Corsica

CORSICA, a large island of the Mediterranean, forming a department of France. It is situated immediately to the north of Sardinia (from which it is separated by the narrow strait of Bonifacio), between 41° 21' and 43° N. and 8° 3o' and 9° 3o' E. Area 3,367 sq.m. Pop. Corsica lies within 54 m. W. of the coast of Tuscany, 98 m. S. of Genoa and 106 m. S.E. of the French coast at Nice. The extreme length of the island is I 14 m. and its average breadth c. 6o m.

A central granitic ridge describes a curve from north-west to south-west and from it spurs diverge in all directions, separating narrow river valleys and forming bold headlands along the west ern coast. A large mass of granophyres, quartz porphyries and similar rocks form the high mountains around Mont Cinto (8,881 ft.). Other important heights are Monts Rotondo (8,612 ft.), Paglia Orba (8,284 ft.), Padro (7,851 ft.) and d'Oro (7,845 ft.). Between the gulfs of Porto and Galeria occur schists, limestones and anthracite containing fossils of Upper Carboniferous age. To the east and north-east of a line drawn from Belgodere through Corte to Favone, schists of unknown age, with intrusive masses of serpentine and euphotide, are the principal rocks. This north-east part of the island is thought by Staub to be a portion of the Alpine fold system, while the rest of the island would be part of the foreland against which the folding occurred. Folded amongst the schists are strips of Upper Carboniferous beds simi lar to those of the west coast. Overlying these rocks are lime stones with Rhaetic and Liassic fossils, occurring at Oletto, Moro saglia, etc. Nummulitic limestone of Eocene age is found near St. Florent, and occupies several large basins near the boundary between the granite and the schist. Miocene molasse with • Clypeaster, etc., forms the plain of Aleria and occurs also at St. Florent in the north and Bonifacio in the south. The caves of Corsica, especially in the neighbourhood of Bastia, contain numer ous mammalian remains. The regularity of the east coast con trasts strikingly with the mountain-girdled inlets of the west, and considerable areas are covered by lagoons. The rivers and tor rents, though short in their courses, bring down large volumes of water from the mountains. The longest is the Golo, which rises in the isolated region of Niolo to the west of Corte and en ters the sea to the south of the Etang de Biguglia; farther south is the Tavignano, while on the west there are the Liamone, the Gravone and the Taravo.

The climate of the island ranges from warmth in the lowlands to extreme rigour in the mountains. The intermediate region is the most temperate and healthy. The mean annual temperature at Ajaccio is 63 ° F. The dominant winds are from the south-west and south-east.

Agriculture suffers from scarcity of labour, apathy and scarcity of capital. Cereals, despite fertility of the soil, are neglected.

The culture of the vine, cedrates, citrons and olives (for which the Balagne region, in the north-west, is noted), of vegetables and of tobacco, and sheep and goat rearing are the main rural indus tries, to which may be added the rearing of silk-worms. The ex ploitation of the forests tends to proceed too rapidly. Chestnuts are exported, and, ground into flour, are used as food by the mountaineers. Most of the inhabitants are proprietors of land, but often the properties are split up to include vineyard or olive plantation, arable land in the plain, and a chestnut-wood in the mountain. Agricultural labourers from Tuscany and Lucca pe riodically visit the island. The mouflon, perhaps an ancestral type of sheep, inhabits the more inaccessible parts of the moun tains. A thick tangled underwood, known as the maquis, generally covers the uncultivated districts. Game and freshwater fish are abundant. The fisheries of tunny, pilchard and anchovy supply some of the Italian markets, but comparatively few of the natives are engaged in this industry. The practice of the blood-feud or vendetta has not yet died out. Each individual belongs to some powerful family, with the political views of which he has to con form; the competition for official posts has seriously affected commerce and agriculture.

The manufactures include the extraction of gallic acid from chestnut-bark, the preparation of preserved citrons and other delicacies, and of macaroni and similar foods and the manufac ture of fancy goods and cigars. There are mines of anthracite, antimony and copper ; the island produces granite, building stone, marble and amianthus, and there are salt marshes. Among other places Guagno, Pardina Guitera and Orezza have mineral springs.

