Output and Manufacture Copper

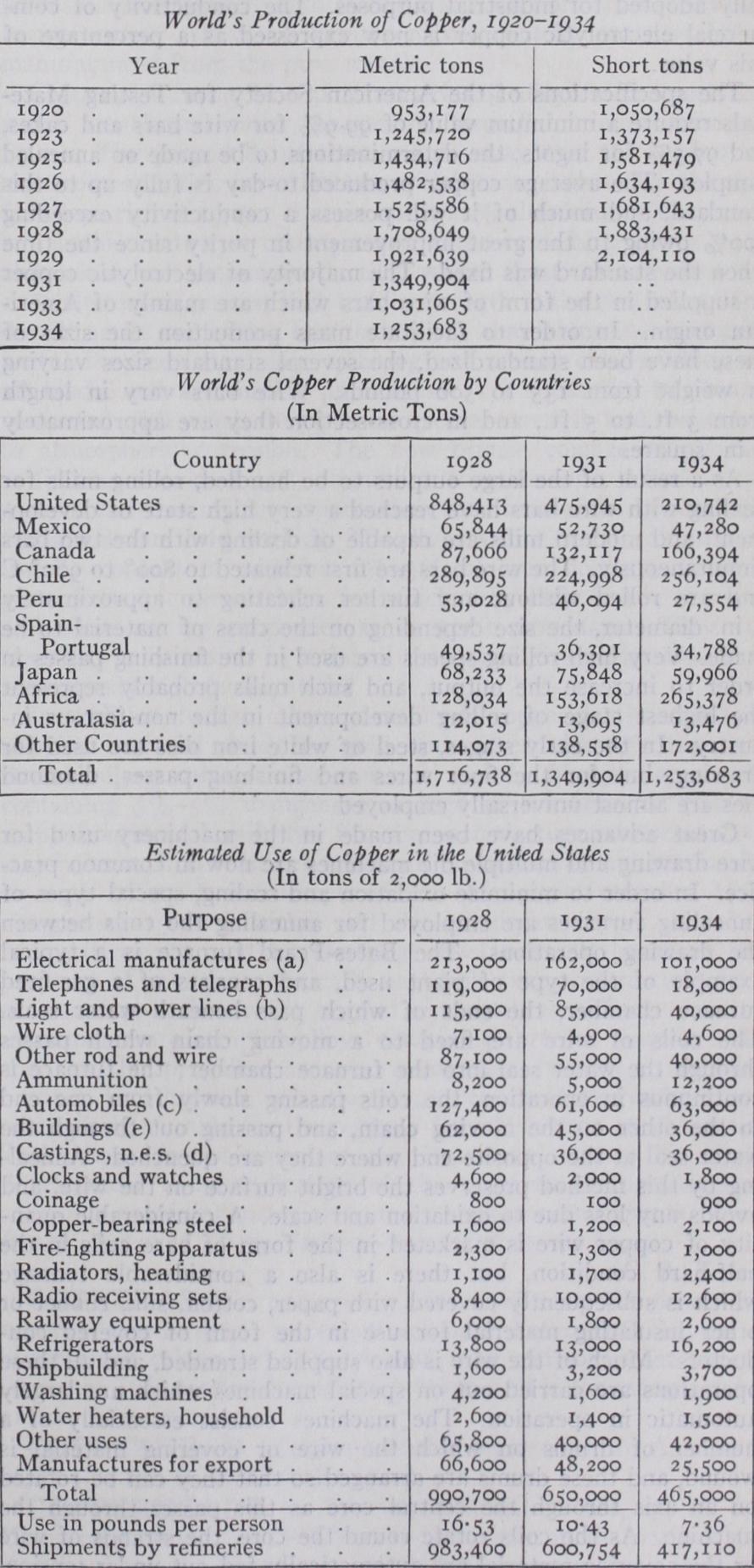

COPPER, OUTPUT AND MANUFACTURE. Before the World War, the world's production of copper had risen to about i,000,000 tons per annum. From 1916-18 this rose to ap proximately 1,400,00o tons. For the next few years, owing to trade depression, production was restricted, but in 1926 the pro duction exceeded the war-time maximum with 1,469,463 tons. Important new sources of the metal are being developed in Chili, Peru, Africa and Canada.

