Connecticut

CONNECTICUT (ko-net'i-kilt), called the "Nutmeg State," is one of the 13 original States of the Union, and one of the New England group. It is bounded north by Massachusetts, east by Rhode Island, south by Long Island sound, and west by New York; the south-west corner projects along the sound indenting New York for about 13 miles. The State is situated between 40° 54' and 3' N. and between 71 ° 47' and 43' W., and its total area is 4,965 sq.m., of which 145 are water surface. Only two States of the Union, Rhode Island and Delaware, are smaller in area. The popular name "Nutmeg State" was given to Connecticut because of an alleged practice, on the part of some of the State's earlier citizens, of manufacturing and selling wooden nutmegs as genuine.

Physiography.---Connecticut

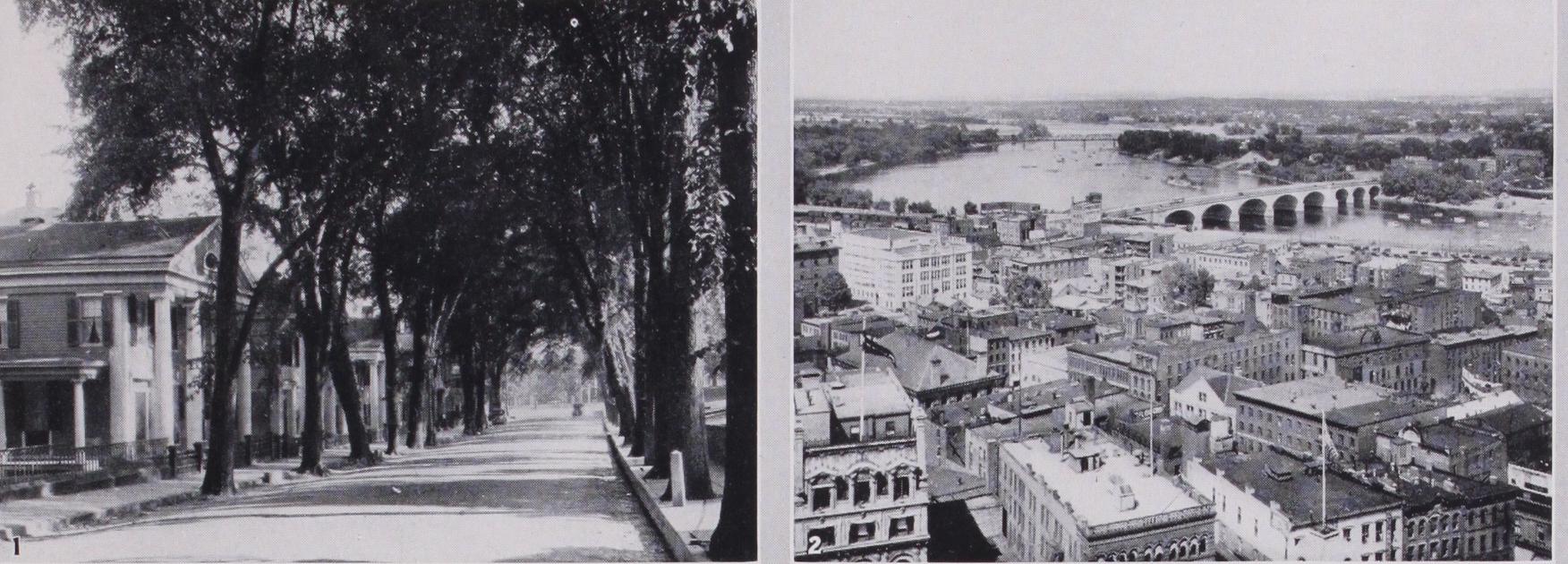

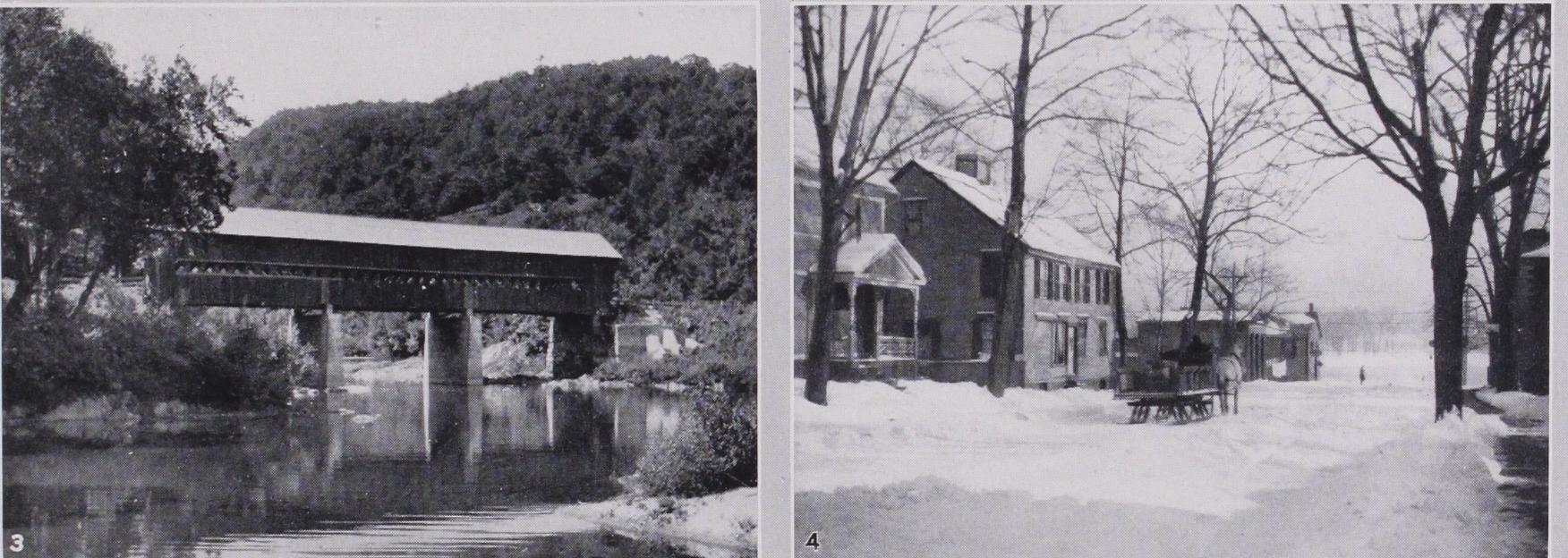

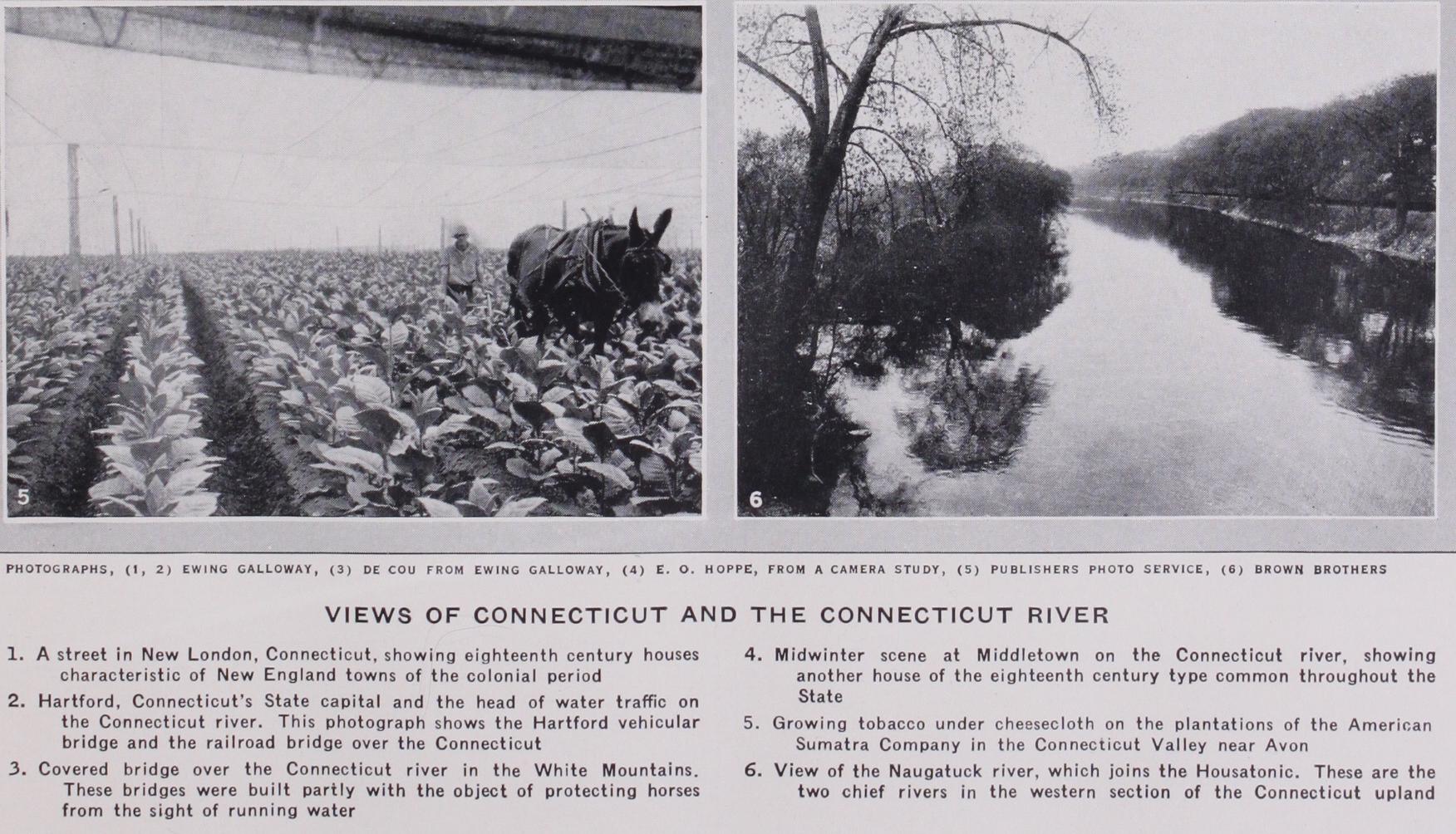

lies in the south portion of the peneplain region of New England. Its surface is in general that of a gently undulating upland divided near the middle by the low land of the Connecticut valley, the most striking physiographic feature of the State. The upland rises from the low south shore at an average rate of about loft. in a mile until it has a mean ele vation along the north border of the State of I,000ft. or more, and a few points in the north-west rise to a height of about 2,000f t. above the sea. The lowland dips under the waters of Long Island sound at the south and rises slowly to a height of only Iooft. above them where it crosses the north border. At the north the lowland is about 15m. wide; at the south it narrows to only 5m. ; its total area is about 600 sq.m. Its formation was caused by the removal of a band of weak rocks by erosion after the general upland surface had been first formed near sea level and then elevated and tilted gently south or south-east; in this band of weak rocks were several sheets of hard igneous rock (trap) in clined from the horizontal several degrees, and so resistant that they were not removed but remained to form the "trap ridges," such as West Rock ridge near New Haven and the Hanging hills of Meriden. These are identical in origin and structure with Mt. Tom range and Holyoke range of Massachusetts, being