Orbits of Comets

ORBITS OF COMETS Law of Gravitation Applied to Comets.—It was impossible to ascertain the true orbits of comets till the law of gravitation had been established. Newton proved that under a force that diminished in proportion to the inverse square of the distance, a body could describe any of the curves known as "conic sec tions," that is, the circle, ellipse, parabola or hyperbola. It was soon recognized that the observed movements of comets could be explained on the hypothesis that they were travelling round the sun in elongated ellipses or in parabolas, being visible for only a small portion of their orbits in the neighbourhood of the sun. Newton himself applied the new principle to the brilliant comet of 168o; subsequently he obtained the assistance of Halley, who in '704 collected the observations of 24 comets, commencing with that of the year 1337, and calculated their orbits; he made the preliminary assumption that they were moving in parabolas, since this simplified the work. All parabolas are of the same shape, so that tables can be constructed that are available for all cases; the same assumption is still made in calculating the orbits of new comets, since it is known to be true in the majority of cases.

On collecting the orbits thus found, Halley noticed that there were three, thcse of 1531, 1607 and 1682, that were moving in paths that were practically identical. The intervals between their appearances were not exactly equal, the first being longer by 15 months ; but Halley saw that this could be readily explained by the disturbing action of the large planets, Jupiter and Saturn; in the case of elongated orbits a small change of velocity has an exag gerated effect on the period. Examination then revealed records of another appearance of the same comet in 1456. It was confi dently and correctly assumed that all four apparitions belonged to a single body, whose return might be expected about 1758. The fact of a comet's return was now established for the first time. There had been some conjectured cases earlier; but they were erroneous, the orbits not having been deduced on correct prin ciples. Halley's prediction was justified by the result, the comet having returned in 1759 and again in 1835 and 1910.

Comets of Short Period.—Halley called his comet a "Mercury among comets," supposing that it had the shortest period of any; this has been known to be incorrect since the discovery of Encke's comet early in the 19th century. This is the true "Mercury of comets," its period being three and one-third years. More than 6o other comets are known whose periods are less than 8o years. These divide themselves naturally into four groups, to which are given the names of the four giant planets. There is not much doubt that there is some connection between each group and the planet whose name it bears. Jupiter's family is much the largest, containing some 5o members, whose periods lie between 3.3 and 8.9 years; the mean is 6.38 years, which is 0.538 of Jupiter's period ; the orbits of most of the members pass close to that of Jupiter. Saturn's family has four members; their periods lie between 13.1 and 17.7 years; the mean is 14.9 years or 0-57 of Saturn's period. Uranus has only two comets; the mean period is 36.6 years, or 0.44 of Uranus's. Neptune has the considerable family of nine comets, including that of Halley; their mean period is 70.9 years, or 0.43 of Neptune's. The connection of the first family with Jupiter is not disputed; his influence on many of its members has been considerable. But the connection of the other planets with their families is not universally recognized. There seems to be a good case for assuming connection; the divisions between the families are well marked, and the mean period of each family is about half that of its planet ; this implies that their aphelia (the points of their orbits furthest from the sun) are near the orbits of their respective planets; no other comets are known with periods of less than 120 years, except those in the four families. The nature of the connection between the planets and their families will be discussed in the section "Origin of Comets." Our knowledge of the short-period comets may be said to date from 1819. There were a few cases before that when a parabolic orbit was found not to satisfy the observations, and an elliptical one was deduced. The following is a list of them: Lahire's comet 1678, period 5.38 years; Grischow's comet 1743 I., 6.73 years; Helfenzrieder's comet 1766 II., 4.5 years; Messier's comet 1770 I. (now known as Lexell's comet), 5.6 years; Mon taigne's comet 1774 (now known as Biela's comet), 6.77 years; Pigott's comet years. In many of these cases the ob servations were rough, and the period considered doubtful; it had not been verified by the return of the comet. We now know that Biela's comet was seen again in 1806, 1826, etc., but this had not then been recognized.

