Combinatorial Analysis

COMBINATORIAL ANALYSIS. Combinatory analysis is a branch of mathematics dealing with various elementary topics in number theory, algebra, and tactical geometry and exten sive developments therefrom. Historically this title includes the beginnings of topics now rightly assigned to number theory, Diophantine analysis, the theory of probability, determinants, group theory, Analysis Situs, and the theory of aggregates. Even the formulas of the theory of partitions may be included in Number Theory, and symmetric functions in the Theory of Forms.

Many of the traditional problems which involve at most the investigation at any stage of a discrete number of possibilities, usually fall under the general designation of combinatorial problems. Among the best developed might be said to be the subjects of triple-systems (established on a firm basis by the work of J. Steiner, 1852, and E. H. Moore, 1893); Magic squares, Latin squares, the map colouring or four-colour problem, the eight queens problem, the Game of Nim (C. L. Bouton, Annals of Mathematics, 2nd ser. vol. i., 19o2), unicursal or maze prob lems, theory of knots, tesselation or parquetry, decimation problems and the Problem of the Virgins. Such subjects as cryptograms, bridge problems, and chess problems, while deeply studied, continue largely unmathematical.

A hint as to the historical sequence (mentioning only conspic uous early investigators) in the development of the elementary fundamental subjects in this field may be afforded by the fol lowing bare list: (I) Figurate numbers (triangular, square, and polygonal numbers generally, pyramidal, cubic, prismoidal numbers, etc.)-earliest Pythagoreans, Nicomachus (c. A.D.), Diopha,ntus (c. 25o A.D.), Fermat (i621), Lagrange and Euler (177o), Gauss (i8oi); (2) the binomial coefficients-re puted Chinese writings of i4th century, Michael Stifel (1544), Briggs (162o), Pascal (1665), Leibniz (1666), Newton (1676), Wallis (1685), J. Bernoulli (1713); (3) permutations, combina tions, probability-J. Bernoulli (1713); (4) symmetric functions -Girard (1629), De Moivre (1698), Newton (r7o7), Waring (1762), Lagrange (177o); (5) determinants-Leibniz (169o), Cramer (1750), Lagrange (1773), Gauss (I8oi), Cauchy (1815); (6) the application of generating functions to problems in parti tions-Euler (177o), Ferrers (1853), Sylvester (1882).

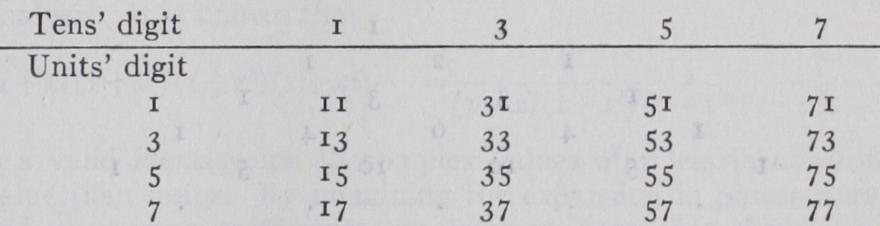

Illustrative Examples.-Consider

the following simple prob lem in permutations (one of the two traditional uses of the term, here meaning "arrangement"): What numbers of two figures each (in the usual decadic notation) can be formed with the digits, 1, 3, 5, 7? To make the problem precise it must be stated whether repeated use of a digit in the representation of a single number will be permitted. We may obviously form a table as follows: The numbers are all distinct and are clearly 42 = 16 altogether, of which four, those in the "principal diagonal" have repeated digits, leaving 4.3 = 12 numbers with digits distinct.

Analogous problems in combinations are distinguished from problems in permutations in that the arrangement of the ele ments is now regarded as without significance, attention being devoted merely to which elements are selected. For example: In how many ways can two numbers whose sum is even be se lected from among the numbers, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. 6, 8? We note first that both summands must be even or both odd to have an even number as their sum, and that the order of their choice is immaterial. Again the problem must be made precise by stipu lating whether or not two equal summands are to be accepted. Suppose distinct summands only are desired. For odd summands, there are two pairs using the number 1, namely (I, 3), (1, 5) and one more using the number 3, namely (3, 5). There are similarly three pairs using the number 2, namely (2, 4), (2, 6), (2, 8), two new pairs using 4 but r,ot 2, namely (4, 6) and (4, 8), and one remaining pair (6, 8). The total number of pairs is therefore (2+0+(34-2-FI)= 9.