the south con tinuation of those ranges. The ridges are generally deeply notched, but their highest points rise to the upland heights directly to the east or west. The west section of the upland is more broken than the east section, for in the west are several isolated peaks lying in line with the south continuation of the Green and the Housatonic mountain ranges of Vermont and Massachusetts, highest among them being: Bear mountain, 2,355ft., Gridley mountain, 2,2ooft., Mt. Riga, 2,000f t. ; Mt. Ball and Lion's Head, each 1, 76of t. ; Canaan mountain (North Canaan), 1,68oft.; and Ivy mountains (Goshen) 1,64oft. Just as the surface of the lowland is broken by the notched trap-ridges, so that of the upland is often inter rupted by rather narrow deep valleys, or gorges, extending usu ally from north to south or to the south-east. The lowland is drained by the Connecticut river as far south as Middletown, but here this river turns to the south-east into one of the narrow valleys in the east section of the upland, the turn being due to the fact that the river acquired its present course when the land was at a lower level and before the lowland on the soft rocks was excavated. The principal rivers in the west section of the upland are the Housatonic and its affluent, the Naugatuck; in the east section is the Thames, which is really an outlet for three other rivers (the Yantic, the Shetucket and the Quinebaug). In the cen tral and north regions of the State the course of the rivers is rapid, owing to a relatively recent tilting of the surface. The Connecti cut river is navigable as far as Hartford, and the Thames as far as Norwich. The Housatonic river, which in its picturesque course traverses the whole breadth of the State, has a short stretch of tide-water navigation. The lakes which are found in all parts of the State and the rapids and waterfalls along the rivers are largely due to disturbances of the drainage lines by the ice invasion of the glacial period. To the glacial action are due also the extensive removal of the original soil from the uplands and the accumula tion of morainic hills in many localities. The sea coast, about 10o m. in length, has a number of bays, making several good har bours which have been created by a depression of small valleys.

