Colour

COLOUR. In this article colour is discussed mainly from the physical point of view. Under VISION it is discussed from the physiological point of view. It is not possible to make a clear cut separation of the two aspects, and therefore the two articles supplement and overlap one another at certain points.

The Nature of Colour.—In looking round at the different ob jects surrounding him the person of normal vision recognises not only that they differ in form, but also that some are brighter than others and further that they differ in a respect which we name colour. As bodies are seen by the light proceeding from them this means that light as modified by various physical causes can produce different colour sensations. The nature of the sensa tion of colour is not a thing that can be explained to anybody who has never experienced it, although there have often been attempts to find analogies between sound and colours.

The sensation of colour can be produced by stimuli other than light, for instance by pressure on the eyeball in complete darkness. It can also be produced in darkness if the eye has previously been exposed to bright light of any colour : the so-called after images are then formed. The particular colour sensation pro duced by a light of a particular kind and strength from a coloured object also depends upon the light to which the eye has been previously exposed, and upon the colour of the objects imme diately surrounding it, phenomena which are referred to as suc cessive and simultaneous contrast. These physiological effects are dealt with under VISION as are also the various types of deficiency of colour perception. We are here dealing with the colour effects produced in a normal eye in a normal state.

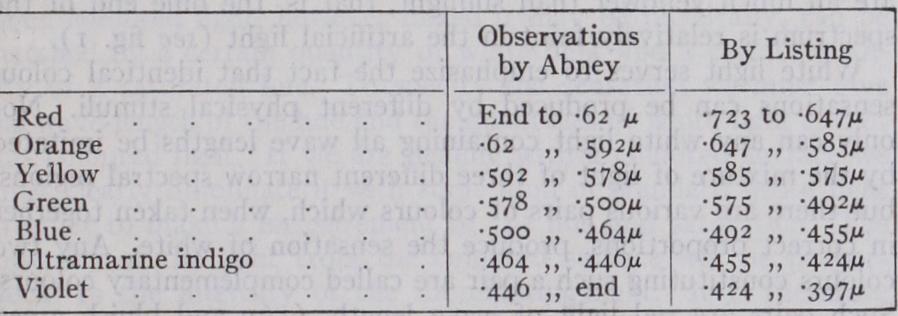

The physical side of the subject is approached most simply by considering pure spectral colours. When white light from a slit is passed through a prism and projected on a screen by a suitable arrangement of lenses, there is produced a band of light which is called a spectrum. The normal eye at once recognizes that the light at different parts of this band varies not only in brightness, but also in colour. The band is red at one end, violet at the other, and between lie a range of colours, in the order orange, yellow, green,, blue and indigo, making in all the so-called seven primary colours. Physically the spectrum represents a continuous range of wave-lengths of light, which extends beyond the limits of vision at both ends, beyond the red into the infra-red, and beyond the violet into the ultra-violet. The wave-length of the extreme visible red is something less than twice the wave-length of the extreme visible violet. (See RADIATION.) The colour sensations excited by the light blend into one another, and it is impossible to say exactly where one of the primary colours stops, and the next begins. The distinction of these colours is entirely subjective, that is, a matter of the organs of sense-perception, for physically there are no steps in the spectrum corresponding to the different colours. While by using sufficiently refined instruments the num ber of wave-lengths distinguishable by physical means can be made practically as great as we like, yet the most trained eye never sees more than seven primary colours, within which are distin guishable shades of colour. The number of shades of colour, or hues, which the eye can pick out as distinguishable within the seven primary colours is also very limited. There is some dispute as to the number, which depends to a great extent upon the method employed to isolate patches which appear monochromatic to the eye ; different experts vary in their estimate between 13o and 3o. In any case the sensations of colour divide up the spectrum in a way manufactured by the observer, and not repre sented by any physical divisions. Roughly speaking, the wave lengths corresponding to the boundaries between the primary colours found by a normal observer are given in the following table, but some people of good colour vision do not make any distinction between blue and indigo, and so naturally make a different division, while people of inferior colour vision distinguish still fewer primary colours (see VIsIoN) . The arbitrary element is still further emphasized by comparing the results of the two experienced investigators cited. The wave-lengths are given in thousandths of a millimetre, denoted by µ.

