Modern Cookery

MODERN COOKERY In its modern aspect, cookery is both an art and a science. It is an art because it requires special manipulative skill, and (2) colour, design and attractive form and service are essential, especially in the higher grades. It is a science be cause exact knowledge is necessary (I) in determining the cor rect time and amount of heat needed by the food material to be cooked to make it palatable and digestible, (2) of food values so that a rightly proportioned diet may be given, and (3) of all food stuffs so that they may be amalgamated suitably, satisfactorily and in definite and correct proportions.

Baking.

Baking is cooking in an enclosed space called an oven which may be heated by coal in a closed or open range, by gas, by oil, by electricity. The heat passes to the oven by conduction, and to the food by means of conduction and also convection (see fig. 1).(a) Baking Meat.—Joints of beef, mutton, veal, pork (see fig. 2) . General rules: A hot oven 33o ° F. for the first 10-20 min. according to the size and quality of the meat, to set the albumen and so retain the juices of the meat. Then reduce the heat and cook slowly to make the joint tender and digestible. There should be frequent basting, for the same reason. The average baking times are:— 1 5 or 20 minutes to each lb. According to the Mutton and 15 or 20 minutes over. thickness of the joint and whether Pork t 25 minutes to each lb. and solid meat or with Veal r 25 minutes over. bones.

Boned and stuffed meats 2o-25 minutes to each lb. and 2o-25 minutes over.

Foreign or chilled meat should be allowed to thaw before cook ing, or a tough joint will be the result. This may be done by hang ing for a day, or by keeping in a warm place in the kitchen—the rack over the stove for example—for several hours. Frozen meat is usually sent from the butcher already thawed, but this must be ascertained.

(b) Poultry and Game.—The same rule applies here with regard to great heat for the first ten minutes, then slow cooking. For basting, a piece of fat bacon should be put over the breast of the birds.

Average times.—For chickens 4 I hour, fowls i4 hours, small birds (i.e. plover) , 1 5-2 o min., medium birds (partridge, grouse, pigeon) 3o-45 min., pheasant 45-5o min., turkey (12 lb.) hours.

(See fig. 3.) Tough, coarse meat and old poultry should not be cooked by this method. (See sections on Boiling, Braising, Stewing.) (c) Fish.—For the baking of steaks of fish (i.e., cod, salmon) and also for the baking of rolled fillets of fish, a moderate oven is essential, owing to the delicate nature of the flesh. Average time: 3o-35 minutes according to thickness and size; for fillets I o-15 minutes. Covering with a buttered paper keeps in the flavour and ensures slow cooking.

(d) Cakes.—(I) Large rich cakes and gingerbreads need long slow cooking: rich cakes 3-6 hours, gingerbread 1 4 2 hours (according to size) . (2) The less rich pound cakes I42 hours. (3) Fruitless cakes, such as Madeira or Genoese or Sandwich, a moderate oven for about a I hour. (4) Small cakes in tins, and (5) small cakes without tins, as rock buns, scones, baking powder bread, require a quick oven for 15-2o min. (6) Swiss rolls, a quick oven for 1 o-I 5 minutes.

(e) Bread.—To stop growth of the yeast, bread must be placed in a hot oven, 340° F., and then the heat should be reduced. When cooked, there should be a hollow sound when tapped with the hand.

(f) Pastries.—The general rule for pastries is a hot oven in order to cause the starch grains in the flour to burst so that they may absorb the fat. When the pastry is thus set a cooler tempera ture is needed in order to finish cooking the meat or fruit, etc. If pastry is put into too cool an oven at first the starch grains do not swell and burst and therefore cannot absorb the fat as it melts; the result is a hard tough pastry practically minus the fat, which melts out and spills over. Therefore the richer the pastry the hotter should be the oven and if the fat is rolled into the mixture the oven should be very hot.

Short Crust.

Half fat to flour, fat incorporated by being rubbed into flour. Oven temperature 32o° F. until pastry is set.

Flaky and Rough Puff.

Two-thirds fat to flour, fat incor porated by being rolled into a dough made with the flour and water. Oven temperature to set pastry 32o° F. and then reduce to 200-290° F.

Puff Pastry.

