Cosmogony

COSMOGONY is in common language a theory, hypothesis or speculation as to the origin of the earth, sun, moon and stars. Such speculations are frequently produced by primitive races in their myth-making stage of development, and may be subse quently expanded and systematized by poets, priests and philoso phers. In more scientific language cosmogony is the science which studies the formation of the earth, sun, moon and stars under the action of natural laws. Astronomy gathers information as to the structure of the heavens and the present state of the heavenly bodies; the province of cosmogony is to explain how these heaven ly bodies come to be where they are and as they are ; it takes the still photograph presented by astronomy and tries to develop it into a cinematograph film which shall exhibit the universe being born, developing, passing through its present stage, ageing and decaying before our eyes, the relation of each picture to the succeeding one being that of cause and effect.

Ancient Cosmogonies.

In contrast with modern scientific cosmogony, the crude cosmogonies of primitive races generally contain no conception of gradual or evolutionary change. For the most part they postulate a simple creative act ; a crow or a raven or a tortoise or a magnified old man takes raw material and, as the result of a single effort, fashions the earth and the heavenly bodies in precisely the shape and form in which they exist to-day. At the best the act of the creator is merely that of shaping, carving and building ; at the worst it may be even less than this, as for instance in the cosmogony of the Thlinkit Indians, where the creator-hero steals the sun, moon and stars out of a box in which they had lain hidden, and hangs them up so that they illuminate the earth. In the cosmogonies of more re flective races, especially those of India, the act of creation may be accomplished by a mere thought of the creator ; from being a vision in his mind the world suddenly bursts into being as a material fact. The Iranian account of creation was especially interesting and somewhat akin to that in Genesis.We owe to the Greeks the most beautiful, richest and most imaginative cosmogony that existed before science came to re place poetic imaginings by an effort to unravel the actual facts of creation. Uranus, the most ancient of all the gods, founded a dynasty in heaven, and he and his sons and his sons' sons through three generations took part in creating the world and peopling it with the minor immortals whose function was to help the world on its way in the events of everyday life.

Six centuries before Christ, Thales of Miletus challenged this mythology, which he derided as being too anthropomorphic, and cosmogony passed from the province of the poets and mystics to that of the philosophers. Two centuries later Empedocles taught that all things were formed out of the union in different propor tions of the four eternal, indestructible and unchangeable elements of fire, air, earth and water, and Plato wrote that the heavenly bodies, the earth, sun, moon and stars, as well as all animals and plants, have been created out of those four absolutely inanimate elements, "not from any action of mind or of any god, or by any art, but by the action of chance and of the forces arising out of certain inherent affinities among the natural bodies, hot tending to combine with cold, dry with moist, soft with hard and so on." Newton's Cosmogony.—Cosmogony advanced but little be yond the stage of philosophic speculation until Newton taught to the world the meaning of the universal applicability of natural laws. The force which causes the apple to fall to the ground also keeps the moon in its orbit, and the forces which govern the simple phenomena of our daily lives must have acted at, and may alone have sufficed for, the creation of the earth and the heavenly bodies. In 1692 we find him writing to Bentley, Master of Trinity college, Cambridge, as to the possible influence of gravi tation in the formation of worlds : "It seems to me that if the matter of our sun and planets, and all the matter of the universe, were evenly scattered through out all the heavens, and every particle had an innate gravity to wards all the rest, and the whole space throughout which this mat ter was scattered was finite, the matter on the outside of this space would, by its gravity, tend towards all the matter on the inside, and by consequence fall down into the middle of the whole space, and there compose one great spherical mass. But if the matter were evenly disposed throughout an infinite space, it could never con vene into one mass, but some of it would convene into one mass and some into another, so as to make an infinite number of great masses, scattered great distances from one another throughout all that infinite space. And thus might the sun and fixed stars be formed, supposing the matter were of a lucid nature." Kant's Cosmogony.—In 1755 Kant followed Newton in re garding a limitless waste of chaotic primordial matter as the raw material out of which the universe has been formed, as also in supposing gravity to be the agency through which this formation took place. He imagined that, as a result of their mutual gravita tional attractions, the primaeval atoms continually fell in upon one another, and in so doing became hotter just as the bullet becomes hot on striking the target.