(a) Generators, motors, electric locomotives, switchboards, light bulbs, etc. (b) Transmission and distribution wire and bus bars. (c) Does not include starter, generator, and ignition equipment. (d) Bearings, bush ings, lubricators, valves and fittings. (e) Excludes electrical work.

Copper in the Electrical Trade.

The major portion of the I world's production of copper is utilized by the electrical industries, and of the remainder the greater part is finally used mixed with other metals in the form of alloys. This leaves a comparatively small portion of the total production to be absorbed for general purposes. The table on page 407 gives an approximate analysis of the consumption of copper in the United States and the purposes for which it was utilized.

Standard Electrolytic Copper.

Typical samples of electro lytic copper will contain from to copper, and of the remainder the major portion will consist of oxygen. A metal of this purity will show a conductivity of 99.8% to t oo.3 % as compared with the International Annealed Copper standard of 5,328 ohms at 2o° C, this system of measurement being univer sally adopted for industrial purposes. The conductivity of com mercial electrolytic copper is now expressed as a percentage of this value.The specifications of the American Society for Testing Mate rials require a minimum value of 99.9% for wire bars and cakes, and 97.5% for ingots, the determinations to be made on annealed samples. The average copper produced to-day is fully up to this standard, and much of it will possess a conductivity exceeding i00% owing to the great improvement in purity since the time when the standard was fixed. The majority of electrolytic copper is supplied in the form of wire bars which are mainly of Ameri can origin. In order to facilitate mass production the sizes of these have been standardized, the several standard sizes varying in weight from 135 to 50o pounds. Wire bars vary in length from 3 ft. to 5 ft., and in cross-section they are approximately 4 in. square.

As a result of the large outputs to be handled, rolling mills for dealing with wire bars have reached a very high state of develop ment, and modern mills are capable of dealing with the two bars simultaneously. The wire bars are first reheated to 800° to 900° C and are rolled without any further reheating to approximately in. diameter, the size depending on the class of material to be made. Very high rolling speeds are used in the finishing passes in order to increase the output, and such mills probably represent the highest stage of rolling development in the non-ferrous in dustry. In the early stages, steel or white iron dies are used for drawing, but for the finer wires and finishing passes, diamond dies are almost universally employed.

Great advances have been made in the machinery used for wire drawing and multiple die machines are now in common prac tice. In order to minimize oxidation and scaling, special types of annealing furnaces are employed for annealing the coils between the drawing operations. The Bates-Peard furnace is a typical example of the type of plant used, and consists of a gas-fired furnace chamber, the ends of which pass beneath water seals. The coils of wire are fixed to a moving chain which passes through the water seal into the furnace chamber; the furnace is continuous in operation, the coils passing slowly from one end to the other on the moving chain, and passing out through the water seal at the opposite end where they are quenched. Anneal ing by this method preserves the bright surface on the wire, and avoids any loss due to oxidation and scale. A considerable quan tity of copper wire is marketed in the form of bare coils in the half-hard condition, but there is also a considerable tonnage which is subsequently covered with paper, cotton, silk, rubber or other insulating material for use in the form of covered con ductors. Much of the wire is also supplied stranded, and all these operations are carried out on special machines which are largely automatic in operation. The machines consist essentially of a number of drums on which the wire or covering material is wound, and these drums are arranged so that they can be rotated on an axis through the central core as this passes through the machine. As the coils rotate round the core, the strands of wire or the covering material are automatically fed out under tension, and wind themselves round the core or central wire.

The cables have now, in many cases, to undergo a special process to render them as impervious as possible to moisture and at a later stage they may receive an outer protective covering, lead being the final protection in many instances. Lead covering is extruded on to the outside of the cable by means of a special pressure extruding plant. For immersion under water an addi tional protection has sometimes to be given in the form of hemp or metal armouring. Various designs of multiple cored and other special types of cable are manufactured and supplied for various purposes. The electrical industries also consume large quantities of bare copper strip for incorporation in electrical machinery. In the narrow widths and thicker gauges this form of the metal is produced mainly from wire bars which are rolled in a similar type of mill to that used for the production of wire. In addition, copper strip of greater width and much thinner gauge is produced in long lengths, and is usually supplied in the form of coils.