Equal quantities of fat to flour, fat incorporated as for rough puff. Oven temperature 34o° F.

Hot Water Crust.

A hot oven at first if the pie is not in a tin or dish but standing without support, then very moderate cooking.(g) Puddings.—Including batters, usually a hot oven at first and then cooler. In baking milk puddings, for large grains and without eggs, a slow oven and long cooking is necessary to allow the grain to soften and swell and absorb the milk gradually. For small grains with egg, and for custards, again use moderate heat or the egg will curdle.

(h) Vegetables.—Marrows, tomatoes, potatoes, and many others may be baked. The temperature of the oven and time for cooking must be judged by the size, texture and age of the vege table and whether stuffed or not. A moderately hot oven is nearly always correct. Oven thermometers are not advisable, as they break and are easily put out of order. A few lessons and then ex perience should be sufficient in order to judge oven heat needed for the various foods.

Boiling.

Boiling is cooking food in very hot liquid which covers the food. Water boils at F., but although some foods are put into boiling water at first, they are cooked at a temperature between boiling point and simmering point, a temperature of 19o° F. Simmering is slow boiling. A great many foods are never ex posed to rapidly boiling liquid but only to simmering point. Boiled custard is a liquid food of eggs and milk and is erroneously named, as, if allowed to boil, the eggs would curdle—it is only brought to simmering point. In boiling, heat passes to the pan by conduction and to the food by convection currents in the water or liquid (see fig. I).I. Meat.—The general rules and average times for boiling meat are: (I) Choose a pan suitable for size of joint. (2) Use only enough water to cover joint. (3) Add salt (except for salt meats), one tablespoon to two quarts; this flavours and raises temperature of water. (4) Plunge fresh meats into boiling water and allow to boil for 3-5 min., to harden outside albumen and keep in the juices. (5) Keep at simmering point to make the meat tender. Skim well.

Add vegetables—carrot, turnip, onion—to give flavour. Salt meat and bacon must be immersed in cold water and brought quickly to boiling point. By this means the fibres toughened by salting become tender and di gestible. Allow about 2o-25 min.

to each lb., with 2o-25 min. over for fresh, meat and 25-30 min.

over for salt meat. Time must be judged by the texture, size and thickness of the joint. For joints of beef, mutton, pork, bacon, see fig. 2.

2. Poultry.—Chickens, fowls and turkeys are the only birds usually boiled. This method should be chosen for those which are old and tough. The rules are as for fresh meat, and the times as for baking. (See fig. 3b.) When meats are boiled, some of the flavour is lost in the liquid or pot liquor. For this reason vegetables are added to give flavour, and sauces are served, the pot liquor being used.