The climate of Connecticut, though temperate, is subject to sudden changes, yet the extremes of cold and heat are less than in the other New England States. The mean annual temperature is F, the average temperature of winter being - 2-7 ° and that of summer 7 2 °. Since the general direction of the winter winds is from the north-west, the extreme of cold (-10° or-15°) is felt in the north-western part of the State. The prevailing summer winds, which are from the south-west, temper the heat of summer in the coast region, but extreme heat (100°) is found in the central part of the State. The annual rainfall varies from 45 to so inches.

Government.

The present constitution of Connecticut is that framed and adopted in 1818 with subsequent amendments (37 up to 1927). Amendments are adopted after approval by a majority vote of the lower house of the general assembly, a two-thirds ma jority of both houses of the next general assembly, and ratifica tion by the townships. The executive and legislative officials are chosen by the electors for a term of two years, the attorney-gen eral for four years ; the judges of the supreme court of errors and the superior court, appointed by the general assembly on nomina tion by the governor, serve for eight years, and the judges of the courts of common pleas (in Hartford, New London, New Haven, Litchfield and Fairfield counties) and of the district courts, chosen in like manner, serve for four years. In providing for the judicial system, the constitution says : "the powers and jurisdic tion of which courts shall be defined by law." The general assem bly has interpreted this as a justification for interference in legal matters. It has at various times granted divorces, confirmed faulty titles, annulled decisions of the justices of the peace, and validated contracts against which judgment by default had been secured. Qualifications for suffrage are : the age of 21 years, citi zenship in the United States, residence in the State for one year and in the township for six months preceding the election, a good moral character, and ability "to read in the English language any article of the constitution or any section of the statutes of this State." The right to decide upon a citizen's qualifications for suf frage is vested in the select men and clerk of each township. A property qualification, found in the original constitution, was re moved in 1845. The 15th amendment to the Federal Constitu tion was ratified (1869) by Connecticut, but negroes were ex cluded from the suffrage by the State Constitution until 1876.

The jurisprudence of Connecticut, since the 17th century, has been notable for its divergence from the common law of England. In 1639 inheritance by primogeniture was abolished, and this re sulted in conflict with the British courts in the i8th century. At an early date, also, the office of public prosecutor was created to conduct prosecutions, which until then had been left to the ag grieved party. A homestead entered upon record and occupied by the owner is exempt to the extent of $1,000 in value from liability for debts. There were 35 members in the senate and 267 in the house of representatives in 193o.

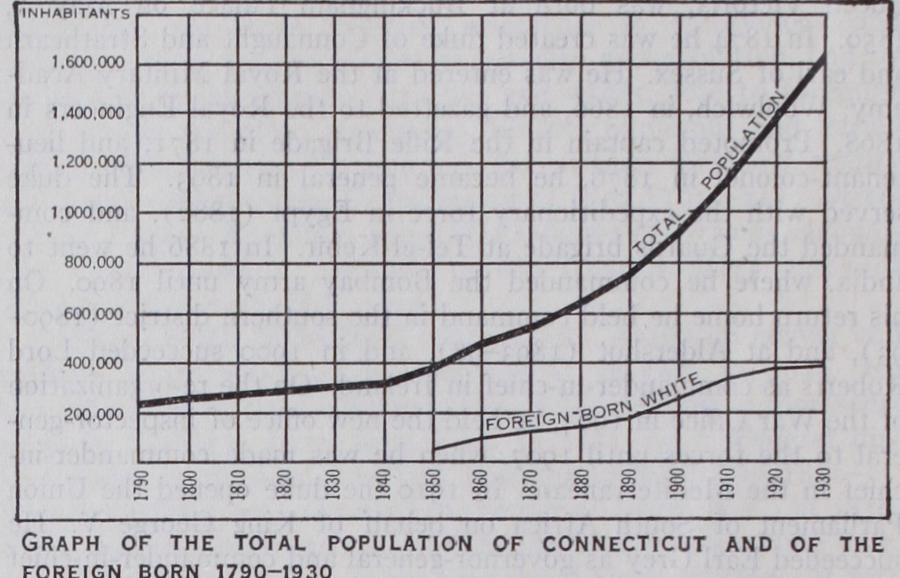

Population.