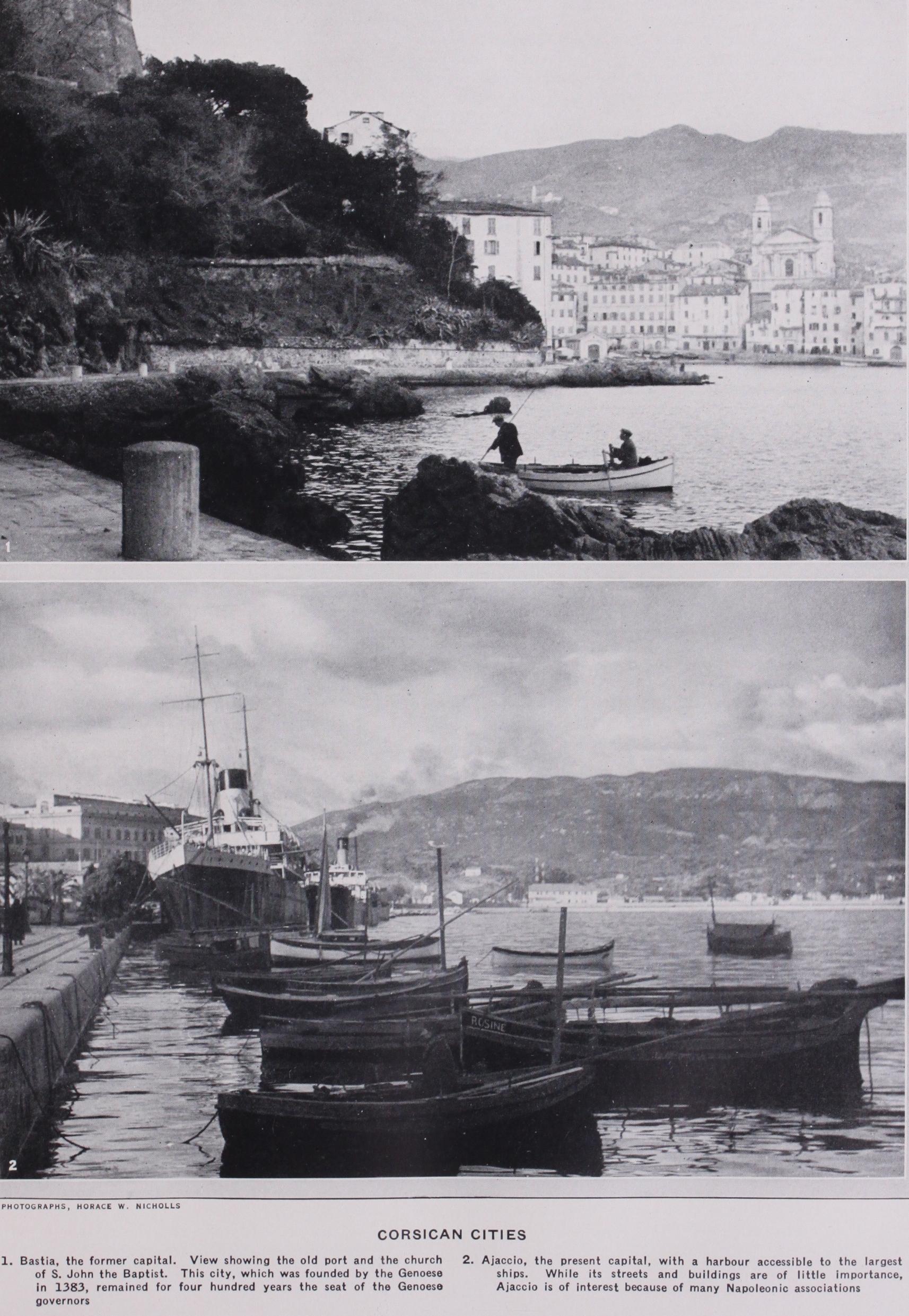

The chief ports are Bastia, Ajaccio and Ile Rousse. A railway runs from Bastia to Ajaccio with branches to Ile Rousse and Calvi on the west coast and Ghisonaccia on the eastern seaboard. but, in general, lack of means of communication as well as of capital is a barrier to commercial activity. Corsica exports early produce, fruits, fresh and preserved, olive oil, wood, charcoal, tanning bark, gallic acid, mineral waters, game, fish, skins, cheese.