A coloured light that reaches the eye from, say, a lantern provided with coloured glasses, or from a coloured body, such as a piece of cloth, will not, in general, be a pure spectral colour, i.e., light of a given single wave-length, or of a narrow range of wave-lengths. Rather, it will consist of one or more wide continuous ranges of wave-lengths. If we want to specify the light physically we must not only be able to measure what wave lengths are present in the mixture, but also the intensity of each. When we have done this we shall have sufficient information to enable us to reproduce a coloured light which will have the same effect on any normal eye in a normal state. It must be em phasized, however, that the reverse does not hold, namely if we have a second coloured light which produces exactly the same effect as the first on a normal eye, it does not follow that it consists physically of the same wave-lengths in the same strength. For instance light of a pure spectral yellow, consisting of a nar row range of wave-lengths in the neighbourhood of -59oµ, can be matched exactly by a mixture of spectral green light and of spectral red light in suitable intensities. The eye is quite unable to decide if a colour is simple or compound. It is a fact of the greatest practical importance that any colour sensation, whatever the physical characteristics of the light that produce it, can be matched by light of three selected wave-lengths, by varying the relative intensities of these three components. This is an ex perimental fact which is quite independent of the validity of any three colour theory of vision. The question of the connection between the physical stimulus and the colour perceived is further considered in the last section of this article.

Coloured Bodies.—For the discussion of colour, white light, such as daylight, can be considered as consisting of a mixture of all wave-lengths of the visible spectrum. (The physical nature of white light is discussed in detail in LIGHT.) A body, such as a piece of cloth, illuminated by such light, appears coloured be cause it absorbs light of certain wave-lengths partially or com pletely, and throws back the remainder. Thus an ordinary blue object absorbs red, orange and yellow rays, and scatters blue together with some green, indigo and violet ; the purer the colour the smaller is the spectral region of the unabsorbed light. A yellow object absorbs the blue, indigo and violet, and generally throws back with the yellow a certain amount of green, orange and red. The colour is thus produced by absorption. When white light, say, falls on a pigment a small part is reflected unchanged at the surface as white light, but the greater part penetrates a short distance into the body and then, as a result of internal reflections and refractions due to irregularities, emerges again. modified by the loss of the rays which are most strongly absorbed. This fact can be strikingly illustrated by taking a piece of bril liantly coloured glass, and crushing it to a fine powder ; the powder will appear white. The crushing leads to the creation of a very large amount of new surface, at each of which a certain amount of surface reflection takes place, so that the light is no longer able to penetrate sufficient thickness of the substance for marked absorption to manifest itself. If the powder is now wetted with water or still better with an oil of about the same refractive index as the glass, which markedly diminishes the surface re flection, the colour is largely restored. Another illustration of the same phenomenon, given by R. W. Wood, is provided by a bead of fused borax, coloured with cobalt so deeply as to appear black. If such a bead is crushed the powder appears blue, for the diminished penetration leads to a less complete absorp tion. The white froth on a coloured liquid such as beer, is another aspect of the same phenomenon : the liquid of which the froth is composed appears brown when the light can penetrate a sufficient depth before being turned back, but the bubbles present so great a number of reflecting surfaces, that the light is unable to penetrate any depth, and the bubbles appear white.

Similarly, a transparent substance, such as a piece of coloured gelatine, held between a white light and the eye, owes its colour to the fact that it absorbs the remainder of the spectrum. Neg lect of the fact that the colours of glasses and pigments are due to absorption often leads to great confusion as to the result of mixing colours. If we mix a blue and a yellow pigment the green sensation produced is not the result of mixing blue and yellow light. The blue pigment absorbs, roughly speaking, the red, orange and yellow : the yellow pigment absorbs the blue, indigo and violet. It follows that the only colour which escapes the double ab sorption is green, which accordingly is thrown back from the mix ture. If we mix blue and yellow light, by letting a beam which has passed through a piece of ordinary yellow glass fall on a white screen which is also illuminated by the appropriate amount of light which has passed through an ordinary blue glass, the result is a white light, for yellow and blue are complementary colours. Of course if we let the light pass first through one glass and then through the other the result will be green light as with the pigments, for the light transmitted is the spectral region which escapes the double absorption. In the same way a red and blue glass, put together may stop all light and appear black, but red and blue light mixed produce a purple.

