cells without previous breaking down. The details of this process vary according to the anatomy of the Coelenterate in question. In a simple case such as that of Hydra, the coelenteron is lined by a simple and fairly uniform layer of endoderm, not concentrated into special structures; and in such case this layer performs the double function of secreting digestive material which will break up a large prey and of ingesting the fragments so produced. In a higher form such as a sea anemone or coral the endoderm is differentiated into regions; there are definite tracts of epithelium in which gland-cells are concentrated, and these constitute together with the adjacent endoderm the main digestive area. These tracts, the mesenterial filaments, have been shown to secrete a digestive juice ; and although they may also themselves ingest, in the most specialized cases the main absorptive region is not the filament itself but the endoderm on either side of it. The area of endoderm which will ingest food in such cases varies according to the size of the meal. The digestive ferments of Coelenterates are generally speaking specialized for dealing with animal prey.

Nervous System.

This is of a very primitive grade in terata, and possesses neither actual nerves nor any central ling organ. Its essential parts are the sensory cells of the derm and endoderm, together with a network of fine fibrils necting those cells with the muscle fibres and with nerve cells. The cells and fibrils constitute a "nerve net" which runs in the deeper part of the epithelium (fig. 7) and perhaps also penetrates the mesogloea. The net is sometimes fairly evenly distributed, sometimes better developed in one part than in another, and times decidedly concentrated in given regions. Its action is cially characterized by the fact that it confers autonomy upon given parts of its possessor, so that these will function in the absence of the remainder (e.g., the basal half of a horizontally divided sea anemone will execute creeping movements in the absence of the head-end) and by the further fact that an impulse is believed to travel in any direction through the net, this trasting markedly with the one-way mission to which a more highly organized nervous system is restricted. This has been demonstrated experimentally by ing elaborate preparations from the brella of living jellyfish in such a way as to restrict the nerve net to figures of given shape. So long as organic continuity from point to point is maintained in any given figure an impulse started at any point will spread throughout the system. In certain Coelenterata the nerve net exhibits locally signs of a higher differentiation than this. Many Coelenterata possess definite sense-organs. These are naturally found in the more active members of the group, that is to say the medusae; they are sent altogether in the polyps. The chief types of sense-organ are two in number, and these are described in connection with the animals possessing them, in the articles HYDROZOA and SCYPHOZOA. The first type includes organs tive to light and termed ocelli; and these structures, though often simple, may attain at their highest development the grade of eyes (see Charybdaea, in SCYPHOZOA). The second type prises organs of variable structure (statocysts and tentaculocysts) which include hard particles (statoliths) in their constitution, and whose function is not yet fully understood. Although they might be expected to be organs of balance this does not appear to be actually the case. It has been ascertained experimentally however, that certain of these organs initiate the stimuli which produce the swimming-contractions of the bell of the medusa possessing them, and consequently control the rate of pulsation. The bell pulsates at the rate of whichever organ is initiating stimuli most rapidly at a given time. The sense organs also appear to exert an influence on the general metabolic activities of the animal.

Stinging Capsules.

The cnidoblasts with their explosive cap sules or cnidae will now be described (fig. 9). These capsules are among the most extraordinary structures to be found in the ani mal kingdom, and the physiologi cal problem presented by the question of their explosion is a difficult one. It is probable that several factors are involved, and that these are called into play in fluctuating intensity according to the structure of the capsule and cnidoblast in question. Each cnida is a ref ringent transparent capsule with a gelatinous or more probably fluid content. In unexploded state, the capsule contains a hollow thread (i.e., a capillary tube of incredible fine ness) coiled or folded up within it ; and the wall of capsule and thread are continuous with one another at one pole of the capsule. The cell (cnidoblast) in which the capsule lies and which originally produced it, bears at its free surface a fine hair-like projection, known as a cnidocil. The contact of a foreign body with this cnidocil leads directly to the explosion of the capsule, but it is possible that this can also be effected by the nervous system. On the other hand such contact does not necessarily explode the capsule. For instance the reactions of a well-fed sea anemone are not the same as those of a hungry one; the tentacles may refuse food altogether, neither the tactile nor the chemical stimuli in volved producing any effect on the capsules. When, however, a capsule does explode the thread is shot forth instantaneously. Al though the action is so rapid, the thread as it is ejected turns com pletely inside out, in the manner in which one may turn the finger of a glove ; in other words it is evaginated.The structure of both cnidae and cnidoblasts varies greatly from one Coelenterate to another, and both may be complex. The cnidoblast possesses, in a number of cases at least, contractile fibres of varying disposition, and may also contain a coiled spring like structure (the lasso) which probably resists the tearing away of the nematoblast from the tissues by a struggling prey. In a typical cnida the thread is provided with a series of spirally arranged barbs which help to fix it in the tissues of the prey, and bears with it poison which enters by the wound it has made. This kind of cnida, which is very frequent, is known as a nematocyst, in contrast to another type common in sea anemones and known as a spirocyst. The latter has no armature, but the outer surface of its evaginated thread has strongly adhesive properties, and is probably not poisonous.

