Commercial Education

COMMERCIAL EDUCATION, being a recent develop ment of the educational system, is, in most countries, still in a state of transition, no adequate general plan having yet been adopted. The need for this type of education, however, has gradu ally become recognized, and in Great Britain and the United States considerable progress is being made.

The Education Act of 1918 led to the formation of Continua tion schools and classes under the London County Council and other educational authorities in Great Britain, and an association was formed for the advancement of education in industry and commerce. In the United States the Federal Board for Voca tional Education has also done active work in this direction.

(See CONTINUATION SCHOOLS.) The Institute.—The beginnings of public commercial educa tion in Britain may largely be ascribed to the activities of the mechanics' institutes in the early and middle periods of the i9th century, in which evening classes in both book-keeping and lan guages gradually grew up. These were succeeded by technical in stitutes, such as the Birmingham and Midland Institute and the Manchester High School of Commerce. In fact, up to 189o, and even later, the north of England and the Midlands were, as re gards commercial education, in advance of London and the rest of the country. In 1890 the school boards gained the right to undertake evening work. This ultimately led to the country being covered with a network of evening schools. The work at first was of a rather elementary nature, consisting of book-keep ing, shorthand, typewriting, English and often French. The Tech nical Education Act gave a considerable impetus to the spread of commercial education in polytechnics and similar institutions.

Still the movement had to face a good deal of opposition, or at least inertia, mainly from the widespread belief, which has not yet entirely disappeared and which is based on a half-truth, that com merce is best learned in the shop and the counting-house. Again, there was a good deal of muddle-headed thinking on the subject. Mr. Sidney Webb pointed out in a London conference held at the Society of Arts in 1897 that the term commerce covered a multi tude of things—a vast number of distinct callings, from account ancy and banking to typewriting. It therefore involved an educa tion of very varying degree, from elementary to university.

Universities.

Mr. Sidney Webb was largely responsible for the creation in 1895 of the London School of Economics and Political Science as an institute for higher commercial work. Beginning largely as a college for evening work, it subsequently developed a flourishing day side, and became a school of London university. Further developments in the course of higher educa tion were the creation of faculties of commerce in the University of Birmingham (1900) and the re-constituted University of Man chester (1904), while London in 1917 established a bachelorship and mastership of commerce. A commercial degree can also be obtained at Newcastle (University of Durham), and at Liverpool a B.A. is awarded for proficiency in certain commercial subjects.Economics figure as a prominent subject in the syllabus of other universities, but are taught mainly on theoretical lines, and no degree in commerce is obtainable. Probably the most complete choice of subjects for commercial study is offered by the London School of Economics and Political Science, amounting to nearly 2 70 courses given by some 8o lecturers and assistants. More than half of its departments are concerned wholly or partially with commerce. It prepares for the degrees of Bachelor of Commerce and Master of Commerce, and provides for research work.

Schools of Commerce.

Below the universities come the vari ous day schools of commerce, often forming a section or depart ment of a technical institute. The age of entry is generally 16, and some prepare for the B.Com. Such are for instance, the City of London College, The Regent Street Polytechnic Higher School of Commerce, the West Ham Technical Institute, with its course in commerce (three years), and the Manchester Municipal High School of Commerce. There are also junior commercial schools, where the age of entry is usually 13 and the course is two years (occasionally three) .

Secondary Schools.

Certain secondary schools, like Hackney Downs and Holloway (London) , prepare their students for de. grees in commerce, while at least one of the public schools (Brad field) has a definite commercial section. A large number of girls' secondary schools also do commercial work, which in many cases is confined to pupils who have passed the first school examination. In others it is begun by pupils of 15 who desire to specialize in commerce. Typewriting, shorthand and book-keeping, with com mercial French, history and geography, are the staple subjects.

Higher Elementary Schools.

Up to 1908 the curricula of the higher elementary schools were based on lines giving a gen eral education. In that year, the London schools of this type were reorganized with a dual bias, commercial and technical, and re named central—a school might have one or both sections. The London central schools largely became the model for other central schools for the rest of the country. In the voluntary day continu ation school the teaching, which at the outset was general, became, in London at least, largely commercial.

Evening Work.