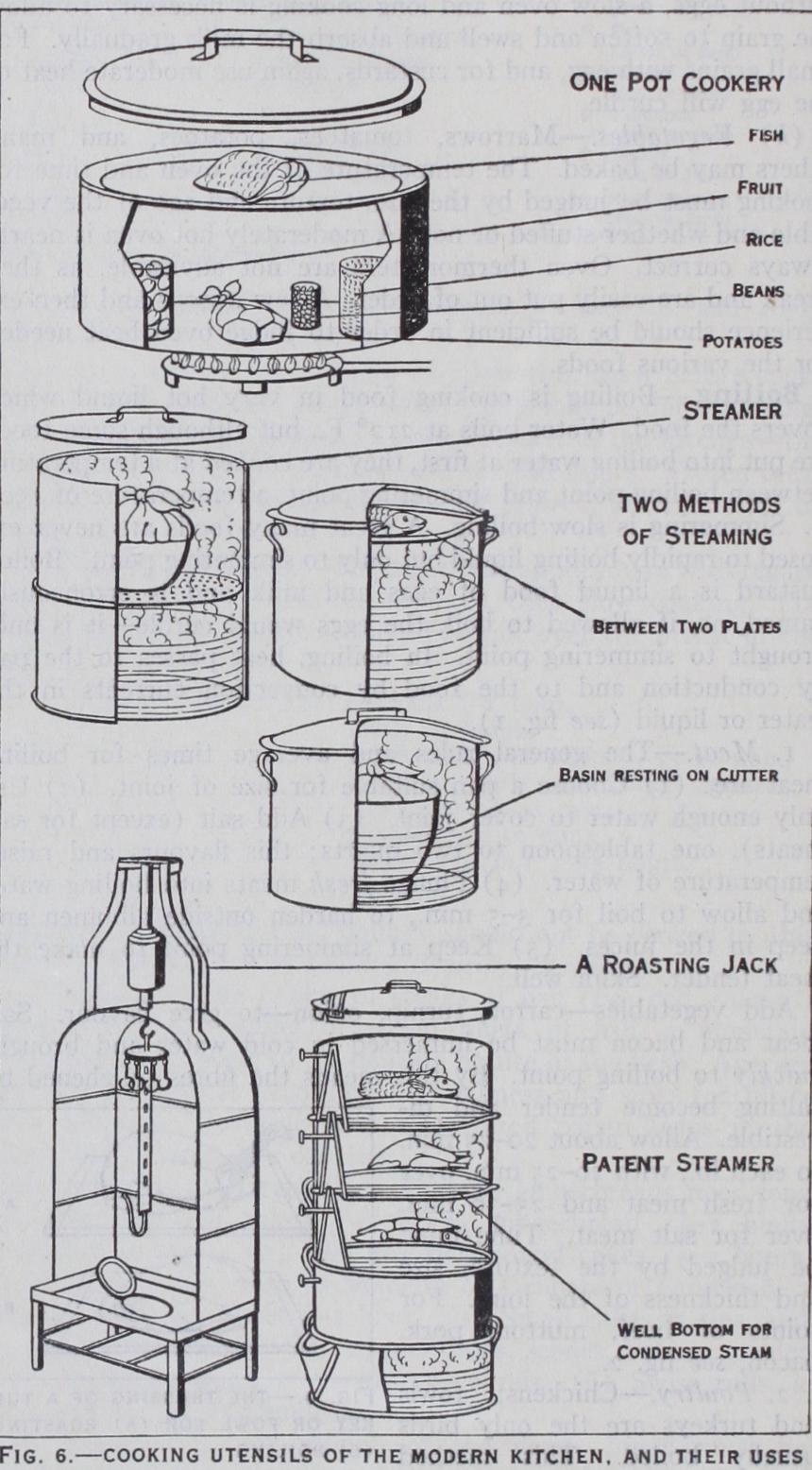

3. Fish.—Whole fish and thick slices or steaks of fish may be boiled, although steaming is more suitable in most cases. (See Steaming.) The general rules are : (I) Use a fish kettle (see fig. 6) if pos sible, or as a substitute put the fish in muslin with the ends corn ing just over the sides of the pan (see fig. 4). This makes it easy to remove the fish without breaking the delicate flesh. (2) The water must just cover the fish. (3) Add salt, one tablespoonful to two quarts, and for white fish one tablespoonful of vinegar or lemon juice to make the flesh firm and white. (4) Fresh fish must not be put into boiling water or the flesh will break, but into very hot water, which should simmer. Salmon, however, in order to keep its colour, may be plunged into boiling water. (5) Skim well.

Average Time.

Ten to 15 minutes to each lb. and the same over. Salt fish should be soaked, before boiling, for 12 hours. Mackerel and very oily fish should be put into tepid water to draw out some of the oil.4. Vegetables.—May be di vided into (a) roots and tubers: potatoes, artichokes, carrots, tur nips, onions, beetroot, leeks; (b) leaf and green vegetables: spinach, sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower; (c) stems: seakale, asparagus, celery; (d) seeds and seed cases: peas, beans, marrow, tomatoes. All these may be boiled and put in boiling water, except old potatoes (which cook more quickly if put into cold water, as they soften as boiling point is reached), and spinach, which boils in the water and juice from its own leaves; but boiling is not advocated, as the vitamin C (see VITAMINS) and valuable mineral salts are lost in the water. It is important to conserve the colour of green vegetables, and these may be par boiled or scalded in boiling water and then cooked by other methods (see Braising and Steaming).

General rules for boiling vegetables are : (I) Use boiling water with added salt (one tablespoon to one gallon), a little sugar for green vegetables, vinegar or lemon juice for white vegetables, both to keep the green and white colours. (2) Boil quickly, ex cept for cauliflowers. (3) Skim well. (4) Keep the lid on the pan except for greens. (5) Drain thoroughly. Average time: min.; beetroot and old carrots one hour or more. Age, size and texture must be considered.