The population of Connecticut in 1790 was 237, in i800, 251,002; in 185o, 370,792; in 188o, 622,700; in 1900, 908,420; in 1910, 1,114,i56; and in 192o, 1,380,631, an increase for that decade of 23.9%; in 193o it was by United States census 1,606,903, an increase of 226,272, or 16.4%. Of the 193o population 98.1% were white and 23.8% were foreign-born, and only 33.5% of the native whites were of full native parentage. Of the foreign-born element 22.8% were Italian; 12.9% Polish; and io.i% Irish. This shows a change from the leadership of the Irish with 29.8% in 1900. There were also many Russians, French-and-English-Canadians, English, Germans and Swedes. The urban population was 7o.4% of the total in 193o. In 193o there were 18 cities and two boroughs with a population of more than io,000. Cities in the State having a population of more than 30,00o in 193o were Hartford, 164,072 ; New Haven, 162,655; Bridgeport, 146,716; Waterbury, 99,902; New Britain, 68,128; Stamford, 46,346; Meriden, 38,481; Norwalk, 36,019.

Finance.

The report of the State treasurer for the fiscal year ending June 3o, 1932, for State and local governments' revenue receipts of $128,221,854; governmental costs, $138,885,620; gen eral property tax levies, $75,6o9,776. The gross debt, less sinking fund assets, amounted to $160,700,082. The principal sources of revenue were : the motor vehicle license fees; an inheritance tax; a gasolene tax of two cents per gallon ; a net income corporation tax; a tax on steam railways; a State tax on towns; taxes on sav ings banks; and a tax on stock insurance companies. The State has no personal income tax. There is a military commutation tax of $2, and all persons neglecting to pay it are liable to imprison ment. A State board of equalization has been established to in sure equitable taxation. The legal rate of interest is 6% and days of grace are not allowed.Education.—Education has always been a matter of public interest in Connecticut. Soon after the foundation of the colonies of Connecticut and New Haven, schools similar to the English grammar schools were established. The Connecticut code of 165o required all parents to educate their children, and every township of 5o householders (later 3o) to have a teacher supported by the men of family, while the New Haven code of 1656 also encour aged education. In 1672 the general court granted 600ac. of land to each county for educational purposes; in 1794 the general as sembly appropriated the proceeds from the sale of western lands to education, and in 1837 made a similar disposition of funds re ceived from the Federal treasury.

Beginning on July 15, 1909, the organization of public educa tion was changed from the dis trict type to town management type. In 1921 there were less than ten townships that had not availed themselves of the law by which all the schools are under the direction of the town school committee. Appropriations for the support of the schools are made at a town meeting. Com pulsion was made more rigid by the enactment providing that after Sept. 1, 1911, no employment certificate should be accepted by any employes, except certificates issued by the State board of education.

There were 388,515 children between the ages of 5 and 17 in clusive, in 1932. Of this number, 325,493, or 79%, were enrolled in the public schools, and 63,022 of the remainder attended pri vate or parochial schools. The public school attendance con sisted of 252,935 in the kindergarten and elementary schools and 72,558 in the secondary schools. Fifty-six private high schools and academies helped to lessen the public secondary school at tendance. The average days attended per year per pupil enrolled in the public schools was 158.2. The public school expenditure for 1932 was $33,733,000--or $81.88 per head of the population between 5-17 years, inclusive. The State maintains trade schools, which had an enrolment of 4,732 in 1930 and helps in the maintenance of two others. Supplementing the educative in fluence of the schools are the public libraries, i5o in number in 1935.

Higher education is provided by Yale university (q.v.); by Trinity college (non-sectarian), at Hartford, founded in 1823; by Wesleyan university, at Middletown, the oldest college of the Methodist church in the United States, founded in 1831; by the Hartford theological seminary 0834); by the Connecticut State college (1881) at Storrs, which has an experimental station; by the Connecticut experiment station at New Haven, which was established in 1875 at Middletown and was the first in the United States; by normal schools at New Britain (established 1880, Willimantic (189o), New Haven 0894), and Danbury (1903) ; by Connecticut College for Women (19i I), at New London; and by a women's college, Albertus Magnus, Roman Catholic, at New Haven, opened in 1925. Graduate institutions include the Berk eley Divinity school, at New Haven, and Hartford Seminary f oundation.

Charities and Corrections.

A Commissioner of Welfare, assisted by an advisory Public Welfare Council, has supervision over all philanthropic and penal institutions. The institutions sup ported in whole or in part by the State are: a State prison at Wethersfield; ten county gaols; Connecticut reformatory, at Cheshire; Connecticut State farm for women, at Niantic; Con necticut school for boys, at Meriden; Long Lane farm for girls, at Middletown; House of the Good Shepherd, at Hartford; Florence Crittenton mission, at New Haven; the Connecticut State hospital at Middletown; the Norwich State hospital, at Norwich; the Fairfield State hospital, at Fairfield; Mansfield State training school and hospital (for feeble minded) ; the American school for the deaf, in Hartford; the oral school for the deaf, at Mystic; the Connecticut institute and industrial home for the blind, at Hart ford; the Newington home for crippled children; Fitch's Home for soldiers and sailors, at Norota Heights and Rocky Hill; a home for disabled soldiers under the direction of the Women's relief corps; five tuberculosis sanatoria for adults and one for children, 57 town alms-houses, eight county temporary homes for dependent and neglected children, and 33 public hospitals. Private institutions under the supervision of the State board include ten hospitals for the insane, 27 homes for the aged, and 24 Institutions for children. The greatest part of these institutions are supported by religious or benevolent organizations.

Industry, Trade and Transportation.

