Colour Measurement Munsell System

COLOUR MEASUREMENT (MUNSELL SYSTEM). The first essential to the application of the Munsell Colour System is a clear understanding of the three dimensions of colour, and once having grasped the simple logic of these, the practical advantages of the system will be manifest. Colour has three dimensions—Hue, Value, and Chroma, which fully and accurately describe any colour as readily as the three dimensions of a box describe its length, width, and height. The idea of the three dimensions of colour may be expressed thus: With these three simple directions of measurement well in mind, there need be little confusion in comprehending what is meant by colour measurement.

Hue.

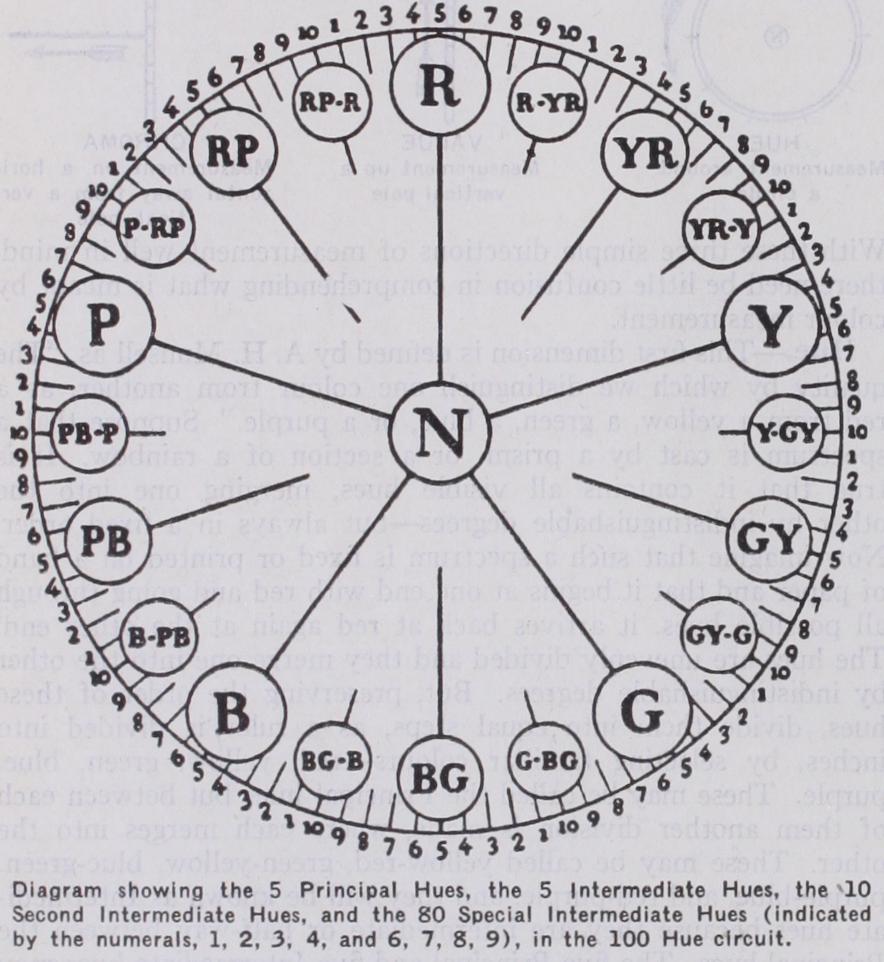

This first dimension is defined by A. H. Munsell as, "The quality by which we distinguish one colour from another, as a red from a yellow, a green, a blue, or a purple." Suppose that a spectrum is cast by a prism, or a section of a rainbow. It is true that it contains all visible hues, merging one into the other by indistinguishable degrees—but always in a fixed order. Now imagine that such a spectrum is fixed or printed on a band of paper and that it begins at one end with red and going through all possible hues, it arrives back at red again at the other end. The hues are unevenly divided and they merge one into the other by indistinguishable degrees. But, preserving the order of these hues, divide them into equal steps, as a ruler is divided into inches, by selecting familiar colours—red, yellow, green, blue, purple. These may be called the Principal hues but between each of them another division is made, where each merges into the other. These may be called yellow-red, green-yellow, blue-green, purple-blue, and red-purple, and they will be known as Intermedi ate hues because they are intermediate or half-way between the Principal hues. The five Principal and five Intermediate hues may be called the major hues. Now, if this band is bent into a circular hoop, so that the red at one end meets and laps the red at the other end, there has been constructed a perfect scale of hue in the cir cular form, with the five Princi pal hues opposite the five Inter mediate hues. The circle of hues with the five Principal hues and five Intermediate hues is shown in this form in the accompanying colour plate. The selection of five colours for the Principal hues is based on their complementary hues as determined by "after image." The five Principal hues and their complements, the five Intermediate hues, divide the hue circle into ten parts—visually equidistant one part from another and readily expressed by the decimal system. So it is that when one states the first dimension of a colour, one is referring to its position on this circular scale of hues. In writing a colour notation, this first dimension is expressed by the initial letter of the hue—R for red, a Principal hue, and BG for blue-green, an Intermediate hue.These ten steps being decimal numbers, may, of course, be in finitely subdivided and it may frequently happen that a given colour does not fall exactly on any of these ten divisions of hue, but somewhere between two of them. Allowance has been made for this by dividing each of the steps of the Principal and Inter mediate hues into ten further divisions—called Special Intermedi ate hues. These ten subdivisions represent about as fine a varia tion of hue as even a trained eye can distinguish, and it would be obviously futile, for practical purposes, to carry it further. The numerals run from i to io, 5 always marking a Principal hue or an Intermediate hue and to always falling half-way between a Principal and an Intermediate hue. Thus the system has a series of numerals denoting any practical step or gradation between one hue and another and in writing a colour notation, of which one of these special Intermediate hues is a part, the numeral is given, denoting the position of the hue on this scale, before the letter which stands for the nearest Principal or Intermediate hue, thus R, 3 YR, 2 Y. The ten major hues then are expressed: 5 R, 5 YR, 5 Y, etc. The notation i o R may also be expressed as Red Yellow-Red, it being half-way between these two hues, similarly Jo Y becomes Yellow Green-Yellow, etc.