5. Puddings.—Suet crust, fruit puddings, Christmas puddings and all puddings with flour and suet foundations may be boiled. General rules for boiling puddings are : (I) Plenty of boiling water to cover well the basin or tin. (2) Water must not go off the boil. (3) Pan must have a tightly fitting lid. (4) The mixture must fill the basin. (5) The basin must be covered with a floured cloth. Time:—At least II- hours and for most mixtures 2-3 hours or more.

6. Stocks, Soups and Sauces, being liquid, are classed under Boiling—they boil and simmer.

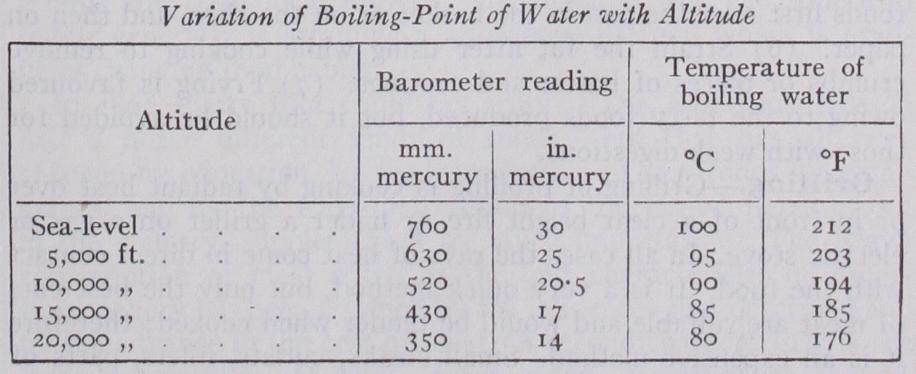

It must be remembered that at high altitudes the boiling point of water is appreciably lower than at sea level, and food takes longer to cook. The accompanying table gives the variation of boiling point with the barometer reading. The boiling temperature of pure water drops about I° C for every rise of i000 ft. above sea-level; the boiling point is slightly higher when salt is present in the water. In order to produce an artificially high boiling point a vessel with an airtight lid, called a "digester," may be used; in this the pressure (regulated by a valve) can be raised to any value that the vessel will allow.

Braising.

This is one of the best of all methods of cookery. It is used very little in England but a great deal on the Continent of Europe. It is a combination of the methods of stewing and baking, bottom and top heat being possible. True braising is carried out in a special braising pan (see fig. 5c). The construction of the lid prevents evaporation, the full flavour in the food is re tained and the baking and roasting process is accomplished by glowing charcoal being placed on the lid of the pan. In England a good substitute is made by cover ing the pan with greased paper which the lid keeps in place and which keeps in all flavours and moisture, and by placing the pan for the last one-third of cooking time in a moderately hot oven to obtain top heat instead of using glowing charcoal on the lid.Meat (small joints, sweet breads, kidneys, cutlets and fil lets), poultry, game, fish and vegetables may be braised. As lean meats are chosen they should be "larded" or "barded" (see barding and larding). A mirepoix of vegetables and bacon (see mirepoix) is prepared and the larded food to be braised is placed on this and cooked for two-thirds of the time over moder ate heat on the stove. The mirepoix is served and the stock re duced by boiling after the food and vegetables have been removed. This is a rich method of cooking but very palatable, and the food is tender and digestible.

Broiling: see

Grilling, below.

Frying.

Cooking foods in hot fat is known as frying.Method z.—Shallow or Dry Frying: (a) With sufficient fat to cover the bottom of the pan to prevent the food sticking to the pan. Suitable for cutlets, fillets, eggs, steaks, liver, omelets, pancakes, fish (slices, or fillets, or whole if small). (b) In a hot pan with no added fat, sufficient coming from the food fried; for bacon, oily fish, sausages. (c.) Sauteing, when food is tossed or sauted in the fat which is ultimately absorbed by the food; suitable for potatoes and other vegetables. Suitable fats for frying are: clarified fat, dripping, lard, margarine (usually too much water), butter (expensive).

