Constantinople

CONSTANTINOPLE, Turkey, now called Istanbul, for merly the capital of the Turkish empire, situated in 41° o' 16" N. and 28° 58' 14" E. The city stands at the southern extremity of the Bosporus, upon a hilly promontory that runs out from the European side of the straits towards the Asiatic bank. The sea of Marmora is on the south, and the bay of the Bosporus, forming the magnificent harbour of the Golden Horn, some 4 m. long, on the north. Two streams, the ancient Cydaris and Barbysus, now Ali-Bey-Su and Kiahat-Hane-Su, enter the bay at its north-western end. A small winter stream, the Lycus, flowing through the prom ontory west to south-east into the Sea of Marmora, separates a long ridge, divided by cross-valleys into six eminences, over hanging the Golden Horn, from a large isolated hill in the south west. Hence the claim of Constantinople to be enthroned, like Rome, upon seven hills. The first hill has the Seraglio, St. Sophia and the Hippodrome; the second the column of Constantine and the mosque Nuri-Osmanieh; the third the war office, the Seraskereate tower and the mosque of Sultan Suleiman; the fourth the mosque of Sultan Mohammed II., the Conqueror; the fifth the mosque of Sultan Selim; the sixth Tekfour Serai and the quarter of Egri Kapu; the seventh Avret Tash and the quarter of Psamatia. In Byzantine times the two last hills were named respectively the hill of Blachernae and the Xerolophos or dry hill.

Origin and Site.—Constantinople is famous in history, in the first place as the capital of the Roman empire in the East for more than eleven centuries (330-1453), and in the second as the capital of the Ottoman empire which followed. In respect of influence over the course of human affairs, its only rivals are Athens, Rome and Jerusalem. Yet even the gifts of these rivals to the cause of civilization often bear the image and superscrip tion of Constantinople upon them. Roman law, Greek literature, the theology of the Christian church, for example, are intimately associated with the history of Constantinople.

The city was founded by Constantine the Great, through the enlargement of the old town of Byzantium (q.v.) in A.D. 328, and was inaugurated as a new seat of government on May r, A.D.

33o. To indicate its political dignity, it was named New Rome, while to perpetuate the fame of its founder it was styled Con– stantinople. The chief patriarch of the Greek church still signs himself "archbishop of Constantinople, New Rome." The old name of the place, Byzantium, however, continued in use.

The creation of a new capital by Constantine was not an act of personal caprice or individual judgment. It was the result of causes long in operation, and had been foreshadowed, 4o years before, in the policy of Diocletian. After the senate and people of Rome had ceased to be the sovereigns of the Roman world, and their authority had been vested in the sole person of the em peror, the eternal city could no longer claim to be the rightful throne of the state. That honour could henceforth be conferred upon any place in the Roman world which might suit the con venience of the emperor, or serve more efficiently the interests he had to guard. Furthermore, the empire was now upon its defence. Dreams of conquests and extension had long been abandoned, and the pressing question of the time was how to repel the persistent assaults of Persia and the barbarians upon the frontiers of the realm, and so retain the dominion inherited from the valour of the past. The size of the empire made it difficult, if not impossible, to attend to these assaults, or to control the ambition of successful generals, from one centre. Further, the East had grown in political importance, both as the scene of the most active life in the state and as the portion of the empire most exposed to attack. Hence the famous scheme of Diocletian to divide the burden of govern ment between four colleagues, in order to secure a better adminis tration of civil and of military affairs. It was a scheme, however, that lowered the prestige of Rome, for it involved four distinct seats of government, among which, as the event proved, no place was found for the ancient capital of the Roman world. It also de clared the high position of the East, by the selection of Nicomedia in Asia Minor as the residence of Diocletian himself. When Con stantine, therefore, established a new seat of government at By zantium, he adopted a policy inaugurated before his day as essen tial to the preservation of the Roman dominion. He can claim originality only in his choice of the particular point at which that seat was placed, and in his recognition of the fact that his alliance with the Christian church could be best maintained in a new atmosphere.

But whatever view may be taken of the policy which divided the government of the empire, these can be no dispute as to the wisdom displayed in the selection of the site for a new imperial throne. Situated where Europe and Asia are parted by a channel never more than 5 m. across, and sometimes less than half a mile wide, placed at a point commanding the great waterway between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, the position affords im mense scope for commercial enterprise and political action in rich and varied regions of the world. Moreover, the site constituted a natural citadel, difficult to approach or to invest, and an almost impregnable refuge in the hour of defeat, within which broken forces might rally to retrieve disaster. To surround it, an enemy required to be strong upon both land and sea. Foes advancing through Asia Minor would have their march arrested, and their blows kept beyond striking distance, by the moat which the waters of the Bosporus, the Sea of Marmora and the Dardanelles combine to form. The narrow straits in which the waterway connecting the Mediterranean with the Black Sea contracts, both to the north and to the south of the city, could be rendered impassable to hostile fleets approaching from either direction, while on the landward side the line of defence was so short that it could be strongly forti fied, and held against large numbers by a comparatively small force. Nature, indeed, cannot relieve men of their duty to be wise and brave, but, in the marvellous configuration of land and sea about Constantinople, nature has done her utmost to enable human skill and courage to establish there the splendid and stable throne of a great empire.