This is in keeping with modern scientific knowledge, but Kant's next step was not. For he imagined that the collisions of his atoms generated not only heat but also rotation. As the atoms collided the nebula not only got hotter and hotter, but also, he thought, began to rotate and spun faster and faster until at last splashes of matter were thrown off from its equator much in the manner in which splashes of mud are thrown off a bicycle wheel. These splashes of matter formed a continuous rotating ring which encircled the nebula just as Saturn's rings encircle Saturn. The ring finally condensed into a planet and by many repetitions of the process the sun's family of planets was born out of his body.

Laplace's Nebular Hypothesis.

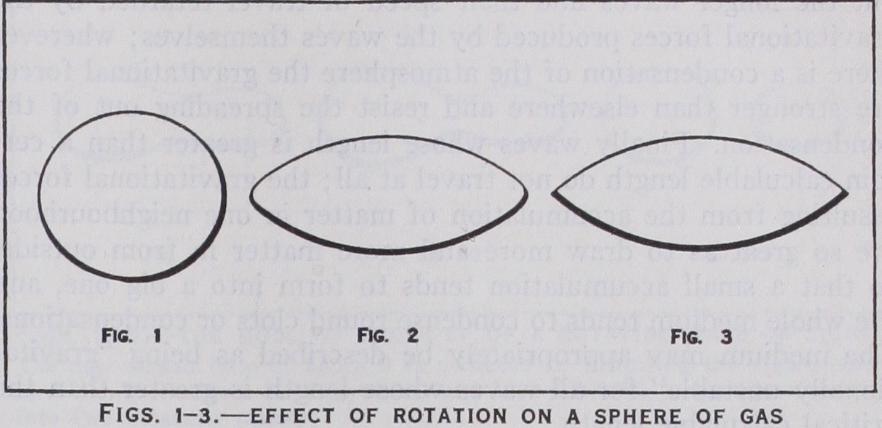

In 1796 Laplace pro pounded the system of cosmogony which, under the general name of the "nebular hypothesis," held the field for a full century. Laplace's cosmogony may be briefly described as that of Kant with the mistakes left out. Apart from these, the two theories are almost identical, although Laplace seems to have written in complete ignorance of the earlier speculations of Kant. Avoiding Kant's error of imagining that rotation could be generated out of no rotation, Laplace took as his raw material a nebula which was already endowed with a certain amount of rotation. He imagined this riebula to be continually emitting radiation, and theref ore to cool and to shrink as it cooled. By a well-knoirn scientific prin ciple, "the Conservation of Angular momentum," a body which is spinning and at the same time shrinking in size must spin faster as it shrinks, at any rate unless some outside agency is at work checking or inhibiting the increase in its rate of spin. Laplace accordingly supposed the nebula to rotate ever faster and faster about its axis.The theory of the dynamics of rotating bodies makes it clear that a mass of either liquid or gas in rotation cannot rest in the spherical shape which it would assume if it were not rotating. Under slow rotation such a mass assumes the shape of a slightly flattened oblate spheroid, or, if we prefer so to describe it, a body which differs from a sphere only in bulging a bit round its equator and being a bit flattened at its poles—an orange-shaped figure. The shape is that of the earth and the other planets, which have assumed this shape precisely on account of their rotation. A ship at the earth's equator is farther from the centre of the earth than a ship at the north pole, and if the earth's rotation were suddenly checked, the path from equator to pole would be seen to be a downhill path, down which not only ships, but also oceans, cities and continents would start to slide, and would con tinue sliding until the earth's equatorial bulge disappeared and the earth's shape had become entirely spherical. Thus it is the earth's rotation which keeps its equatorial bulge in existence.

In the same way if the earth's present speed of rotation were increased, ice, water, earth and other bodies would start to slide from the poles to the equator, thereby increasing the equatorial bulge, so that the earth's figure would become more flattened than it now is. Mathematical analysis shows that any increase in the speed with which a gravitating mass of liquid or gas rotates in creases its flatness of figure. So long as the rotation is slow, this figure has the shape of an oblate spheroid such as the earth, but with faster rotation the spheroidal shape is lost.