Connecticut is not an agricultural State. Although three-fourths of the land surface is included in farms, only 7% of this three-fourths is cultivated; but agriculture is of considerable economic and historic interest. The accounts of the fertility of the Connecticut valley were among the causes leading to the English colonization, and until the middle of the i9th century agriculture was the principal occu pation. In 193o, 29.6% of the population was classed as rural, though the actual farming population was somewhat smaller. In 193o the farms of the State numbered 17,195, a loss of 9,620 since 191o. The average value of land and buildings per acre in 1930 was $151.00 as compared with $33.03 in 19io. Tobacco is one of the most important agricultural products; the crop decreased from 28,110,453 lb. valued at $4,415,948 in 191o, to 14,276,000 lb., valued at $4,844,000 in 1934. From 192o-26 the average an nual production was in excess of 35,000,000 pounds. In the season of 1922 the Connecticut Valley Tobacco Association, a pool with a Connecticut membership of 2,400 growers farming 9o% of the acreage of outdoor tobacco in the State, was formed for the col lective marketing of the crop. The association sorts, packs, sweats and sells the leaf. Dairying is practised on more than four fifths of the farms of the State. The quality of the milk is being steadily improved through a system of inspection put into effect by the Milk Regulation board and administered by the Dairy and Food commission. The number of milch cows fluctuates around 120,00o. The production of milk increased from 45,749,849 gal. in 1909 to 68,788,285 gal. in 1934. In the same period the output of butter fell from 3,498,551 lb. to 6o3,3o3 lb. The poultry indus try increased very rapidly, owing to the favourable climate and the large market close at hand, there being produced in 1934 16,207, 875 doz. of chicken eggs. For the same reason market gardening increased the gardeners being organized into one State and 16 local organizations; the 1934 crop of farm garden vegetables was valued at $1,068,367. The values of five leading crops in 1934 were: hay, $6,25o,000, tobacco, $4,844,000; potatoes, $1,444,000; Indian corn, $1,834,000; and apples, $516,000.The mineral industries of Connecticut have had a declining fortune. The early settlers soon discovered metals and began to work them. About 1730 the production of iron became an impor tant industry in the vicinity of Salisbury, and from Connecticut iron many of the American military supplies in the Revolutionary War were manufactured. The quarries of granite near Long Island sound, those of sandstone at Portland, and of feldspar at Branchville and South Glastonbury, however, have furnished building and paving materials for other States. The total produc tion of mines and quarries of Connecticut in 1929 was valued at $3,810,000.

The fisheries are still a source of wealth but are not as impor tant as formerly. According to the U. S. bureau of fisheries, there were 1,16i persons and 7o vessels of all types engaged in the in dustry in 1933. The fisheries products of the State in that year were 9,878,o28 lb. and were valued at $613,130. The principal products, according to value, were market oysters, seed oysters, lobsters, flounders, and bluefish.

Manufacturing has encountered none of the vicissitudes of other industries. Indeed, manufacturing in Connecticut is notable for its early beginning and its development of certain branches beyond their development in other States. Iron products were manufactured throughout the i8th century, nails were made be fore 1716 and were exported from the colony, and it was in Con necticut that cannon were cast for the continental troops and the chains were made to block the channel of the Hudson river to British ships. Tinware was man ufactured in Berlin, Hartford county, as early as 1770, and tin, steel and iron goods were ped dled from Connecticut through the colonies. The Connecticut clock-maker and clock pedlar was the i8th century embodiment of Yankee ingenuity ; the most famous of the next generation of clock-makers were Eli Terry (1772-1859), who made a great success of his wooden clocks; Chauncy Jerome, who first used brass wheels in 1837 and founded in 1844 the works of the New Haven Clock company ; Gideon Roberts, and Terry's pupil and successor, Seth Thomas (1786-1859), who built the factory at Thomaston carried on by his son Seth Thomas (1816-88). In 1732 the London hatters complained of the competition of Con necticut hats in their trade. Before 1749 brass works were in operation at Waterbury—the great brass manufacturing business there growing out of the making of metal buttons. In 1768 paper mills were erected at Norwich, and in 1776 at East Hartford. In 1788 the first woollen mills in New England were established at Hartford, and about 1803 100 merino sheep were imported by David Humphreys, who in 18o6 built a mill in that part of Derby which is now Seymour and which was practically the first New England factory town; in 1812 steam was first used by the Mid dletown Woollen Manufacturing company. In 1804 the manufac ture of cotton was begun at Vernon, Hartford county; mills at Pomfret and Jewett City were established in 1806 and 1810 re spectively. Silk culture was successfully introduced about 1732; and there was a silk factory at Mansfield, Tolland county, in 1758. The period of greatest development of manufacturing began after the war of 1812. The decade of greatest relative development was that of 1909-19, during which the value of the products increased 184%. During the period 1850-1900, when the popula tion increased 145%, the average number of wage-earners em ployed in manufacturing establishments increased 248.3%, the number so employed constituting 13.7% of the State's total population in 185o and 19.5% of that in 1900. The average num ber of wage-earners in establishments conducted under the factory system in 1923 was 263,232, or 17.6% of the total population.

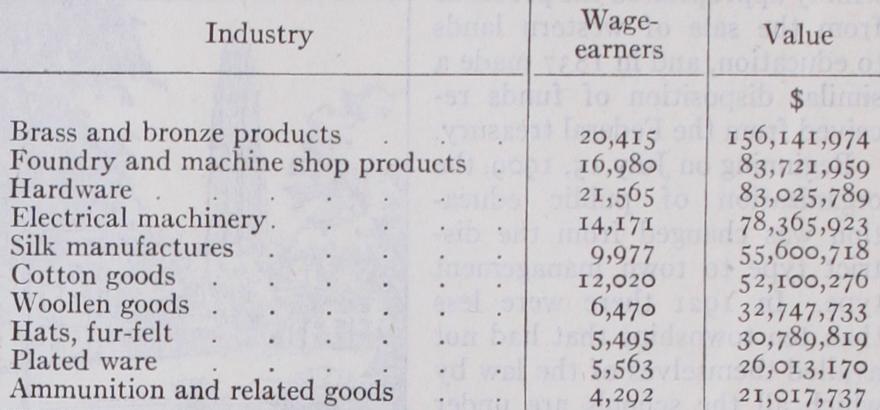

The World War brought a great volume of orders to Connecti cut factories and caused large numbers of plants to change the character of their products. In May 1918, 8o% of Connecticut's manufacturing was directly or indirectly engaged in producing munitions, rifles, machine guns, clothing and other articles used by the military forces, and there were five plants where ships and power boats were constructed. Wages were high during this pe riod. In the years of rapid expansion there were a great many strikes, and labour organizations increased in membership. During the two years following the armistice the factories began the proc ess of readjustment to peace-time conditions, which was com pleted by the depression of 1920-21. In 1922 the situation steadily improved; unemployment declined, and in Dec. 1922 the depart ment of labour reported an actual shortage of labour in the State. The growth of industry after 1922 was indicated by the fact that in 1923 and 1924 the cost of new factory construction and ad ditions was The 3,062 industrial establishments operating within the State in 1925 gave employment to 242,362 wage-earners, and had an output valued at $1,274,951,562. Connecticut's decrease in rank as a producer of textiles, especially cotton goods, was caused, in part, by industrial readjustments and, in part, by the increase in cotton manufacturing in the South. The leading manufacturing industries, the number of wage-earners employed and the values of their products in 1925 are shown in the table below.