Method 2.—Deep or French Frying: The food is immersed in a bath of hot fat in a strong iron pan, usually in a frying basket. If put straight into the fat a slice is used when removing it (see fig. 5b). Fats used as frying medium are oil (the best but too ex pensive) and clarified fat. Fat never boils when used for cooking— it is hot enough when it is still and a bluish vapour rises from it, the temperature being judged by the amount or density of the vapour.

Temperature varies from 32o°-400° F.; must be determined by the food, whether raw or cooked, whether of a delicate nature, whether large or thick, and so on: Fish from 34o° F., fritters from 32o° F., potatoes 400° F., meat 36o°-38o° F., whitebait 400° F. If over-heated, fat gives off a disagreeable smell. General rules for frying are : (r) The fat must be hot. (2) In shallow frying the food is turned; in French frying the fat must cover it. (3) In deep frying the food should be coated to prevent the fat becoming flavoured or penetrating the food. (4) Fry a few pieces at one time and allow fat to reheat between each fry. (5) Drain all fried foods first over the pan in the basket or on the slice, and then on paper. (6) Strain the fat after using while cooking to remove crumbs or pieces of batter and coatings. (7) Frying is favoured owing to the tasty foods produced, but it should be avoided for those with weak digestions.

Grilling.

Grilling or broiling is cooking by radiant heat over or in front of a clear bright fire or under a griller on a gas or electric stove. In all cases the rays of heat come in direct contact with the food. It is a very quick method, but only the best cuts of meat are suitable and would be tender when cooked; therefore it is an expensive method. Small steaks, cutlets, fillets, parts of poultry, sausages, kidneys, tomatoes, bacon, mushrooms and fish may be grilled. It is extravagant with regard to fuel if a coal fire is used, but the food is palatable and full of flavour. General rules for grilling are: (I) Have a clear bright fire, or the deflector on the stove red hot. (2) Great heat at first and throughout cook ing, but after the first five or ten minutes the food may be a little farther from the heat. (3) The gridiron is greased, also the food, to prevent it burning and sticking to the heated gridiron. (4) A cut surface should be first exposed to the heat. (5) The food should be turned constantly to ensure even cooking. (6) When finished, it should be tender and the juices retained in the centre. Average time: chop about 8-12 min.; cutlet about 8 min.; kidney about 8 min. or less; mackerel about 8-1 2 min.; steak about 12-20 min. according to thickness and taste.

Roasting.--This

is cooking by means of radiant heat in front of a clear bright fire. Heat, as in grilling, passes by radiation direct to the food, and is reflected by means of the roasting jack or Dutch oven (see fig. 6). In the jack the meat hangs and rotates and so is equally cooked on all sides; the Dutch oven is turned con stantly to ensure equal cooking. Suitable foods: meat, poultry and game. For rules, data as to time, and suitable joints see Baking. Roast meat has a finer flavour than baked owing to the free circulation of air round it. It is an expensive method because of fuel, the meat itself shrinks rather more, also the best cuts and joints are used. Modern ovens are so good and well ventilated that oven roasting has greatly superseded fire roasting.

Simmering.

See Boiling, p. 369.Steaming.—This is cooking by moist heat, viz., the steam from boiling water. Food either comes into actual contact with the steam as in the ordinary steamer, or the covered utensil in which it is cooked comes into actual contact with the steam. In this latter method the full flavour is retained in the food, whereas in the steamer some of the flavour must be drawn into the steam and boiling water. Steaming is one of the most useful methods of cooking, and the food is light, digestible and has a delicate flavour. It is suitable for children and invalids. Practically all foods may be steamed, and it is a method largely employed when re-heating.

Kinds of Steamers.—For the home a patent steamer, or an ordinary strong pan with a tightly fitting lid (see fig. 6). One pot cookery can be mentioned under this method (see fig. 6) ; for small institutions either the patent steamer or a self-filling steamer. For very large institutions cooking is done by super-heated steam and takes a very short time.