An interesting phenomenon due to absorption colour is the so-called dichromatism exhibited by certain bodies, which, viewed by transmitted light, appear one colour in thin layers, and another colour in thick layers. For instance, a thin plate of cobalt glass appears blue, a thick plate red. In such substances the fraction of the incident light absorbed in a layer of given thickness varies markedly with the wave-length. Thus if in the incident white light the green is visually more intense than the red, but the absorption coefficient for green in the substance is greater than that for red, a thin layer will appear green, a thicker layer, in which the green has been relatively reduced, yellow, and a thicker layer still, red. R. W. Wood has shown this well by dissolving the dyes "brilliant green" and "naphthalene yellow" in hot Canada balsam, and preparing a thin wedge of the substance between two glass plates; the thin edge of the wedge appears green, the thick edge red, the intermediate portion yellow. The fact that most bodies do not exhibit dichromatism means that their absorp tion coefficient is much the same for all wave-lengths.

The colour which a body exhibits must clearly depend upon the illuminating light. While there are certain exceptional substances which actually transform the light which falls on them to a different colour (see FLUORESCENCE AND PHOSPHORESCENCE) the ordinary pigment, whether natural, as in a flower, or artificial as in a dyed cloth, merely scatters back one colour of the mixed light falling upon it, and absorbs the rest; if the colour which we normally attribute to the body is not present, or is present only in reduced quantity, in the illuminating light, then the ap pearance of the body will be much modified. If a piece of white paper is placed in various coloured lights it will in each case take on the colour of the light, appearing blue in blue light, green in green light. If, on the other hand, a red poppy is placed in blue light it will appear black, for it completely absorbs blue light: in red light it will appear brilliant red, in yellow light a less brilliant yellow and in the green very dark indeed. The average blue pigment appears black in red, orange or yellow light, greenish in green light, for most blues do not completely absorb the green, and, of course, blue in blue light. The modifications in appear ance which coloured bodies undergo with change of illumination is familiar to most people from the change in appearance of fabrics in natural and artificial light. This is particularly marked with blue, in consequence of the fact that artificial light differs from daylight chiefly by relative deficiency of blue. Thus a cloth that appears blue by day will appear nearly black by artificial light, for it absorbs all colours but blue, and there is little blue present in the illuminating light. Petruschewski showed that a white surface illuminated by light from a petroleum lamp pre sented exactly the same appearance as a dark orange surface illuminated by daylight, and a bright blue surface seen by the petroleum light matched a bright brown surface seen by day light.

While most ordinary bodies, such as pigments, exhibit the ab sorption, or body colour which has just been discussed, with certain bodies the light that is reflected at the surface, without penetration, shows a marked colour. Such bodies are said to reflect selectively, and to show surface colour; they show a different colour when viewed by reflected light from that which they exhibit when viewed by transmitted light. Many of the aniline dyes show strong surface colour when prepared in thin films. The colours of the metals are of this nature; gold, for instance, which shows the well known yellow colour by reflected light, appears green by transmitted light, as can be easily shown by placing a goldleaf between two plates of glass, and looking at a white light through it. The leaf is thin enough to transmit an appreciable quantity of light.

Colours due to other physical causes also occur. Thin films, such as soap-bubbles, oil on water, and slivers of mica exhibit colours due to interference (see LIGHT). Films of uniform thick ness exhibit a uniform colour, but wedge-shaped films, such as, using the term in a general sense, the air film between a slightly convex surface and a plane surface which gives rise to Newton's rings, show complicated sequences of colours due to the removal of different spectral regions by interference at the different thicknesses. The colours of certain iridescent crystals such as are found in potassium chlorate, and opals, are due to interference from a number of approximately equidistant thin laminae. The colour of the blue sky is due to the diffraction of light by small suspended particles and the air molecules themselves; the shorter wave-lengths, i.e., those at the blue end of the spectrum, are more scattered by small particles than the larger wave lengths, so that, if light is passing through a medium containing sucb particles, an observer standing to one side sees the path of the light as blue (see LIGHT). As the blue light is not created, but merely scattered out of the white light, the beam itself will be come redder. This accounts for the red appearance of the sun at sunset, when the rays pass through a great thickness of scattered particles, and on foggy days, when the number of particles in the atmosphere is large. The colours of the rainbow are due to interference, the refraction and general theory being more com plicated than the refraction explanation given in elementary text books.

White, Black and Grey.