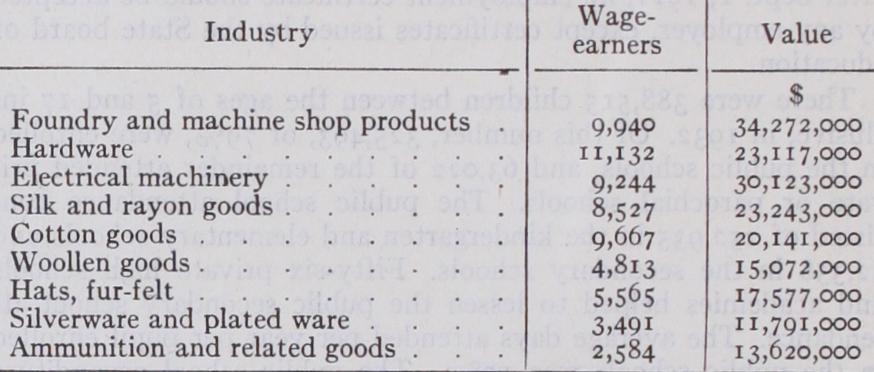

In 1933, when the depression was at its worst, the 2,410 indus trial establishments operating within the State gave employment to 183,322 wage-earners and had an output valued at $634,705,000. The following table, in comparison with that for 1925, is indica tive of the slump.

Transportation of products is facilitated by water routes (chiefly coastal), for which there are ports of entry at New Haven, Hartford, Stonington, New London, and Bridgeport, and of steam railways. One company, the New York, New Haven and Hartford, controls the greater part of this rail way mileage. Electric railways developed rapidly after 1895 until a maximum of 1,618m. was reached in 1922. The State highway system on Jan. I, 1934, was 2,206m., of which 2,156m. were sur faced. Motor vehicles registered in 1934 were 357,787.

History.

The first settlement by Europeans in Connecticut was made on the site of the present Hartford in 1633 by a party of Dutch from New Netherland. In the same year a trading post was established on the Connecticut river, near Windsor, by mem bers of the Plymouth colony, and John Oldham (1600-36) of Massachusetts explored the valley and made a good report of its resources. Encouraged by Oldham's account of the country, the inhabitants of three Massachusetts towns, Dorchester, Water town and New Town (now Cambridge) , left the colony for the Connecticut valley. The emigrants from Watertown founded Wethersfield in the winter of 1634-35; those from New Town settled at Windsor in the summer of 1635 ; and in the autumn of the same year people from Dorchester settled at Hartford. These early colonists had come to Massachusetts in the Puritan migra tion of 1630; their removal to Connecticut, in which they were led principally by Thomas Hooker (q.v.), Roger Ludlow (c. 1 S9o 1665) and John Haynes (d. 1654), was caused by their discontent with the autocratic character of the government in Massachusetts; but the instrument of government which they adopted in known as the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut, reveals no radical departure from the institutions of Massachusetts. The general court—the supreme civil authority—was composed of deputies from the towns and a governor and magistrate who were elected by the freemen of the towns. Its powers were not clearly defined; there was also no separation of the executive, legislative and judicial functions, and the authority of the governor was lim ited to that of a presiding officer. The government thus estab lished was not the product of a federation of townships as has often been stated; indeed, the townships had been governed dur ing the first year by commissioners deriving authority from Mas sachusetts, and the first general court was probably convened by them. In 1638 the celebrated Fundamental Orders were drawn up, and in 1639 they were adopted. Their most original feature was the omission of a religious test for citizenship, though a precedent for this is to be found in the Plymouth colony; on the other hand, the union of Church and State was presumed in the preamble, and in 1659 a property qualification (the possession of an estate of f30) for suffrage was imposed by the general court.In the meantime another migration to the Connecticut country had begun in 1638, when a party of Puritans who had arrived in Massachusetts the preceding year sailed from Boston for the Con necticut coast, and there founded New Haven. The leaders in this movement were John Davenport (1597-1670) and Theophilus Eaton, and their followers were drawn from the English middle class. Soon after their arrival these colonists drew up a "Planta tion Covenant" which made the Scriptures the supreme guide in civil as well as religious affairs; but no copy of this is now extant. In June 1639, however, a more definite statement of political principles was framed, in which it was clearly stated that the rules of Scripture should determine the ordering of the Church, the choice of magistrates, the making and repeal of laws, the dividing of inheritances, and all other matters of public import ; that only Church members could become free burgesses and officials of the colony; that the free burgesses should choose 12 men who should choose seven others, and that these should organize the Church and Civil Government. In 1643 the jurisdiction of the New Haven colony was extended by the admission of the townships of Milford, Guilford and Stamford to equal rights with New Haven, the rec ognition of their local governments and the formation of two courts for the whole jurisdiction—a court of magistrates to try im portant cases and hear appeals from "plantation" courts, and a general court with legislative powers, the highest court of appeals, which was similar in composition to the general court of the Con necticut colony. Two other townships were afterwards added to the colony—Southold, on Long Island, and Branford, Conn.