Corsica is divided into four arrondissements (chief towns Ajaccio, Bastia, Corte and Sartene), with 62 cantons and 364 communes. It forms part of the academie (educational circum scription) and archiepiscopal province of Aix (Bouches-du Rhone) and of the region of the XV. Army Corps. The principal towns are Ajaccio, the capital and the seat of the bishop of the island and of the prefect ; Bastia, the seat of the court of appeal and of the military commander; Calvi, Corte and Bonifacio. Other places of interest are St. Florent, near which stand the ruins of the cathedral (12th century) of the vanished town of Nebbio; Murato, which has a church (12th or 13th century) of Pisan architecture, also exemplified in other Corsican churches; and Cargese, where there is a Greek colony, dating from the I 7th century. Near Lucciana are the ruins of a Romanesque church called La Canonica. Megalithic monuments are numerous, chief among them being the dolmen of Fontanaccia in the arrondisse ment of Sartene. (X.) Although as an archaeological field Corsica is little explored, the excavations of C. J. Forsyth Major, E. Passemard and H. Obermaier have been sufficiently thorough to demonstrate that it is in a high degree improbable that man existed in Corsica be fore the late Stone Age (neolithic) or even the beginning of the Metal Era. The first civilization that can be recognized has marked Ligurian affinities and was probably derived from across the gulf of Genoa. It is represented by a meagre outfit of small stone tools (including some of jasper and obsidian), ornaments of stone, shell, and bone, and occasional bronze weapons and trinkets. Finds of this nature occur, although rarely, in rock shelters and caves; thus, near Bonifacio contracted skeletons with a stone slab over the head only (a Ligurian burial-fashion)' were accompanied by obsidian scrapers and potsherds. Probably the megalithic burial-places (stazzone), rectangular stone Gists about 'oft. in length and roofed by a single slab, belong to this same cul ture; but although about 15 are known and although stone imple ments have been picked up near them, their exact chronological position is unknown. These cists are all ruined ; one is situated a little to the west of Corte, but the remainder are grouped either in the extreme north, or in the south-west, of the island. A large number (over 4o) of menhirs (stantari), sometimes grouped in alignments, are also found in the same districts as the cists, and are probably contemporary with the tombs. A "camp" with a massive stone rampart is also recorded at Ficciaggola near Ajac cio ; but its date is uncertain.

The sculptured menhirs, of which four or five are known, are of considerable interest. They are distinguished from the French series of statue-menhirs by the fact that the head, chin, and neck, are shaped, though often very roughly. The best known is the Statue d' Apricciani, which has been called Phoenician; but the most interesting is the Statue of Petra-Pinzuta, for this shows a version of the girdle and baldrick common in the French carvings.

The Ligurian civilization was probably long-lived. There is evidence, however, of the altered Iron Age (Hallstatt) fashions in the important Gravona hoard of bronzes, and in the Cagnano cemetery near Luri that probably dates from 700-600 B.C. More over, about 56o B.C. the Phocaean Greeks founded a colony at Alalia; but the Greek occupation was not a long one, and after the naval battle in 535 between the Greeks and the allied fleets of Carthage and Etruria, the colony was abandoned. Some red figure pottery found in the island may date from the Greek settle ment; there is also enough Etruscan ware to suggest that after the Greeks left Alalia the Etruscans to a certain extent took their place, though Carthage thenceforward claimed the island until it was ceded to Rome in the early part of the 3rd century B.C. The Roman occupation had doubtless a larger general effect on native life, and a number of Roman buildings are still to be seen, particularly at Aleria.