The conservative method of cooking vegetables is a method of steaming, whereby all the flavour and nutriment is conserved. The vegetables must be small or in small pieces; they are sauted in butter and allowed to cook slowly to absorb it, and they finish cooking in a little added stock, milk or water, sufficient only to be absorbed; the lid, which must fit tightly, is on the pan during both processes. Rules for steaming are : The water must boil rapidly and must be kept boiling. If it should evaporate, the pan must be filled with boiling water from a kettle. The lid of the steamer or pan must fit tightly to prevent any steam escaping. The food must be covered with greased paper to prevent con densation making the food sodden. The time for steaming is slightly longer than for boiling except in the case of super-heated steam, which is a very rapid method.

Stewing.—This is long, slow cooking in a small quantity of liquid in a tightly covered vessel either in an oven or over gentle heat. A stew should never boil but only simmer slowly. It is an economical method (I) because the cheap and tough meats, old and hard vegetables, old and tough poultry may be used, the long slow cooking making them tender, digestible and full of flavour, as all the nutriment and flavour are conserved ; salt fish and fish with coarse fibres are also best stewed ; (2) because very little fuel is needed; (3) labour is economized, as one pan cooks meat and vegetables, a stew is quickly prepared and, while cooking, needs little attention. For stewing in an oven use a casserole, a jar which must be covered, or a fireproof glass utensil with cover.

The Fireless Cooker or Haybox Cookery is a method of stewing, in which the food must be brought to boiling point, and when boiling the vessel must be packed into the box; the heat is thus conserved and the food continues cooking slowly. If fruit is stewed it is put into boiling syrup and then cooked slowly.

Classification of Meat and Poultry Stews.—(i) A clear stew: Stock or water are used without any thickening of flour, e.g., Irish stew, sea pie. (2) A brown stew for red meats and poultry. The gravy may be made first with a brown roux and stock or water (a roux is a blending of fat and flour) or the liquid may be flour before serving. (3) A white stew: White meat and poultry ; a sauce or gravy being made with a white roux, milk or white stock or water, or the thickening of flour may be added before the stew is dished. N.B.—Flour must boil 8–i o min. to cook it thoroughly. Very tough sinewy meat is softened by soak ing in vinegar before cooking. Flavour is developed in meat and poultry if fried lightly before stewing. (E. G. C.) It is only natural that in the United States of America cookery should be more cosmopolitan in character than in any other land, since the population is made up of more racial strains than any other. It is also natural that in so large an area, with so many different climates, there should be a great dissimilarity in different regions both in food materials and in methods of preparing them. However, the fact that climates from the north temperate to the tropical are included within the borders of the country has acted also to equalize markets by the distribution of the foods of any part of the country to the other parts desiring them. The canning industry also makes available everywhere meat, poultry, fish, vegetables and fruit in endless variety. The American food mar kets to-day present a variety to be found in no other country. This fact has already modified local practices and is bound to modify them further. The production of food by the individual consumer has lessened as the food industries have grown, and the latter are now largely regulated by legislative acts, to protect the purity of the product.

The early settlers had a very limited range of food materials. They adopted at once the maize, or Indian corn—known now simply as "corn" in the United States. They depended for meat chiefly on game, which was abundant, and soon added the wild turkey to the food birds known to them before. Fish and shell fish were also plentiful as all the settlers were on or near the Atlantic coast. Curiously, the salmon and the shad, abundant in those days, were commonly disregarded, although now much valued. Cod, mackerel, oysters and lobsters were then, and have remained, important foods, although the lobster is now compara tively scarce, and the oyster of the Pacific coast differs much from that of the Atlantic coast. Corn meal is still largely used, espe cially in the South, which prefers the white meal, while the North generally uses the yellow. The South soon added rice. From the Indians the settlers learned of not only corn, but the pumpkin and succotash—a dish of corn and beans. Baked beans was a staple dish. Preserving fruit required much sugar, since they had no containers that could be sealed. Since the settlers had few vegetables, even the white potato being rare in the early days, they added much meat to their corn meal dishes, and this per haps began what is the present American practice of consuming more meat per person than the people of any other country. (The slaughtering and packing of meat is still the largest manufactur ing industry of the United States.) This may be considered the first characteristic of American cookery—the abundance of meat. Broiling or grilling has always been the best method of cooking tender meat, and the beefsteak of the United States, thick, juicy and tender, is one of its outstanding dishes. In default of proper broilers in the early days, such meats were pan-broiled—"fried" is the common term—and when this was badly done, with too much fat, it helped to produce the indigestion for which the inhabitants were at one time famous. As there was no way of keeping fresh-killed meat when it could not be frozen, smoking, corning and later "jerking" (drying) were common. The pig, the food animal easiest raised, soon furnished much of their meat, ham, bacon and salt pork being staples.