The term copper "strip" as distinct from copper "sheet" is usually assumed to apply to material less than 24 in. wide which is supplied in the form of long lengths. The majority of the strip used is under 12 in. wide and is manufactured by a process which has not yet found application in the rolling of material over 3 ft. in width. In the preliminary stages, the copper castings are rolled hot but in the later stages of manufacture, all the rolling is carried out cold, the material being coiled on coiling drums on each side of the rolling mills. Material produced by this method is of very even gauge and possesses an exceptionally good surface finish. The coils can be easily handled and are in general use for the manufacture of stampings, both in the electrical and other industries. Copper strip is supplied in various degrees of hardness according to the rolling it has received sub sequent to the last annealing. The usual grades of hardness or temper are termed soft, quarter-hard, half-hard, three-quarters hard and hard. These various tempers are selected according to the amount of subsequent mechanical deformation to which they will be subjected. Copper sheets are produced by somewhat similar methods of manufacture, and in America especially, the majority of copper sheets are made from electrolytic copper, but in Europe fire-refined arsenical copper is used very largely in the manufacture of sheets and plates. American and English practice is to use relatively small castings from i cwt. to 4 cwt. in weight, which are rolled out and cut to size. Both hot rolling and cold rolling is practised, depending on the surface of the sheet required, but American practice is tending more and more to use cold rolling for the final stages in sheet production, irre spective of the surface finish required. In Europe several finishes are marketed; the hot rolled and descaled sheet is known as ordinary quality and has a distinct red colour which is greatly valued in certain parts of the world. The red coloration is due to a thin film of cuprous oxide, which is easily removed by im mersion in dilute acid, and sheets cleaned in this way, known as acid cleaned or dipped sheets, are gaining favour for many purposes, especially when they have to be tinned or soldered. The so-called "ash" copper is a special finish obtained by annealing the sheets in air-tight packs, sheets annealed in this manner having an exceptionally adherent coating of cuprous oxide, which gives them a distinctive red colour.

Cold Rolling.—Cold rolling is an operation carried out sub sequent to hot rolling, and gives a sheet with an exceptionally smooth, bright finish, suitable for working up into highly polished articles. Cold-rolled sheets are manufactured in a variety of tempers similar to those already quoted for strip copper. In Europe methods have been developed to allow the use of large castings up to several tons in weight for sheet manufacture, and progress is also being made in the manufacture by strip rolling methods of much greater widths than have previously been attempted. In this method of manufacture the greater part of the rolling is a modified form of cold rolling, and the resultant sheets show a surface finish which is smoother than that obtained by the ordinary methods of hot rolling. In the thicker gauges, copper sheets find application in many industries, and are manu factured into pans and vessels of all kinds. The high heat con ductivity of copper is of great value for such purposes, in addi tion to which the malleable nature of the metal allows it to he worked into very intricate shapes. Where the metal is subjected to furnace gases and relatively high temperatures, it is generally considered that pure copper is not as satisfactory as arsenical copper containing approximately .5% arsenic. This applies also to the use of copper in locomotive fire-boxes. The Engineering Standards specifications and the British railway specifications re quire the metal t6 contain .3% to •5% arsenic. Copper is used almost exclusively for British locomotives' fire-boxes, and also by many foreign railways. The plates used in their construction vary in thickness from in. to I in., and undergo a very rigid testing before acceptance. Where alkaline waters are used, copper nickel alloys are coming into favour, as it has been found that they withstand these conditions better and have a longer life than the ordinary arsenical copper fire-boxes.

The use of copper for ordinary cooking utensils has declined owing to the competition of other metals, but its use still remains an important factor in the consumption of the metal in the Eastern market owing to religious rites which necessitate food being cooked in metallic vessels. A large tonnage of copper is exported annually from Europe in the form of circles and square sheets for consumption in India and the Eastern market, and owing to the severe hand working to which this material is sub jected it requires to be of high quality.

As one of the most malleable of common metals, copper is of great utility for working up by hand or by mechanical means into various shapes, and its increased use is mainly prevented by its cost as compared with other competitive metals. In general, however, the main qualities on which its use depends are its malleability, high heat conductivity and relative resistance to corrosion.