Two Numerical Functions.-Before making a systematic study of such problems, it is desirable to introduce two numerical functions. The first of these logically, although not historically, is the factorial function n! or In, defined, for n>i, as the con tinued product of the natural numbers up to and including n. Thus n! =1.2 . (n-i).n. For each positive integer n>t, we have the recursion relation (n+ I) ! = (n+i)(n!). In conformity with this relation we naturally define 1! as and o! as 1, and regard n! for negative integers as not finite. The first few values of n! are given by o! = r, ! = 1, 2! =2, 3! =6, 4! =24, 5! =I20, 6! = 72o, 7! = 5,04o, 8! =40,32o, 9! =362,880. The value of n! increases, with increasing n, with extraordinary rapidity. The remarkable size of the answers to certain combinatorial prob lems due to this fact has interested and astonished generations of schoolboys. For large values of 71 an approximation of n! is afforded by Stirling's asymptotic formula (173o), which, to give only the leading term, approximates n! by ()"V(2rn) where e is the "Naperian base", 2.71828 . The factorial function (n I)! may be regarded as exhibiting the integral values only of the celebrated gamma function (of Euler), F(n), while F(x) is defined for complex numbers generally. It is of interest that P(Z) = %17r, and more generally r(x) F (i -x) = 7r/sin (7r x) . Further study of this function leads through the very heart of modern analysis to difference equations, complex functions, definite integrals, contour integration, asymptotic series, etc. In number theory n !+ i may be used in Euclid's proof that the number of primes is infinite, and occurs also in Wilson's theorem.

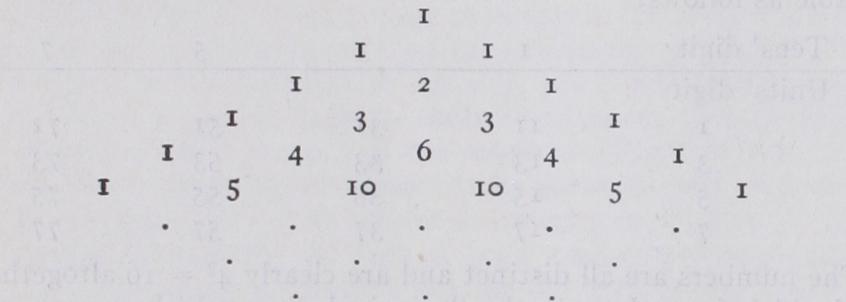

The next function needed is the binomial coefficient (), a numerical function of two independent integers, n, k, and definable in terms of factorials by (k) = n ! / [(n k) ! k !], (Newton, 1676), although much older than either factorials or the binomial theorem. The values of (k) may be conveniently exhibited by the so-called Pascal's arithmetical triangle (Apianus, 1527; Michael Stifel, 1544; Blaise Pascal, 1665; and apparently by Chu Shi-kie, 1303), where the (k + i)st element counting whether from left to right or from right to left in the (n+ i)st horizontal row (counting from the top) is The triangle extends downward indefinitely. It starts as follows: A table of its values up to n, k = 5o, is given by J. W. L. Glaisher (Messenger of Mathematics, 47, . The law of formation of a horizontal row from the elements of the row above may be expressed concisely by the conditions = (n) = n These properties of alone, are used in establishing by complete induction the binomial theorem: for positive integral exponents n. In the theory of combinations (k) is sometimes denoted by Ck, and may then be called "the k-combination of n" or "the number of combinations of n dis tinct things taken k at a time without repetitions." Many important and surprising relations hold among these binomial coefficients for which reference may be made to Hagen, Synopsis der hoheren Mathematik (vol. i, 1891, p. 64 sqq., or Netto, chap. xiii.).

Two Fundamental Problems.

