Cookery

COOKERY. The art of preparing and dressing food of all sorts for human consumption, of converting the raw materials, by the application of heat or otherwise, into a digestible and pleasing condition, and generally ministering to the satisfaction of the ap petite and the delight of the palate.

Ancient Cookery.—It is obvious that opportunity has domi nated its history, for the art of cookery is to some extent the prod uct of an increased refinement of taste, consequent on culture and increase of wealth. To this extent it is a decadent art, minis tering to the luxury of man, and to his progressive inclination to be pampered and have his appetite tickled. The Greeks learnt by contact with Asia to increase the sumptuous character of their banquets, but we know little enough of their ideas of gastronomy. Athens was the centre of luxury. According to our chief authority, Athenaeus, Archestratus of Gela, the friend of the son of Pericles, the guide of Epicurus, and author of the Heduphagetica, was a great traveller, and took pains to get information as to how the delicacies of the table were prepared in different parts. His lost work was versified by Ennius. Other connoisseurs seem to have been Numenius of Heraclea, Hegemon of Thasos, Philogenes of Leucas, Simonaclides of Chios and Tyndarides of Sicyon. The Romans, emerging from their pristine simplicity, borrowed from the Greeks their achievements in gastronomic pleasure. We read of this or that Roman gourmet, such as Lucullus, his extravagances and his luxury. The name of the connoisseur Apicius, after whom a work of the time of Heliogabalus is called, comes down to us in association with a manual of cookery. And from Macrobius and Petronius we can gather very interesting glimpses of the Roman idea of a menu. In the later empire, tradition still centred round the Roman cookery favoured by the geographical position of Italy; while the customs and natural products of the remoter parts of Europe gradually begin to assert themselves as the middle ages progress.

The Renaissance.

It is, however, not till the Renaissance, and then too with Italy as the starting-point, that the history of mod ern cookery really begins.Montaigne's references to the revival of cookery in France by Catherine de' Medici indicates that the new attention paid to the art was really novel. She brought Italian cooks to Paris and intro duced there a cultured simplicity which was unknown in France before. It is to the Italians apparently that later developments are originally due. It is clearly established, for instance (says Abra ham Hayward in his Art of Dining), that the Italians introduced ices into France. Fricandeaus were invented by the chef of Leo X. And Coryate in his Crudities, writing in the time of James I., says that he was called "f urcif er" (evidently in contemptuous jest) by his friends, from his using those "Italian neatnesses called forks." The use of the fork and spoon marked an epoch in the progress of dining, and consequently of cookery.

Under Louis XIV. further advances were made. His maitre d'hôtel, Béchamel, is famous for his sauce; and Vatel, the great Conde's cook, was a celebrated artist, of whose suicide in despair at the tardy arrival of the fish which he had ordered Madame de Sevigne relates a moving story. The prince de Soubise, immor talized by his onion sauce, also had a famous chef.

In England, the names of certain cookery-books may be noted, such as Sir J. Elliott's (1539), Abraham Veale's (1575), and the Widdowe's Treasure (1625). The Accomplisht Cook, by Robert May, appeared in 1665, and from its preface we learn that the author (who speaks disparagingly of French cookery, but more gratefully of Italian and Spanish) was the son of a cook, and had studied abroad and under his father (c. 161o) at Lady Dormer's, and he speaks of that time as "the days wherein were produced the triumphs and trophies of cookery." From his description they consisted of most fantastic and elaborately built-up dishes intended to amuse and startle, no less than to satisfy the appetite and palate.

French Cookery.