Architecture and

Antiquities.—Byzantium, out of which Constantinople sprang, occupied most of the land comprised in the two hills nearest the head of the promontory, and the level ground at their base. The landward wall started from a point near the present Stamboul custom-house, and reached the ridge of the second hill, a little to the east of the point marked by Chemberli Tash (the column of Constantine). There the principal gate of the town opened upon the Egnatian road. From that gate the wall descended towards the Sea of Marmora, touching the water in the neighbourhood of the Seraglio lighthouse. The Acropolis, enclosing venerated temples, crowned the summit of the first hill, where the Seraglio stands. Immediately to the south of the fortress was the principal market-place of the town, surrounded by porticoes on its four sides, and hence named the Tetrastoon. On the southern side of the square stood the baths of Zeuxippus, and beyond them, still farther south, lay the Hip podrome, which Septimius Severus had undertaken to build but failed to complete. Two theatres, on the eastern slope of the Acropolis, faced the bright waters of the Marmora, and a stadium was found on the level tract on the other side of the hill, close to the Golden Horn. The Strategion, devoted to the military exer cises of the brave little town, stood close to Sirkedji Iskelessi, and two artificial harbours, the Portus Prosforianus and the Neorion, indented the shore of the Golden Horn. A graceful granite column, still erect on the slope above the head of the promontory, com memorated the victory of Claudius Gothicus over the Goths at Nissa, A.D. 269. All this furniture of Byzantium was appropriated for the use of the new capital.According to Zosimus, the line of the landward walls erected by Constantine to defend New Rome was drawn at a distance of nearly 2 m. (r 5 stadia) to the west of the limits of the old town. It therefore ran across the promontory from the vicinity of Un Kapan Kapusi (Porta Platea), at the Stamboul head of the Inner Bridge, to the neighbourhood of Daud Pasha Kapusi (Porta S. Aemiliani), on the Marmora, and thus added the third and fourth hills and portions of the fifth and seventh hills to the territory of Byzantium. We have two indications of the course of these walls on the seventh hill. One is found in the name Isa Kapusi (the gate of Jesus) attached to a mosque, formerly a Christian church, situated above the quarter of Psamatia. It per petuates the memory of the beautiful gateway which formed the triumphal entrance into the city of Constantine, and which sur vived the original bounds of the new capital as late as 15°8, when it was overthrown by an earthquake. The other indication is the name Alti Mermer (the six columns) given to a quarter in the same neighbourhood. The name is an ignorant translation of Exa kionion, the corrupt form of the designation Exokionion, which belonged in Byzantine days to that quarter because marked by a column outside the city limits. Hence the Arians, upon their expulsion from the city by Theodosius I., were allowed to hold their religious services in the Exokionion, seeing that it was an extra-mural district. This explains the fact that Arians are some times styled Exokionitae by ecclesiastical historians. The Con stantinian line of fortifications, therefore, ran a little to the east of the quarter of Alti Mermer. In addition to the territory en closed within the limits just described, the suburb of Sycae or Galata, on the opposite side of the Golden Horn, and the suburb of Blachernae, on the sixth hill, were regarded as parts of the city, but stood within their own fortifications. It was to the ram parts of Constantine that the city owed its deliverance when attacked by the Goths, after the terrible defeat of Valens at Adrianople, A.D. 378.

Fortifications Against Barbarism.—To his courtiers. the bounds assigned to New Rome by Constantine seemed too wide, but after 8o years they were too narrow for the population that had gathered within the city. The barbarians had meantime also grown more formidable, and this made it necessary to have stronger fortifications for the capital. Accordingly, in 413, in the reign of Theodosius II., Anthemius, then praetorian prefect of the East and regent, enlarged and ref ortified the city by the erection of the wall which forms the innermost line of defence in the bulwarks . whose picturesque ruins now stretch from the Sea ' of Marmora, on the south of Yedi Kuleh (the seven towers), northwards to the old Byzantine palace of the Porphyrogenitus (Tekf our Serai), above the quarter of Egri Kapu. There the new works joined the walls of the suburb of Blachernae, and thus protected the city on the west down to the Golden Horn. Some what later, in 439, the walls along the Marmora and the Golden Horn were brought, by the prefect Cyrus, up to the extremities of the new landward walls, and thus invested the capital in com plete armour. Then also Constantinople attained its final size. For any subsequent extension of the city limits was insignificant, and was due to strategic considerations. In 447 the wall of Anthemius was seriously injured by one of those earthquakes to which the city is liable. The disaster was all the more grave, as the Huns under Attila were carrying everything before them in the Balkan lands. The desperateness of the situation, however, roused the government of Theodosius II., who was still upon the throne, to put forth the most energetic efforts to meet the emer gency. If we may trust two contemporary inscriptions, one Latin, the other Greek, still found on the gate Yeni Mevlevi Khaneh Kapusi (Porta Rhegium), the capital was again fully armed, and rendered more secure than ever, by the prefect Constantine, in less than two months. Not only was the wall of Anthemius restored, but, at the distance of 20 yd., another wall was built in front of it, and at the same distance from this second wall a broad moat was constructed with a breastwork along its inner edge. Each wall was flanked by 96 towers. Here was a barricade 190 20 7 ft. thick, and I oo ft. high, with its several parts rising tier above tier to permit concerted action, and alive with large bodies of troops ready to pour, from every coign of vantage, missiles of death—arrows, stones, Greek fire—upon a foe. It is not strange that these fortifications defied the assaults of barbarism upon the civilized life of the world for more than a thousand years. As might be expected, the walls demanded frequent restoration from time to time in the course of their long history. Inscriptions upon them record repairs, for example, under Justin II., Leo the Isaurian, Basil II., John Palaeologus, and others. Still, the ram parts extending now from the Marmora to Tekfour Serai are to all intents and purposes the ruins of the Theodosian walls of the 5th century.