AUTHORITIES.-E. Passemard, L'Homme prehistorique, 13e ann. Authorities.-E. Passemard, L'Homme prehistorique, 13e ann. (1926), 199; C. J. Forsyth Major, IXe Congres Int. de Zoologie, Monaco (1913) , P. 594 ; R. Lucerna, Abhandlgn. der k.k. Geograph ischen Gesellsch. in Wien, IX. (191o) ; H. Obermaier, Ebert's Real lexikon der Vorgeschichte, s.v. "Korsika." For the megaliths, A. de Mortillet, Nouvelles Arch. des Missions scient. et litt., III. 51; L. Giraux, L'Homme prehist., se ann. (19o3), 262 ; 13e ann. (1926), 246; for the statue-menhirs, L. Giraux, loc. cit., and Et. Michon, Rec. des mem. Soc. des Antiquaires de France, Centenaire (1904) , P. 299. Generally, see Prosper Merimee, Notes d'un voyage en Corse (1840) ; F. von Duhn, Italische Graberkunde (Heidelberg, 1924), p. 112. For the Cagnano cemetery, E. Chantre, C.R. 3oe sess. de l'Assoc. f rancaise pour l'avancement des Sciences (Ajaccio, 1901), II. 715, and for the Gravona hoard, Bull. Soc. Prehist. Francaise (1924), XXI. 224. For the later periods, Th. Mommsen, Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, X. II. 838. (T. D. K.) The earliest inhabitants of Corsica were probably Ligurian, but the Phocaeans of Ionia were the first civilized people to estab lish settlements. About 56o B.C. they landed in the island and founded the town of Alalia. Their power soon dwindled before that of the Etruscans, who were in their turn driven out by the Carthaginians. The latter were followed by the Romans, who gained a footing in the island at the time of the First Punic War, but did not establish themselves there till the middle of the 2nd century B.C. In the early centuries of the Christian era Corsica formed one of the senatorial provinces of the empire, and was used as a place of banishment for political offenders. One of the most distinguished of those was the younger Seneca, who spent in exile there the eight years ending A.D. 49.

During the break-up of the Roman empire in the West, Corsica was disputed between the Vandals and the Gothic allies of the Roman emperors, until in 469 Gaiseric finally made himself master of the island. For 65 years the Vandals maintained their domination, the Corsican forests supplying the wood for the fleets with which they terrorized the Mediterranean. After the destruction of the Vandal power Corsica became part of the East Roman empire. Thereafter Goths and Lombards in turn ravaged the island, the rule of the Byzantines being effective only in grind ing excessive taxes out of the wretched population; to crown all, in 713 the Muslims from the northern coast of Africa made their first descent. Corsica remained nominally attached to the East Roman empire until Charlemagne conquered it. Moorish incur sions from Spain soon followed, and in 810 the Moors gained temporary possession. Though expelled they returned again and again, and in 828 the defence of Corsica was entrusted to Boniface II., count of the Tuscan march. He built a fortress in the south of the island which formed the nucleus of the town (Bonifacio) that bears his name. Boniface's war against the Saracens was continued by his son, but the Muslims seem to have remained in possession of part of the island until about 93o.

Terra di Comune.—Later the period of feudal anarchy be gan, a general conflict of petty lords each eager to expand his domain. The counts of Cinarca (to the north-east of Ajaccio), especially aimed at establishing their supremacy over the whole island. To counteract this and similar ambitions, in the I I th cen tury, a sort of national diet was held, and Sambucuccio, lord of Alando, put himself at the head of a movement which resulted in confining the feudal lords to the southern part of the island and in establishing in the rest, henceforth known as the Terra di Comune, a sort of republic composed of autonomous parishes. Each parish or commune nominated a certain number of council lors who, under the name of "fathers of the commune," were charged with the administration of justice under the direction of a podesta, who was as it were their president. The podestas of each of the States or enfranchised districts chose a member of the supreme council charged with the making of laws and regula tions for the Terra di Comune. This council or magistracy was called the Twelve, from the number of districts taking a share in its nomination. In each district the fathers of the commune elected a magistrate who, under the name of caporale, was en trusted with the defence of the interests of the poor and weak. The constitution thus established has never lost its hold on the affections of the people.

Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction.—Meanwhile the south remained under the sway of the counts of Cinarca, while in the north feudal barons maintained their independence in the promontory of Cape Corso. Towards the end of the century the popes laid claim to the island; the Corsican clergy supported the claim, and in 1077 the Corsicans declared themselves subjects of the Holy See in the presence of the apostolic legate Landolfo, bishop of Pisa. Pope Gregory VII. thereupon invested the bishop and his succes sors with the island and the Pisans took solemn possession, their "grand judges" (judices) replacing the papal legates. Corsica, valued by the Pisans as by the Vandals as an inexhaustible store house of materials for their fleet, flourished exceedingly under the enlightened rule of the great commercial republic. Causes of dissension remained, however, abundant. The Corsican bishops repented their subjection to the Pisan archbishop; the Genoese intrigued at Rome to obtain a reversal of the papal gift to the rivals with whom they were disputing the supremacy of the seas. In 1138 Innocent II. divided the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the island between the archbishops of Pisa and Genoa. This gave the Genoese great influence in Corsica, and the contest be tween the Pisans and Genoese began. It was not, however, till 1195 that the Genoese, by capturing Bonifacio—a nest of pirates preying on the commerce of both republics—actually gained a footing in the country.