Encke's Comet.—On Nov. 26, 1818, Pons, an assiduous comet hunter at Marseilles, found a telescopic comet that was observed for 4o days; J. F. Encke, a celebrated German astronomer, under took the study of its orbit, and found that it was an ellipse with a period of 3.3 years, which was then, and still remains, the shortest known cometary period. Encke was able to prove, by laborious calculation of the disturbances produced by Jupiter, that comets seen in 1786, 1795 and 1805 were identical with it; he predicted the circumstances of its return in 1822, which were exactly verified. From that day to the present time, the comet (which bears Encke's name, owing to his brilliant work upon it) has been observed at every return. There is only one other comet that has a similar unbroken record, namely Halley's comet. The reason in the case of Encke's comet is that it passes within 31 mil lion miles of the sun, which is much closer than the other comets of short period ; it is then so brightly lit up that it is usually an easy object to observe. It has also been fortunate in having a succession of able mathematicians, Encke, von Asten and Back lund, to calculate the disturbances in its orbit. One peculiarity noticed by Encke was that, after making allowance for planetary disturbances, the period was getting shorter by two and one-half hours each revolution. It was conjectured that this might arise from a "resisting medium" in space, which slightly retarded the comet's motion; it can be shown that such a retardation brings the comet nearer the sun and shortens its period. Against this suggestion is the fact that other short-period comets do not show the effect ; but it can be replied that Encke's comet passes nearer to the sun than they do, and the medium would probably be denser there. A more serious objection is that the effect has gradually diminished in amount; it lost 20% in 1858, another 20 in 1868, 28% in 1895, and there was a further loss about 1905, bringing the amount dowrf to one-ninth of what it was before 1858.

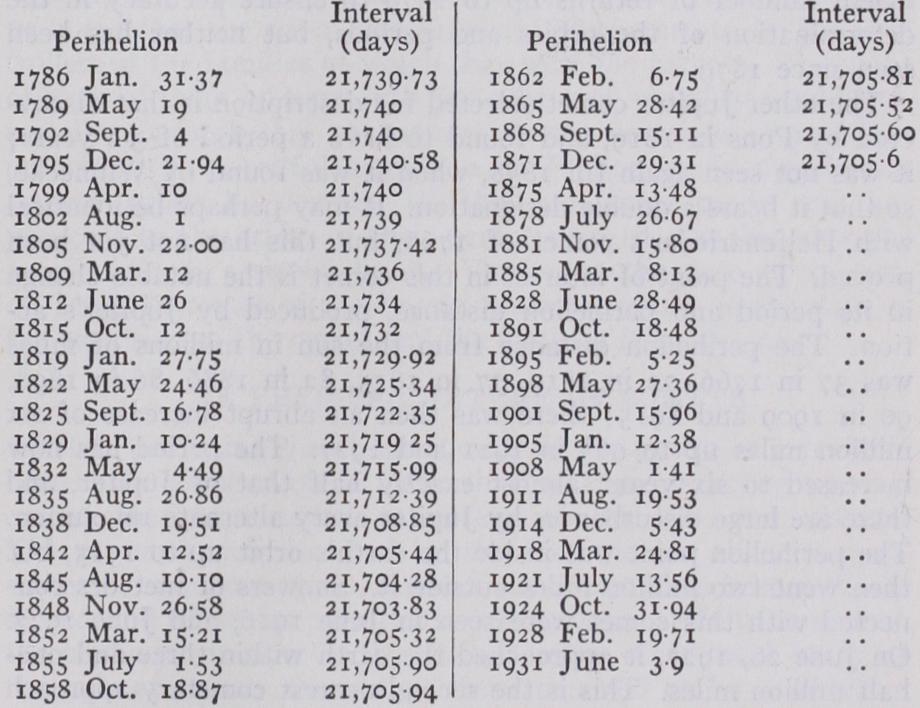

It is worth while to exhibit the changes in the period by giving a table of the dates of perihelion passage (that is, the time when the comet is nearest to the sun). These are given in Greenwich civil time; after each perihelion up to 1871 is given the interval in days to the 18th following perihelion, about 592 years later (equal to five revolutions of Jupiter and two of Saturn, so that their disturbing action nearly repeats itself after the interval) . It will be seen that the interval suffers a rapid diminution at one part of the table, but remains almost stationary towards the end of it ; it is easy, with the aid of this table to predict future returns within less than a day.

Encke's comet is generally easier to see before perihelion than after it ; the approach to the sun causes its envelopes to expand till they become very diffused and faint. This comet makes occasional close approaches to Mercury, whose perturbations of its motion afford the best determination of Mercury's mass; Back lund deduced the value of one nine-millionth of the sun or one twenty-seventh of the earth, a smaller value than that previously adopted.

Other Comets of Jupiter.

