Congo Free State

CONGO FREE STATE, the name used by British writers for the Etat Independant du Congo, a state of equatorial Africa which occupied most of the basin of the Congo river. In 1908 the state was annexed to Belgium. The present article deals with the history of the state ; for later events see BELGIAN CONGO.

The state owed its existence to the ambition and force of charac ter of a single individual, Leopold II., king of the Belgians. Inter est in Central Africa had been greatly stimulated in the middle of the 19th century by the discoveries of David Livingstone, J. H. Speke, Richard Burton and others, and in 1876 King Leopold summoned in Brussels a conference of geographical experts which resulted in the creation of "The International Association for the Exploration and Civilization of..Af rica." National committees were formed in various countries and an international commission was instituted with headquarters in Brussels. The Belgian committee devoted attention first to East Africa, but the arrival in Aug. 1877 of H. M. Stanley at the mouth of the Congo, which marked the end of the great journey in which he discovered the course of that magnificent river, at once turned Leopold's thoughts to the im mense possibilities offered by the development of the Congo basin. Having tried in vain to interest British merchants in the develop ment of the region, Stanley in Nov. 1878, accepted Leopold's offer to return to the Congo, build a chain of stations on the banks of the river, open a road through the cataract region separating the estuary from the navigable waters above, and to conclude agreements with the native chiefs. A separate committee of the International Association was formed in Brussels, under the name of Comite d'etudes du Haut Congo; this committee afterwards be came the International Association of the Congo. Though inter national in name the association soon carne entirely under the direction of King Leopold and his associates. Stanley, as agent of the association, spent four years in the Congo, founding stations and making friendly agreements with various chiefs. The first station was founded at Vivi in Feb. 1880.

Recognition by the Powers.—Bef ore Stanley's return to Europe the work of the association had attracted much attention among the powers interested in Africa. A little tardily the impor tance of the newly-discovered regions was realized. On behalf of France M. de Brazza had reached the Congo from the north and had established various posts, including one, the present Brazza ville, on Stanley Pool (see FRENCH EQUATORIAL AFRICA). Por tugal, on the strength of the discovery of the mouth of the Congo by her navigators in the 15th century, advanced claims to sov ereignty over both banks of the estuary of the river. These claims were recognized by the British Government in a convention con cluded in Feb. 1884. This convention aroused much opposition, especially in Great Britain and Germany, and was never ratified. It led directly to the summoning of the Berlin Conference of 1884-85, and to the recognition of the International Association as a sovereign state. Such recognition had been King Leopold's aim. In any case the position of the association was anomalous. On the Congo itself there was no one great native state ; the region was under the rule of a vast number of petty chiefs. This made it comparatively easy for the association, locally, to assume supreme authority. The United States of America, where Leopold's aims and Stanley's work attracted much sympathy, was the first great power, in a convention signed April 22, 1884, to recognize the as sociation as a properly constituted state. At this time King Leo pold was negotiating with France not only for recognition of the association but on boundary questions. Negotiations were con ducted by and in the name of the president of the association, Col. M. Strauch, a Belgian officer. By a note of April 23, 1884, Col. Strauch gave France the right of pre-emption—the first right to purchase—should the association be compelled to sell its posses sions.

