Connective Tissues

CONNECTIVE TISSUES, in anatomy, the intercellular, supporting substances found in the tissues and organs of the animal body. They comprise the following types : areolar tissue, adipose tissue, reticular or lymphoid tissue, white fibrous tissue, elastic tissue, cartilage and bone. They are all developed from the same layer of embryonic cells and according to the nature of their work the ground substance varies in its texture, being fibrous in some, calcareous and rigid in others.

Areolar Tissue.

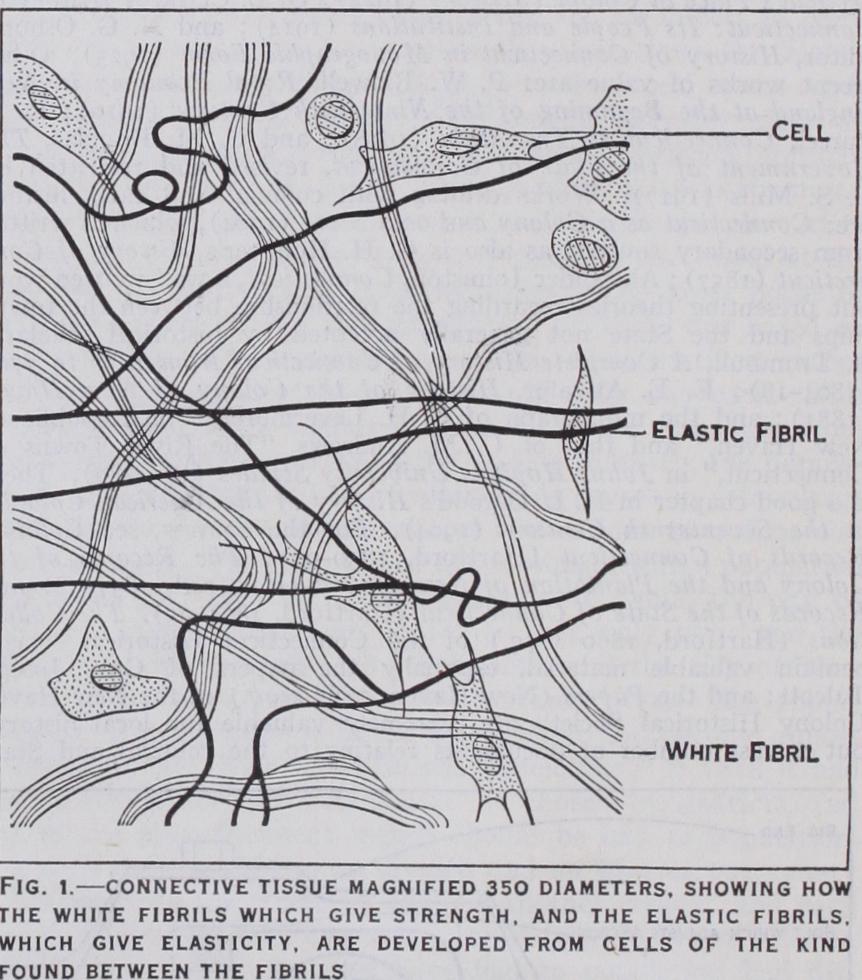

This is found in its most typical form uniting the skin to the deeper lying parts. It varies greatly in density according to the animal and the position of the body from which it is taken. A piece of the looser variety, microscopically, consists of bundles of fine white fibres (fig. i) running in all directions and interlacing with one another to form a meshwork with inter vening spaces. The bundles vary much in size, but the fibres of which they are composed are very uniform. A bundle may branch by sending fibres to unite with similar branches from neighbour ing bundles, but the individual fibres neither branch nor fuse with one another. They are arranged parallel to one another, and in the bundles are bound together by a cement substance. The mesh work formed by these bundles is filled by a ground substance con taining mucin. In this ground substance lie the cells of the tissue. In addition to the white fibres a second variety of fibres (yellow elastic fibres) is present in this tissue. They can be readily dis tinguished by their larger and variable size, by their more distinct outline, and by the fact that they, for the most part, run as straight lines through the preparation. Moreover they frequently branch, and the branches unite with those of neighbouring fibres. Several of these will be found torn across in any preparation especially at the edges, and the torn ends are curled up in a very characteristic manner. The two types of fibre further differ from one another both chemically and physically. Thus the white fibre swells up and dissolves in boiling water, yielding a solution of gelatin, whereas the yellow elastic fibre is quite insoluble under these conditions. The white fibres swell when treated with weak acetic acid, and are readily dissolved by peptic digestion but not by pancreatic. The yellow elastic fibres, on the other hand, are unaffected by acetic acid and resist the action of gastric juice for a long time, but are dissolved by pancreatic juice. Physically, the white fibres are inextensible and extraordinarily strong, being able, weight for weight, to carry a greater strain than steel wire. The yellow elastic fibres, on the other are easily extensible and very elastic, but are far less strong than the white fibres.Several types of cells are found in this tissue and may be classi fied as: (I) Lamellar cells, i.e., flattened branching cells, usually attached to the bundles of white fibres or at the junction of two or more bundles. The branches commonly unite with similar branches of neighbouring cells. (2) Plasma cells. These have peculiar staining reactions, are small and, in the main, spherical. (3) Granular cells: spherical cells densely packed with granules which stain deeply with basic dyes. (4) Leucocytes: blood cor puscles which have left the capillaries. They vary in number and variety.