Perhaps the simplest and most fundamental general problem in the subject of permuta tions may be stated in traditional form as follows: To determine a systematic method of securing once and only once each possible arrangement (or "permutation") of k things selected from among n given distinct things; (a) when repetitions are allowed, (b) when the things in each arrangement of k things are distinct. Also to determine the number of such arrangements. In an "arrange ment" as here used, the only feature considered is the ordinal count of the distinct objects, i.e., as to which is first, which is second, which is third, and so forth. When repetitions are permitted, one may select the first object for our arrangement in any one of n ways, since one may select any one of the given objects of the set to be the first of the arrangement. This having been done one can again select any one of the n as the second, and so forth, obtaining possible arrangements of exactly k things from among n permutations permitted. For repetitions not permitted, the first is selected in any one of n ways, the second arbitrarily from among the (n 1) left avail able. This makes n(n i) ways of selecting this first ordered pair. The third may be chosen as any one of the n 2 remaining things, giving n(n 1) (n 2) distinct possible ordered triads, and so forth. The number of distinct arrangements of k distinct elements selected from among n given distinct elements is therefore n (n i) (n k -}-1) = n !/(n k) ! , denoted sometimes by Pk , "the k-permutations of n," or "the number of arrange ments (or permutations) of n distinct things taken k at a time without repetitions." The corresponding problem in combinations is in some ways more fundamental. It may be stated as follows: To determine a systematic method of securing once and only once each possible combination of k things selected from among n given distinct things: (a) when repetitions are allowed, (b) when the things in each com bination of k things are distinct. Also to determine the number of such combinations. By a combination is meant a collection without regard to the sequence or order among the elements. Instead of starting afresh as may be done, let us assume that the permutation problem has been solved and a table is before us giving all distinct arrangements of k things selected from among the given n. We may treat to some extent simultaneously cases (a) and (b). The following procedure is analogous to the use of the Sieve of Eratosthenes (c. 23o B.c.) in the theory of prime numbers. Establish in any arbitrary manner a sequence among the "arrangements" appearing in the table. Take the first arrangement. Note what k things are there contained. Go through the entire table crossing out all other arrangements comprising these same k things and constituting merely rear rangements of this first accepted arrangement. Proceed to the next arrangement that has not yet been crossed out and repeat the process. This is clearly a procedure that never requires one to turn back and re-examine or cross out any arrangement once accepted. All the arrangements that finally remain will con stitute also distinct combinations. In case (b) when no arrange ment contains repeated elements, the number of distinct ar rangements which constitute the same combination is clearly = k! , since it is possible to arrange a given set of k things in exactly k! ways and each of these possible ways must appear once and only once in the table. The entire collection of = n !/(n k) ! distinct arrangements contains therefore each combination exactly k! times, so that the number of distinct combinations is (n !An (n k) !/k ! or CO Before taking up the count in case (a), the case of combina tions with repeated elements, it is convenient to note certain combinatorial relations in a set of integers arranged in increas ing order. Consider a set, s, of k distinct numbers selected from among the first n+k 1 natural numbers, and let this set be arranged in increasing order. It is to be noted that the hth num ber in this set, s, (h = 1, 2, , k) cannot be less than h nor more than For its smallest value would occur when the first h numbers of the set are consecutive, giving the value h, and its largest value would occur when the last k h+ 1 numbers are consecutive, giving the value n+h 1. If from the hth number of the set we subtract h 1, (h = 1, 2, , k), the consequent derived set, s', will be arranged in non-decreas ing order, and no one of its elements is greater than n. This derived set may contain repeated elements. Two distinct given sets, s, result in two distinct derived sets, s', and conversely tinct derived sets, s', correspond to distinct given ordered sets, s. We may state the following important theorem in tions. For each set, s, of k distinct natural numbers arranged in order of increasing magnitude selected from the first n+k 1 natural numbers, there is a uniquely determined set s' of k natural numbers arranged in order of magnitude selected with repetitions allowed, from the first n natural numbers, and conversely. turning now to case (a) for combinations, we may imagine our original set of n distinct things numbered ordinally from ist to nth. In each combination of k things selected from this set, the k things retain their ordinal designation, so that each combination may have its k elements arranged ordinally in a unique manner except for repeated elements, among which order is regarded as immaterial. By applying the theorem stated above, we see that the theory of combinations allowing tions as considered in case (a) may be replaced by the theory of combinations of k elements selected from an initial set of elements, no repetition being allowed. Thus the number of combinations permitting repetition in case (a) is I k ) Partitions.A subject at first sight independent of permu tations but in fact almost identical with it is that of partitions, one theorem in which subject has been mentioned above. This topic is but a phase of the general subject of distributions, being the theory of combinations of summands having a given sum. For compactness in display, it is convenient to formulate the typical problem as follows: In how many ways can the number m+n be represented as the sum of exactly n distinct positive integers? Thus for n = 4, m= 2, we have two ways, and for n= 2, we have 6 = 5+I =4+2 =3+3, three ways. The following table was given by Euler who studied the recursion relations among the values.

