Contrapuntal Forms

CONTRAPUNTAL FORMS, in music. The forms of music may be con sidered in two aspects, the texture of the music from moment to moment and the shape of the musical design as a whole. Historically the texture of music became definitely organized long before the shape could be determined by any but external or mechanical con ceptions. The laws of musical texture were known as the laws of "Counterpoint" (see COUNTERPOINT and HARMONY). The "con trapuntal" forms, then, are historically the earliest and aestheti cally the simplest in music ; the simplest, that is to say, in prin ciple, but not necessarily the easiest to appreciate or to execute. Their simplicity is like that of mathematics, the simplicity of the elements involved ; it develops into results more subtle and intri cate than popular; whereas much of the art that is popular con tains many and various elements combined in ways which, though familiar in appearance, are often not recognized for the complex conventions of civilization that they really are.

I. CANONIC FORMS AND DEVICES In the canonic forms, the earliest known in music as an inde pendent art, the laws of texture also determine the shape of the whole, so that it is impossible, except in the light of historical knowledge, to say which is prior to the other. The principle of canon being that one voice shall reproduce note for note the ma terial of another, it follows that in a composition where all parts are canonic and where the material of the leading part consists of a pre-determined melody, such as a Gregorian chant or a popular song, the composer has nothing to do but to adjust minute detail till the harmonies fit. The whole composition is the predetermined melody plus the harmonic fitness. The art does not teach com position, but it does teach fluency under difficulties, and thus the canonic forms play an important part in the music of the 15th and 16th centuries; nor indeed have they since fallen into neglect without grave injury to the art. But strict canon is inadequate, and may become a nuisance, as the sole regulating principle in music ; nor is its rival and cognate principle of counterpoint on a Canto Fermo (see p. 349) more trustworthy in primitive stages. These are rigid mechanical principles ; but even mechanical prin ciples may force artistic thought to leave the facile grooves of custom and explore the real nature of things. Even to-day the canonic forms are great liberators if studied with intelligence.