When this occurs, it can be shown that the increased rotation produces changes which are of the same general nature in all bodies, provided only that their mass is sufficiently condensed towards the centre. As the spheroidal shape is departed from, the equator of such bodies pulls out into a pronounced edge which ultimately becomes perfectly sharp, so that the body acquires the shape of a double convex lens. The sequence of figures is shown in figs. 1-3.

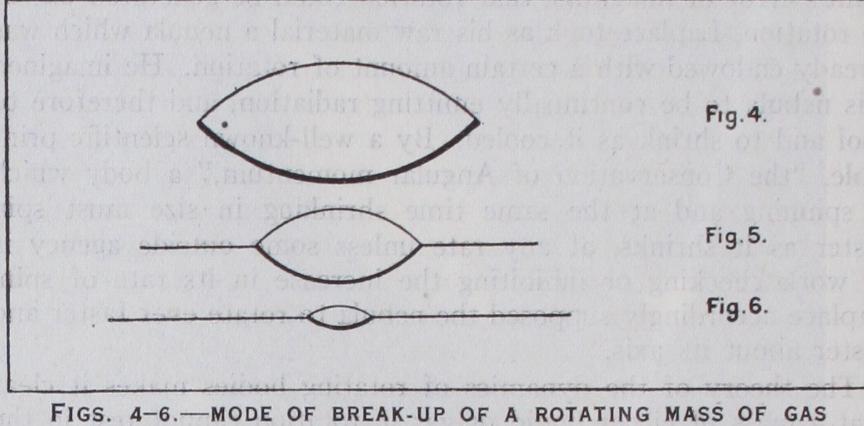

Mathematical theory further shows that when once the lens Shaped figure has been attained, any further increase in the speed of rotation results in matter being thrown off from the sharp equator. The mass is now rotating so fast that its gravitational attraction is inadequate to retain the outermost particles on the equator against the centrifugal tendency set up by rotation, and they are thrown off into space. No matter how much the rotation is increased, the sequence of events remains the same. At each stage the sharp edge acts like a safety-valve, ejecting just so much matter as is necessary in order that the remainder may be able to rotate as a lenticular mass with a sharp edge.

A fair analogy is to be found in the sequence of events when a tumbler partially filled with water is placed on a rotating table, which is then made to spin faster and faster. As the speed of rotation increases the water creeps up the side of the glass until it reaches the rim, after which any further increase of rotation is accommodated by the water spilling over the edge of the glass. In the cosmogonical problem the lens-shaped figure corresponds to the glass with water exactly up to its rim; the matter ejected from the sharp equator of the lens is the matter spilled out when the rotation became too great for all the matter to stay inside the lens-shaped boundary. After this spilling-out process has once begun the sequence of figures is that shown on p. 490, fig. 4, which is identical with the previous fig. 3, being repeated for the sake of continuity.

Laplace believed that stars such as the sun which have given birth to families of planets had at some stage of their existence passed through the sequence of configurations just described, and supposed the planets to have been formed by the condensation of the matter which had been spilled out in the equatorial plane. This, of course, explained why the planets all moved in approxi mately the same plane and revolved in the same direction round the sun. He further supposed that when once the planets had condensed and been set free as independent bodies they went through precisely the same process in their turn, thus becoming surrounded with families of satellites, which necessarily revolved in the equatorial planes of the planets in the same direction in which they themselves revolved round the sun.

For a long time this hypothesis appeared to give the most likely ex-planation of the origin of the solar system, but to-day the available evidence both of observational astronomy and of mathe matical theory is unfavourable to the explanation. The sky pro vides a great number of examples of the fate awaiting stars which rotate too fast for safety; it is not to found a family but to break in two. And when the mathematician follows out the details of the process. imagined by Laplace with reference to the special case of the solar system, he finds that there is nothing wrong with the general mathematical theory, but that its application to the solar system leads to numerical values which cannot possibly be reconciled with those observed. Thus there is a consensus of opinion that Laplace's hypothesis must be abandoned as an explanation of the origin of the solar system, not because it is wrong in theory, but because it fails in practice.