Adipose or Fatty Tissue.

This is formed from areolar tissue by an accumulation of fat within certain of the cells of the tissue, especially the granular cells, though some regard fat cells as specific, and to be found in large numbers only in certain parts of the body. The fat is either taken in as such by the cell, or, more commonly is manufactured by the cell from other chemical material (carbohydrate chiefly) and deposited within it as small granules. As these accumulate they run together, and this process continuing, the cell at last becomes converted into a thin layer of living material surrounding a single large fat globule. The use of fatty tissue is as a storehouse of food. Hence, it is found where it will not interfere with the work ing of the tissues and organs, and in several positions as packing to fill up irregular spaces, e.g., between the eyeball and the bony socket of the eye.

Reticular Tissue.

Here, the reticulum of white fibres is built up of very fine strands leaving large interspaces in which the cells typical of the tissue are enclosed. The ground substance is reduced to a mini mum. Many connective tissue and endo thelial cells lie on the fibres which may in places be completely covered by them. Such a general scaffolding may be demon strated in lymphatic glands, the spleen, liver and other cellular organs.

White Fibrous Tissue.

In this tissue the white fibres largely preponderate. It is f ound wherever great strength combined with flexibility is required and the fibres are arranged in the direction in which the stress has to be transmitted. The fibrous bundles may be parallel as in a tendon, or united to form a membrane. Such are the ligaments around the joints or the fasciae covering the muscles of the limbs, etc. In other positions, e.g. the dura mater, the fibrous bundles course in all directions, and f orm a very tough membrane. The cells of such tissues lie in the spaces between the bundles and are flattened in two or three directions where they are compressed by the oval fibrous bundles surrounding them (figs. 2 and 3). The cells thus lie in linear groups parallel to the bundles, presenting a char acteristic appearance when examined under the microscope. Yellow Elastic Tissue.—This is mainly composed of elastic fibres. It is found where a contin uous but varying stress has to be supported. In some positions the elastic tissue consists of branching fibres arranged parallel to one another and bound to gether by white fibres, e.g., liga mentum nuchae (fig. 4). In other cases it forms thin plates per f orated in many directions and produces a fenestrated mem brane. Such plates are arranged round the larger arteries forming a large proportion of the artery wall. All the connective tissues carry a small number of blood vessels and are supplied with lymphatics and nerves.

Cartilage.