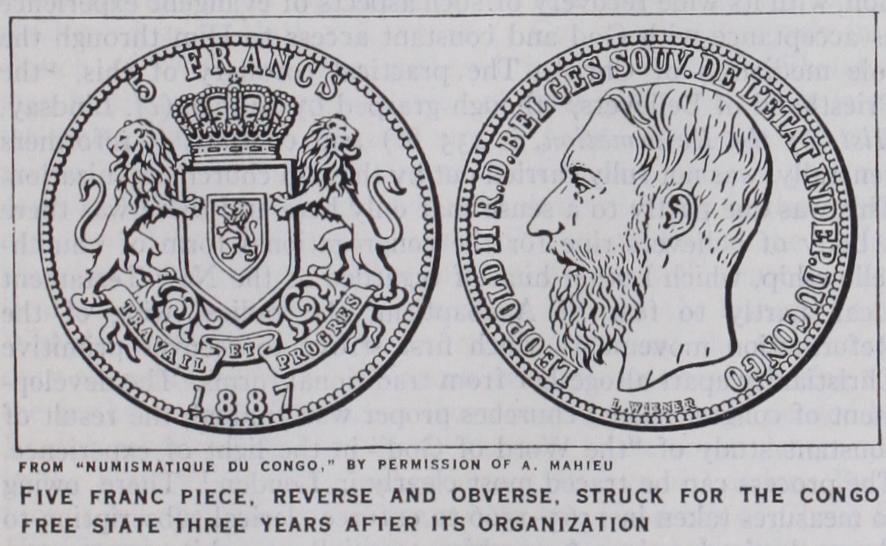

In 1887 it was announced by the Congo State that this preferen tial right granted to France in 1884 was not intended to be opposed to the rights of Belgium, and in fact Belgium ultimately acquired the Congo State. While the negotiations with France were pro ceeding Germany recognized the independence of the association (Nov. 8, 1884). This was followed by recognition by Great Britain (Dec. 16, 1884) and other Powers. Owing to difficulties in reach ing agreement as to boundaries, French recognition was delayed until Feb. 5, 1885; that of Portugal followed on Feb. 14.

While the negotiations for recognition were going on the Berlin congress on African affairs met. Some of its decisions directly affected the International Association. A conventional basin of the Congo was defined, and in this conventional basin it was declared that "the trade of all nations shall enjoy complete freedom." Free dom of navigation of the Congo and all its affluents was also secured, and differential dues on vessels and merchandise were forbidden. Trade monopolies were prohibited, and provisions made for the suppression of the slave trade, and the protection of mis sionaries, scientists and explorers. Provision was also made for the Powers owning territory in the conventional basin to proclaim their neutrality. The International Association not having pos sessed, at the date of the assembling of the conference (Nov. 15, 1884) any recognized status, was not formally represented at Berlin, but the flag of the association having, before the close of the conference, been recognized as that of a sovereign state by all the powers, with the exception of Turkey, the association formally adhered to the General Act signed by the delegates to the confer ence on Feb. 26, 1885.

Leopold's next step was to assume his place as the sovereign of the new state. The Belgian Chamber in April 1885 authorized the king "to be the chief of the state founded in Africa by the Inter national Association of the Congo" and declared that "the union between Belgium and the new state of the Congo shall be exclu sively personal." The formal proclamation of the king's sovereign ty was made on July 1, 1885, at Boma (on the north bank of the lower Congo) by Colonel (later Sir) Francis de Winton, who had succeeded Stanley as head of the local administration. This was followed by a circular letter sent to the Powers on Aug. 1 by King Leopold in which he declared the perpetual neutrality of "the In dependent State of the Congo" and set out the frontiers then claimed by the state. The king had been compelled to yield to France considerable areas in the Congo basin, including the north bank of the river itself from Stanley Pool to the confluence with the Ubangi ; Portugal obtained the south bank of the river from its mouth up to Noki. In a race with British agents for unappropria ted regions Leopold succeeded in securing for the Congo Free State the highly mineralized region of Katanga and the only part of the Congo basin where white settlement on any scale is possible.

It was not until 1894 that an agreement was made with Great Britain defining the frontier with British possessions in Central Africa. By this agreement King Leopold also attained, for a time, an outlet on the Nile for the Congo State. This was one of his great ambitions and he had sent more than one expedition to the Upper Nile. Now by the 1894 agreement he obtained a lease from Great Britain of the Bahr-el-Ghazel province. However, in 1906 the lease was annulled, though King Leopold was permitted during his reign to hold the Lado Enclave. The whole episode was part of the struggle for supremacy in the Upper Nile and of the British efforts to obtain an "All-Red" route from the Cape to Cairo. (See AFRICA : History.) The Arab War. While seeking to extend the boundaries of the state the administration had many internal difficulties to over come. Much energy was shown in establishing posts along the Congo itself and its main afuents; from the first steamers had been placed on the river and it was early determined to build a railway round the cataract region so that the produce of the upper river could be brought more easily to the markets of the world. The avowed object of the Free State was to develop the resources of the country with the aid of the natives and to the mutual bene fit of blacks and whites. But it soon became apparent that the Arab slave-traders, mostly of Zanzibar origin, who had established themselves in the country between Lake Tanganyika and Stanley Falls were a serious obstacle to any progress over a large region. The state was poor—its revenues had to be supplemented from the private purse of King Leopold—and a cautious policy was enjoined on its officers who were brought into relations with the Arabs on the upper river, of whom Tippoo-Tib was the chief. In 1886 the Arabs had destroyed the state station at Stanley Falls, and it was apparent that a struggle for supremacy was inevitable. But the Free State was at that time ill prepared for a trial of strength, and at Stanley's suggestion the bold course was taken of appointing Tippoo-Tib governor of Stanley Falls, as the represen tative of King Leopold. This was in 1887, and for five years the modus vivendi thus established continued. During those years fortified camps were established by the Belgians on the Sankuru, the Lomami, and the Arumiwi, and the Arabs were quick to see that each year's delay increased the strength of the forces against which they would have to contend. In 1891 the imposition of an export duty on ivory excited much and when it became known that, in his march towards the Nile, van Kerckhoven had defeated an Arab force, the Arabs on the upper Congo determined to precipitate the conflict. In May 1892 the murder of M. Ho dister, the representative of a Belgian trading company, and of ten other Belgians on the upper Lomami, marked the beginning of the Arab war. When the news reached the lower river a Belgian expedition under the command of Commandant (afterwards Baron) Dhanis was making its way to wards Katanga. This expedition was diverted to the east, and, after a campaign lasting several months, during which the Arab strong holds of Nyangwe and Kasongo were captured, the Arab power was broken and many of the leading Arabs were killed. The political and commercial results of the victory of the Free State troops were of great importance; henceforth the Free State was master of its own house. Rather it was master over the greater part. In 1895 there was a revolt of the Batetelas in the Lulua and Lomami districts. The mutineers were defeated ; but in 1897 the Batetelas again revolted and took possession of a large area of the eastern portion of the state. The mutineers were not finally dis persed until near the end of 1 goo. In other parts of the country the state had difficulties with native chiefs, several of whom pre served their autonomy. In the central Kasai region the state had been unable to make its authority good up to the time it ceased to exist.