This is not the case in regard to the other parts of the fortifica tions of the city. The walls along the Marmora and the Golden Horn represent the great restoration of the seaward defences of the capital carried out by the emperor Theophilus in the 9th cen tury; while the walls between Tekfour Serai and the Golden Horn were built long after the reign of Theodosius II., super seding the defences of that quarter of the city in his day, and relegating them, as traces of their course to the rear of the later works indicate, to the secondary office of protecting the palace of Blachernae. In 627 Heraclius built the wall along the west of the quarter of Aivan Serai, in order to bring the level tract at the foot of the sixth hill within the city bounds, and shield the church of Blachernae, which had been exposed to great danger during the siege of the city by the Avars in that year. In 813 Leo V. the Armenian built the wall which stands in front of the wall of Heraclius to strengthen that point in view of an expected attack by the Bulgarians.

The splendid wall, flanked by nine towers, that descends from the court of Tekfour Serai to the level tract below Egri Kapu, was built by Manuel Comnenus ( i 143–I 18o) for the greater se curity of the part of the city in which stood the palace of Blach ernae, then the favourite imperial residence. Lastly, the portion of the fortifications between the wall of Manuel and the wall of Heraclius presents too many problems to be discussed here. Enough to say, that in it we find work belonging to the times of the Comneni, Isaac Angelus and the Palaeologi.

If we leave out of account the attacks upon the city in the course of the civil wars between rival parties in the empire, the fortifications of Constantinople were assailed by the Avars in 627; by the Saracens in 673-677, and again in 718; by the Bulgarians in 813 and 913 ; by the forces of the Fourth Crusade in 1203-04 ; by the Turks in 1422 and 1453. The city was taken in 1204, and became the seat of a Latin empire until 1261, when it was recovered by the Greeks. On May 29, 1453 Constantinople ceased to be the capital of the Roman empire in the East, and became the capital of the Ottoman dominion.

The

Walls.—Notable points in the circuit of the walls of the city are the following : (1) The Golden Gate, now included in the Turkish fortress of Yedi Kuleh. It is a triumphal archway, consisting of three arches, erected in honour of the victory of Theodosius I. over Maximus in 388, and subsequently rated in the walls of Theodosius II., as the state entrance of the capital. (2) The gate of Selivria, or of the Pege, through which Alexius Strategopoulos made his way into the city in 1261, and brought the Latin empire of Constantinople to an end. (3) The gate of St. Romanus (Top Kapusi), by which, in 1453, Sultan Mahommed entered Constantinople after the fall of the city into Turkish hands. (4) The great breach made in the ramparts crossing the valley of the Lycus, the scene of the severest fighting in the siege of 1453, where the Turks stormed the city, and the last Byzantine emperor met his heroic death. (5) The palace of the Porphyrogenitus, long eously identified with the palace of the Hebdomon, which really stood at Makrikeui. It is the finest specimen of Byzantine civil architecture left in the city. (6) The tower of Isaac Angelus and the tower of Anemas, with the chambers in the body of the wall to the north of them. (7 ) The wall of Leo, against which the troops of the Fourth Crusade came, in 1203, from their camp on the hill opposite the wall, and delivered their chief attack. (8) The walls protecting the quarter of Phanar, which the army and fleet of the Fourth Crusade under the Venetian doge, Henrico dolo, carried in 1204. (9) Yali Kiosk Kapusi, beside which the southern end of the chain drawn across the mouth of the harbour during i, siege was attached. (so) The ruins of the palace of Hormisdas, near Chatladi Kapu, once the residence of Justinian the Great and Theodora. It was known in later times as the palace of the Bucoleon, and was the scene of the assassination of Nicephorus Phocas. (I I) The sites of the old harbours between Chatladi Kapu and Daud Pasha Kapusi. (I 2) The fine marble tower near the junction of the walls along the Marmora with the landward walls.

Internal.

Arrangements inside the city were determined by the configuration of its site, which falls into three great divi sions—the level ground and slopes looking towards the Sea of Marmora, the range of hills forming the midland portion of the promontory, and the slopes and level ground facing the Golden Horn. In each division a great street ran through the city from east to west, generally lined with arcades on one side, but with arcades on both sides when traversing the finer and busier quar ters. The street along the ridge formed the principal thoroughfare, and was named the Mese (Man), because it ran through the middle of the city. On reaching the west of the third hill, it divided into two branches, one leading across the seventh hill to the Golden gate, the other conducting to the church of the Holy Apostles, and the gate of Charisius (Edirneh Kapusi). The Mese linked together the great fora of the city,—the Augustaion on the south of St. Sophia, the forum of Constantine on the summit of the second hill, the forum of Theodosius I. or of Taurus on the summit of the third hill, the forum of Amastrianon where the mosque of Shah Zadeh is situated, the forum of the Bous at Ak Serai, and the forum of Arcadius or Theodosius II. on the summit of the seventh hill. This was the route followed on the occasion of triumphal processions.

Of the edifices and monuments which adorned the fora, only a slight sketch can be given here. On the north side of the Augus taion rose the church of St. Sophia, the most glorious cathedral of Eastern Christendom; opposite, on the southern side of the square, was the Chalce, the great gate of the imperial palace; on the east was the senate house, with a porch of six noble columns; to the west, across the Mese, were the law courts. In the area of the square stood the Milion, whence distances from Constan tinople were measured, and a lofty column which bore the eques trian statue of Justinian the Great. There also was the statue of the empress Eudoxia, famous in the history of Chrysostom, the pedestal of which is preserved in the Museum gardens. The Augustaion was the heart of the city's ecclesiastical and political life. The forum of Constantine was a great business centre. Its most remarkable monument was the column of Constantine, built of i 2 drums of porphyry and bearing aloft his statue. Shorn of much of its beauty, the column still stands to proclaim the enduring influence of the foundation of the city.