If this partition function be denoted by P(n, m), we haw, the relations of Euler: P(I, m) = P(n, o) = P(n, I) = I, P(n, m) = o, (m

From the simplest tactical considerations (Ferrers, 1853) of the horizontal rows and vertical columns of a point diagram ("lattice diagram" or "graph") such as the following, one may infer an important general theorem. Here we have twenty points arranged in horizontal rows containing respectively; 5, 4, 4, 3, 2, 2, points and also in vertical columns containing re spectively 6, 6, 4, 3, I, points: tions we have the Theorem of Reciprocity (Sylvester, 1882) : Every partition of n into k positive summands of which the greatest is equal to h, determines a reciprocal partition of n into h positive summands of which the greatest is equal to k. As immediate corollaries one has: The number of partitions of n into le parts is equal to the number of partitions of n into parts of which the largest is k; and, The number of partitions of n into not more than k parts is equal to the number of partitions of n with no part greater than k.

Another Problem in Permutations.

Another typical gen eral problem in the domain of permutations and combinations is the following: Given a partition of n, say n = m1+m2+

to determine the number of distinct possible arrangements using all of n given things, each once only, of which

are alike (say of type I),

are alike, but of another type (say type 2), and so forth, there being in all, h distinct types. Since rearrangements within each type are freely possible, among the total n! possible arrangements of elements, one has

arrange ments differing only with respect to interchanges among ele ments of type 1. These are independent of rearrangements within type 2, and so forth, giving

arrange ments distinct with respect to type. This number is called a multinomial coefficient on account of its being the coefficient of xml x2 2 xrh in the expansion of

in powers of the separate arguments. This is the germ of two lines of in vestigation, the study of the powerful method of generating functions in which the coefficients of the several terms of a power series are interpreted as numerical functions (used throughout MacMahon's treatise), and the study of divisibility of factorials by products of factorials, since the multinomial coefficient is necessarily an integer. (See Dickson, History of Theory of Numbers, vol. i., ch. ix.) As to generating functions, lack of space and the complexity of the subject require us to dismiss briefly this fundamental tool for research in combinatorial analysis. It is known that

= (1

(I

(I

(1

is a valid identity for all complex values of x less in absolute value than unity. By imagining the expansion in power series and comparing coefficients, we infer at once that the number of representations of n as a sum of odd integers allowing repeti tions is equal to the number of representations of n as a sum of distinct integers (allowing both odd and even numbers) . De Morgan's theorem illustrating the simplest case of Sylvester's denumerants, proved by use of generating functions, states that the number of representations of n as a sum of the numbers I, 2, 3, allowing repetitions is equal to the integer lying nearest to

Sets and Subsets.The theory of combinations with distinct elements is identical with the theory of finite aggregates or finite sets. Many of the concepts apply equally to all well-defined sets whether finite or infinite. There are many grave philosoph ical difficulties associated with the general definition of set (see Whitehead and Russell, Principia Mathematica, vol., i., ch. ii., particularly p. 63 sqq.), but this concept lies at the basis of modern analysis. (Hobson, Functions of a Real Variable, 2nd ed. I, p. 1-2.) One may at least say that a set is a collection comprising distinct objects of any sort, called elements of the set, such that it may be definitely ascertained whether any arbitrarily assigned object is or is not an element of the set. If A and B are sets, A is called a subset of B (and B a superset of A) if and only if each element of A is an element of B. Thus A is a subset and superset of itself. It is convenient to introduce a unique null-set with no elements which is a subset of every set. Any subset of A which is neither A itself, nor the null-set is a proper subset of A. The elements common to two sets A and B constitute the section or logical product of A and B. The set each element of which is in at least one of the sets A, B, is the spread or logical sum of A and B. Given three sets A, B, C, the sets A and B are said to be supplementary in C, if and only if A and B have no common element, and C is their spread. In this case only is subtraction possible. We write then B = C - A, and A=C-B. This notion may be used to demonstrate the theorem, If n > k > h, the number of combinations of n distinct things taken k at a time (without repetitions), which include h specified elements, is equal to the number of combinations of these same n things taken n - k at a time (without repetitions) which exclude each of these h specified things. In particular for h=o, (k) = (n n