If, however, the process imagined by Laplace is correct in theory it may be that it occurs elsewhere in the universe; if it has not formed the solar system it may perchance have been responsible for some other formation known to the astronomer. In actual fact it seems almost certain that the process imagined by Laplace is continually in progress, but on a stupendous scale which is incomparably greater than any of which Laplace ever dreamed.

Gravitational Instability.

Let us return to Newton's con ception of an enormous mass of nebular matter scattered, in the first instance, uniformly through space. Newton conjectured that distinct condensations would form in such a medium, and that in time all the nebular matter would settle round these conden sations under the influence of gravity. The problem has been discussed mathematically by Jeans, who has confirmed the general accuracy of Newton's conjecture, and has also obtained a formula from which it is possible to calculate the average distance apart at which the condensations will form in any given nebular medium, and the average mass that will ultimately settle down round each.When a disturbance is produced in the earth's atmosphere, as for instance by firing a gun, waves of sound carry the energy of the disturbance to great distances in the form of waves of alter nate condensation and rarefaction, the rate of travel being the same for waves of all wave-lengths. Let us now imagine an atmosphere or other mass of gas extending for millions of millions of miles, and disturbances of wave-length millions and millions of times as great as that of terrestrial sounds—let us, in brief, imagine phenomena on the astronomical instead of on the terres trial scale of magnitude. The gravitational attraction of the various parts of the atmosphere on one another now becomes very important, and shows its importance by causing waves of different wave-lengths to travel at different speeds. The waves of short wave-length all travel at the same speed, this being the speed at which they would travel if gravitation were non-existent, but the longer waves find their speed of travel retarded by the gravitational forces produced by the waves themselves ; wherever there is a condensation of the atmosphere the gravitational forces are stronger than elsewhere and resist the spreading out of the condensation. Finally waves whose length is greater than a cer tain calculable length do not travel at all; the gravitational forces resulting from the accumulation of matter in one neighbourhood are so great as to draw more and more matter in from outside, so that a small accumulation tends to form into a big one, and the whole medium tends to condense round clots or condensations. The medium may appropriately be described as being "gravita tionally unstable" for all waves whose length is greater than the critical calculable length.

The average distance apart of the clots which will form in such a medium is equal to the wave-length of the shortest waves which are gravitationally unstable. This distance can be calculated when two quantities are known, namely, the density and the tempera ture of the gaseous or nebular medium. Now if, as Newton imagined, "all the matter of the universe were evenly scattered throughout the heavens," we should obtain a medium whose density Dr. Edwin Hubble of Mount Wilson observatory has recently estimated would be of the order of grammes per cu. centimetre, a density at which there would only be about one molecule to every i,000cu.yd. The principle of gravitational instability shows that such a medium would condense into clots, but if the gas were initially at a fairly high temperature the average amount of matter in each clot would be hundreds or even thousands of millions of times as great as the amount of matter in the sun or in the average star.

The process cannot, then, result as Newton thought in the for mation of the sun and fixed stars; it must produce bodies on an altogether grander scale.

Spiral and other Extra-galactic Nebulae.