Although in 1885 the Belgian Parliament had declared that the union between Belgium and the Congo was purely personal it had been foreseen that the union would become closer. In 1889 King Leopold made public certain terms of his will, dated Aug. 2 of that year, in which he bequeathed to Belgium "all our sovereign rights over the Independent State of the Congo." This was a preliminary to a request for financial help, and in 18go Belgium granted a loan, receiving in return the option of annexing the Congo state at the end of a period of ten years and six months. Further financial diffi culties led to a proposal, eventually defeated, for the annexation of the state to Belgium as from Jan. 1, 1895, and this proposal led to a Franco-Belgian convention (Feb. 5, 1895) in which the Belgian Government recognized "the right of preference possessed by France over its Congolese possessions in case of their compulsory alienation in whole or in part." In Igo 1 the question of the annex ation of the Free State again formed the subject of prolonged dis cussion in the Belgian Parliament. It was decided at that time not to exercise the option possessed under the terms of the 1890 loan. At that period (Igo' ) King Leopold opposed the immediate an nexation of the state.

The Charges of Maladministration.

By this time charges highly injurious to the administration of the Free State had been publicly made. It was admitted that the state, as far as it could, had suppressed cannibalism, that it had strictly enforced anti liquor laws, and had broken the power of the Arab slavers, but it was accused of robbing the natives of their rights, of suppressing freedom of trade and even of countenancing "atrocities." The dis cussions in the Belgian Parliament on the affairs of the Congo State were greatly embittered by these charges. The administra tion of the state had indeed undergone a complete change since the early years of its existence. A decree of July 1, 1885, had, it is true, declared all "vacant lands" the property of the state (Do maine prive de l'etat), but it was not for some time that this decree was so interpreted as to confine the lands of the natives to those they lived upon or "effectively" cultivated. Their rights in the forest were not at first disputed, and the trade of the natives and of Europeans was not interfered with. But in 1891—when the wealth in rubber and ivory of vast regions had been demonstrated —a secret decree was issued (Sept. 21) reserving to the state the monopoly of ivory and rubber in the "vacant lands" constituted by the decree of 1885, and circulars were issued making the monop oly effective in the Aruwimi-Welle, Equator and Ubangi districts. The agents of the state were enjoined to supervise their collection, and in future natives were to be obliged to sell their produce to the state. By other decrees and circulars (Oct. 30, Dec. 5, 1892, and Aug. g, 1893) the rights of the natives and of white traders were further restricted. The effect of these later decrees was to assign to the Government an absolute proprietary right over nearly the whole country ; a native could not even leave his village without a special permit. The oppressive nature of these measures drew forth a weighty remonstrance from the leading officials, and C. Janssen, the governor, resigned. Vigorous protests by the private trading companies were also made against this violation of the freedom of trade provided for by the Berlin Act, and eventually an arrange ment was made by which certain areas were reserved to the state and certain areas to private traders, but the restrictions imposed on the natives were maintained. The "concession" companies were first formed in 1891. In all of the companies the state had a financial interest as shareholder or as entitled to part profits.This monopolist system of exploitation was fruitful of evil. It involved, in many cases, oppressive treatment of the natives. Only in the lower Congo and a narrow strip of land on either side of the river above Stanley pool was there any freedom of trade. The situation was aggravated by the creation in 1896, by a secret decree, of the Domaine de la couronne, a vast territory between the Kasai and Ruki rivers, covering about 112,000 sq.m. To ad minister this domain, carved out of the state lands and treated as the private property of Leopold II., a Fondation was organized and given a civil personality. It was not until Iq02 that the exist ence of the Domaine de la couronne was officially acknowledged.