When we turn to the question of what precisely is meant by white light, which has been so fre quently mentioned, we are confronted by the fact that there is no precise standard. It can be roughly defined as sunlight at noon on a clear day. It is necessary to mention the time of day and the atmosphere since the relative intensities of the different colours into which sunlight can be resolved are affected by the absorption of the atmosphere, so that sunlight in the early morn ing, at noon and at late afternoon is not of precisely the same colour. The colour of sunlight will similarly be slightly different at noon on a clear day in different latitudes. Artificial lights which are usually called white differ still more among themselves and are all much yellower than sunlight, that is, the blue end of the spectrum is relatively faint in the artificial light (see fig. I).White light serves to emphasize the fact that identical colour sensations can be produced by different physical stimuli. Not only can any white light containing all wave lengths be imitated by the mixture of light of three different narrow spectral regions, but there are various pairs of colours which, when taken together in correct proportions, produce the sensation of white. Any two colours constituting such a pair are called complementary colours. Such pairs are red light of wave length .656u and bluish green light of wave length -492A; yellow light of wave length .585,u and blue light of wave length .4851.4. The most skilled eye is quite unable to analyse a white light or a coloured light into its spectral component s.

The fact that "white" artificial light differs so markedly from white daylight, by reason of its deficiency of the blue end of the spectrum, leads to coloured fabrics appearing quite a different colour in daylight and in artificial light, as has already been tioned. To obtain an artificial mination which shall make oured objects appear as they do in daylight, various types of called "daylight lamps" are made, which are extensively used by those who deal in fabrics. One such lamp is the Sheringham light lamp, illustrated matically in fig. 2, on which an ordinary electric hot wire lamp is used. The light from this lamp is thrown by a silvered reflector, which cuts off all direct light, on to a shade, the inside of which is covered with patches of colours in which green and blue predominate. These green and blue patches absorb most of the red end of the spectrum, while ing back the green and blue practically unabsorbed, and so crease the relative proportion of the blue end in the way required to give a rough imitation of daylight. A body which absorbs a large fraction of the incident light, without absorbing any one colour markedly better than another, throws back a feeble white light, and appears grey. A body which absorbs completely inci dent light of all wave-lengths throws back no light, and appears black. Black is an absence of all colour. Helmholtz says that black is a true sensation, even although it is produced by the ab sence of all light, and seeks to justify this somewhat paradoxical statement by pointing out that an object in our field of view which throws back no light appears black, but an object behind our back, which also throws no light into the eye, produces no sensation.

Classification and Measurement of Colour.

If we wish to classify the colour sensations produced by the light from coloured bodies the immediate problem is not to analyse the light physi cally into its different wave-lengths, each of a given intensity, but rather to find the simplest way in which the same colour sensa tion can be produced. It is a fact of experience that, apart from intensity, i.e., the brightness of the colour, any colour can be matched by a spectral colour to which a proportion of white light has been added. Pure spectral colours, without admixture of white light, are said to be saturated, and, in proportion as white light is added, become less and less saturated. The spectral colour is usually referred to as a hue, the term colour being reserved for the general sensation. The statement that any colour can be matched by a spectral hue to which white has been added requires qualification, for the purple sensation cannot be so matched. A saturated purple is itself produced by mixing light from the violet and red ends of the spectrum, and such a purple must be added to the spectral hues to complete the description. The purple hue, which is compounded of the ends of the spectrum, can be regarded as affording a transition from one end to the other, so that the hues can be arranged in a circle, with purple between the red and violet, forming a bridge from one to the other. We may, then, taking the spectral colours and purple as saturated hues, say that colour sensations can differ in three respects only : hue, saturation and intensity. This classification was introduced by Helmholtz. Expressed somewhat differently, the sensation produced by any given coloured light, however mixed it may be physically, can be matched by a certain quantity of white light and a certain quan tity of a saturated hue. To specify the sensation we must give the wave-length of the hue and the quantities of white light and of this coloured light. If we are dealing with a coloured surface we must clearly illuminate it with some kind of standard white light in order to make a measurement of the hue and saturation. The intensity of the light from the coloured surface will be propor tional to the intensity of the illuminating light. It is therefore reasonable to take, as a measure of the intensity of the colour of the body, the ratio of the brightness of the light proceeding from the body to the brightness of the light from a perfectly white surface similarly illuminated. The term brilliance is often used, especially in America, to denote this ratio.Newton arranged the saturated hues round the circumference of a circle as shown in fig. 3, and placed at the middle of the circle white. Any line joining the centre W to a point P of the circumference then represents the transition from the saturated hue represented by P to white light, the degree of saturation lessening to zero as we approach the centre. Newton also gave a rule by which the result of mixing colours could be ob tained from his figure, certain weights being attributed to each spectral hue, and the cen tre of gravity found. This two dim ensi onal figure has been variously modified, a colour triangle being a more usual method of representation (see Vision). If, as Lambert did, we use three dimensions and let lines normal to the surface represent intensities, diminishing as we go upwards, we can represent any colour sensation. We have a pyramid of colour, the point of which will represent black. There have been many modifications of this three dimensional representation of colour sensation, de signed to get over certain difficulties which arise in respect of the laminating values of the colour sensations. One of the most recent is that of Munsell, in which the three co-ordinates are :—the height of the point from the horizontal plane, representing the intensity, or brilliance; the distance from a vertical axis, repre senting the saturation; and the angle from a vertical plane, repre senting the hue.