True cnidae occur nowhere in the animal kingdom save in the Coelenterata. There are similar structures developed in at least two other kinds of animals (the Myxosporidean Protozoa and certain Nemertine worms), but they are not exactly the same; a number of other structures which have been confused with nema tocysts are not actually such. The most interesting cases which have been investigated in this connection are those of certain animals in whose tissues actual Coelenterate nematocysts are pres ent in an unexploded and functional condition. It has been con clusively shown that an animal may feed upon a Coelenterate, thus swallowing quantities of nematocysts, and that a number of these may pass unexploded through its food-canal, and may sub sequently become arranged in a definite manner in its tissues. The best known instance of this is provided by certain of the Nudibranch molluscs or sea slugs. In some cases at least these stolen nematocysts appear to be of value to their host.

Nematocysts and spirocysts, which are produced by interstitial cells, are not developed in the place where they will function. In some cases this means simply that they develop in the deeper layers of the epithelium and move up to the surface as they mature. In other cases however a much more interesting story is involved. The capsules are here secreted by cnidoblasts far removed from the site of their ultimate explosion, and in order to bring them into the situation and orientation which will permit them to function, the cnidoblasts, which are amoeboid and possess the power of independent movement, drag their capsules between the epithelial cells (or transport them by other means) until the proper locality is reached. A most interesting example of the processes involved is supplied by the state of affairs which exists in an unusual jellyfish known as Haliclystus (see SCYPHOZOA, fig. 4, for an illustration). This animal has the edge of its bell produced into eight arms, each tipped by a tuft of tentacles; and on the middle of the outside of the bell it bears a stalk by the end of which it can attach itself to seaweed and other objects. It has been found that the tentacles contain two kinds of nematocyst, and that both kinds are produced in definite parts of the ectoderm of the inner surface of the bell. It has further been discovered that the cnidoblasts containing the two kinds of capsules migrate from their nursery to the tentacles; but that on the way some of those of one pattern (and not those of the other) disappear into little ectodermal pockets which lie close to the margin of the bell. The function of the pockets appears to be that of reservoirs whence a supply of capsules may be drawn in case of special need —for instance, if the tentacles belonging to one side of the animal be cut off, new ones are regenerated and a large supply of capsules is needed to stock them ; and it has been found that under such circumstances the pockets nearest to the regenerating tentacles were empty.

Reproduction.

Coelenterates reproduce their kind in a ety of ways. They produce in the manner common to animals, eggs and spermatozoa, which after union develop into new tures. But in addition to this universal method they have an extraordinarily strong tendency toward "vegetative" or asexual modes of reproduction, and related with this a very marked ability to regenerate lost parts. This manner of increase is much like the ability of a plant to produce runners. It exists under a variety of forms; sometimes an animal within the space of a few hours or less will tear itself completely in half tically; each half will regenerate new parts and will so develop into a complete animal. This process is known as fission; it does not always take the form of actual tearing, but may result from a gradual process of striction whereby an individual separates either completely into halves or becomes partly double. In other varieties of fission the separation into two or more parts takes place horizontally ; and again, neither in vertical nor zontal fission does it follow that the pieces formed will be at all equal in size. Equally characteristic of Coelenterates, but generally speaking of different ones, is the process known as budding (figs. 4 and io). In this case a polyp may send out a rootlet (like the strawberry-runner) at the end of which a new polyp grows up; or a new polyp may arise direct from the tissues of an existing one. Polyps give rise by budding to other polyps or to medusae; medusae by budding may produce fresh medusae but never polyps, these being always developed from eggs or from other polyps. The processes of regeneration which succeed certain types of asexual reproduction are both definite and interesting ; and the regenerative results which arise from the cutting away of various parts of Coelenterates, or from the division of these animals into portions by cuts in different directions, provide material for a study from which much of general biological interest may be gained. Further details relating to budding and fission will be found in the articles HYDROZOA, SCYPHOZOA, and ANTHOZOA, whilst for information relating to regeneration reference should be made to the article on that subject.