Some evening work in the London School of Economics and elsewhere is of university standard. Below this ranks the work of the evening schools, many of which, especially in the country, are situated in technical institutes, notable exam ples being the Manchester and Birmingham Municipal Schools of Commerce, the Hull Central School of Commerce, the Bradford Commercial College, the City of London College and the 24 Lon don evening institutes.The range of work is considerable, and, apart from typewriting, shorthand and book-keeping, includes preparation for examina tions in accountancy of all kinds, banking, insurance (life, fire, marine), railway administration, civil service (post-office, inland revenue, customs and excise), courses for solicitors' or stock brokers' clerks, for secretaries or grocers' assistants. This involves classes in economics, including economic history and geography, and the economics of shipping, railways, etc. ; the theory and practice of commerce, banking, currency, foreign exchanges, sta tistics, the machinery of business, secretarial practice, knowledge of commodities, law of all kinds—general, conveyancing, bank ing, company, commercial, mercantile, marine, joint stock, income tax, etc.

The teaching of languages comprises French, German, Spanish, Italian and other less known languages, and Esperanto by the course system, all students under 18 who have not had a good secondary or central school education are obliged to take a course in which a language often forms a part. Students enter the insti tutes at sixteen. Below these are the junior institutes, usually entered at 14, where all pupils are obliged to take a course.

Private Initiative.

There also exist a number of schools attached to big business houses, as well as many private institu tions, which prepare mainly for the lower and intermediate walks of commerce and the civil service.

Examinations.

In addition to the examinations mentioned above, and some higher commercial certificates, a large number of students in the evening institutes and elsewhere take the exam ination of the Society of Arts, the Chamber of Commerce and other societies. The Society of Arts held its first practical exam ination in 1856, and among the subjects were French and book keeping. The candidates, mainly drawn from mechanics' insti tutes, numbered 56. In 1927 the number of papers worked was over 88,000. The London Chamber of Commerce, which began in 1890 with 65 candidates and 17 passes (all junior), had, in 1926, more than 25,000 worked papers. (C. BR.) The first commercial courses offered in the United States early in the i9th century were for the purpose of training book-keepers. Since 1894 commercial courses have included, besides book keeping, the subjects of typewriting and shorthand. Retail selling was added about ten years later.Early commercial training was given almost entirely in private commercial schools which recruited their students chiefly from the graduating classes of public elementary schools. Public pres sure for free commercial education, and business pressure for trained office workers possessing more than elementary schooling, put commercial courses in the curricula of urban high schools. In the beginning, the high school courses were mere copies of those offered in the private schools, and were taught, in the main, by teachers drafted from these institutions. In time, however, both teachers and courses were greatly improved. The better high schools now offer both short and long courses in the three fol lowing groups of work—(r) secretarial and recording, (2) accounting and (3) selling.

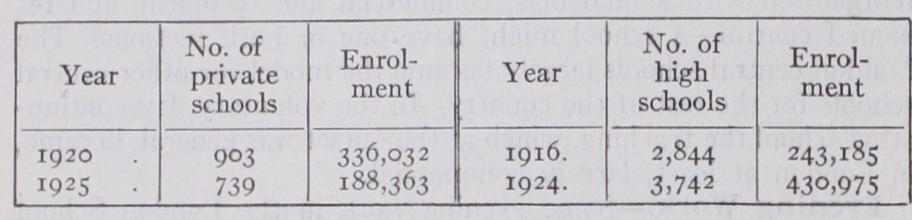

It is interesting to note that in the competition against the public high schools, the private commercial schools are steadily losing ground as the following statistics taken from a 1926 bulle tin of the United States Bureau of Education will show.

The introduction of commercial courses into high schools did not insure continued adjustment to the changing needs of a busi ness world in which commercial practices were gradually becoming highly specialized. A Congressional commission in 1916 reported "the quality of commercial education might be improved" and the Smith-Hughes act of 1917 placed definitely upon the newly created Federal Board for Vocational Education the responsibility for making surveys to determine the actual commercial education needs of the country. In its survey of commercial occupations in which workers 14 to 18 years of age are employed, the Federal board classified and analysed the following junior commercial occupations-0) general clerk, (2) shipping clerk, (3) receiving clerk, (4) stock clerk, (5) file clerk, (6) mail clerk, (7) typist, (8) billing clerk, (9) duplicating and addressograph machine operator, (ro) calculating machine operator, Or) office boy, 02) collector, 03) assistant book-keeper, (i4) entry clerk, (ID ledger clerk, 06) cost clerk, 07) book-keeping machine operator, 08) time-keeper, 09) statement clerk, (2o) stenographer, (2r) dictating machine operator, (22) junior sales person, (23) mes senger, (24) bundle wrapper, (25) cashier and (26) examiner. Following the presentation of the Federal findings, commercial continuation, high and evening schools greatly altered their cur ricula to meet more adequately the needs of junior workers who, in more cases than not, need training in other commercial courses than book-keeping, typewriting and stenography. The Federal Board has also been very active in assisting national associations of retail grocers, dry goods merchants, laundry owners and others in developing curricula suitable for the training. schools of the special commercial interests.