In the forum of Theodosius I. rose a column in his honour, the basis of which was identified in 1927. There also was the Anemodoulion, a beautiful pyramidal structure, surmounted by a vane to indicate the direction of the wind. Close to the forum, if not in it, was the capitol, in which the university of Constanti nople was established. The most conspicuous object in the forum of the Bous was the figure of an ox, in bronze, beside which the bodies of criminals were sometimes burnt. Another hollow column, the pedestal of which is now known as Avret Tash, adorned the forum of Arcadius. A column in honour of the em peror Marcian still stands in the valley of the Lycus, below the mosque of Sultan Mohammed the Conqueror. Many beautiful statues, belonging to good periods of Greek and Roman art, deco rated the fora, streets and public buildings of the city, but confla grations and the vandalism of the Latin and Ottoman conquerors of Constantinople have robbed the world of most of those treasures.

The imperial palace, founded by Constantine and extended by his successors, occupied the territory which lies to the east of St. Sophia and the Hippodrome down to the water's edge. It consisted of a large number of detached buildings, in grounds made beautiful with gardens and trees, and commanding magnifi cent views over the Sea of Marmora, across to the hills and moun tains of the Asiatic coast. The buildings were mainly grouped in three divisions—the Chalce, the Daphne and the "sacred pal ace." Labarte, Paspates and Ebersolt have attempted to recon struct the palace, taking as their guide the descriptions given of it by Byzantine writers. The work of Ebersolt is specially valuable, but without proper excavations of the site all attempts to restore the plan of the palace with much accuracy lack a solid foundation. With the accession of Alexius Comnenus, the palace of Blachernae, at the north-western corner of the city, became the principal residence of the Byzantine court, and was in consequence ex tended and embellished. It stood in a more retired position, and was conveniently situated for excursions into the country and hunting expeditions. Of the palaces outside the walls, the most frequented were the palace at the Hebdomon, now Mak rikeui, in the early days of the empire, and the palace of the Pege, now Balukli, a short distance beyond the gate of Selivria, in later times. For municipal purposes, the city was divided, like Rome, into fourteen regions.

As the seat of the chief prelate of Eastern Christendom, Constantinople was characterized by a strong theological and ecclesiastical temperament. It was full of churches and mona steries, enriched with the reputed relics of saints, prophets and martyrs, which consecrated it a holy city and attracted pilgrims from every quarter to its shrines. It was the meeting-place of numerous ecclesiastical councils, some of them ecumenical (see below, CONSTANTINOPLE, COUNCILS OF). It was likewise dis tinguished for its numerous charitable institutions. Only some 20 of the old churches of the city are left. Most of them have been converted into mosques, but they are valuable monuments of the art which flourished in New Rome. Among the most interest ing are the following: St. John of the Studium (Emir-Achor Jamissi) is a basilica of the middle of the 5th century, and the oldest ecclesiastical fabric in the city; it is now, unfortunately, almost a complete ruin. SS. Sergius and Bacchus (Kutchuk Aya Sofia) and St. Sophia are erections of Justinian the Great. The former is an example of a dome placed on an octagonal structure, and in its general plan is similar to the contemporary church of S. Vitale at Ravenna. St. Sophia (i.e., `A-yia Xo4La, Holy Wis dom) is the glory of Byzantine art, and one of the most beautiful buildings in the world. St. Mary Diaconissa (Kalender Jamissi) is a fine specimen of the work of the closing years of the 6th cen tury. St. Irene, founded by Constantine, and repaired by Jus tinian, is in its present form mainly a restoration by Leo the Isaurian, in the middle of the 8th century. St. Mary Panachrantos (Fenari Isa Mesjidi) belongs to the reign of Leo the Wise (886 .912). The Myrelaion (Bodrum Jami) dates from the loth cen tury. The Pantepoptes (Eski Imaret Jamissi), the Pantocrator (Zeirek Kilisse Jamissi), and the body of the church of the Chora (Kahriyeh Jamissi) represent the age of Comneni. The Pammakaristos (Fetiyeh Jamissi), St. Andrew in Krisei (Khoja Mustapha Jamissi), the narthexes and side chapel of the Chora were, at least in their present form, erected in the times of the Palaeologi. It is difficult to assign precise dates to SS. Peter and Mark (Khoda Mustapha Jamissi at Aivan Serai), St. Theodosia (Gul Jamissi), St. Theodore Tyrone (Kilisse Jamissi). The beautiful facade of the last is later than the other portions of the church, which have been assigned to the gth or loth cen tury.

For a study of the church of St. Sophia, the reader must consult the article BYZANTINE ART. The present edifice was built by Justinian the Great, under the direction of Anthemius of Tralles and his nephew Isidorus of Miletus. It was founded in and dedicated on Christmas Day 538. It replaced two earlier churches of that name, the first of which was built by Constantius and burnt down in 404, on the occasion of the exile of Chrysostom, while the second was erected by Theodosius II. in 415, and destroyed by fire in the Nika riot of 532. Naturally the church has undergone repair from time to time. The original dome fell in 558, as the result of an earthquake, and among the improve ments introduced in the course of restoration, the dome was raised 25 ft. higher than before. Repairs are recorded under Basil I., Basil II., Andronicus III. and Cantacuzene. Since the Turkish conquest a minaret has been erected at each of the four exterior angles of the building, and the interior has been adapted to the requirements of Muslim worship, mainly by the destruc tion or concealment of most of the mosaics which adorned the walls. In 1847-48, during the reign of Abd-ul-Mejid, the building was put into a state of thorough repair by the Italian architect Fossati. Happily the sultan allowed the mosaic figures, then ex posed to view, to be covered with matting before being plastered over. They may reappear in the changes which the future will bring. The dome, which had fallen into considerable disrepair, was reinforced on the outside and reroofed in 1926-27.

The Hippodrome.