Commensalism and Symbiosis.

There are to be found among the Coelenterata a number of examples of those types of relationship between one organism and another which are respec tively known as commensalism and symbiosis. Commensalism, as exemplified by the regular partnership which exists between cer tain sea anemones and hermit crabs, is well represented in the group (see also next section) ; and a number of Coelenterata con tain in their tissues those unicellular symbiotic Algae known as Zooxanthellae.

The Poison of Coelenterates.

A certain amount of work has been done on the lines of making extracts of one sort and another of the tissues of Coelenterates and injecting these into other ani mals in order to study the effect of the poison of the Coelenterate on the animal in question. It has been known for a long time that the poisons of certain Coelenterates are very virulent and that contact of the stinging organs with human skin may produce serious results. In the case of medusae belonging to the Charyb daeidae for instance, jellyfish which outstrip all others in the strength and rapidity of their swimming-movements, the stinging organs may cause intense pain after contact with the skin, and symptoms such as swelling of the legs, etc., follow ; fatal results may even ensue. A recent investigation of particular interest has been made on the poison of Adamsia palliata, which not only throws light on the question of Coelenterate poisons but also upon the relationship between this anemone and another animal. Adamsia palliata lives in permanent association with a hermit crab known as Eupagurus prideauxi, and apparently these two organisms never normally occur apart. The soft tail-end of the crab is protected by the ane mone, which is wrapped round it like a cloak; and the mouth of the anemone lies just below that of the crab, so that meals be come a communal affair. Now it is possible to make an extract containing the poison of the ten tacles or other stinging organs of an Adamsia, and such extracts have been injected in varying strengths into a number of ani mals. Certain of these, for instance Cephalopod molluscs (cuttle-fishes, etc.) and other sea anemones, appear to be com pletely immune from the Adam sia poison ; other animals suc cumb to it. It has been found that the Decapod Crustacea (crabs, etc.) are the most sensi tive to it, and its action on a number of these has been studied.The following experiment is a case in point. Three shore-crabs (Carcinus maenas), three common hermit-crabs (Eupagurus bernhardus) and three of the hermits proper to Adamsia (E. prideauxi) were selected, and into the body-cavity of each was injected o•Ic.c. of a filtered maceration of Adamsia. At the end of three minutes the bernhardi were completely paralysed after a short phase of tetanization; and at the end of an hour they were dead. The shore-crabs died between five and nine hours after having exhibited the symptoms characteristic of this poison. On the other hand the prideauxi showed no apparent trouble ; they retained all their agility and all the accustomed vivacity of their movements. At the end of 24 hours their condition was normal and they survived indefinitely. Other experiments confirm the result of this one, and the interesting fact emerges that E. pri deauxi is immune from the poison of its anemone unless injected in inordinately large amount. Thus the association between the two animals includes a physiological as well as a morphological adaptation. It has been shown further that the serum of E. prideauxi is able to neutralize the Adamsia poison and that if a shore-crab be inoculated with prideauxi serum, it can afterwards withstand and recover from a dose of poison which would other wise be fatal. It is probable that E. prideauxi gains its immunity in the first instance as a result of the fact that its close association with the anemone involves the constant entanglement of small portions of the latter, or of stinging cells derived from it, in the hermit's food. The intestinal content of the hermit usually con tains such fragments of the anemone. Although in these experi ments the poison of Adamsia did no harm to other anemones, yet in other cases one anemone may sting another, even of the same kind, and produce a wound which may prove fatal—so that an anemone is not necessarily immune from poison produced by its own kind. It is possible, however, that the injured animal in such cases is, to begin with, in a poor condition.