Throughout the 13th century the struggle between Pisans and Genoese continued, reproducing in the island the feud of Ghibel lines and Guelphs that was desolating Italy. Pope Boniface VIII. added to the complication by investing King James of Aragon with the sovereignty of Corsica and of Sardinia. In 1325 the Aragonese attacked and reduced Sardinia, with the result that the Pisans, their sea-power shattered, were unable to hold their own in Corsica. A fresh period of anarchy followed until, in a great assembly of caporali and barons decided to offer the sov ereignty of the island to Genoa. A regular tribute was to be paid to the republic ; the Corsicans were to preserve their laws and customs, under the Council of Twelve in the north and a Council of Six in the south ; Corsican interests were to be represented at Genoa by an orator.

Genoese Domination.

The Genoese domination thus in augurated began under evil auspices—for the Black Death killed off some two-thirds of the population—and was not destined to bring peace. The feudal barons of the south and the hereditary caporali of the north alike resisted the authority of the Genoese governors; and King Peter of Aragon took advantage of their feuds to reassert his claims. Among the events of a confused and troubled period may be mentioned the founding of Bastia, in 1383, by Leonello Lomellino, a Genoese governor and count of Corsica. This, with other coastal strong places, such as Calvi and Bonifacio, was a bulwark of Genoese power, though it was lost to the Aragonese at times. By 1447 the position was that the Genoese were masters of the strongholds, the lords of Cinarca held the lands in the south, under the nominal suzerainty of Aragon, and Galeazzo da Campo Fregoso, a member of a power ful Genoese family, was supreme in the Terra di Comune.

The Bank of San Giorgio.

An assembly of the chiefs of the Terra di Comune decided to offer the government of the island to the Company or Bank of San Giorgio, a powerful com mercial corporation established at Genoa in the i4th century. The bank accepted; the Spaniards were driven from the country ; and a government was organized. Further trouble soon broke out, however, with conflicts between rival lords, and it was not till i5II that the bank could consider itself in secure possession of the island.If the character of the Corsicans has been distinguished in modern times for a certain wild intractableness and ferocity, the cause lies in their unhappy past, and not least in the character of the rule established by the Bank of San Giorgio. The power which the bank had won by ruthless cruelty, it exercised in the spirit of the narrowest and most short-sighted selfishness. Only a shadow of the native institutions was suffered to survive, and no adequate system of administration was set up in the place of that which had been suppressed. In the absence of justice the blood-feud or vendetta grew and took root in Corsica just at the time when, elsewhere in Europe, the progress of civilization was making an end of private war. The agents of the bank, so far from discouraging these internecine quarrels, looked on them as the surest means for preventing a general rising. Concerned, moreover, only with squeezing taxes out of a recalcitrant popula tion, they neglected the defence of the coast, along which the I3arbary pirates harried and looted at will; and to all these woes were added, in the i6th century, pestilences and disastrous floods, which tended still further to impoverish and barbarize the country.

In these circumstances King Henry II. of France conceived the project of conquering the island. Three years' confused fighting from 1553 to 1556 ended in the conclusion of a truce which left Corsica—with the exception of Bastia—in the hands of the French, who proceeded to set up a tolerable government. In '559, however, the) island was restored to the Bank of San Giorgio, from which it was at once taken over by the Genoese republic.

Genoese Rule Restored.

Trouble at once began again. The Genoese attempted to levy a tax which the Corsicans refused to pay; and in violation of the terms of the treaty they confiscated the property of Sampiero da Bastelica, the Corsican national hero, who had put himself at the head of the national movement. , The suzerainty of the Turk seemed preferable to that of Genoa, and, with letters from the king of France, Sampiero went to Constantinople to ask the aid of a fleet for the purpose of reduc ing Corsica to the status of an Ottoman province. All his efforts to secure foreign help were, however, vain: he determined to act alone, and in June 1564 landed at Valinco with only 5o follow ers. His success was at first extraordinary, and he was soon at the head of 8,000 men; but ultimate victory was rendered impos sible by the internecine feuds of which the Genoese well knew how to take advantage. For over two years a war was waged in which quarter was given on neither side; but after the assassina tion of Sampiero in 1567 the spirit of the insurgents was broken, and peace was declared in 1568.From this time until 1729 Corsica remained under the gov ernment of Genoa, in a peace due to lassitude and despair rather than contentment. The settlement of 1568 had reserved a large measure of autonomy to the Corsicans; during the years that followed this was withdrawn piecemeal, until, disarmed and power less, they were excluded from every office in the Administration.