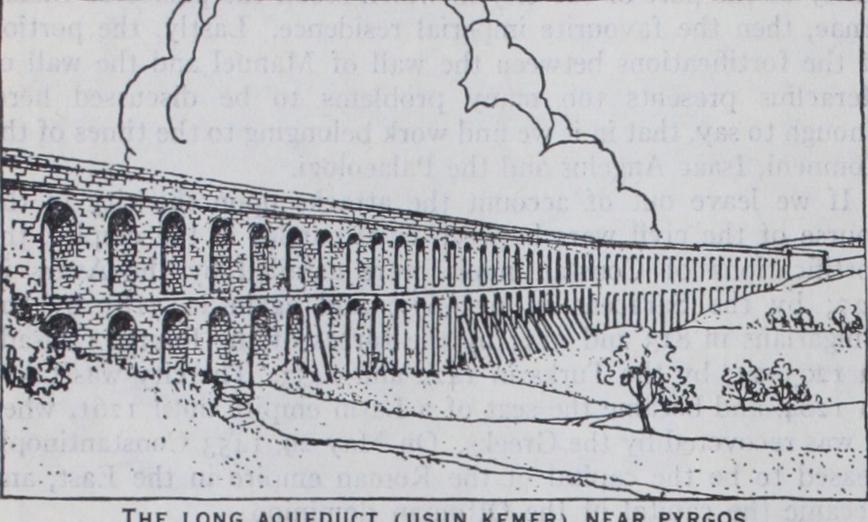

Citizens of Constantinople found recrea tion in the chariot-races held in the Hippodrome, now the At Meidan, to the west of the mosque of Sultan Ahmed. So much did the race-course (begun by Severus) enter into the life of the people that it has been styled "the axis of the Byzantine world." It was not only the scene of amusement, but on account of its ample accommodation it was also the arena of much of the political life of the city. The factions, which usually contended there in sport, often gathered there in party strife. There emperors were ac claimed or insulted; there military triumphs were celebrated; there criminals were executed, and there martyrs were burned at the stake. Three monuments remain to mark the centre of the building; an Egyptian obelisk of Thothmes III., on a pedestal covered with bas-reliefs representing an emperor, presiding at scenes in the Hippodrome; the triple serpent column, which stood originally at Delphi, to commemorate the victory of Plataea 479 B.C. an obelisk, once covered with plates of gilded bronze. Excavations begun by the British Academy in 1927 have recovered the plan and dimensions of the Hippodrome. It is 48o metres long and '17.5 wide.The city was supplied with water mainly from two sources; from the streams immediately to the west, and from the springs and rain impounded in reservoirs in the forest of Belgrade, to the north-west, very much on the system followed by the Turks. The water was conveyed by aqueducts, concealed below the sur face, except when crossing a valley. Within the city the water was stored in covered cisterns, or in large open reservoirs. The aqueduct of Justinian, the Crooked aqueduct, in the open country, and the aqueduct of Valens that spans the valley between the 4th and 3rd hills of the city, still carry on their beneficent work, and afford evidence of the attention given to the water-supply of the capital during the Byzantine period. The cistern of Arcadius, to the rear of the mosque of Sultan Selim (having, it has been estimated, a capacity of 6,571,72o cu.ft. of water), the cistern of Aspar, a short distance to the east of the gate of Adrianople, and the cistern of Mokius, on the seventh hill, are specimens of the open reservoirs within the city walls. The cistern of Bin Bir Derek (cistern of Illus) with its 224 columns, each built up with three shafts, and the cistern Yeri Batan Serai (Cisterna Basilica) with its 42o columns show what covered cisterns were, on a grand scale. The latter is still in use.' Byzantine Constantinople was a great commercial centre. To equip it more fully for that purpose, several artificial harbours were constructed along the southern shore of the city, where no natural haven existed to accommodate ships coming up the Sea of Marmora. For the convenience of the imperial court, there was a small harbour in the bend of the shoie to the east of Chatladi Kapu, known as the harbour of the Bucoleon. To the west of that gate, on the site of Kadriga Limani (the Port of the 'For the ancient water-supply see Count A. F. Andreossy, Constan tinople et le Bosphore; Tchikatchev, Le Bosphore et Constantinople (2nd ed. 1865) ; Forchheimer and Strzygowski, Die byzantinischen Wasserbilailter; also article AQUEDUCT.

Galley), was the harbour of Julian, or, as it was named later, the harbour of Sophia (the empress of Justin II.). Traces of the harbour styled the Kontoscalion are found at Kum Kapu. To the east of Yeni Kapu stood the harbour of Kaisarius or the Heptas calon, while to the west of that gate was the harbour which bore the names of Eleutherius and of Theodosius I. A harbour named after the Golden gate stood on the shore to the south-west of the triumphal gate of the city.

As the capital of the Ottoman empire, the aspect of the city changed in many ways. The works of art which adorned New Rome gradually disappeared. The streets, never very wide, be came narrower, and the porticoes along their sides were almost everywhere removed. A multitude of churches were destroyed, and most of those which survived were converted into mosques. In race and garb and speech the population grew largely oriental. One striking alteration in the appearance of the city was the con version of the territory extending from the head of the promon tory to within a short distance of St. Sophia into a great park, within which the buildings constituting the seraglio of the sultans, like those forming the palace of the Byzantine emperors, were ranged around three courts, distinguished by their respective gates—Bab-i-Humayum, leading into the court of the Janissaries; Orta Kapu, the middle gate, giving access to the court in which the sultan held state receptions; and Bah-i-Saadet, the gate of Felicity, leading to the more private apartments of the palace. From the reign of Abd-ul-Mejid, the seraglio was practically aban doned, first for the palace of Dolmabagche on the shore near Beshiktash, and then for Yildiz Kiosk, on the heights above that suburb. The older apartments of the palace, such as the throne room, the Bagdad Kiosk, and many of the objects in the imperial treasury are of extreme interest to all lovers of oriental art. The seraglio was thrown open to the public in 1926. Another great change in the general aspect of the city has been produced by the erection of stately mosques in the most commanding situa tions. The most remarkable mosques are the following:—The mosque of Sultan Mohammed the Conqueror, built on the site of the church of the Holy Apostles (1463-69), rebuilt in 1768 owing to injuries due to an earthquake; the mosques of Sultan Selim, of the Shah Zadeh, of Sultan Suleiman and of Rustem Pasha—all works of the i6th century, the best period of Turkish architecture; the mosque of Sultan Bayezid II. 0497-1505) ; the mosque of Sultan Ahmed I. (i6ro) ; Yeni-Valide-Jamissi 0 615-1665) ; Nuri-Osmanieh (1748-1755) ; Laleli- Jamissi 0 765) • The Turbehs containing the tombs of the sultans and members of their families are often beautiful specimens of Turkish art.