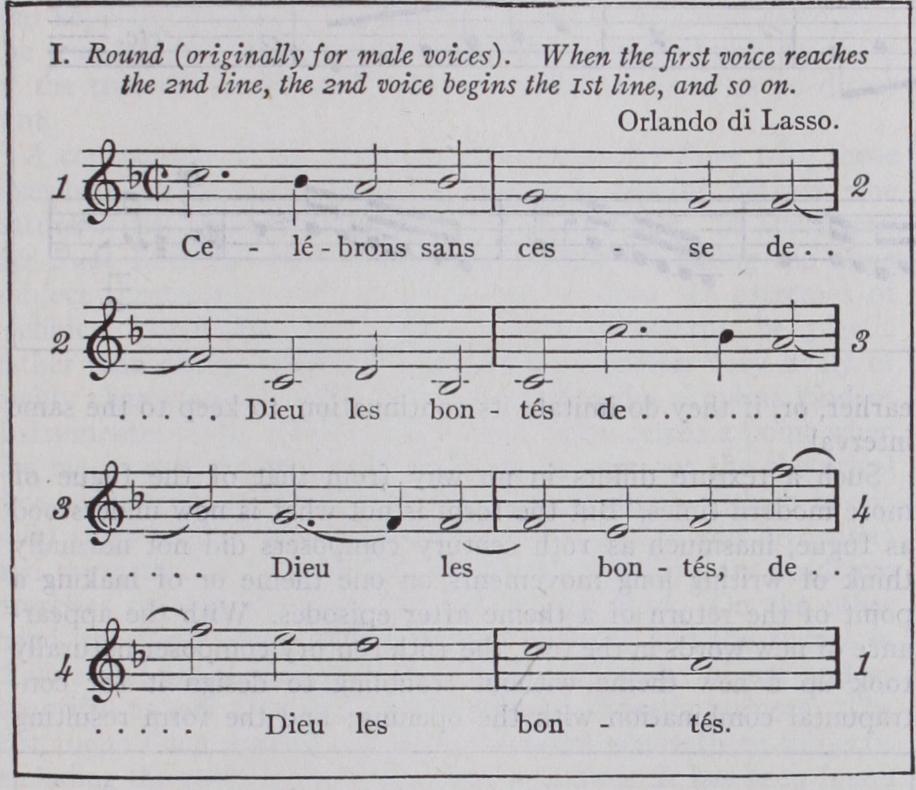

The earliest canonic form is the rondel or rota as practised in the 12th century. It is, however, canonic by accident rather than in its original intention. It consists of a combination of short melodies in several voices, each melody being sung by each voice in turn. Now it is obvious that if one voice began alone, instead of all together, and if when it went on to the second melody the second voice entered with the first, and so on, the result would be a canon in the unison. Thus the difference between the crude counterpoint of the rondel and a strict canon in the unison is a mere question of the point at which the composition begins, and a I 2th century rondel is simply a canon at the unison begun at the point where all the voices have already entered. There is some reason to believe that one kind of rondeau practised by Adam de la Hale was intended to be sung in the true canonic manner of the modern round ; and the wonderful English rota, "Sumer is icumen in," shows in the upper four parts the true canonic method, and in its two-part pes the method in which the parts began to gether (see Music, Ex. 1). In these archaic works the canonic form gives the whole a stability contrasting oddly with its cacoph onous warfare between nascent harmonic principles and ancient antiharmonic criteria. As soon as harmony became established on the true contrapuntal basis, the unaccompanied round attained the position of an elegant trifle, with hardly more expressive possi bilities than the triolet in poetry, a form to which its brevity and lightness renders it fairly comparable. Orlando di Lasso's Celebrons sans cesse is a beautiful example of the i 6th century round with a delightful climax in its fourth line : (see I., below).

In classical times the possibilit'es of the round enormously in creased; and with the aid of elaborate instrumental accompani ments it plays an important feature at points where a tableau is possible in an operatic ensemble. In such a round the first voice can execute a long and complete melody before the second voice joins in. Even if this melody be not instrumentally accompanied, it will imply a certain harmony, or at all events arouse curiosity as to what the harmony is to be. And the sequel may shed a new light upon the harmony, and thus by degrees the whole character of the melody may be transformed. The humorous and subtle possibilities of this form were first fully revealed by Mozart, whose astounding unaccompanied canons would be better known but for his habit of extemporizing unprintable texts for them.

The round or the catch (which is simply a specially jocose round) is a favourite English art-form, and the English specimens of it are almost as numerous and sometimes as anonymous as folk songs. But they are apt to achieve only the easy task comprised in a good piece of free and fairly contrapuntal harmony in three or more parts, so arranged that it remains correct when the parts are brought in one by one. Even Cherubini gives hardly more than a valuable hint that the round may rise to higher things; and, unless he be an adequate exception, the unaccompanied rounds of Mozart and Brahms stand alone as works that raise the round to the dignity of a serious art-form.

With the addition of an orchestral accompaniment the round obviously becomes a larger thing; and in such specimens as that in the finale of Mozart's Cosi fan tutte, the quartet in the last act of Cherubini's Faniska, the wonderfully subtle quartet "Mir ist so wunderbar" in Beethoven's Fidelio, and the very beautiful num bers in Schubert's masses where Schubert finds expression for his genuine contrapuntal feeling in lyric style, we find that the length of the initial melody, the growing variety of the orchestral accompaniment and the finality and climax of the free coda, com bine to give the whole a character closely analogous to that of a set of contrapuntal variations, such as the slow movement of Haydn's "Emperor" string quartet, or the opening of the finale of Beethoven's gth symphony. Berlioz is fond of beginning his largest movements like a kind of round; e.g. his Dies Irae, the Scene aux Champs in the Symphonie Fantastique, and the opening of his Damnation de Faust.

Three conditions are necessary if a canon is to be a round. First, the voices must imitate each other in the unison; secondly, they must enter at equal intervals of time ; and thirdly, the whole melodic material must be as many times longer than the interval of time as the number of voices; otherwise, when the last voice has finished the first phrase, the first voice will not be ready to return to the beginning. Strict canon is, however, possible under innu merable other conditions, and even a round is possible with some of the voices at the interval of an octave, as is of course inevitable in writing for unequal voices. And in a round for unequal voices there is obviously a new means of effect in the fact that, as the melody rotates, its different parts change their pitch in relation to each other.