The vendetta increased; in the absence of effective protection the sea-board was exposed to the ravages of the Barbary pirates, so that the coastal villages and towns were abandoned and the inhabi tants withdrew into the interior, leaving the most fertile part of the country to fall into the condition of a malarious waste. To add to all this, in 1576 the population had been decimated by a pestilence. Emigration en masse continued, and an attempt to remedy this by introducing a colony of Greeks in 1688 only added one more element of discord to the luckless island. To the Genoese Corsica continued to be merely an area to be exploited for their profit; they monopolized its trade; they taxed it up to and beyond its capacity; they made the issue of licences to carry firearms a source of revenue, and therefore studiously avoided interfering with the custom of the vendetta.

King Theodore of Corsica.

In 1729 the Corsicans, irritated by a new hearth-tax, rose in revolt. As usual, the Genoese were soon confined to a few coast towns; but the intervention of the emperor Charles VI. and the despatch of a large force of Ger man mercenaries turned the tide of war, and the authority of Genoa was temporarily re-established. A fresh outbreak soon took place, but lack of arms and provisions made any decisive success of the insurgents impossible, and when, on March 12, 1736, the German adventurer Baron Theodor von Neuhof arrived with a shipload of muskets and stores and the assurance of further help to come, leaders and people were glad to accept his aid on his own conditions, namely that he should be acknowledged as king of Corsica. The new king's reign was not fated to last long. The opera bouffe nature of his entry on the stage--he was clad in a scarlet caftan, Turkish trousers and a Spanish hat and feather, and girt with a scimitar—did not, indeed, offend the unsophisticated islanders; they were even ready to take seriously his lavish bestowal of titles and his knightly order "della Libera zione" ; they appreciated his personal bravery; and the fact that the Genoese Government denounced him as an impostor and set a price on his head only confirmed him in their affection. But it was otherwise when the European help that he had promised failed to arrive, and, the Governments with which he had boasted his influence disclaimed him. In November he lef t the island, never to return. The Corsicans, weary of the war, opened nego tiations with the Genoese; but the refusal of the latter to regard the islanders as other than rebels made a mutual agreement impos sible. Finally Genoa decided to seek the aid of France.

Sardinian and British Intervention, 1746.

The object of the French in assisting the Genoese was not the acquisition of the island for themselves so much as to obviate the danger, of which they had long been aware, of its falling into the hands of another Power, notably Great Britain. The Corsicans, on the other hand, though ready enough to come to terms with the French king, refused to acknowledge the sovereignty of Genoa even when backed by the power of France. The French did, how ever, succeed in restoring order. But this depended on the pres ence of their troops which were withdrawn in 174o, leaving the Genoese and Corsicans to begin the perennial struggle anew.The Corsicans made a vigorous onslaught on the Genoese strongholds, helped by the sympathy and active aid of European Powers. In 1746 Count Domenico Rivarola, a Corsican in Sar dinian service, succeeded in capturing Bastia and San Fiorenzo with the aid of a British squadron and Sardinian troops. The factious spirit of the Corsicans themselves was, however, their worst enemy. The British commander judged it inexpedient to intervene in the affairs of a country of which the leaders were at loggerheads; Rivarola, left to himself, was unable to hold Bastia —a place of Genoese sympathies—and in spite of the collapse of Genoa itself, now in Austrian hands, the Genoese governor succeeded in maintaining himself in the island. By the time of the signature of the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, in 1748, the situa tion of the island had again changed. Owing to a report that the king of Sardinia was meditating a fresh attempt to conquer the island, a strong French expedition had, at the request of the republic, occupied Calvi, Bonifacio, Ajaccio and Bastia. By the terms of the treaty Corsica was once more assigned to Genoa, but the French garrison remained, pending a settlement between the republic and the islanders. In view of the intractable temper of the two parties no agreement could be reached, and the with drawal of the French troops was the signal for a fresh rising. The usual faction disputes followed till, in 1755, the Corsican hero Pasquale Paoli was invited to come from Naples and assume the command.

Pasquale Paoli.