In their architecture, the mosques present a striking instance of the influence of the Byzantine style, especially as it appears in St. Sophia. The architects of the mosques have made a skilful use of the semi-dome in the support of the main dome of the building, and in the consequent extension of the arched canopy that spreads over the worshipper. In some cases the main dome rests upon four semi-domes. At the same time, when viewed from the exterior, the main dome rises large, bold and commanding, with nothing of the squat appearance that mars the dome of St. Sophia, with nothing of the petty prettiness of the little domes perched on the drums of the later Byzantine churches. The great mosques express the spirit of the days when the Ottoman empire was still mighty and ambitious.

For all intents and purposes, Constantinople is now the col lection of towns and villages situated on both sides of the Golden Horn and along the shores of the Bosporus, including Scutari and Kadikeui. But the chief parts of this group of towns are Istanbul, or Stamboul (from Gr. €1.s racy, "into the city"), the offi cial name of the city since the founding of the republic, Galata and Pera. Galata has a long history, which becomes of general interest after 1265, when it was assigned to the Genoese merchants in the city by Michael Palaeologus, in return for the friendly services of Genoa in the overthrow of the Latin empire of Constantinople. In the course of time, notwithstanding stipula tions to the contrary, the town was strongly fortified and proved a troublesome neighbour. During the siege of 1453 the inhabitants maintained on the whole a neutral attitude, but on the fall of the capital they surrendered to the Turkish conqueror, who granted them liberal terms. The walls have for the most part been re moved. The tower, however, which formed the citadel of the colony, still remains. There are also churches and houses dating from Genoese days. Galata is the chief business centre of the city, the seat of banks, post-offices, steamship offices, etc. Pera is the principal residential quarter of the European communities settled in Constantinople.

Since the middle of the 19th century the city has yielded more and more to western influences, and is fast losing its oriental character. The Galata quay, completed in 1889, is 756 metres long and 20 metres wide; the Stamboul quay, completed in 1900, is 378 metres in length. The harbour, quays and facilities for handling merchandise, which have been established at the head of the Anatolian railway, at Haidar Pasha, would be a credit to any city. The growth of the imperial museum of antiquities, under the direction of Hamdy Bey and Halil Bey has been re markable ; and while the collection of the sarcophagi discovered at Sidon constitutes the chief treasure of the museum, the in stitution has become a rich storehouse of many other valuable relics of the past. The museum of Ottoman art in Tchinili Kiosk and the museum of the ancient Orient are two new additions since 1923. The fine medical school between Scutari and Haidar Pasha, the Hamidieh hospital for children and the asylum for the poor tell of the advance of science and humanity in the place.

Many foreign educational institutions flourish in Constantinople itself, and they are largely attended by the youth belonging to the native communities of the country. The Greek population is pro vided with excellent schools and gymnasia, and the Armenians also maintain schools of a high grade. The old War Office (Seras kerat) in Stamboul is now used to house the University of Stam boul, a new but flourishing institution, based upon the French system.

Transfer of the Capital.

Constantinople passed through several periods of political and economic disaster, relieved only by very brief periods of normal life and prosperity, during the years 190o to 1925. Four wars following each other in quick suc cession caused at times a complete cessation of trade, the influx of hordes of refugees, demoralization in the organization and regulation of civic life, loss of population and an acute impoverish ment of all classes. Within this period also Constantinople lost, in theory as well as in fact, the position held well-nigh uninter ruptedly for 16 centuries—that of the headship of a great empire. During the Balkan wars (1912-13) the city narrowly escaped capture by the Bulgarians; the refugees who poured in from Thrace taxed the resources of the city to the utmost, and the loss of European provinces unfavourably affected its trade posi tion. During the World War the city was in a state of complete blockade by sea, subjected to numerous air attacks, and during the last months before the Armistice, almost denuded of food, fuel and other necessities of life. The outstanding features of the period of the occupation by Great Britain, France and Italy (Nov. 13, 1918–Oct. 2, 1923) were: a short period in 1919-20 of intense commercial activity and relative prosperity, brought to an abrupt end in 1921 by the combined effects of the war in Anatolia and the worldwide trade depression; the outbreak in 1919 of the nationalist movement and the Greek war ; the invasion of the city in 1919 and 1920 by some 100,000 destitute refugees, the bulk of whom were Turks (30,00o) and Russians (65,00o) ; the arrival in the city at intervals, mostly in 1922 and 1923, of over 200,000 Greek deportees from Anatolia, most of whom were speedily moved on to Greece ; the seizure of the machinery of government by the nationalists after the Mudaniya armistice in Oct. 1922; the flight of the deposed sultan, Mehmed VI., on Nov. 17, 1922; and the formal evacuation of the city by the Allies on Oct. 2, 1923.The vital factor in the fortunes of the city was its relation to the nationalist movement. When, in March 192o, the British attempted to suppress the activities of those supporters of the nationalist movement who were still in the city, many were exiled to Malta, and thousands of sympathizers left for Anatolia to assist in the task of liberation. The Anatolian leaders determined that Constantinople should no longer exact that tragic tribute of lives and treasure which had repeatedly exhausted their country in the past and the subordination of Constantinople to Angora and Anatolia was definite and complete when, on March 3, the caliph, Abdul Mejid, was expelled and the city thus deprived of even the shadow of its former sovereignty.