Cartilage or gristle is a tough and dense tissue with a certain degree of flexibility and high elasticity. It is found where flexibility is required but a fixed shape must be retained, e.g. the trachea and the external ear or pinna. It is largely asso ciated with the bones in the formation of the skeleton. The tissue consists of cells embedded in a solid matrix or ground substance.Three varieties are distinguished according to the nature of the matrix: hyaline, white fibro-cartilage and elastic cartilage. In the first the matrix is homogeneous, in the others the corresponding type of fibrous tissue is present.

Hyaline Cartilage

(fig. 5).—In this variety the cells are rounded, have an oval nucleus and a granular, often vacuolated cell-body. Their number varies in different specimens, being, roughly, in inverse ratio to the age of the tissue. Cartilage grows by deposition of new matrix by the cartilage cells which thus become more and more separated from one other. They are of ten to be seen in groups of two, three or four cells, indicating the common origin of each group from a parent cell. Towards the surface of the cartilage they tend to become flattened in a direc tion parallel to the surface. Some of them near the surface of a piece of cartilage may be branched, appearing as a transition form between connective tissue corpuscles and typical cartilage cells.This is particularly the case at points where tendons or ligaments are attached. Lime salts are often deposited in the matrix of hyaline cartilage especially in old animals or in the deeper layers of articular cartilage where it is attached to bone. Such a deposit is well marked in the superficial parts of the skeleton of the carti laginous fishes. In the develop ment of vertebrata, the skeleton is first laid down as hyaline cartilage which is gradually removed, bone being deposited in its place. In the adult, hyaline cartilage is found at the ends of the long bones (articular cartilage), uniting the bony ribs to the sternum (costal cartilage), and forming the cartilages of the nose, trachea and bronchi, etc. All forms of cartilage are non-vascular so that the cells must obtain food and get rid of waste products by dif fusion through the matrix.

White Fibro-Cartilage.—In this variety, white fibres ramify through the matrix (fig. 6). The cells lie separate and not in groups, and the amount of matrix between commonly is small. The white fibres may run in all di rections or, chiefly, in one direc tion only. Owing to the presence of much fibrous tissue this variety of cartilage is tougher than hyaline cartilage and less flexible. It is found in places which have to withstand great compression but where a less rigid structure than bone is demanded. Thus it forms the intervertebral discs, the interarticular cartilages, or the edges of joint surfaces to deepen the surface.

Elastic Fibro-Cartilage.—In this variety the matrix is per meated by a complex and well defined meshwork of elastic fibres (fig. 7). The size of the fibres varies much in different speci mens. It is found in parts where flexibility and permanence of shape are requisite, as in the pinna of the ear, the epiglottis, etc.

Bone.

In bone, mineral salts are deposited in the intercellular matrix. If bone be incinerated so that the organic matter is burnt away, a residue is left which consists chiefly of calcium phosphate, and amounts to as much as two-thirds of the weight of the original bone. If, on the other hand, bone be macerated in hydrochloric or nitric acid the calcium phosphate is dissolved, leaving the organic matter practically unaffected and still showing the microscopic structure of bone. Hence it follows that the organic matrix is uniformly impregnated with the calcium salts. According to its naked-eye appearance bone is distinguished as compact or cancel lated. The former is dense like ivory and forms the outer surface of all bones. The whole of the shaft of a long bone is composed of this compact form. Cancellated bone has a spongy structure and contains large interspaces filled with a fatty tissue rich in blood vessels. This variety forms the interior of most bones, especially the heads of the long bones, the interior of the ribs, etc. The cavity of the shaft of a long bone is filled, as are the smaller cavities in cancellated bone, with bone marrow (see below).The minute structure of bone may be seen in a piece of dried bone which has been ground down until sufficiently thin for micro scopic purposes. In a thin transverse slice of a long bone are seen (fig. 8) a number of circular units bound into a compact whole by intervening material showing in the main the same structural de tails. Each of these units is an Haversian system. Centrally, there is a dark area, the Haver sian canal, around which the bone matrix is deposited as concentric laminae. Between the laminae are the bone lacunae and spread ing away from them in directions generally transverse to the lami nae are fine branching lines—the canaliculi. All dark parts of the specimen are natural spaces filled with debris during preparation. In the living bone the Haversian canal contains an artery and vein, some capillaries, a flattened lymph space, fine medullated nerve fibres—the whole being sup ported in a fine fatty tissue. Each lacuna is filled with a cell (the bone corpuscle) and the canaliculi contain fine branching proc esses of these cells. On comparing such a section with one taken parallel to the long axis of the shaft of a bone it is seen that the Haversian canals run some distance along the length of the bone, and frequently unite with one another or communicate by obliquely coursing channels. The spaces between the Haversian systems are filled in with further bony tissue which may or may not be arranged in laminae. Cancellous bone only differs from compact bone in the arrangement of the bone tissue. This en closes a number of irregular, communicating spaces strengthened in places by parallel trabeculae that run in the direction in which the bone has to support its maximum strain. Usually the bone trabeculae are so fine that they do not contain Haversian systems, but they include bone corpuscles.