These are called Second Intermediate hues.

It should be remembered that the hue Red embraces all reds whether light or dark, weak or strong, its hue merely determines its point on the spectrum hue circle.

Value.

This is the second dimension and is probably the sim plest to understand. It is, according to Mr. Munsell's definition, "The quality by which we distinguish a light colour from a dark one." Note that the first dimension did not tell whether a colour was light or dark. It told, for example, that it was red and not green, but there may be a light red and a dark red, and it is the function of this dimension of Value to tell how light or how dark a given colour may be. For this purpose a scale of Value is needed, which may be imagined as a vertical pole or axis to the circle of Hues, black at the lower end, representing total absence of light, and white at the top, representing pure light, and between these a number of divisions of grey regularly graded between white and black. This gradation could also be infinite. Since pure black is unattainable, it is called zero and the scale begins with the darkest grey as one, numbering the steps up to nine, which is the lightest grey. Pure white, which is also un attainable, may be called ten. In the prac tical use of the scale of Value, therefore, there are but nine steps and the middle one of these is five—which is referred to as Middle Value. The Value scale is shown in this form in the accompanying colour plate with proper divisions between black and white. In writing a colour nota tion this dimension of Value is expressed by a numeral, which denotes at which step on the scale of Value the colour falls. This numeral is written above a line, as B 6/ for example, by which is meant that this particular blue, regardless of its other qualities, is as light or as dark as the sixth step upon the scale of Value. A colour such as is called "maroon" is an example of a red which is low in value, because it is dark, and what is called a "pink" is a red which is high in value, because it is light.

Chroma.

When it is stated that the colour is blue or yellow or green, and that it is dark or light, two of its important qualities are indicated—its Hue and Value, but this by no means describes it completely. It may be said of a flower that it is red and that it is light, but it may also be said that a certain brick is red and also light, and yet there is a notable difference between their respective colours, if they are placed side by side. Both may be red and of the same Value, but the flower is strong in colour and the brick is weak in colour, or greyer. It is this differ ence which is measured on the dimensions of Chroma. This di mension is the measure of the strength or weakness of a colour. The scale of Value may be referred to in the convenient and easily understood form of a vertical pole, which represents the neutral axis of all the circle of Hues and is, of itself, of no colour, but is pure grey. Around this pole may be placed the band representing the scale of Hue and then any one of these hues on the cir cumference of the hand may be imagined as grow ing inward toward the grey pole in the centre, growing greyer or weaker in colour strength until it reaches this centre pole and loses its colour en tirely. This gives a visual ization of the idea of the dimension known as Chroma. By dividing these bands into regular measured steps, one has a scale upon which the strength of colour may be measured. This dimension of Chroma is written in a colour notation by means of a numeral below a line, which denotes the step upon the Chroma scale at which it falls, thus /2, /4, /8, /1o, etc.Needless to say, all of the Hues may be thus measured on this dimension at right angles to the vertical pole and grading from grey, step by step away from the pole to greater and greater strength of colour.

A complete Chroma chart of red is shown on the colour plate; on this chart the vertical scale of Value is repeated to emphasize its position in relation to Chroma.

There are two important facts which should be considered. First, colours differ by nature in their Chroma strength, some be ing much more powerful than others. The strongest red pigment used, for example, is approximately twice as powerful as the strongest blue-green pigment and the red pigment will, therefore, require a correspondingly greater number of steps on a longer path to reach grey. The second fact is that all colours do not reach their maximum Chroma strength at the same level of Value. It can be readily comprehended, for example, that the strongest yellow pigment is by nature much lighter, or higher in Value, than the strongest blue pigment and, therefore, the com plete Chroma paths of these two colours will each touch the neutral pole at different values.