The aphelion point of the orbit of Encke's comet lies 84 million miles inside Jupiter's orbit. The other members of Jupiter's comet family make much closer ap proaches to it, occasionally penetrating within its satellite sys tem. The smallness of cometary masses is demonstrated by the absence of any disturbance to the motion of the satellites, whereas the comet's orbit suffers great changes. The orbit of Lexell's comet of 177o underwent such changes both in 1767 and that its previous and subsequent paths were outside our sphere of vision. Other comets that have undergone large disturbances from Jupiter are d'Arrest's in 1860, Brooks's in 1886, Wolf's in 1875 and 1922 ; curiously enough, in this latter comet the second perturbations almost exactly reversed the first, and sent the comet back to its former path.Space forbids a full account of all the members of the Jupiter family; two of the more interesting members are selected as spec imens. The first is Biela's comet; this was seen in 1772 and 1805, but its orbit was not definitely fixed till Biela and Gam bart found it independently in 1826. Its period was found to be six and three-fourths years, and its orbit intersected that of the earth, a fact which caused much groundless alarm at its return in 183 2 ; this, however, was the occasion of a useful popular bro chure on this comet, and comets in general, by the famous Arago. The return of the comet in 1839 was not seen, the comet being badly placed. In 1846 the surprising discovery was made that it had split into two comets, which travelled side by side at a nearly constant distance. The division of a comet into two equal portions is a very rare occurrence, though several cases of the separation of small fragments are known; it has, however, been conjectured that the family of brilliant sun-grazing comets that appeared in 1843, 188o, 1882, 1887, were separated portions of a single comet. The two portions of Bielft.'s comet appeared again in 1852, somewhat further apart. Their non-appearance in 1359 excited no surprise, since they were badly placed in the sky; but early in 1866 their calculated position was favourable, yet in spite of careful search nothing could be found ; nor have they ever again been seen as comets. Their presence has been mani fested in the shape of showers of meteors; displays of these, mov ing in the same path as the comet, occurred on Nov. 27, 1872, and again in Nov. 1885, 1892 and 1898.

The disappearance of Biela's comet is evidence of the transitory nature of short-period comets. Two other comets, Brorsen and Tempel I., have likewise been lost ; both were observed at a suf ficient number of returns up to 1879 to ensure accuracy in the determination of the orbits and periods, but neither has been seen since 1879.

The other Jupiter comet selected for description is that discov ered by Pons in 1819, and found to have a period of 5.6 years; it was not seen again till 1858, when it was found by Winnecke, so that it bears a double designation. It may perhaps be identical with Helfenzrieder's comet of 1766, but this has not yet been proved. The point of interest in this comet is the notable change in its period and perihelion distance, produced by Jupiter's ac tion. The perihelion distance from the sun in millions of miles was 37 in 1766, 72 in 77 in 1875, 82 in 1886, 86 in 1898, 90 in 1909 and 1915; there was then an abrupt increase of six million miles up to 961 in 1921 and 1927. The period has now increased to six years, almost exactly half that of Jupiter, and there are large disturbances by Jupiter every alternate revolution. The perihelion point was inside the earth's orbit up to 1915, but then went two million miles outside it. Showers of meteors con nected with this comet were seen in June 1916, and June 1927. On June 26, 1927, it approached the earth within three and one half million miles. This is the second nearest cometary approach on record ; the nearest is that of Lexell's comet in 17 7o within one and one-half million miles. The comet Pons-Winnecke was clearly visible to the naked eye in 1927, and its nucleus appeared like a small star; its diameter was not greater than some two miles.

Comets of Saturn and Uranus.

The best known member of Saturn's family is Tuttle's comet, discovered in 1858, and then found to be identical with Mechain's comet of 1790. Its period is 131 years, and it has been seen at every return since 1858.The more interesting of Uranus's two comets is Tempel's comet, found in 1866. Its period is one-third of a century, and its orbit coincides with that of the "Leonid" meteors, which are seen in November to radiate from the "sickle" of Leo. There were bril liant displays of these in 1833 and 1866, but that of 1899 was much poorer, since perturbations by Jupiter had diverted their course away from the earth. This comet is the first (following the order of increasing period) whose motion is retrograde, or opposed to that of the planets. It has not been seen at any other return, unless it be identical with one seen in China in 1366; if identical, it has greatly diminished in splendour; it was a con spicuous naked-eye object in 1366, but a feeble telescopic one in 1866. Le Verrier has made researches on the previous history of this comet, and concluded that it made a close approach to Uranus in A.D. 126. At present their orbits are separated by 35 million miles. The comet was not seen in 1899. Stephan's comet of 1867 is the other member of the Uranus family; this also has not been observed again.