Bone Marrow.

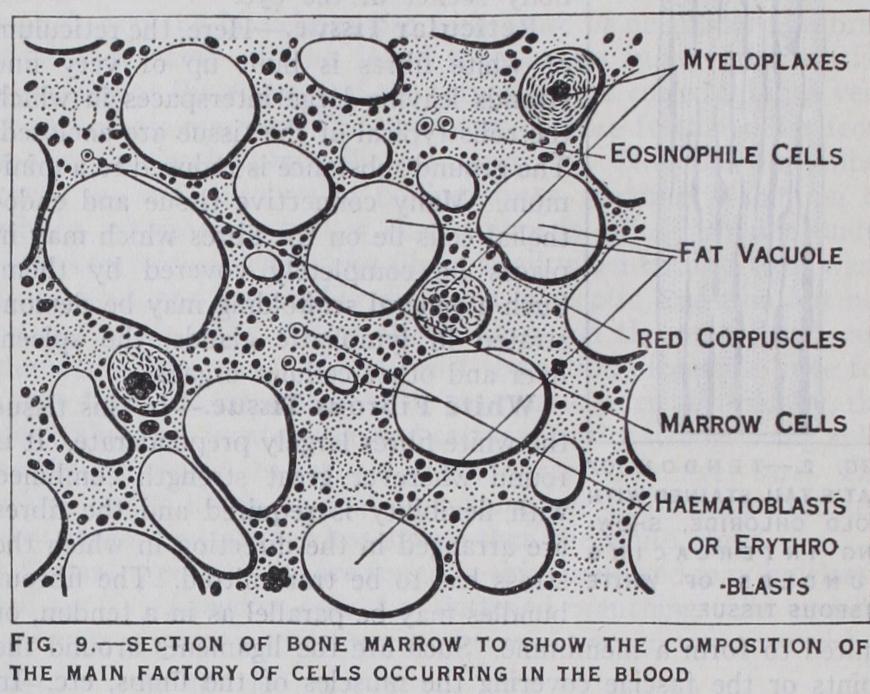

This fills the central cavity of tubular bones and the cavities of spongy bone tissue. It is largely composed of fat cells and is red or yellow in colour. Red marrow consists of fat cells lying in a tissue made up of large and small marrow cells and giant cells or myeloplaxes (fig. 9). The whole of these elements are supported in a delicate connective tissue. Some of the marrow cells are typical leucocytes and lymphocytes as found in circulating blood. Others (myelocytes) are larger than leu cocytes, with round or oval nuclei, and a protoplasm containing small or large granules. These different types of cell probably develop into leucocytes. The giant cells are large spherical cells with several nuclei. In addition to fully developed red blood corpuscles there are also present numerous young nucleated red blood cells (erythroblasts or haematoblasts).

Development of Bone.