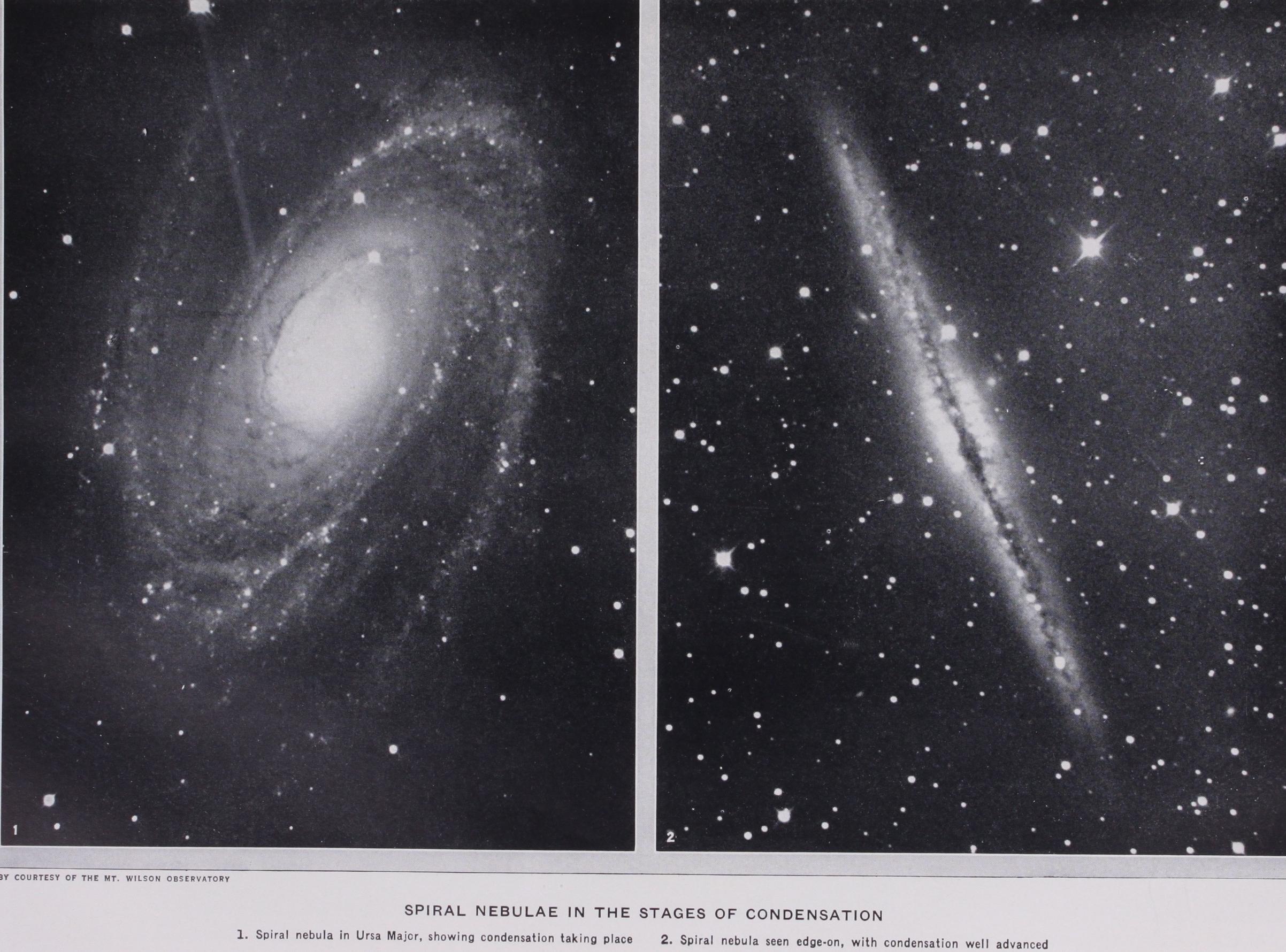

The astrono mer is familiar with bodies of the required size; they are the spiral and other extra-galactic nebulae. The sun and all the stars we can see with the naked eye belong to a single colony of stars, the "galactic system," which is bounded by the milky way alto gether. Outside this system lie the bodies known as "extra galactic nebulae," at distances so great that light from even the nearest of them, although covering i 86,000m. every second of its journey, takes something like I,000,000 years to reach us. The masses of these nebulae are of the order of ion or I,000 million times the mass of the sun, and so are of precisely the magnitude required by the hypothesis that they have been formed by gravi tational instability out of a continuous primaeval gaseous medium. Their dimensions are comparable with the dimensions of the whole galactic system, and are so enormous that, in spite of their immense distance, the astronomer can study their shapes and photograph their general appearance with comparative ease. A selection of photographs is shown in Plate II.It will be seen that the sequence of figures shown in the first four examples is precisely that shown in the theoretical figs. 4 to 6. The series could easily be extended to include observed nebulae of the shapes shown in the theoretical diagrams i and 2, but such nebulae are not interesting objects photographically. Statistical researches by Hubble make it highly probable that there is a continuous sequence of nebulae having the shapes shown in the theoretical diagrams r to 6, only the last half of this series being exemplified by the photographs shown in Plate I. The last photo graph of all on this plate shows a nebula of the same general type viewed from another angle; there is little room for doubt that this nebula is physically very similar to that shown in fig. 5, the difference in appearance arising solely from the different angle of view.