The art by which this is possible without incorrectness is that of double, triple and multiple counterpoint (see COUNTERPOINT). Its difficulty is variable, and with an instrumental accompaniment there is none. In fugues, multiple counterpoint is one of the nor mal resources of music ; and few devices are more self-explanatory to the ear than the process by which the subject and counter subjects of a fugue change their positions, revealing fresh melodic and acoustic aspects of identical harmonic structure at every turn. This, however, is rendered possible and interesting by the fact that the passages in such counterpoint are often separated by episodes and are free to appear in different keys. Many fugues of Bach are written throughout in multiple counterpoint; but the possibility of this depends upon the freedom of the musical design which allows the composer to select the most effective permuta tions and combinations of his counterpoint, and also to put them into whatever key he chooses. Some of Bach's choruses might be called Round-Fugues, so regular is the course by which each voice proceeds to a new counter-subject as the next voice enters. See the Et in terra pax of the B minor Mass, and the great double chorus, Nun ist das Heil.

The resources of canon, when emancipated from the principles of the round, are considerable when the canonic form is strictly maintained, and are inexhaustible when it is treated freely. A canon need not be in the unison; and when it is in some other interval the imitating voice alters the expression of the melody by transferring it to another part of the scale. Again, the imitating voice may follow the leader at any distance of time; and thus we have obviously a definite means of expression in the difference of closeness with which various canonic parts may enter ; as, for instance, in the stretto of a fugue. Again, if the answering part enters on an unaccented beat where the leader began on the accent (per arsin et thesin), there will be artistic value in the resulting difference of rhythmic expression. All these devices ought to be quite definite in their effect upon the ear, and their expressive power is undoubtedly due to their special canonic nature. The beauty of the pleading, rising sequences in crossing parts in the canon at the and at the opening of the Recordare in Mozart's Requiem is attainable by no other technical means. The close canon in the 6th at the distance of one minim in reversed accent in the i8th of Bach's Goldberg Variations owes its smooth harmonic expression to the fact that the two canonic parts move in sixths which would be simultaneous but for the pause of the minim which reverses the accents of the upper part while it creates the suspended discords which give harmonic character.

Two other canonic devices have important artistic value, viz., augmentation and diminution (two different aspects of the same thing) and inversion. In augmentation the imitating part sings twice as slow as the leader, or sometimes still slower. This ob viously should impart a new dignity to the melody, and in dimi nution the usual result is an accession of liveliness. Beethoven, in the fugues in his sonatas opp. io6 and i io, adapted augmenta tion and diminution to sonata-like varieties of thematic expres sion, by employing them in triple time, so that, by doubling the length of the original notes across this triple rhythm, they produce an entirely new rhythmic expression. (See C.) The device of inversion consists in the imitating part reversing every interval of the leader, ascending where the leader descends and vice versa. Its expressive power depends upon so fine a sense of the harmonic expression of melody that its artistic use is one of the surest signs of the difference between classical and merely scholastic music. There are many melodies of which the inversion is as natural as the original form, and does not strikingly alter its character. Such are, for instance, the theme of Bach's Kunst der Fuge, most of Purcell's contrapuntal themes, the theme in the fugue of Beethoven's sonata, op. o, and the eighth of Brahms's variations on a theme by Haydn. But even in such cases inver sion may produce harmonic variety as well as a sense of melodic identity in difference. Where a melody has marked features of rise and fall, such as long scale passages or bold skips, the inversion, if productive of good harmonic structure and expres sion, will be a powerful method of transformation. This is admirably shown in the 2th of Bach's Goldberg Variations, in the 5th fugue of the first book of his Forty-eight Preludes and Fugues, in the finale of Beethoven's sonata, op. io6, and in the second subjects of the first and last movements of Brahms's clarinet trio. The only remaining canonic device which figures in classical music is that known as cancrizans, in which the imitating part reproduces the leader backwards. It is of extreme rarity in serious music; and, though it sometimes happens that a melody or figure of uniform rhythm will produce something equally natural when read backwards (as in III.), there is only one example of its use that appeals to the ear as well as the eye. This is to be found in the finale of Beethoven's sonata, op. Too, where it is applied to a theme with such sharply contrasted rhythmic and melodic features that with long familiarity a listener would prob ably feel not only the wayward humour of the passage in itself, but also its connection with the main theme. All these devices are also independent of the canonic idea, since there are so many methods of transforming themes in themselves, and need not always be used in contrapuntal combination.