After a period of opposition, the population has accepted the new situation and Constantinople remains important as Turkey's link with the outside world in commerce.

Climate.

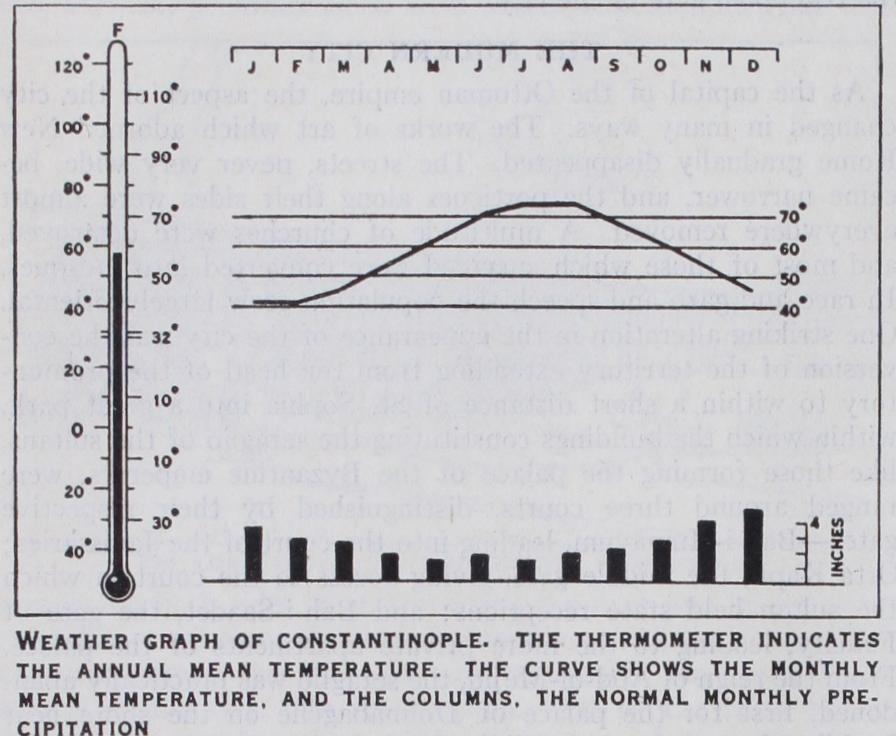

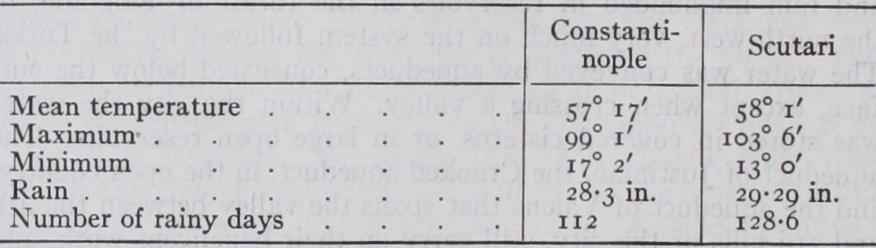

The climate of the city is healthy, but relaxing. It is damp and liable to sudden and great changes of temperature. The winds from the north and those from the south are at con stant feud, and blow cold or hot in the most capricious manner, often in the course of the same day. "There are two climates at Constantinople, that of the north and that of the south wind." The winters may be severe, but when mild they are wet and not invigorating. In summer the heat is tempered by the prevalence of a north-east wind that blows down the channel of the Bosporus. Observations at Constantinople and at Scutari give the following results, for a period of twenty years.

The sanitation of the city has been improved, although much remains to be done in that respect. No great epidemic has visited the city since the outbreak of cholera in 1866. Typhoid and pul monary diseases are common.

Population.

The population was given in 1924 as 1,o65,866. A careful census in 1927 credited the Vilayet with 794,444, of whom 547,126 were Muslims, 10o,214 Greeks, 53,129 Armenians, Jews, 23,930 Catholics, 16,696 Chietiens, and 4,421 Protestants. The diversity of language is also extreme.

Water-supply.

The sultans enlarged and increased the res ervoirs in the forest of Belgrade, and new aqueducts were added to those erected by the Byzantine emperors. Old cisterns within the walls were abandoned, and water led to basins in vaulted chambers (Taxim), from which it is distributed by underground conduits to fountains.For the supply of Pera, Galata and Beshiktash, Sultan Mahmud I. constructed, in 1732, four bends in the forest of Belgrade, N.N.W. and N.E. of the village of Bagchekeui, and the fine aque duct which spans the head of the valley of Buyukdere. Since 1885, a French company, La Compagnie des Eaux, has rendered a great service by bringing water to Stamboul, Pera, and the villages on the European side of the Bosporus, from Lake Dercos, which lies close to the shore of the Black Sea some 29 m. distant from the city. The Dercos water is laid on in many houses. Since a German company has supplied Scutari and Kadikeui with water from the valley of the Sweet Waters of Asia.

Administration.—For the preservation of order and security, the city is divided into four divisions (Belad-i-Selassi), viz., Stamboul, Pera-Galata, Beshiktash and Scutari.