The parallelism in the two sets of figures is so marked that it seems clear that the extra-galactic nebulae must be rotating masses of the general type discussed by Laplace, except for being on an immeasurably greater scale. This interpretation is confirmed by the fact that a number of these nebulae have been found observationally to be in rotation about their shorter axes, precisely as demanded by theory. We may suppose that the original primaeval nebular medium was not completely at rest but was disturbed by currents ; as it condensed into detached nebulae the motion of the currents would persist in the form of rotation of the nebulae, the different shapes of the present nebulae representing different degrees of rotation.

The Birth of Stars.

The amount of rotation of some of the nebulae is so great that, at some stage of their shrinkage, matter was spilled out into their equatorial plane and has remained in this plane ever since; see Plate II. for a number of instances of this formation. The matter left behind in this way would at first form a continuous nebular medium, a sort of counterpart of the parent medium out of which all the nebulae were formed, except that its density must have been some I o,000 million times as great, being of the order of io 21 instead of io 31 grammes per cubic centimetre. The process of gravitational instability must operate in this medium also, but as a consequence of the far greater density, the masses of the resulting condensations must be far less. Calculation indicates that the amount of matter in each condensation must be about equal to that in a newly-born star.This suggests very forcibly that the outer regions of the nebulae are the birth-places of the stars. Condensations in process of forming may be seen in the outer regions of the nebulae shown in Plate I., and at various times actual unmistakable stars have been photographed in the outer regions of the nearer of the extra galactic nebulae, although it is significant that all efforts to find them in the inner regions of the same nebulae have failed.

The Development of Rotating Stars.

The sequence of events after a star has come into being is still a matter of debate (see STELLAR EVOLUTION) . There is, however, general agreement that a newly-born star must contract. According to Jeans, this contraction must continue until a comparatively firm unyielding base has been formed at the centre of the star, through the atoms, nuclei and electrons being so congested that the ordinary gas laws are entirely out of operation ; he finds that in the central regions at least of the star, the density of matter must be so great that its state approximates more nearly to the liquid than to the gaseous state.The first products of gravitational instability, the extra-galactic nebulae, proved to be incomparably greater in size than Laplace's imaginary rotating nebula, but each of the smaller masses of gas formed by condensation out of the outlying parts of these nebulae is in effect a gaseous nebula of just about the size and mass imagined by Laplace. If, then, the younger generation of nebulae, as they rotate and shrink, meet with the same sequence of expe riences as their parents before them, we have the course of events postulated by Laplace taking place on the scale imagined by Laplace, and we need not look farther for the mode of birth of the solar system. But mathematical theory prohibits such a simple solution to the problem.

The gas set free from a nozzle in the laboratory does not form condensations under its own gravitation, the reason being that the mass of matter involved is so small that the gravitational attraction of the matter on itself is inappreciable ; it is only when matter is set free on a colossal scale that gravitational instability can come into operation. The scale of the galactic nebulae is amply big enough, but that of jets of gas in the laboratory is too small. Calculation shows that any ejection of gas from the equator of a rotating star is also on too small a scale for gravi tational instability to get any grip, so that the ejected gas must just scatter into space like gas out of a tap.