On the university level there is an unusually active development of schools of commerce and business administration. Besides spe cialized courses, these schools offer general opportunities in eco nomics, business law, finance, marketing and merchandising, and business organization and administration. The most recent addi tion to the curriculum to receive great attention is business ethics.

In their research investigations, these university schools are focusing their efforts upon the most perplexing problem business is facing—the economical distribution of goods. In the larger cen tres, also, these schools are affecting co-operative arrangements with business interests. Notable among these is the Meat Packers' institute affiliated with the University of Chicago.

(W. F. R.) Schools of Business.—The organization of professional schools of business in the United States is part of that broader educa tional trend which has given us schools of medicine, law, den tistry, agr;culture, engineering and journalism. The first school of commerce in the United States which could properly be re garded as of collegiate type was the Wharton school at the Uni versity of Pennsylvania, founded in 1881. During more than the first two decades of its existence it could boast little more than the conventional academic course interspersed with eco nomics, political science and sufficient mercantile law and account ancy to meet the stipulation of the school's founder that it afford "training suitable for those who intend to engage in business or to undertake the management of property." No other school was organized until 1898, when the University of California and the University of Chicago entered the lists. In 19oo the Uni versity of Wisconsin, Dartmouth college and New York university presented organized courses. The University of Michigan followed in Igor. Beginning with 19o8 growth accelerated, and by the end of 1925 no university was without some courses stressing educa tion for business. Many of the colleges of the country, large and small, have imitated this procedure on a minor scale.

Schools of business have often been classified according to con ditions set for student admission. In a number of instances, of which the Wharton school is typical, a student may be admitted at the end of his high school career to a course of study which covers four academic years and affords a mixture of general academic and more specific business instruction. In other in stances, of which the school at Columbia is a fair example, two pre-business college years must be completed in general academic subjects before a student may pass on to two or more special years of business study, and thence, if he so choose, to more advanced study of graduate character. At Dartmouth and Michigan, three years of college work are required for admission to a two-year business course leading to a master's degree; and at Harvard and Leland Stanford the schools of business require college graduation for admission to a course leading to a master's degree. Most of the urban institutions have developed continuation courses, often highly specialized, for students not interested in an academic degree.

Owing to varying maturity of students resulting from divergent entrance requirements, and other more local reasons, school ob jectives as well as curricula show considerable diversity. In many instances the aim has been loosely expressed as "training for busi iness," and the resulting curriculum is a loose collection of busi ness courses adapted to immediate practical needs. But among the older and better organized schools there is gradually emerg ing a conception of objective which stresses preparation for ulti mate managerial responsibility. The aim is to afford business knowledge which is transferable and typical of many fields of business enterprise, and gives its possessor freedom and power rather than narrowly focussed skill leading to fixity of occupa tional status. Resulting curricula, therefore, are tending less to depict business routine, and more to stress fundamentals, at least as a basis for possible subsequent specialization. A background of geographic knowledge and technology, acquaintance with lan guage, accounting and statistics, familiarity with business struc ture and function, and its place in the broader fabric of society, have all come to be regarded as essentials of instruction. Beyond this there is a growing array of opportunities for study and re search in special fields such as production, marketing, finance, transportation and insurance, with increasing emphasis in the larger urban institutions on specialized and technical phases of current practice and experimentation. Methods of instruction for the most part follow the usual college types; but in a few in stances distinctive methods have been evolved. At Cincinnati practice in active business is co-ordinated with theory at school on a supervised co-operative basis; and at Harvard a case method of instruction is being perfected, somewhat along law school lines, to give realistic quality to class work and afford a synthetic view of business administrative devices and judgments which by other methods can be treated only hypothetically and as segre gated phases of practice. But all of these problems of curriculum and of teaching method are still in a highly fluid state. Business research in a variety of forms is pursued in a number of schools, and in the stronger ones their research activities are guided by regularly organized bureaux. The American Association of Col legiate Schools of Business through its information service pro motes co-ordination and avoidance of duplication in research projects. The association likewise affords a forum for discussion of general school problems. Two periodicals, The Harvard Busi ness Review and The Journal of Business (Chicago), besides ir regularly issued publications, furnish scientific discussion of edu cational and business problems. (R. C. McC.) COMMERCIAL FEDERATION: see CUSTOMS UNION. COMMERCIAL LAW, a term used rather indefinitely to include those rules and principles which govern commercial trans actions and customs. It includes within its compass such titles as principal and agent ; carriage by land and sea; merchant ship ping; guarantee; insurance; bills of exchange; partnership; limit ed companies; bankruptcy, etc.