The religious test for citizenship was continued (except in the case of six citizens of Milford), and in 1644 the general court de cided that the "judicial laws of God as they were declared by Moses" should constitute a rule for all courts "till they be branched out into particulars hereafter." The theocratic character of the government thus established is clearly revealed in the series of strict enactments and decisions which constituted the famous "Blue Laws." Of the laws (45 in number) given by Samuel Peters in his General History of Connecticut, more than one-half really existed in New Haven, and more than four-fifths existed in some form in the New England colonies. Among those of New Haven are the prohibition of trial by jury, the infliction of the death penalty for adultery, and of the same penalty for conspir acy against the jurisdiction; the requirement of strict observance of the Sabbath, and heavy fines for "concealing or entertaining Quaker or other blasphemous heretics." A third Puritan settlement was established in 1635 at the mouth of the Connecticut river, under the auspices of an English com pany, whose leading members were William Fiennes, Lord Say and Sele (1582-1662 ), and Robert Greville, Lord Brooke In their honour the colony was named Saybrook. In 1636 George Fenwick (d. 1657), a member of the company, arrived, and as immigration from England soon afterwards greatly declined on account of the Puritan revolution, he sold the Saybrook colony to Connecticut in 1644. This early experiment in colonization at Saybrook and the sale by Fenwick are important on account of their relation to a fictitious land title. The Saye and Sele company secured in 1631 from Robert Rich, earl of Warwick (1587-1658), a quitclaim to his interest in the territory lying between the Nar ragansett river and the Pacific ocean. The nature of Warwick's right to the land is not stated in any extant document, and no title of his to it was ever shown. But the Connecticut authorities in their effort to establish a legal claim to the country and to thwart the efforts of the Hamilton family to assert its claims to the territory between the Connecticut river and the Narragansett bay—claims derived from a grant of the Plymouth Company to James, Marquess of Hamilton (1606-49) in 1635—elaborated the theory that the Plymouth Company had made a grant to War wick, and that consequently his quitclaim conferred jurisdiction upon the Saye and Sele company ; but even in this event Fenwick had no right to make his sale, for which he never secured confir mation.

The next step in the formation of modern Connecticut was the union of the New Haven colony with the older colony. This was accomplished by the royal charter of 1662, which defined the boundaries of Connecticut as extending from Massachusetts south to the seas and from Narragansett bay west to the South Sea (Pacific ocean). This charter had been secured without the knowledge or consent of the New Haven colonists, and they naturally protested against the union with Connecticut. But on account of the threatened absorption of a part of the Connecticut territory by the colony of New York, granted to the duke of York in 1664, and the news that a commission had been appointed in England to settle inter-colonial disputes, they finally assented to the Union in 1665. Hartford then became the capital of the united colonies, but shared that honour with New Haven from 1701 until 1873. The charter was liberal in its provisions. It created a cor poration under the name of the governor and company of the English colony of Connecticut in New England in America, sanc tioned the system of government already existing, provided that all acts of the general court should be valid upon being issued under the seal of the colony, and made no reservation of royal or parliamentary control over legislation or the administration of justice. Consequently there developed in Connecticut an inde pendent, self-reliant colonial government which looked to its chartered privileges as the supreme source of authority.

Although the governmental and religious influences which moulded Connecticut were similar to those which moulded New England at large, the colony developed certain distinctive charac teristics. Its policy was "to avoid notoriety and public attitudes; to secure privileges without attracting needless notice ; to act as intensely and vigourously as possible when action seemed neces sary and promising; but to say as little as possible, and evade as much as possible when open resistance was evident folly." The relations of Connecticut with the neighbouring colonies were notable for numerous and continuous quarrels in the 17th century. Soon after the first settlements were made a dispute arose with Massachusetts regarding the boundary between the two colonies ; after the brief war with the Pequot Indians in 1637 a similar quarrel followed regarding Connecticut's right to the Pequot lands; and in the New England Confederation (estab lished in 1643) friction between Massachusetts and Connecticut continued. Difficulty with Rhode Island was caused by the con flict between the colony's charter and the Connecticut charter regarding the western boundary of Rhode Island ; and the en croachment of outlying Connecticut settlements on Dutch terri tory, and the attempt to extend the boundaries of New York to the Connecticut river, gave rise to other disputes. These questions of boundary were a source of continuous discord, the last of them not being settled until 188r. The attempts of governors Joseph Dudley (1647-17 2o), of Massachusetts, and Thomas Dongan (1634-1715), of New York, to unite Connecticut with their colonies also caused difficulty. The relations of Connecticut and New Haven with the mother country were similar to those of the other New England colonies. The period of most serious friction was that during the administration of the New England colonies by Sir Edmund Andros (q.v.), who in pursuance of the later Stuart policy both in England and in her American colonies visited Hartford on Oct. 31, 1687, to execute quo warranto proceedings against the charter of 1662. It is said that in the course of a discussion at night over the surrender of the charter the candles were extinguished, and the document itself (which had been brought to the meeting) was removed from the table where it had been placed. According to tradition it was hidden in a large oak tree, afterwards known as the "Charter Oak." But though Andros thus failed to secure the charter, he dissolved the existing government. After the Revolution of 1686, however, government under the charter was resumed, and the Crown lawyers decided that the charter had not been invalidated by the quo warranto proceedings.

Religious affairs formed one of the most important problems in the life of the colony. The established ecclesiastical system was the Congregational. The code of 165o (Connecticut) taxed all persons for its support, provided for the collection of church taxes by civil distraint if necessary, and forbade the formation of new churches without the consent of the general court. The New Halfway Covenant of 1657, which extended Church member ship so as to include all baptized persons, was sanctioned by the general court in 1664. The custom by which neighbouring churches sought mutual aid and advice prepared the way for the Presby terian system of Church government, which was established by an ecclesiastical assembly held at Saybrook in 1708, the Church constitution there framed being known as the "Saybrook Plat form." At that time, however, a liberal policy towards dissent was adopted, the general court granting permission for churches "soberly to differ or dissent" from the establishment. Hence a large number of new churches soon sprang into being. In 2 7 the court forbade any ordained minister to enter another parish than his own without an invitation and decided that only those were legal ministers who were recognized as such by the general court. Throughout the remaining years of the i8th century there was constant friction between the establishment and the non conforming churches; but in 1791 the right of free incorporation was granted to all sects.