The teaching of cookery and nutrition commenced in the United States, about 187o. This has become general in public schools as well as in higher schools, and has been supplemented by printed education. Women's magazines are constantly giving the house wife information about methods of cookery and the value of foods. Many newspapers do the same. Further, the advertising of food products has been of great educational value. Some misinformation has doubtless been given, but the standard is gen erally high with the large food firms, and many publications em ploy home economics experts to make the information they give, both as to methods of cookery and food values, of unquestioned authority. In addition, the U.S. bureau of home economics has done experimental work and issued practical food bulletins, liter ally in millions. Most States have "extension" departments on the subject, spreading their information not only in print, but by the work of trained women going through the State to address groups and train local leaders. The result is that the American public generally is attaining a knowledge of food which is grad ually changing food habits.

In 1867 Pierre Blot could say truly: "The Americans live on half a dozen different kinds of foods," but that has all been changed by education, by the introduction of new foods by immi grants, and by the wide distribution of the varied foods grown in the country, supplemented by much importation. The heavy consumption of meat noted as the first characteristic of Amer ican cookery has been lessened by the influences just described and by the advance in the cost of meat. A second characteristic is the large consumption of fruit—fresh, dried, preserved or canned.

There are few American families where fruit is not served at one meal every day, and in many it is part of all three meals. Fresh fruit is served uncooked, stewed, baked, broiled, pan-fried or made into a dessert with other materials. A third characteristic is the wide use of salads and green vegetables. Green salad materials are now available to almost everyone the year round, and these are served as an extra course or with the main dish. Green vegetables are increasingly marketed all the year, and where these are not available fresh, the canned vegetables may be obtained. Methods of cooking vegetables are varied. A popular cook-book gives recipes for 25 ways of cooking potatoes. A fourth characteristic is the general use of breakfast cereals. The corn meal mush, oatmeal and rice used early in the history of the country have been sup plemented by dozens of manufactured products, some partly cooked, some ready to eat. Increasing numbers breakfast on fruit, cereal and a cup of coffee. The heavy breakfast of early days, with meat, potatoes, griddle cakes and doughnuts or pie, is rarely found now except in the families of those doing manual work. A fifth characteristic is the great variety of desserts (in Britain called sweets). The general use of pie began early and continues. The word means a dessert, with a lower crust and perhaps an upper crust of pastry, the filling usually of fruit. This and ice cream are used everywhere, and the two are even served together, the ice cream on the pie. Many other frozen desserts besides ice cream are common, and the growing use of the elec tric or gas refrigerator will presumably increase their number. Cake is made in bewildering variety, although it is no longer the pride of the housewife, as it was earlier, to serve six kinds at one meal. Bread is served with every meal in most homes. Much is still made in the home, but the growth of the baking industry has been rapid, and even in remote country districts "baker's bread" has in many families replaced the home-made product. Small breads, especially if to be served hot, are still commonly made at home, although those made by the bakers are growing in number and variety. The word "bread" in the United States usually means bread of milled wheat flour—white bread—but whole wheat bread and rye bread are much eaten. Yeast, a home-made produc tion in early days, is now rarely so made, manufactured yeast being marketed everywhere in a standardized and easily usable form. Commercial baking powders have almost entirely replaced the "soda and saleratus" (cream of tartar) of older times. The salt-rising bread still popular in some parts of the country is a "wild yeast" bread made in the home. Crackers (biscuits) are manufactured and imported in great variety, one of them—pilot bread—being a reminder of the influence of sea cookery. Coffee, tea and cocoa (chocolate) are all in general use, the first being the favourite American beverage. "Soft drinks" have always been popular and since the prohibition of alcoholic beverages their use has grown greatly. Many of these drinks, such as fruit punches, are commonly made in the home. The amount of milk used increases steadily, and this rather as a beverage than for use in cookery. The national slogan of "A quart a day for every child" has had great effect. Condensed, evaporated and dried milk supplement the supply of fresh milk. The sugar consump tion of the country for domestic use is very high, and, in addition, enormous amounts of candy are manufactured, bewildering in variety and ranging from simple sweets to the richest and most complicated. The early settlers depended for sugar largely on honey and maple sugar, and the special flavour of each is still much prized, but the amount produced is small compared to that of cane and beet sugar. At first cheese was made at home, but the making of all except cottage cheese began to cease in the home (1851) and now a home-made cheese is a rarity. Cottage cheese is marketed, but also very generally made at home, even in cities. Cheese dishes are much used as "meat substitutes." Seasonings were few in colonial times, but the sea trade with the West Indies and the Orient soon increased the number. The importance of season ings in the art of cookery is not yet as fully recognized as in France, but is being more and more studied. Sauces are said to be the test of a nation's cookery. The United States has devel oped none of any importance, but has taken from many nations numerous varieties, and uses them increasingly with intelligence.