Alloys of Copper.—These are the most generally used of all non-ferrous alloys and comprise mixtures of copper with zinc, tin, nickel, aluminium, lead, iron, manganese and phosphorus. In many instances they consist simply of binary alloys formed by the addition of one other metal to copper, but in other cases two or more metals may be added in order to impart certain special properties. The principal series of alloys in which copper forms the chief constituent are brass (copper-zinc), bronze (copper-tin) and German or nickel silver (copper-zinc-nickel) (qq.v.). In addition to these better known alloys, there are many others which are finding increasing application in industry as their properties become more widely recognized. Those of copper and nickel afford a typical example of this kind, and their manufacture has greatly increased during the loth century. Owing to the fact that copper and nickel are completely miscible in the solid state, forming a complete series of solid solutions, the useful range of alloys is not confined within any definite limits of composition, although certain compositions have come into general use. Addi tions of 2-15% nickel to copper provide a series of alloys which are considerably stronger and more resistant to oxidation at high temperatures than copper. These alloys possess the additional quality of greater resistance to corrosion in alkaline water than arsenical copper, and have been adopted for locomotive fire-box manufacture where these conditions are encountered. The alloy formed of 20% nickel with the remainder copper is one of the most ductile of commercial alloys, and may be subjected to the most severe cold-working without the need of any intermediate annealing. It is also readily forged and rolled at a temperature above 800° C. These properties make it a very suitable alloy for drop forgings and cold stamping and pressing, and it has a variety of uses in automobile construction for exposed fittings as it takes a high polish and is resistant to atmospheric tarnishing. Other uses include bullet sheathing, for which purpose it is used by many nations including Great Britain and France. In the form of tubes its use is being rapidly extended for steam con densers, although the alloys containing 25% nickel and 3o% nickel are stated by some authorities to give better results as condenser tubing than the softer and less resistant alloys of lower nickel content. The chief use of the 25% nickel alloy has been for coinage, and several of the British colonies employ it largely because of its resistance to corrosion. The alloy containing 40% nickel has become very widely known under the name "Constanten." It has a high electrical resistance which remains practically constant over an appreciable range of temperature. This property renders it of value to the electrical industry, in addition to which its resistance to corrosion by organic acids and its silvery white colour when polished are causing it to be em ployed in increasing quantities for table-ware that has not to be silver-plated.

Monel metal (q.v.) is a so-called "natural alloy" prepared by the reduction of a copper-nickel ore and containing 6o%-7o% nickel. In addition to copper and nickel it contains iron and manganese in small amounts, together with other impurities which influence its properties to some extent. It has been widely used in America for various engineering and culinary purposes, and possesses exceptionally high strength at both normal and elevated temperatures. Alloys of similar nickel content are also being manufactured from the pure metals.

Copper also forms an important series of alloys with aluminium which are classed under the general term "aluminium bronzes" (q.v.). The properties of these alloys have been the subject of numerous scientific investigations which have shown that the use ful alloys rich in copper contain up to i I % aluminium. They may be classified into two main groups: those containing up to 7.5% aluminium are extremely ductile, whilst those containing 8%– I I % aluminium possess high tensile strength in the cast state. The ductile series containing less than 7.5% aluminium are especially useful for deep stamping, spinning and severe cold working of all kinds, and are finding application as a substitute for brass, compared with which they possess greater strength and resistance to atmospheric corrosion. The new bronze coinage introduced in France contains 8.25% aluminium together with a little man ganese, and this mixture approaches very nearly the upper limit for satisfactory cold working. The alloys with 8%–r i % aluminium usually contain in addition I%-3% of iron and are in very general use for die-castings, for which their high tensile strength and clean casting properties are a great advantage. They are resistant to corrosion by mineral acids and also resist oxidation at relatively high temperatures.

In addition to the alloys mentioned, copper is the standard alloying material used for gold and silver although the new British silver coinage also contains nickel. Manganese copper containing 3%-5% manganese is used in the form of rod by many continental railways for the manufacture of locomotive stay-bolts as it is relatively resistant to oxidation and retains its strength at moderate temperatures. Manganin contains 17% manganese, I%-2% nickel and the remainder copper, and has been extensively used for electrical resistances. It possesses the property of having a practically negligible temperature coefficient of electrical resistance at normal temperatures. There are also numerous more complex alloys containing three or more metals, such as the propeller bronzes, manganese bronzes, phosphor bronzes, lead bronzes, etc., the properties of which render them particularly suitable for the purpose for which they are designed. Such alloys do not represent any important tonnage but their development is an indication of the progress of metallurgical science in providing materials to meet modern requirements. (See BRASS ; ALLOYS ; ZINC; NICKEL ; ALUMINIUM, etc.) (C. A. E.)