Combustion

COMBUSTION. This term implies the process of burning and in the popular mind is generally associated with the produc tion of flame (q.v.). So far as terrestrial conditions are con cerned, it is due to the combination of a combustible substance with oxygen and the consequent evolution of heat. The condition of flame is due to the oxidation of gases or vapours at a very rapid rate so that high temperatures are attained, the molecules con cerned thereby becoming highly radiant. Scientifically, the term has a broader meaning and is extended to other oxidations. At atmospheric temperature oxidation of a combustible material generally occurs, if at all, only very slowly, and usually with little outward manifestation. When, however, the temperature is raised, as for example by the application of some external source of heat, the process becomes greatly accelerated, and if the "ignition point" be reached, heat will be developed at a rate greater than that at which it can be dissipated and flame will ensue. Thus, when a lighted match is applied to coal-gas issuing from a jet, the temperature is so raised that self-propellant combination is estab lished between the gas and the oxygen of the air with which it intermingles, flame then appears and is maintained at the jet. Similarly, when coal is heaped on a fire, its volatile constituents liberated by heat mix with the surrounding air and after ignition give rise to flame; the residual coke, consisting largely of carbon, becomes incandescent, its primary oxidation proceeding without flame.

The explanation of the nature of fire or flame was sought in very early times. At first fire was thought to be an element, but as far back as the fourth century B.C. it was demonstrated that air plays an important part in the phenomenon. During the middle ages, however, the notion of an "element of fire" universally pre vailed until Francis Bacon classed it among his "phantoms of the market place" as one of those "fictions which spring from vain and false theories" (Novum Organum). The first important experimental study of combustion commenced with the Oxford School of Chemistry about i 66o under the leadership of Robert Boyle. With the assistance of his pupil Robert Hooke, he had contrived his "Machina Boyleana," a forerunner of the modern air-pump, and by its aid proved that neither charcoal nor sulphur burns when strongly heated in vessels exhausted of air, although each inflames as soon as air is readmitted. Having found that a mixture of either substance with nitre catches fire even when heated in a vacuum, Boyle concluded that combustion depends upon the action of something common to both air and nitre. He concluded further that, in the calcination of metals a ponderable "fire-stuff" is taken up, thus accounting for the gain in weight already observed by the French physician, Jean Rey, in 163o. Robert Hooke said (picrographia, 1665) ". . . that shining transient body which we call Flame, is nothing else but a mixture of Air, and volatil sulphureous parts of dissoluble or combustible bodies, which are acting upon each other whilst they ascend. . . ." It was, however, John Mayow, another of Boyle's pupils, who in his Tractatus Quinque Medico-Physici (1674) expounded views nearest to those held to-day. In common with Hooke, Mayow regarded heat and light as originating in the motions of particles. By making the now familiar experiment of burning a candle or other substance in a bell jar of air enclosed over water, he ob served that the air is diminished in bulk by combustion and that when the flame expires the residual air is inactive and will not support combustion. Also he observed that the respiration of animals in an enclosed space had the same effect, and concluded that respiration and combustion were analogous processes. He therefore postulated the existence of two kinds of particles: (a) inflammable particles which exist in all combustible sub stances, and (b) nitro-aerial particles which, originating in the sun, become linked to normal aerial particles (which per se are inert) in the upper atmosphere. These particles (a and b) are mutually so hostile that when suitably brought together they enter into sharp conflict, whereby they are thrown into violent motion the outcome of which is the appearance of fire. Such a view differs from that propounded by A. L. Lavoisier a century later and now held, in that (i.) it did not recognize that common air is a mixture of two physically similar but chemically distinct gases, and (ii.) it regarded combustion only as the interplay and not as the actual combining of two opposite kinds of particles. But for his early death in 1679 Mayow might have discovered the gas now called oxygen.