The first task of Paoli, elected general in April at an assembly at San Antonio della Casabianca, was to suppress a rival faction. By the spring of 1756 this was done, and the Corsicans were able to turn a united front against the Genoese. At this juncture the French, alarmed by a supposed understanding between Paoli and the British, once more inter vened, and occupied Calvi, Ajaccio and San Fiorenzo until In 1758 Paoli renewed the attack on the Genoese, founding the new port of Isola Rossa as a centre whence the Corsican ships could attack the trading vessels of Genoa. The republic, indeed, was now too weak to attempt seriously to reassert its sway over the island, which, with the exception of the coast towns, Paoli ruled with absolute authority and with conspicuous wisdom. In the intervals of fighting he was occupied in reducing Corsican anarchy into some sort of civilized order. The vendetta was put down, partly by religious influence, partly with a stern hand ; the surviving oppressive rights of the feudal lords were abolished; and the traditional institutions of the Terra di Comune were made the basis of a democratic constitution for the whole island.All now depended on the attitude of France to which Power both Paoli and the republic made overtures. In 1764 a French expedition arrived, and garrisoned three of the Genoese fortresses. French and Corsicans remained on amicable terms, and the in habitants of the nominally Genoese towns actually sent repre sentatives to the national consulta or parliament. In 1767 the Corsicans captured the Genoese island of Capraja, and occupied Ajaccio and other places evacuated by the French as a protest against the asylum given to the Jesuits exiled from France. Genoa now recognized that she had been worsted in the long contest, and on May 15, 1768, signed a treaty selling the sovereignty of the island to France.

The Corsicans, intent on independence, were now faced with a more formidable enemy than the decrepit republic of Genoa. A section of the people, indeed, were in favour of submission; but Paoli himself declared for resistance ; and among those who supported him at the consulta summoned to discuss the question was his secretary Carlo Buonaparte, father of Napoleon Bona parte, the future emperor of the French. In the absence of the hoped-for help from Great Britain the issue of the resultant war could not be doubtful ; and by the summer of 1769 the French were masters of the island. On June 16 Paoli and his brother with some 400 of their followers embarked on a British ship for Leg horn. On Sept. 15, 177o, a general assembly of the Corsicans was called, the deputies swearing allegiance to King Louis XV.

Corsica and the Revolution of 1789.

For 20 years Corsica, while preserving many of its old institutions, remained a depend ency of the French Crown. Then came the Revolution, and the island was incorporated in France as a separate department. Paoli, recalled from exile by the National Assembly on the motion of Mirabeau, of ter a visit to Paris, where he was ac claimed as "the hero and martyr of liberty," returned in 1790 to Corsica, where he was received with immense enthusiasm as `father of the country." With the new order in the island, however, he was in little sympathy. In the towns branches of the Jacobin Club had been established, and these tended to usurp the functions of the regular organs of government and to intro duce a new element of discord into a country which it had been Paoli's life's work to unify. Suspicions of his loyalty to revolu tionary principles had been spread at Paris so early as 1791 ; yet in 1792 he was appointed lieutenant-general of the forces and governor (capo comandante) of the island. With the men and methods of the Terror, however, he was wholly out of sympathy. Called, in 1793, to the bar of the Convention, he replied by sum moning the representatives of the communes to meet in diet at Corte on May 27, when he stated that he was rebelling, not against France, but against the dominant faction of whose actions the majority of Frenchmen disapproved. In consequence Paoli and his sympathizers were declared by the Convention hors la loi (June 26).Paoli had already made up his mind to raise the standard of revolt against France. But though the consulta at Corte elected him president, Corsican opinion was by no means united. Na poleon Bonaparte indignantly rejected the idea of a breach with France, and the Bonapartes were henceforth ranked with his enemies. Paoli now appealed for assistance to the British Gov ernment, which despatched a considerable force. By the summer of 1794, after hard fighting, the island was reduced, and in June the Corsican assembly formally offered the sovereignty to King George III. The British occupation lasted two years, the island being administered by Sir Gilbert Elliot. Paoli, whose presence was considered inexpedient, was invited to return to England, where he remained till his death. In 1796 Bonaparte, after his victorious Italian campaign, sent an expedition against Corsica. The British, weary of a somewhat thankless task, made no great resistance, and in October the island was once more in French hands. It was again occupied by Great Britain for a short time in 1814, but in the settlement of 1815 was restored to the French Crown. Its history henceforth is part of that of France.