A method of colour classification much adopted, on account of its simplicity of use, among those practically concerned with col our, such as manufacturers of paints and printing inks, is some form of colour atlas or colour chart, in which patches of various colours are arranged on some system. The Munsell colour tree to which reference has just been made is used to effect the classifi cation in such a chart, known as the Munsell colour atlas, issued by the Munsell Colour Company, in America. Ostwald in 1917 brought out a very elaborate colour atlas, with about 3,00o colour specimens. He used a special classification—hue, white-content, black-content—in place of Helmholtz's hue, saturation and inten sity. The Societe des Chrysanthemistes issues a colour chart with colour names in four languages. A necessity of any such colour chart, is of course that all copies shall conform accurately and that the colours shall not fade.

A large number of instruments have been devised for colour measurement. For scientific investigations of colour perceptions much use has been made of the colour-patch type of apparatus, in which lights of two or more different wave lengths, isolated from a spectrum by slits, are brought into coincidence as super imposed patches on a white diffusing screen. The intensities of the separate colours can be varied so as to produce all possible shades. This apparatus exists in various forms. For technical work instruments are now being constructed in which, instead of a spectral hue, light which has passed through an arbitrary colour filter is being used. The three beams of light, one of which has passed through a red filter, the second through a green filter and the third through a blue filter, are brought into superposition on a screen. Each beam can be varied in intensity. One of the best forms of such apparatus is due to Guild. In Guild's trichro matic colorimeter the light enters by three sector-shaped win dows, provided respectively with red, blue and green filters. By the mechanism of a revolving prism the field is illuminated by light from the three windows in rapid succession, When the speed of alternation is high enough the sensations blend and the mixed colour is perceived. Still another type of instrument, called the tintometer, depends upon passing the light successively through three filters of different colour, each of which subtracts some thing from the original white light. Although only three colours are chosen each must be represented by a series of various depths of colour, so that some 4 7o glasses are necessary in a complete matching set. The match is then given in terms of the depth of colour of each of the three filters which, placed one behind the other, transmit the given light.

A different type of apparatus is the spectrophotometer, by means of which the physical constitution of a coloured light may be actually measured. The light is resolved into a spectrum, and the intensity of each wave-length present is measured separately. This measurement is usually effected by the help of a standard source of white light, the intensity of the transmitted hue being controlled by polarizing prisms of one type or another. If two such prisms are used, one as polarizes and the other as analyser, the intensity of the light transmitted can be controlled by rotat ing the analyser, the angular position of which gives an exact measure of the percentage of light cut off (see LIGHT) . The Nutting spectrophotometer and the Konig-Martins spectropho tometer are two well-known instruments which make use of this principle (see PHOTOMETRY). Such instruments are largely used for measuring the light transmitted by colour filters, coloured glasses, dyes and so on.

A third type of instrument is the colorimeter of the Nutting pattern, which matches any given coloured light by manufacturing a light of given hue, saturation and intensity. A spectral hue is separated out from a spectrum by means of an adjustable slit, and a given quantity of white light is added from a separate source. This gives adjustable hue and saturation. The intensity is varied by altering the width of the slits, or else by other means commonly used in physical instruments, such as rotating sectors with con trollable gaps or polarizing prisms.