At the beginning of the i 8th century, another view of combus tion known as the "phlogiston" theory, originally propounded by J. J. Becker (1635-1681), was developed and promulgated by G. E. Stahl, and soon became universally accepted. According to this theory, all combustible bodies contain at least two "prin ciples"--one of "combustibility" called phlogiston (from the Greek IOros, burnt) which escapes during combustion, and the other of "incombustibility" which remains behind as the ash. More easily combustible substances, e.g., charcoal, were supposed to consist so largely of phlogiston that after its escape during combustion little or no visible residue remains. The inherent defect of the theory was that it did not account for the fact that the products of combustion are invariably heavier than the original substance. This was overcome by ascribing to phlogiston a nega tive weight. The phlogiston theory dominated chemistry during the greater part of the i8th century but it did not long survive the discovery of oxygen by K. W. Scheele and by J. Priestley; for Lavoisier was able to prove that this gas is really the active constituent of air, and in 1783, after Henry Cavendish's dis covery of the composition of water, he correctly interpreted its compound nature as an oxide of hydrogen. In his Reflections sur le Plzlogistique he denied the existence of phlogiston and pro pounded his new oxygen theory of combustion. His main con tentions were, (i) inflammable substances will burn only in oxygen or where oxygen is present; (2) oxygen is consumed in combustion and, uniting with the substance burnt, causes an increase in weight and a corresponding decrease in the weight of the air used.

Spontaneous Combustion.

In certain circumstances ignition may occur without the application of any external source of heat. Thus, when heaps of finely divided coal or of cotton waste soaked in oil are kept in badly ventilated places, oxidation, proceeding slowly at first, may cause heat to accumulate until ultimately the temperature is raised to the "ignition point," when inflamma tion occurs. The spontaneous firing of hay-ricks is the result of similar causes.

Slow and Catalytic Combustion.

It has already been mentioned that oxidation of a combustible material can occur at temperatures below those at which flame is developed. Thus, Davy in 1817 discovered that when mixtures of hydrogen and oxygen are passed through a tube heated at temperatures between 36o° and 500° C • they combine to form water "without any violence and without light." W. A. Bone and his collaborators have found that mixtures of certain gaseous hydrocarbons with oxygen are very reactive at woo° C and In some cases even nt a 5o° C. The rate of such combination is always accelerated by contact of the reacting gases with some foreign material or surface, a phenomenon of the greatest importance in chemistry and known as "catalytic" or "surface" combustion. As a result of these and other researches, it is necessary to distinguish be tween two possible conditions under which gaseous combustion may occur, viz., (i.) homogeneously, i.e., uniformly throughout the system as a whole, (a) at temperatures below the ignition point, slowly and without flame, and (b) at temperatures above the ignition point, rapidly and with flame; and (ii.) hetero geneously, i.e., in layers in direct contact with a hot surface. Incandescent Surface Combustion.—Davy also set out to enquire whether, seeing that the temperatures of flame far exceed those at which solids become incandescent, a body can be main tained in an incandescent state by combination of the gases at its surface without actual flame. He discovered that if a heated platinum wire be plunged into a mixture of coal-gas with air rendered non-explosive by excess of the combustible, the wire immediately becomes red hot and continues so until nearly the whole of the oxygen has disappeared. In i 906 W. A. Bone was able to effect a flameless incandescent surface combustion by burn ing explosive gas–air mixtures in contact with surfaces of ordinary refractory material, which were thereby maintained in a continu ous incandescence without flame; and in conjunction with C. D. McCourt he applied this discovery to various domestic and in dustrial heating operations, including steam raising, etc. The advantages of such a system are, (i.) the combustion is greatly accelerated by the incandescent surface, (ii.) the combustion is perfect with a minimum excess of air, (iii.) the attainment of very high temperature is possible and (iv.) owing to the large amount of radiant energy developed, transmission of heat from the seat of combustion to the object to be heated is very rapid.Lastly, it should be mentioned that combustion is not neces sarily controlled by simple thermal factors but may be profoundly influenced by the electrically charged condition (degree of ioniza tion) of the reactants. Such is probably the case in the ignition of explosive mixtures by electric discharges and also in catalytic combustion.

Gaseous Explosions.