New bone is formed from a vascular fibrous membrane, either directly, or with interpolation of a carti laginous stage. The development of bone from cartilage is the more complicated of the two because in it bone formation is taking place in two positions at the same time and in two rather different manners. Thus bone is being laid down from the outside by the fibrous membrane surrounding the cartilage, (perichon drium) and also within the substance of the cartilage (endochon dral formation) . Perichondral formation takes place somewhat earlier than endochondral, and in a long bone is first seen around the centre of the shaft, i.e. in that portion of the bone which forms the diaphysis. Here the perichondrium is vascular and car ries on the surface next to the cartilage an almost continuous layer of cuboid cells, the osteoblasts. Calcium salts are deposited in the matrix of the immediately subjacent cartilage and the cell spaces of the cartilage increase in size while the cartilage cells shrink. Further growth of cartilage ceases in this region so that at one time the shaft of the cartilage may appear constricted in the middle. The formation of bone endochondrally is ushered in by the ingrowth of blood vessels from the perichondrium. A way through the calcified matrix of the cartilage is eroded by poly nucleated giant cells, the osteoclasts, which apply themselves to the matrix and gradually dissolve it away. The enlarged cartilage spaces are thus opened to one another, and soon the only remnants of the matrix consist of irregular calcified trabeculae. In this way the primary marrow spaces are produced, the whole structure representing the future spongy portion of the bone. The next step in both perichondral and endochondral bone formation con sists in the deposition of bone matrix by the osteoblasts. In the spongy portion they deposit a layer upon the surfaces of the calcified cartilage matrix, and thus in newly formed bone we find a central framework of cartilage enclosed in a layer of bone (see fig. ro) . In the perichondral formation the deposition is effected in the same manner but is not uniformly spread over the whole surface, trabeculae being formed. These become confluent at places, thus leaving spaces through which blood vessels and osteo genetic tissue pass to reach the interior of the bone. As the de position of bone matrix proceeds, some of the osteoblasts become included within the matrix, and ceasing to form fresh matrix become bone corpuscles. Increase in thickness of the new bone is effected by the deposition of fresh matrix followed again by the inclusion of further osteoblasts. The spaces within the trabeculae become in this way gradually narrowed by the deposition of matrix until at last a centre is left only large enough to contain the blood vessels and their accompanying nerves, lymphatics and a small number of osteoblasts. Bone formation then ceases. In this manner the Haversian systems are produced.

Growth of the bone proceeds by deposition of more matrix on the exterior, but absorption is also taking place. This is most typically seen within the spongy portion. The absorption of the trabeculae is effected by the os teoblasts. These become applied to the trabeculae and gradually eat their way into the matrix thus coming to lie within lacunae.

They possess the power of dis solving both bone and cartilage matrix. Side by side with this solution process we may often see new formation taking place by the activity of the osteoblasts (fig. Io). In this manner the whole framework of the bone may be gradually replaced. The process is most active in em bryos and very young animals, but also continues during the whole life of an animal, thus ef fecting alterations in shape and structure of the whole bone.

Growth in the length of a bone is effected by formation of new bone at either end of the shaft.

After the ossification centre has been formed in the shaft (dia physis) of the bone subsidiary centres make their appearance in the heads of the bones. These form, by a similar process of bone formation, fresh bone masses which, however, are not continuous with the bone tissue of the shaft. They form the epiphyses. They are attached to the dia physis by an intermediate piece of cartilage, and it is by a process of growth of this cartilage and its subsequent replacement by bone that growth in length of the whole bone is effected (fig. Io). This piece of intervening cartilage can be easily seen in a young bone and persists as long as the bone can increase in length. Thus in man the last junction of epiphysis to diaphysis may not take place until the 28th year.

Development of bone in membrane shows a course in all respects very similar to perichondral bone formation. A layer of osteogenetic tissue makes its appearance in the membrane from which the bone is to be formed. In this tissue a number of stiff fibres are deposited which soon become covered and impregnated with calcium salts. Around these bundles of fibres numbers of osteoblasts are deposited and by them bone matrix is deposited in irregular trabeculae. The bone increases by the deposition of fresh matrix just as in perichondral bone formation and Haversian systems are formed after precisely the same manner.