The

Fondation controlled the most valuable rubber region in the Congo, and in that region the natives appeared to be treated with great brutality. In the end of the 19th century and the early years of the loth the charges brought against the state assumed a more and more definite character and gave rise to a strong agitation against the Congo State in the United States and elsewhere.

Action by Great Britain.

The agitation was particularly vigorous in Great Britain, and the movement entered on a new era when on May 20, 1903, the House of Commons agreed without a division to a motion requesting the Government to confer with the other signatories of the Berlin Act, "by virtue of which the Congo Free State exists, in order that measures may be adopted to abate the evils prevalent in that state." Representations to the powers made by the British Foreign Of fice followed, but evoked no official response—except from Tur key. In Great Britain however the agitation was greatly strength ened by the publication of a report made by Mr. (later Sir) Roger Casement (q.v.), then British consul at Boma, on a journey he had made in 1903 on the Congo above Stanley Pool.' The Congo administration denied most of the charges made in the Casement report—in particular it adduced evidence going to show that the cases of mutilation of natives which had occurred were neither the work of nor approved by the agents of the state, but were custom ary punishments inflicted by the chiefs on their people ; methods of barbarism which the state had not so far been able to eradicate. The efforts to disprove the charge that the state had become a monopolistic trading concern, to the detriment of the natives as well as to would-be white merchants, were not successful. Belgian public opinion was aroused and critical, and this led to the appoint ment by King Leopold in July 1904 of a commission of enquiry to visit the Congo.The Commission of Enquiry.—The commission was com posed of M. Edmond Janssens, advocate-general of the Belgian Cour de Cassation, who was appointed president ; Baron Giacomo Nisco, president ad interim of the court of appeal at Boma; and Dr. E. de Schumacher, a Swiss councillor of state and chief of the department of justice in the canton of Lucerne. Its stay in the Congo State lasted from Oct. 5, 1904, to Feb. 21, 1905, and its report appeared in Nov. 1905. While expressing admiration for the signs which had come under its notice of the advance of civiliza tion in the Congo State, the commission confirmed the reports of the existence of grave abuses in the upper Congo, and recom mended a series of measures which would, in its opinion, suffice to ameliorate the evil. It approved the concessions system in prin ciple and regarded forced labour as the only possible means of turning to account the natural riches of the country, but recognized the need for a liberal interpretation of the land laws, effective application of the law limiting the amount of labour exacted from the natives to 4o hours per month, the withdrawal from the con cession companies of the right to employ compulsory measures, the regulation of military expeditions, and the freedom of the 'Roger Casement's association with Germany during the World War led to a legend that Germany had fomented the Congo atrocities agitation for her own purposes. There was no evidence to support this legend. Neither did Casement's treason in 1914-16 affect the truth of a report made in 1903.

courts from administrative tutelage. Simultaneously with the report of the commission of enquiry, a decree was published ap pointing a commission to study the recommendations contained in the report, and to formulate detailed proposals. The report of the reforms commission was not made public, but as the fruit of its deliberations King Leopold signed on June 3, 'goo, decrees em bodying various changes in the administration of the Congo State. By the advocates of radical reforms these measures were regarded as utterly inadequate, and even in Belgium, among those friendly to the Congo State system of administration, some uneasiness was excited by a letter which was published along with the decrees, wherein King Leopold intimated that certain conditions would attach to the inheritance he had designed for Belgium. Among the obligations which he enumerated as necessarily and justly rest ing on his legatee was the duty of respecting the arrangements by which he had provided for the establishment of the Domaine de la couronne and the Domaine prive de l'etat.

Annexation by Belgium.