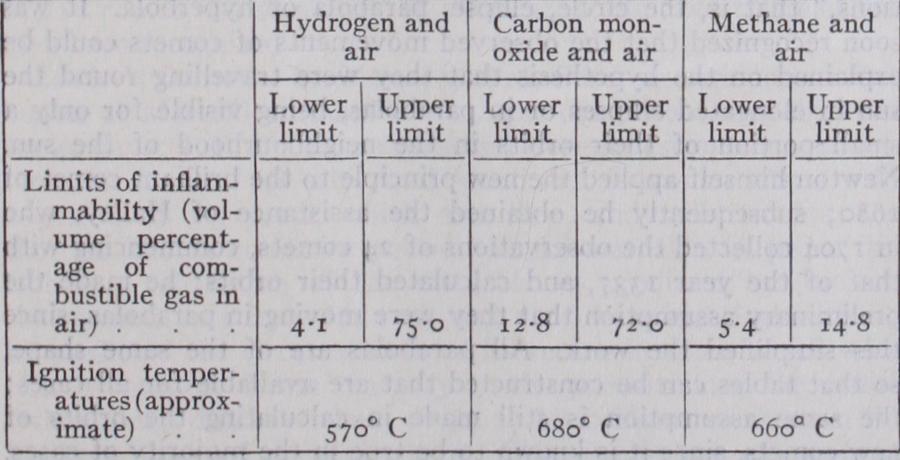

When a combustible gas issuing from an orifice is ignited, a stationary flame is maintained by the active chemical combination of the combustible with the oxygen of the atmosphere with which it intermingles. Should, however, the com bustible previously be mixed with air (or oxygen) in suitable proportion, the mixture becomes explosive, and given favourable conditions flame will be propagated through it. When such a mixture is ignited in a confined space, the heat developed raises the gases to a high temperature with consequent rapid increase in pressure. This explosion pressure is the source of power in gas and petrol-engines.In order that a gaseous mixture may be explosive it is necessary that the percentage of the particular combustible present should lie between certain limits. Also, in order to initiate flame the mix ture must be raised locally at least to its ignition temperature. In neither case are these conditions constant, but they are dependent on the temperature and pressure of the mixture and also on its environment. Usually, however, they can be reasonably well de fined; thus at atmospheric temperature and pressure the following figures have been found: It should also be borne in mind that in certain cases the elec trically charged state of the gases may play an important role in the initiation of flame.

Propagation of Flame.

In the case of mixtures of "limit" composition, the heat liberated by oxidation of the combustible is just sufficient to raise adjacent layers of gas to the "ignition temperature," flame being propagated only very slowly. When richer mixtures are exploded the nature of flame movement is dependent on circumstances. Thus if a mixture be ignited at the open end of a tube which is closed at the other end, an initial slow "uniform movement" usually occurs, its velocity being dependent on (I) the composition of the mixture, (2) its temper ature and pressure, (3) the nature and diameter of the tube employed, (4) the direction of flame propagation, and (5) the source and character of the ignition. Flame movement so initiated usually proceeds at uniform velocity for a certain distance and its termination is marked by a period of accelerated vibrational flame movement which may in certain cases give rise to detonation. When a mixture is ignited near the closed end of a tube the f or ward movement of the flame is continuously accelerated until ultimately detonation may be set up. It should also be mentioned that, when an explosive mixture is ignited in a state of turbulence, as in a gas engine, the rate of normal flame propagation (and hence pressure development) is much more rapid than if the mixture were stagnant.

Detonation.

When detonation (Fr. l'onde Explosive) oc curs, flame is propagated at an enormously high velocity (c. 2,000 to 3,00o metres per second), each successive layer of the explosive mixture concerned being ignited by adiabatic compression in an explosion wave. In such circumstances chem ical reaction is more intense and of much shorter duration than in normal combustion ; in addition, the pressure in the wave is much greater than that developed in ordinary explosions, thus accounting for its shattering effect. It is set up when a sufficiently explosive mixture is ignited by means of a detonator (e.g., a ful minate charge) or in circumstances such that an advancing flame is exposed to the effects of compression waves. When once estab lished, the velocity of the wave is constant and within wide limits unaffected by the material and diameter of the tube employed, being solely dependent on the nature of the explosive mixture, its temperature and pressure.(For heats of combustion, see THERMOCHEMISTRY.) See W. A. Bone and D. T. A. Townend, Flame and Combustion in Gases (I 92 7) ; R. T. Haslam and R. P. Russell, Fuels and their Combustion (1926). (D. T. A. T.)