Methods of cookery have changed with conditions. A primitive method was to build a fire on stones to heat them, rake off the ashes and coals, lay the food on the stones, and cover it to steam. Another was to roast food in the hot ashes. Both of these survive in the New England clam bake, for which the clams on the hot stones are covered with wet seaweed, then with canvas, and also in the corn roast or potato roast. Hunters still cook birds by coat ing them, feathers and all, with clay, and roasting in hot ashes. The name if not the method survives in the hoe-cake or ash-cake of the South, originally cooked in the fields by the negroes on a hoe blade thrust into the ashes. The early settlers had only the open fire and the brick oven. The first cooking stoves were mar keted about 183o, and later came the gas range, the oil stove, the fireless cooker (q.v.), the electric range and electric appliances for table cookery (see HOUSEHOLD APPLIANCES). Broiling became much easier with the gas and electric range, and so more general. Roasting, done on a spit before the open fire, was transferred to the oven and became really baking. Planking is usually broiling, though sometimes baking—the meat, fish or poultry being cooked on a stout plank, prepared for the purpose, and on it taken to the table. Braising, uncommon in earlier times, increased when stoves came in, and with the arrival of races using this method. Steam ing has increased steadily, and many types of steamers are now marketed. This method of cookery has been urged because it retains the valuable salts and juices. The steam pressure cooker has been in use for some time for canning and also for cooking quickly at a high pressure of steam. Waterless cookery now has many advocates, a method by which meat, poultry, fish, vegetables and fruit are cooked in their own juices, in utensils allowing this without danger of burning. Paper bag cookery had a brief vogue, but is not now much in use. Chafing dish cookery is fairly com mon, the electric chafing dish having in many instances replaced that with an alcohol or spirit lamp. Kitchenette cookery means only recipes and directions for dishes easily prepared with the limited resources of the kitchenette. Special methods for cookery in high altitudes have been developed.

The use of the thermometer in cookery, insuring the exact de gree of heat needed, is growing. Special thermometers are used for deep fat frying and sugar cookery, oven thermometers for baking. Many cooking ranges are now made with an oven ther mometer attachment and some with a thermostat for regulating the heat.

New England still eats baked beans, clam chowder, corn bread, Boston brown bread, salt fish and pie of all kinds—but most of these are favourite dishes everywhere. The North Atlantic States still enjoy the crullers and doughnuts brought by the Dutch—but so do most Americans. Pennsylvania "Dutch" cookery is more nearly confined to its own area. The South still eats hot breads in great variety for breakfast, and beaten biscuit strays rarely from there. They use much rice, white corn meal in many forms, gumbos, Brunswick stew, Lady Baltimore cake—but all these are also enjoyed elsewhere. In New Orleans creole cookery still pre vails, and some of the dishes are used in the North and West. The Middle West has taken from its inhabitants of Scandinavian and German origin many of their dishes, to add to those brought from the East and the South. The South-west has added to its menu many Mexican dishes—tamales, tortillas, Mexican beans and dishes with some one of the many chili peppers. The Far West has also adopted Mexican- dishes, and is perhaps the most cos mopolitan of all in its general home cookery. Everywhere one finds beefsteak, ham and eggs, corned-beef hash, baked beans, griddle cakes (under different names), salads, pie and ice cream.

(I. E. L.)