. If a set has a finite number, n, of elements, the total number of subsets is

since each

in turn may independently be included or excluded. Hence ()+ (I) + (':)+ + (fl) =

as follows also by putting a= x= I in the binomial expansion.

Uniform Correspondences.

If a correspondence is estab lished from a set A to a set B such that for each element of A there is one and only one corresponding element of B, the corre spondence is uniform (or "one-to-one" in the broad sense) from A to B, and determines a single-valued (or uniform) function "on A to B." This is the sense in which "function" is now used throughout mathematics, after successive extensions through centuries. If a correspondence is one-to-one reciprocally from A to B so as to establish an actual pairing off of elements of A against elements of B, it is biuniform (or "one-to-one" in the narrow sense of "one-to-one reciprocally") . The corre spondence then has a unique biuniform inverse correspondence from B to A, which determines the same tallying or pairing off. Two sets between which there can exist a biuniform corre spondence are said to be equivalent or to have the same car dinal number. (See NUMBER, or Cantor, Theory of Transfinite Numbers [trans.], 1915.) When two finite sets A and B have the same cardinal number n, there exist n! distinct biuniform correspondences from A to B. It is sometimes convenient to select one of these correspondences as a principal correspond ence and by means of it establish a corresponding notation for the two sets. When A and B coincide, this principal corre spondence is chosen as merely the identical correspondence whereby each element corresponds to itself. A biuniform correspondence within a single set may be called a substitu tion (or "permutation" in the more fundamental sense). The simplest type of substitution is a circular or cyclic substitution, permuted elements all following in a single cycle. Each ele ment of the cycle may be carried into any other element of the cycle by repeating the given correspondence or its inverse sufficiently often. (Where the cycle contains but a finite num ber of elements, the inverse is itself obtained by repeating the direct correspondence a certain number of times.) The simplest cyclic substitution after the identity is a transposition, by which a single pair of elements is interchanged, and every other element left unaltered. Each substitution in a finite set may be expressed (in an infinite number of ways) as the result of a finite number of transpositions, but more interestingly, as the result of a finite number of component cyclic substitutions each of which leaves .unaltered every element permuted (not left invariant) by any other of the component cyclic substitutions. Thus each substi tution breaks up the given finite set of elements into uniquely determined cycles. A substitution within a finite set is said to be even or odd according as the number of cycles each with an even number of elements is even or odd. In this connection we have the important theorem : A substitution in a finite set which is expressible as the result of an even number of transposi tions is even, and one expressible as the result of an odd number of transpositions is odd. Each substitution is either even or odd, but never both even and odd.Any study of substitutions leads to the consideration of groups of substitutions. From this fundamental point of view the theory of permutations (in the sense of arrangements) so far as the case of distinct elements is concerned is a phase of the study of substitutions among elements of subsets of a given set.

Matrices and Determinants.