Distribution, Environment and Length of Life.

The dis tribution of the Coelenterata is world-wide, but the great majority are marine; a few kinds only inhabit brackish or fresh water, and these are further mentioned in the articles HYDROZOA and ANTHO ZOA. The mass of Coelenterata then, inhabit one or other of the regions of the sea ; and it cannot be said that they are charac teristic of one kind of habitat more than of another. Many of them inhabit the littoral zone between tide-marks. Others colonize the sea-floor at greater or lesser depths, some of them occurring in extremely deep water (e.g., 2,90o fathoms). The remainder are pelagic at varying depths and may live in the open sea, some of them floating and some swimming. A number of Coelenterates are perennial, living for a number of years, their length of life in some cases probably being extremely great. The best measured example of this is that of some sea anemones at present alive, which are known to be at least 7o years old and may be much more. Other Coelenterates, on the other hand, are seasonal; many hydroids die down in winter and regenerate new polyps in spring; and many medusae live for a brief period only. Neither the tropics nor the cold regions can be regarded as the more typical habitat for Coelenterata, though it is true that corals, anemones and Siphonophores for instance, attain their maximum profusion or considerable complexity of development (sometimes both these features) in the warm seas. The variety of Coelenterates which may occur within a broadly similar environment is great, but as in the case of many other animals a certain proportion at least of the genera permanently colonizing the various available habi tats show a sympathetic reaction to their environment ; thus it may be expected with reason that an average anemone living at great depths will be different from a typical inhabitant of a coral reef, and a typical mud-dweller from an ordinary adherent form. Certain single species however range in suitable habitats from the Arctic to the Equator, others occur both in the Arctic and the Antarctic ; whilst some are circumpolar is distribution. With regard to the distribution of jellyfish it may be noted that their swimming powers are adapted rather for maintaining their posi tion in the water and for moving up and down in it than for making long journeys; the main agents in their distribution are currents and tides.

Classification.

The Coelenterata are divided into three great classes, the Hydrozoa, Scyphozoa and Anthozoa. To these are sometimes added the Ctenophora; but the latter are animals which are actually very different from any Coelenterata, and the reasons which lead to this conclusion are stated in the article dealing with them. The characteristics of the three great classes of Coelen terata are also described in articles dealing with each series separately.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-General

Accounts: E. A. Minchin, G. C. BourneBibliography.-General Accounts: E. A. Minchin, G. C. Bourne and G. H. Fowler, "The Porifera and Coelentera," in A Treatise on Zoology, pt. 2 (ed. Sir E. Ray Lankester, 1900) ; Y. Delage and E. Herouard, Tr me de zoologie concrete, vol. ii., pt. 2 (19o1) • S. J. Hickson, "Coelenterata and Ctenophora," in Camb. Nat. Hist., vol. i. (ed. A. E. Shipley and S. F. Harmer, 1906) ; H. Broch, T. Krumbach, W. Kiikenthal, F. Moser and F. Pax, in W. Kiikenthal, Handbuch der Zoologie, vol. i. (ed. T. Krumbach, 1923-25) .Development: E. W. MacBride, "Invertebrata," in W. Heape, Text-Book of Embryology, vol. i. (1914). Histology: K. C. Schneider, Lehrbuch der V ergleichenden Histologie der Tiere (Jena, 1902) and Histologisches Praktikum (Jena, 1908). Nematocysts: L. Will, Natur forschenden Gesellschaft (Rostock, 1909-1o) ; P. Schulze, Archiv fur Zellforschung, with bibl. (ed. R. Goldschmidt, Leipzig, 1922) ; and in animals other than Coelenterata: C. H. Martin, Biologische Centralblatt (ed. J. Rosenthal, Erlangen, Leipzig, 1914). Nervous System and Behaviour: G. H. Parker, The Elementary Nervous System (1919). Digestion: H. Boschma, Biological Bulletin (Woods Hole, Mass., 1925) ; R. Beutler, Zeiischr. f iir vergl. Physiol. (1924-26) . See also H. Boschma, etc., for Zooxanthellae. For recent lists of literature see W. Kiikenthal's Handbuch (supra), and for further references the articles HYDROZOA, ANTHOZOA and GRAPTOLITES. (T. A. S.)