The municipal government of the four divisions of the city is in the hands of a prefect, appointed by the president of the re public, and subordinate to the minister of the interior. He is officially styled the prefect of Stamboul, and is assisted by a council of twenty-four members, appointed by the president or the minister of the interior. The city is furthermore divided into ten municipal circles as follows. In Stamboul: (I) Sultan Baye zid, (2) Sultan Mehemet, (3) Djerah Pasha (Psamatia) ; on the European side of the Bosporus and the northern side of the Golden Horn: (4) Beshiktash, (5) Yenikeui, (6) Pera, (7) Buy ukdere ; on the Asiatic side of the Bosporus: (8) Anadol Hissar, (9) Scutari, (io) Kadikeui. Each circle is subdivided into several wards (mahalleh). The outlying parts of the city are divided into six districts (Cazas), namely, Princes' islands, Guebzeh, Beicos, Kartal, Kuchuk-Chekmedje and Shile, each having its governor (kaimakam). These districts are dependencies of the ministry of the interior, and their municipal affairs are directed by agents of the prefecture.

Modernization of Constantinople.—The modernization of the city made remarkable strides in spite of the adverse condi tions. In 1912 electric lighting and in 1913 and 1914 the first electric tramways and telephones were introduced. During the war period the municipal organization and services seriously de teriorated. With the restoration of complete Turkish control, and particularly under the energetic administration of the prefect, Dr. Emin Bey, a decided change for the better took place. A genuinely effective fire-fighting organization was created for the first time in the history of the city, periodically devastated throughout its long history by terrible fires; the condition of the streets, which during the occupation were morally and materially in a deplorably unclean state, was improved; 25 km. of new roads were con structed and 2 5o krz. of old roads repaired ; the water supply was augmented; the construction of a thoroughly modern sewage system was begun in Stamboul; a new slaughter house, an ice factory and refrigerating plant, six dispensaries and a hospital were built and placed under municipal management. During 1925 the city budget was increased from ŁT4,000,000 to ŁT6,5oo,000. The former imperial palace Yildiz was leased to an Italian entre preneur for conversion into a casino, and it was hoped that this would be a source of revenue to the city.

The city remains the educational and cultural centre of the nation. The National University was installed in the commodious buildings of the old War Office. The two normal schools, one for men and one for women, continue to function. Since 1923, 4o new secondary and primary schools have been established, mak ing a total in 1926 of 562 schools with 81,865 students. The foreign schools which existed before 1914 are allowed to continue their work, but no new ones may be opened.

The most striking social changes relate to the status of women. The veil was almost completely discarded during the World War, and in 1925 the European hat began to supplant the traditional "charshaf." Men and women mingle freely in the streets and at public gatherings, and the compartments reserved for women in public conveyances have been done away with. The university has opened all its departments to women. The complete sup pression in 1925 of the fez and the adoption of European headgear for men removed one more picturesque and distinctive feature of the life of the city.

The capitulations (q.v.) were abolished in 1914 and their abolition confirmed by the Treaty of Lausanne. The old Ottoman code has been replaced by one based upon the Swiss Code. It became effective in Oct. 1926. Foreigners have a right to establish their own schools and hospitals, and to hold their special religious services.

The commercial life of Constantinople was revolutionized by the wars of 1912-23. In 1919 and 192o the port revived in con nection with transit trade to Russia and Rumania, but in 1921 this revival collapsed. Instability of Turkish currency, the un certainty for a while on the part of Greek merchants as to whether they would be allowed to remain or would be "exchanged" as were being their compatriots in other parts of Turkey, new taxation and poverty of post organization all helped to weaken Constanti nople, but worldwide trade depression and war in Anatolia were prime causes. However, 1924 showed some improvement on 1923 and 1926 some improvement on 1925. Coastwise trade has been reserved for Turkish vessels (1926), and a port monopoly for handling goods established (1925). The tonnage of vessels In transit through the port of Constantinople in 1926 was only 11.6% less than the corresponding tonnage for 1908, but the number of vessels carrying out commercial operations in the port has declined by over so% since that year. (A. VAN M. ; X. ) BIBLIOGRAPHY.-On Constantinople generally, besides the regular guide-books and works already mentioned, see P. Gyllius, De topo graphia Constantinopoleos, De Bosporo Thracio (1623) ; Du Cange, Constantinopolis Christiana (168o) ; J. von Hammer, Constantinopolis and der Bosporos (1822) ; Mordtmann, Esquisse topograpkique de Constantinople (1892) ; E. A. Grosvenor, Constantinople (1895) ; van Millingen, Byzantine Constantinople (1899) ; Paspates, Bu3'avri va MeXEraL (1877) ; Scarlatos Byzantios 'H Kwvoravrlvou zrbXts (1851) ; E. Pears, Fall of Constantinople (1885), The Destruction of the Greek Empire (1903) ; Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire; Salzenberg, Altchristliche Baudenkmaler von Konstantinopel; Lethaby and Swainson, The Church of Sancta Sophia; Pulgher, Les Anciennes Eglises byzantines de Constantinople; Labarte, Le Palais imperial de Constantinople et ses abords. Djelal Essad, Constantinople, de Byzance a Stamboul (1909) ; J. Ebersolt: Le grand palais (191o) ; A. Van Mil lingen, Byzantine Churches in Constantinople (1912) ; J. Ebersolt and A. Thiers, Les Eglises de Constantinople (1913) ; G. Schlumberger, Le Siege, la Prise et le Sac de Constantinople par les Turcs en H. G. Dwight, Constantinople, Old and New (1915) ; E. Pears, Forty Years in Constantinople (1916) ; C. Diehl, Dans l'orient byzantin (1917) ; J. Ebersolt, Constantinople byzantine et les voyageurs du Levant (1919) ; C. R. Johnson, Constantinople To-Day (A social sur vey of the modern city) (1922) ; C. Diehl, Constantinople (1924) ; George Young, Constantinople (1926) ; E. Mambourg; Tourists' Guide (1927). Reports of the Department of Overseas Trade, London.