The form, which conveys most completely the character of colour qualities and dimensions governing the range of pigments in regular use, has been conceived by A. H. Munsell as a "Colour Tree." The "Colour Tree" has for its trunk the vertical scale of Value and the branches represent the different hues arranged radially about the trunk, these branches varying in length with the Chroma strength of each hue. A colour tree is shown in this form in the accompanying colour plate—the vertical scale of Value in the centre with the ten major hues are shown only at the Value level at which they reach their strongest Chroma. If each hue was shown at every level of Value the figure would become a solid with the strong colours outside gradually becoming greyer until they reach the grey Value scale.

Each of the three dimensions by which any colour may be meas ured has been described, and also how each is written in a colour notation. It remains only to put these separate notations together and to write a complete notation embodying all three dimensions. For example, given a certain colour to measure and define, it is found that upon the scale of Hue it is Purple-blue. Upon com paring it with the scale of Value, it is seen to be but three steps from the bottom, and two steps away from the neutral grey pole upon the scale of Chroma. A complete notation for this colour would, therefore, be written PB 3/2. It is scarcely necessary to point out the practical advantages of such a system of definite measurement and notation over the vague and variable terms in general use, borrowed from the animal, mineral, and vegetable kingdoms, such as plum, olive, fawn, mouse, etc., of which no two persons ever have quite the same idea.

The Use of Colour.

Contrast in Value is, perhaps, the most important factor in a composition or design. Value difference alone without regard to Hue or Chroma may make or mar the result. Value contrast will make lettering or type, for example, legible or illegible. A colour of middle Value will be least dis tinguishable on another colour of equal Value and the greater the contrast in Value the better the legibility.Maximum contrast is obtained by the use of colours of ex tremely strong Chromas if they differ sufficiently in Value from black or white, or one another. Some examples of this form of contrast would be a yellow of extreme Chroma on a black; a low value purple-blue on white ; a strong yellow on dark blue.

It is also useful to know the relative power of colours. Of course in considering the power of a colour it is impossible to think of it without a background colour and the contrast of Value and Chroma must be considered.

A strong yellow on a black field is an excellent example of maximum visibility. Although certain other factors have a bear ing on the case, this visibility may be attributed to the extreme contrast plus the power of the yellow. The power of a colour may be considered as the product of the Value times the Chroma. The magnitude of the product is a good indication of the worth of a colour from the attention or attraction standpoint. Thus, a bright, strong yellow-red would be considered as a powerful colour because of the large product resulting from its high Value and strong Chroma.

For example, in terms of the Munsell notation a yellow-red at its present extreme Chroma would be YR 7/13 with a power product of 91 (7 x 13), whereas the strongest red R 4/14 has a power product of only 56. The strongest available yellow Y 8/1 2 will have a power of 96, a little higher than the yellow-red.

The simplest use of colour is the monochrome, by which one hue alone is used in its many combinations of Value and Chroma. Some of the pleasantest colour harmonies are in the group called "neighbouring" or analogous colour schemes which utilize a series of hues in their sequence on the chromatic circle.

Complementary colour schemes offer great varieties of colour relationships from the strongest to the weakest contrast, depend ing on the Value and Chroma adjustment. When complementary colours are used together they have the effect of making each other more brilliant. This should be borne in mind in selecting the proper Value and Chroma, because if the same Value and Chroma of each colour is used, an unpleasant condition of vibration be tween the two colours will occur.

If one colour of a pair of complementaries is weakened in Chroma, the other will appear still brighter by contrast. Comple mentary pairs may be used in all the steps from low to high Value and weak to strong Chroma, depending on the purpose of a design. More than one pair of complementaries may be used in a corn position and possibilities in this group are limited only by the in genuity and taste of the designer.

In summing up, remember that while genius may work in vio lent colour combinations, those of lesser talent must play safe. Satisfactory results may be achieved if colours of low Value and weak Chroma are used for larger areas and the small areas are con trasted with colours of high Value and strong Chroma.

Two examples of the use of colour are shown in the accompany ing colour plate. The first of these shows the use of purple-blue with grey and small areas of its complementary yellow. The pur ple-blue is low in Value and moderate in Chroma as it occupies the larger area of the design. Its complementary yellow is high in Value and strong in Chroma. The grey shown in this example ap pears to be a yellow very weak in Chroma—this is the result of simultaneous contrast, the large area of purple-blue causing the grey to appear yellow (its complement) in comparison. The sec ond example shows a free use of a number of complementary hues, purples and green-yellows predominating.

The context of this article is principally a revision and condensation of "A Practical Description of the Munsell System" written by T. M. Cleland for the Strathmore Paper Company. Material has also been used from "A Color Notation" by A. H. Munsell, and "Munsell Manual of Color" by F. G. Cooper. The section on "Use of Colour" and the two sketches, by Rudolph Ruzicka are from "Three Monographs of Color" published by the Research Laboratories of International Printing Ink Corporation, a division of Interchemical Corporation. Article and colour plate arranged and designed by Arthur S. Allen.