Neptune's

Comets.—Neptune's family is much larger and bet ter observed than that of Uranus. It has nine members, of which five have been observed at a second apparition. Halley's comet heads the list; this has been traced back to 240 B.C. by comput ing the planetary perturbations. At every return except that of 163 B.C. it has been identified with an actually observed comet. There is a possible identification in 467 B.C. ; both the Chinese an nals and Aristotle (in Meteorologica) record this comet : the latter adds that a large meteor fell (at Aegos Potami) while the comet was visible; this increases the probability that it was Halley's comet, since it is one of those that approach near enough to the earth to give meteor showers. The apparition of this comet in A.D. io65 is recorded on the Bayeux tapestry. The head of the comet passed across the sun in 1910, but was absolutely invis ible, demonstrating the very small amount of matter contained in it. The earth probably passed through the tail at that time; but there was little, if any, evidence of its presence. There was a sim ilar passage of the earth through the tail of the great comet of 1861; no phenomenon was noticeable beyond a diffused glare, demonstrating the very small density of the tails of comets. Four other members of Neptune's family have been seen on their sec ond visit; these are (1) Pons-Brooks, 1812 and 1884; (2) Olbers, 1815 and 1887; (3) Westphal, 1852 and 1913; (4) Brorsen Metcalf, 1847 and 1919. These are inferior to Halley's comet in brightness, but superior to most of the Jupiter comets. Three of the Neptune family have retrograde motion; these are Halley's comet, the Pons-Gambart comet 1827 II., and Ross's comet 1883 II.The influence of Neptune on his comet family in the present position of their orbits is very small. The least distances between the orbits of Neptune and the different comets are given in terms of the distance from the earth to the sun:—for de Vico's comet it is four units; for the comets Pons-Brooks and Pons-Gambart six units; for Halley's and the Brorsen-Metcalf comet eight units; for the comet 1921 I. (Dubiago) it is ten units; for the other three comets, Olbers, Westphal and Ross, it is about 18 units. It must, however, be remembered that the influence at a given dis tance increases as we go further from the sun, since the solar in fluence is very small in those outer regions. Thus Neptune is never less than ten units from Uranus, yet it disturbs it noticeably. It is probable that disturbances by Jupiter have gradually changed the orbits of these Neptune comets, and that they once came much closer to Neptune.

It is possible to trace evidence of comet families still further from the sun. There are no comets known with periods between about 8o and 120 years; then we have the following group of four comets: (I) 1862 III. (Tuttle), period 119 years; this is the comet associated with the August meteors; (2) Barnard's comet, 1889 III., period 128.3 years; (3) Mellish's comet, 1917 I., period 145-0 years; (4) the comet Grigg-Mellish, 1907 II., identified by E. Weiss with that of 1742, the period being there fore 164.3 years. This last is the only comet outside the Nep tune family that has been observed at a second return. There is a possible fifth member of the family; the comets of 1532 and 1661 have such similar orbits, that identity is suspected; if so, the period is 128.3 years. This family gives some ground for sus pecting the existence of an extra-Neptunian planet with period about 335 years and distance 48.2 units. It is noteworthy that both Lowell and Gaillot deduced the existence of a planet at about this distance from small unexplained perturbations of Uranus. There is some evidence for another comet family with periods near 40o years, which would give 1,000 years for the associated planet. Prof. G. Forbes strongly supports the existence of this planet from cometary statistics, but it is far more doubtful than the 335-year one.

Comets of Long Period.—We pass on to the comets whose orbits are scarcely distinguishable from parabolas. There has been considerable controversy as to whether these are to be regarded as true members of the solar system or stray wanderers from out side it. The matter is, however, capable of being settled by simple considerations. The relative motions of the stars, includ ing the sun, are of the order of several miles per second; a comet entering the sun's sphere of influence with such a speed would travel not in a parabola, but in a strongly marked hyperbola. No comets have been observed to travel in such orbits, and it is safe to conclude that they do not come to the solar system from outside. The suggestion has been made that the number of comets in interstellar space is very large, and that we see only those exceptional ones that happen to enter the sun's sphere of influ ence with zero relative velocity, all others passing too far from the sun for us to see them. This suggestion rests on a fallacy. The number of comets with no thwart velocity, but with velocity in the line between them and the sun, would be far greater than the number with zero velocity in both directions ; the former would pass through our sphere of vision equally with the latter, and their orbits would be of the markedly hyperbolic form that has never been observed.