In the Revolutionary War Connecticut took a prominent part. At the time of the controversy over the Stamp Act the general court instructed the colony's agent in London to insist on "the exclusive right of the colonists to tax themselves, and on the privilege of trial by jury," as rights that could not be surrendered. The patriot sentiment was so strong that loyalists from other colonies were sent to Connecticut, where it was believed they would have no influence ; the copper mines at Simsbury were converted into a military prison ; but among the nonconforming sects, on the other hand, there was considerable sympathy for the British cause. Preparations for war were made in 17 74 ; on April 28, 1775, the expedition against Ticonderoga and Crown Point was resolved upon by some of the leading members of the Connecticut assembly; and although they had acted in their private capacity, funds were obtained from the colonial treasury to raise the force which on May 8 was put under the command of Ethan Allen. Connecticut volunteers were among the first to go to Boston after the battle of Lexington, and more than one half of Washington's army at New York in 1776 was composed of Connecticut soldiers. Yet with the exception of isolated British movements against Stonington in 1775, Danbury in 1777, New Haven in 1779 and New London in 1781, no battles were fought in Connecticut territory.

In 1776 the government of Connecticut was reorganized as a State, the charter of 1662 being adopted by the general court as "the Civil Constitution of this State, under the sole authority of the people thereof, independent of any king or prince whatever." In the formation of the General Government the policy of the State was national. It acquiesced in the loss of western lands through a decision (1782) of a court appointed by the Con federation (see WYOMING VALLEY) ; favoured the levy of taxes on imports by Federal authority; relinquished (1786) its claims to all remaining western lands, except the Western Reserve (see OHIO) ; and in the Constitutional Convention of 1787 the present system of national representation in Congress was proposed by the Connecticut delegates as a compromise between the plans presented by Virginia and those presented by New Jersey.

For many years the Federalist party controlled the affairs of the State. The opposition to the growth of American nationality which characterized the later years of that party found expression in a resolution of the general assembly that a bill for incorporating State troops in the Federal army would be "utterly subversive of the rights and liberties of the people of the State, and the freedom, sovereignty and independence of the same," and in the prominent part taken by Connecticut in the Hartford Convention (see HARTFORD) and in the advocacy of the radical amendments proposed by it. But the development of manufactures, • the dis content of nonconforming religious sects with the establishment, and the confusion of the executive, legislative and judicial branches of government in the constitution opened the way for a political revolution. All the discontented elements united with the Democratic Party in 1817 and defeated the Federalists in the State election; and in 1818 the existing constitution was adopted. From 183o until 1855 there was close rivalry between the Demo cratic and Whig Parties for control of the State administra tion.

In the Civil War Connecticut was one of the most ardent sup porters of the Union cause. When President Lincoln issued his first call, for 75,00o volunteers, there was not a single militia company in the State ready for service. Gov. William A. Buck ingham 5) , one of the ablest and most zealous of the "war governors," and afterwards, from 1869 until his death, a member of the United States Senate, issued a call for volunteers in April 1861 ; and soon 54 companies, more than five times the State's quota, were organized. Corporations, individuals and towns made liberal contributions of money. The general assembly made an appropriation of $2,000,000, and the State furnished approxi mately 48,00o men to the army. Equally important was the moral support given to the Federal government by the people. After the war the Republicans were more frequently successful at the polls than the Democrats. Representation in the lower house of the general assembly, by the constitution of 1818, was based on the townships, each township having two representatives, except townships created after 1818, which had only one each. This method constituted a serious evil when, in the transition from agriculture to manufacturing as the leading industry, the popula tion became concentrated to a considerable degree in a few large cities and the relative importance of the various townships was greatly changed. The township of Marlborough, with a population in 1900 of 322, then had one representative, while the city of Hartford, with a population of 79,85o, had only two; and the township of Union, with 428 inhabitants, and the city of New Haven, with 108,027, each had two representatives. The appor tionment of representation in the State senate had become almost as objectionable. By a constitutional amendment of 1828 it had been provided that senators should be chosen by districts, and that in the apportionment regard should be had to population, no county or township to be divided and no part of one county to be joined to the whole or part of another county, and each county to have at least two senators; but by 190o any relation that the districts might once have had to population had dis appeared. The system of representation had sometimes put in power a political party representing a minority of the voters : in 1878, 1884, 1886, 1888 and 1890 the Democratic candidates for State executive offices received a plurality vote; but, as a majority was not obtained, these elections were referred to the general assembly, and the Republican Party, in control of the lower house, secured the election of its candidates; in 1901 constitutional amendments were adopted making a plurality vote sufficient for election, increasing the number of senatorial districts, and stipu lating that "in forming them regard shall be had" to population.

The question of calling a constitutional convention, for which the present constitution makes no provision, was submitted to the people in i9o1 and was carried. But the act providing for the convention had stipulated that the delegates thereto should be chosen on the basis of township representation instead of popula tion. The small townships thus secured practical control of the convention, and no radical changes were made. A compromise amendment submitted by the convention, providing for two repre sentatives for each township or 2,000 inhabitants, and one more for each 5,000 above 5o,000, satisfied neither side, and when submitted to a popular vote, on June 16, 19o2, was overwhelm ingly defeated. The state added several amendments to its con stitution, notably that of 1924 granting the governor power to veto specific sections of appropriation bills, but refused to ratify the national income tax, prohibition, and proposed child labour amendments and only tardily indorsed woman's suffrage. A work men's compensation law was adopted in 1914, but Connecticut's chief claim to rank among the more humane states rested upon her eleemosynary' institutions. In 1931 the State broke another tradition by legalizing Sunday baseball. The financial crisis in 1933 forced a grant to the governor of extraordinary authority over the banks but failed to prompt an appropriation sufficient to match the desired Federal allotment of $4,000,000 for relief. Dis content found expression in the election of a socialist mayor in Bridgeport and of several of that party to the legislature. Popular attention focused on the State's tercentenary in 1935. Despite a swing away from the New Deal in 1935 President Roosevelt carried Connecticut in the 1936 election.