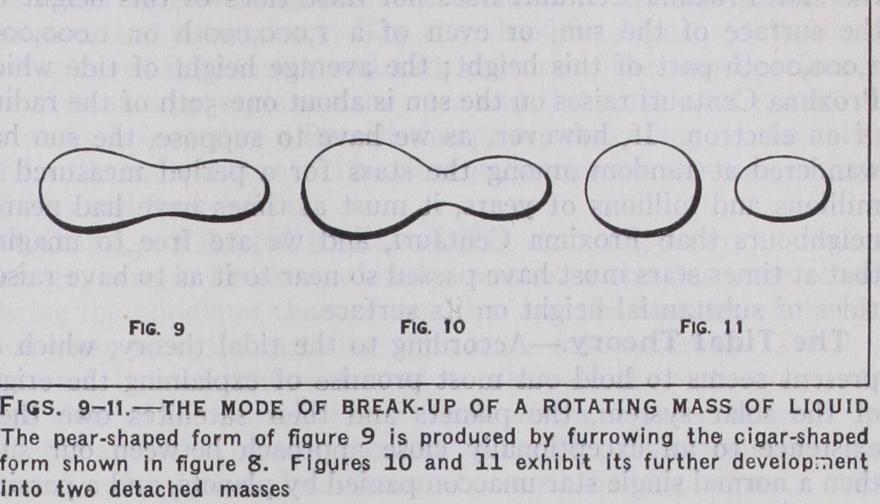

When the star has shrunk so far that its centre approximates to the liquid state, a new set of factors comes into play. The behaviour of a mass of shrinking and rotating liquid has formed the subject of investigations by many of the most eminent of mathematicians, including Maclaurin, Jacobi, Kelvin, Poincare and G. H. Darwin, and the sequence of events is now well-known. So long as the speed of rotation is low, the mass assumes the flattened orange shape already discussed. With increasing rotation the degree of flattening increases, until a stage is reached at which the shortest axis is only seven-twelfths of the longer axes. Beyond this, further shrinkage does not accentuate the flattening; instead the mass assumes the shape of an ellipsoid with three unequal axes (Jacobian ellipsoid) which continually elongates until it is shaped almost like a cigar, its length being nearly three times its shortest diameter. After passing this stage, violent fluctuations are found to be set up in the mass. It develops a waist somewhere near, but not quite at, the middle of its figure, and after a suc cession of oscillations in which this waist alternately expands and contracts, the mass ends by breaking into two.

The sequence of events is indicated in figs. 7-11, although it must be added that the last two of these figures are largely con jectural, and take us entirely beyond the reach of exact mathe matics. But there would seem to be little room for doubt that the final product of a liquid star which has shrunk while rotating is a system of two liquid stars which revolve about each other in nearly circular orbits.

Binary Stars.

Many binary systems of this type are known to astronomers, and provide confirmation of the sequence of events predicted by theory. The mere existence of systems which have broken up in the way described may be taken as evidence that the parent star was largely in a liquid state before fission occurred, since Jeans has shown that a purely gaseous star could not divide by fission into a binary system. The further develop ment of such a binary system can be calculated theoreti cally and can also be traced observationally. Three separate tendencies are at work, each acting in the direction of increasing tational forces from passing stars. These tend to increase the size of orbit of the binary, at any rate until it is of the order of or so in diameter.

The Ages of the Stars.

This last agency acts very slowly, but its effects are cumulative, and given sufficient time, it so easily overpowers the two first mentioned, that they may be disregarded by comparison. Knowing the density with which stars are scat tered in the sky, it is easy to calculate the rate at which their gravitational pulls increase the orbits of binary stars, so that the size of the orbit of a binary star gives a rough indication of its age. For most of the binaries which have been formed by fission in the way just described, this age must be reckoned in millions of millions of years.

The binary systems which can be said with fair certainty to have been formed by fission due to rapid rotation are mainly of the class known as spectroscopic binaries. The telescope generally shows these as a single point of light, but the evidence of the spectroscope reveals the fact that the apparent point of light really represents two stars describing orbits about one another. Another class of binary systems; which outnumbers these by perhaps 20 to one, consists of pairs of stars which describe orbits about each other and show visually as two distinct points of light. These are known as visual binaries. The dimensions of the orbits of many of these are so great that they can hardly have been formed by the fission of a single star and it is more likely that they are the remains of independent but adjacent condensations in the nebula from which they were born. These visual binaries provide evidence as to their ages which is in general agreement with the story told by the spectroscopic binaries.

As a rule the more massive constituent of a binary is not only brighter than the smaller constituent, but also emits more light in proportion to its mass. It is easily shown that this results in a tendency for the two masses to equalize as they diminish to gether under their emissions of radiation. Actually it is found that the constituents of older binaries approximate more closely to equality of mass than the constituents of younger binaries, and the observed ratio of mass in different types of systems gives an indication of their actual ages. Again calculation shows that average stellar ages must be reckoned in millions of millions of years.