This conclusion is strengthened by another consideration. If comets came to the solar system from outside, we should meet more coming from the direction towards which the solar system is moving (not far from the bright star Vega) than from the opposite direction. Now on tabulating all the comets that have appeared since 1700, and excluding those with periods less than i,000 years (since their orbits have probably been modified by planetary perturbations), it appears that, up to the year 1862, 63 comets came from the hemisphere containing the solar apex, and 76 from the opposite one. Between 1862 and 1927 the num bers are 61 and 96 for the two hemispheres. It should be noted that comets coming from the anti-apex hemisphere are some what better placed for northern observers than those from the apex one; but this consideration should have less weight in the more recent period, in which there have been several careful comet-observers in the southern hemisphere. The figures show that there is certainly no excess of comets from the apex hemi sphere, and therefore that they do not come from outside the system.

Origin of Comets.—On examining the comets of long period that have appeared since i 700, we find that 139 had direct motion (that is, in the same direction as the planets) and 157 had retro grade motion; there is thus no preference for direct motion in these comets. This makes it very difficult to form any theory to explain their origin; if they date back to the same epoch as the formation of the family of planets, we should expect that the di rection of motion which is so strongly favoured in the one case (there are no exceptions among the planets, but there are a few among the satellites) should prevail in the other likewise. But the statistics show that the preference is slightly in the other direction. It must be admitted that there is no satisfactory theory of the origin of the comets of long period. We may postulate a solar origin for the family of sun grazing comets that appeared in 188o, 1882, 1887. The phenomena of solar prominences indicate that matter is frequently being driven off from the sun at high speed. If the speed of ejection is less than 383 miles per second (the speed for motion in a parabola) such matter will return to the sun; but planetary perturbations may suffice to cause it to miss the solar surface and continue to circulate round it in a long ellipse. It seems, however, scarcely possible to postulate a solar origin for the numerous comets whose paths do not approach the sun within a distance of ioo million miles; and we must leave the question of their origin as one to which we cannot at present return an answer.

A suggestion is, however, possible in the case of the short period comets. The explanation generally adopted is that they were formerly long-period comets that happened to pass very near to one of the giant planets, and suffered large perturbations, which reduced their periods to their present value. It is easy to calcu late that only a few comets would pass close enough to Jupiter in a million years to suffer such a great change in their orbits.

This does not appear to be at all adequate to keep up the sup ply, in view of the rapid wastage that is going on. In the last century we have witnessed the definite disintegration of Biela's comet, while those of Brorsen and Tempel I. have probably suffered a like fate. An alternative theory was suggested by R. A. Proctor about 1870. He suggested that the comets in ques tion had been expelled from the planets to whose families they belong at a time when these planets were still in a semi-sunlike state. This involves the conclusion that these comets have been travelling in their present orbits for millions of years; it is dif ficult to accept this, but it does not seem to be impossible that the giant planets may still be in a condition to expel comets. The radiometric researches of Lampland, Coblentz and others have proved that their outer cloud-layers are cold ; but since their cloud-mantles are thousands of miles thick, this is not incon sistent with a state of great activity (perhaps of a volcanic char acter) lower down. In fact many of the disturbances seen in their atmospheres, such as the great red spot on Jupiter and the bright spots on Saturn in 1876 and 1903, are proofs of the existence of sources of energy at a great depth in their atmospheres, where solar energy could not penetrate. There does not appear to be any impossibility in the hypothesis that occasional discharges of torrents of matter may take place at speeds sufficient to carry the matter away from the planet. The necessary speed in miles per second is 371 for Jupiter, 224 for Saturn, 131 for Uranus, 13 4 for Neptune. Such speeds may appear improbable, but the capture theory involves much greater improbabilities. The ex pulsion theory gives a possible explanation of the non-occurrence of retrograde orbits in the Jupiter family, while we meet them in the Uranus and Neptune families. The speed of expulsion nec essary for retrograde motion would be 5o miles per second from Jupiter, but only a third of this for the outer planets. It may be noted that the outer planets would soon cease to be the con trollers of the families of which they were the parents. The paths of such of them as came into our sphere of visibility would nec essarily approach that of Jupiter; on the occasions of such ap proaches, the powerful attraction of Jupiter would modify the comets' orbits by degrees, till they no longer made near ap proaches to the orbits of their parent planets. On this view the year A.D. I 26, assigned by Le Verrier as the date of capture of Tempel's comet of the Leonid meteors, would be the date of the expulsion of the comet and the meteors from Uranus.