Louis XV. was a great gourmet; and his reign saw many developments in the culinary art. The mayonnaise (originally mahonnaise) is ascribed to the duc de Richelieu. Such dishes as "potage a la Xavier," "cailles a la Mirepoix," "chartreuses a la Mauconseil," "poulets a la Villeroy," "potage a la Conde," "gigot a la Mailly," owe their titles to celebrities of the day, and the Pompadour gave her name to various others. The Jesuits, Brunoy and Bougeant, who wrote a preface to a contemporary treatise on cookery (1739), described the modern art as "more simple, more appropriate, and more cunning, than that of old days," giving the ingredients the same union as painters give to colours, and harmonizing all the tastes. The very phrase "cordon bleu" (strictly applied only to a woman cook) arose from an en thusiastic recognition of female merit by the king himself.The French Revolution was temporarily a blow to Parisian cook ery, as to everything else of the ancien regime. "Not a single tur bot in the market," was the lament of Grimod de la Reyniere, the great gourmet, and author of the Manuel des amphitryons (1808). But while it fell heavily on the class of noble amphitryons it had one remarkable effect on the art which was epoch-making. It is from that time that we notice the rise of the Parisian restaurants. To 1770 is ascribed the first of these, the Champ d'oiseau in the rue des Poulies. In 1789 there were loo. In 1804 (when the Alma stack des gourmands, the first sustained effort at investing gastron omy with the dignity of an art, was started) there were between 500 and 600. And in 1814, to such an extent had the restaurants attracted the culinary talent of Paris, that the allied monarchs, on arriving there, had to contract with the two brothers Very for the supply of their table. Among the great gastronomic names of Napoleon's day was that of his chancellor Cambaceres, of whose dinners many stories are told. Robert (the eponym of the sauce Robert), Rechaud, and Merillion were at this period esteemed the Raphael, Michelangelo and Rubens of cookery; while A. Beau villiers (author of Art des cuisines) and Careme (author of the Maitre d'hôtel francais, and chef at different times to the tsar Alexander I., Talleyrand, George IV. and Baron Rothschild) were no less celebrated. Perhaps the greatest name of all in the history of the literature of cookery is that of Anthelme Brillat-Savarin the French judge and author of the Physiologie du Gout (1825), the classic of gastronomy.

Later History.

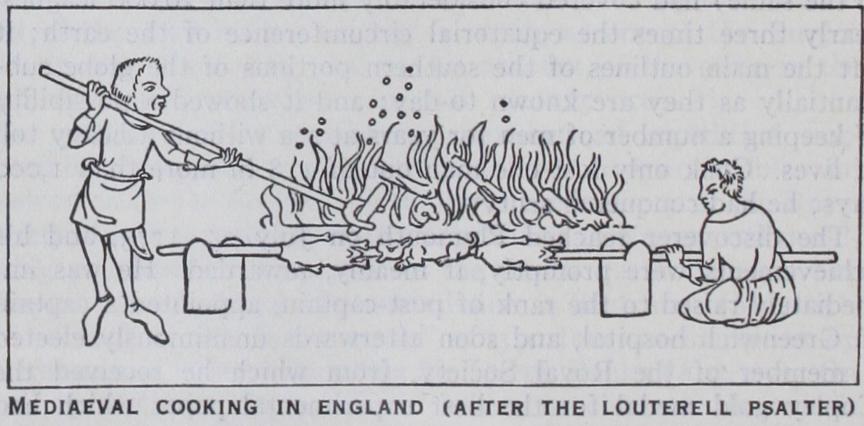

In England, Louis Eustache Ude, Charles Elme Francatelli and Alexis Soyer carried on the tradition, all be ing not only cooks but authors of treatises on the art. The Original (1835) of Thomas Walker, the Lambeth police magistrate, is another work which has inspired later pens. Like the Physiologie du Goat, it is no mere cookery-book, but a compound of observa tion and philosophy. Among simple hand-books, Mrs. Glasse's, Dr. Kitchener's, and Mrs. Rundell's were standard English works in the 18th and early 19th centuries ; and in France the Cuisiniere de la Campagne (1818) went through edition after edition. An interesting old English work is Dr. Pegge's Forme of Cury (178o) , which includes some historical reflections on the subject. "We have some good families in England," he says, "of the name of Cook or Coke. . . . Depend upon it, they all originally sprang from real professional cooks, and they need not be ashamed of their extraction any more than Porters, Butlers, etc." He points out that cooks in early days were of some importance ; William the Conqueror bestowed land on his coquorum praepositus and coquus regius; and Domesday Book records the bestowal of a manor on Robert Argyllon, by the service of a dish called "de la Groute" on the king's coronation day.At the present time, whatever the local varieties of cooking, and the difference of national custom, French cooking is admittedly the ideal of the culinary art, directly we leave the plain roast and boiled. And the spread of cosmopolitan hotels and restaurants over England, America and the European continent, has largely accustomed the whole civilized world to the Parisian type. The improvements in the appliances and appurtenances of the kitchen have made the whole world kin in the arts of dining, but the French chef remains the typical master of his craft. See GAS