Given two sets not neces sarily finite), A and B. Let a denote a variable element of A, and b a variable element of B. A set C is called a direct product of A and B (to be distinguished from "logical product") if there is a biuniform correspondence between the elements of C and the ordered pairs (a, b). If the elements of C are indepen dent algebraic variables, then C is called a general matrix on (A, B). The variable a is said to determine the (horizontal) row and b the (vertical) column of the matrix. When A and B have the same cardinal number, the matrix is square. If a principal correspondence is chosen between A and B, the nota tion acquires a meaning. The set of all these variables with repeated subscripts are said to constitute the principal diagonal of the square matrix. There need be no preassigned arrange ment among the elements of A. Thus, if A consists of the three symbols -I-, X, o, then there is a general square matrix of nine independent variables, say w+x, w+o, wx+, wxx, wxo, wo+, which can be written in any order but of which w++, wxx and form the elements of the principal diagonal, and for example, wxo, wx+, are in the same row (in some order). By a determinantal product of the elements of a general square matrix of order n, i.e., with n rows and n columns, is meant a product H of elements "one from each row and each column," that is, a product of n elements where the first subscripts, a, take on each value in A once and only once, and the second subscripts, b, take on each value once and only once. For ex ample, the following are determinantal products of the matrix given above, wx+ wox, woo wx+ w+x, wxx woo w++, but such a product as w+x is not a determinantal product since among first subscripts -I- appears twice and o not at all. The product of the elements of the principal diagonal is always a determinantal product (the principal determinantal product). For a finite square matrix of order ii, there are ii! such deter minantal products. (Only 2n+ 2 are independent [Polya, Arch. d. Math. u. Phys. [3] 24 [ 1916], PP. Now each product determines a biuniform correspondence from A to B and hence among the set of symbols used in common by the two sets. This correspondence is that by which the value of a appearing as first subscript in any factor corresponds to the value of b which is the second subscript of this same factor. Thus for a square matrix of finite order, each of the n! deter minantal products determines definitely either an even or an odd substitution. The principal determinantal product deter mines the identical substitution which is even. For n> 1, there are the same number, n!/2, of even as of odd substitutions. To each of the n! determinantal products a sign is attached, +, if the substitution it defines is even, - , if the substitution is odd. The algebraic sum of all these signed products is defined as the determinant of the general matrix. (See DETERMINANTS.) For a matrix of order nine, the product x27x18x49x66x73x81x35x94x52 determines the cycles (2735) (i8) (49) (6), with three of an even number of elements. This product is given the minus sign. For the traditional method of determining the sign of a term by counting "permanences" and "inversions," see Scott and Matthews, Theory of Determinants (2nd ed., 1904, p. Symmetric Functions.The application of substitution groups to algebra finds a rich development in the Galois Theory of Equations. The simplest topic in this connection, essentially preliminary and incidental to the latter subject, is the theory of symmetric functions, fundamentally equivalent to much of the theory of distributions. A symmetric rational integral function of n independent variables a, 0, , v, may be expressed as a sum of terms, each of the form yin where are non-negative integers, where the summation sign, covers all terms obtainable by transpositions among the variables. The sum all has a unique term for which This is called the leader, and the whole sum is called a monomial sum. A monomial sum is completely identified by the specification, of its leader, where the final set of zeros, if any, may be omitted, and where suc cessive equal indices such as i a = i = = a+h_1 may be con densed by writing i a . The most important monomial sums are the n elementary symmetric functions (1"9,(m= 1, 2, , n) and the infinite sequences of power-sums, sn, (m), (m = r, 2, ), S = n. It is often convenient to define the symbol (rm) for m> n as identically zero, thereby enabling many recursion relations to hold universally. Another important fundamental system of symmetric functions is the infinite sequence of homo geneous product-sums denoted by h, where for example, = (4) ± (30+ (22) ± (212) + (0), and hm generally is the sum of all monomial sums whose specifications are partitions of m. A system of great interest, relatively little studied in this con nection (Thiele, 1880 is the system comprising in addition to to= , and ti = (r)/n, the algebraic semi-invariants, 4 (Cayley, 1886) definable by the implicit recursion relation but for m = r, 2, = t,(a,(3, , v) + c. For the relations among these involved in Newton's Identities, Waring's Formulae and the proofs, and generalizations, the reader is referred to treatises on Algebra. The entire subject of symmetric functions acquires new significance when studied from the point of view of alge braic invariants. The differential operators of invariant theory are illustrated for example by the Hammond operator, D , used to determine explicit coefficients in certain expansions. (See MacMahon.) The process transvection by which concomitants of a system of forms are obtained suggests the use of multi linear symmetric functions of m systems, a subject not yet devel oped. The set of independent variables. (a, 0, , v) may be come infinite in number or even continuously infinite as in the theory of integral equations. Or again all explicit mention of them may be suppressed as in certain algebraic studies, and a general theory including that of symmetric functions be de veloped, but applicable to much wider domains. Determinants in non-commutative domains have been investigated (see LINE AR ALGEBRAS) , and this suggests further problems in this line also.