The Belgian Parliament looked with disfavour on this latest indication of King Leopold's policy and in Dec. 1906 resolved that a committee appointed in Igo' to study the conditions which should govern the Congo State when it became a Belgian possession should "hasten its labours." While the committee was sitting, further evidence was forthcoming that the system complained of on the Congo remained unaltered, and that the "reforms" of June 1906 were illusory. Not only in Great Britain and the United States did the agitation against the adminis tration of the Congo State gain ground, but in Belgium and France reform associations enlightened public opinion. The Government of Great Britain let it be known that its patience was not in exhaustible, while the Senate of the United States declared that it would support President Roosevelt in his efforts for the amelior ation of the condition of the inhabitants of the Congo.It was clear that Belgium would have to undertake responsibil ity for the Free State before long, and in Nov. 1907 a treaty was signed for the cession of the state. Some of its terms revealed clearly the proprietorial attitude Leopold adopted. These terms stipulated for the maintenance of the Fondation de la couronne. This "government within a government" was secured in all its privileges, its profits as heretofore being appropriated to allow ances to members of the royal family and the maintenance and development of "works of public utility" in Belgium and the Con go, those works including schemes for the embellishment of the royal palaces and estates in Belgium and others for making Ostend "a bathing city unique in the world." The state was to have the right of redemption on terms which, had the rubber and ivory produce alone been redeemed, would have cost Belgium about £8,500,000. These terms were preposterous and had not long been published before it was realized that the treaty would not be accepted by the Belgian Parliament unless they were modified. So negotiations were begun again. While they were in progress the British Government again expressed its views, and in very moni tory language. In Feb. 1908 a British parliamentary paper was issued (Africa No. r, 1908) containing consular reports on the state of affairs in the Congo. Mr. W. G. Thesiger, consul at Boma, in a memorandum on the application of the labour tax, of ter de tailing various abuses, added, "The system which gave rise to these abuses still continues unchanged, and so long as it is unaltered the condition of the natives must remain one of veiled slavery." On the same day the British foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey (afterwards Viscount Grey of Fallodon, q.v.), declared that the Congo State had "morally forfeited every right to international recognition." This declaration by Sir Edward Grey, together with the report of W. G. Thesiger, a man whose testimony was unimpeachable, virtually ended the conflict. King Leopold hastened to make such terms as he could. On March 5, 1908, an additional act was signed in Brussels annulling the clauses in the treaty of cession concerning the Fondation, though the king obtained very generous compensation for the surrender of that domain. Finally the Bel gian Chamber, after some four months' debate adopted, Aug. 20, 1908, the treaty of cession, the additional act and a law setting out the principles upon which the new colony should be governed.

These measures were voted by the Senate on Sept. 9 following, and on Nov. 14 of the same year the "Congo Free State" ceased to exist. On Nov. 15 the Belgian Government assumed authority without ceremony of any kind.

This assumption of authority by Belgium was not lightly under taken, as was shown by the legislature having had the matter under consideration for 14 years. Public opinion in Belgium was per turbed by the prospect of taking over the administration of a vast, distant and badly administered territory, likely to be for years a severe financial drain upon the resources of Belgium. But Belgium assumed its heavy task with the determination that as a colonial possession the Congo territory should be honestly governed, and in real agreement with the humanitarian principles which Leopold II. had never ceased to profess. And though it was widespread that there had been in practice many and grievous shortcom ings, there was recognition of the work Leopold II. had accom plished.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-H. M.

Stanley, The Congo and the Founding of Bibliography.-H. M. Stanley, The Congo and the Founding of its Free State (1885), an indispensable work for the beginnings of the state; A. Chapeaux, Le Congo, historique, diplomatique . . . (Brussels, 1894), and A. J. Wauters, L'Etat independant du Congo (Brussels, 1899), good general accounts; D. C. Boulger, The Congo State (1898), a defence of King Leopold; Prof. E. Cattier, of Brussels University, Etude sur la situation de l'etat independant du Congo (Brussels, 1906), a severe criticism of the Congo administration. The two following books are direct indictments of the Leopoldian regime:— H. R. Fox Bourne, Civilization in Congoland (19°3) ; E. D. Morel, King Leopold's Rule in Africa 0904) ; Mark Twain, King Leopold's Soliloquy (London, 19o7) is a bitter satire. A. Vermeersch, La Question Congolaise, is another indictment of Free State methods. The Fall of the Congo Arabs, by S. L. Hinde (1897), is an account of the campaign of 1892-93 by an English surgeon who served in the state forces. Of official documents the Protocols and General Act of the West African Conference (1885) is a British Blue Book and Nos. 9 and io of the Bulletin Officiel of the Free State (published monthly in Brussels, 1885-1908) contain the report of King Leopold's com mission of enquiry. A. J. Wauters and A. Buyl published in Brussels (18q5) a Bibliographie du Congo 188o–g5 which contains 3,800 entries. A British White Paper, Correspondence and reports . . . respecting the administration of the . . . Congo (19o4) gives R. Casement's re port and Africa No. 1, igo8 gives W. G. Thesiger's report.(F. R. C.)