Spectroscopy Roentgen Ray

SPECTROSCOPY : ROENTGEN RAY.) By placing the X-ray tube be fore the slits in place of the radiator, the spectrum of the primary X-rays can be compared with that of the scattered rays.

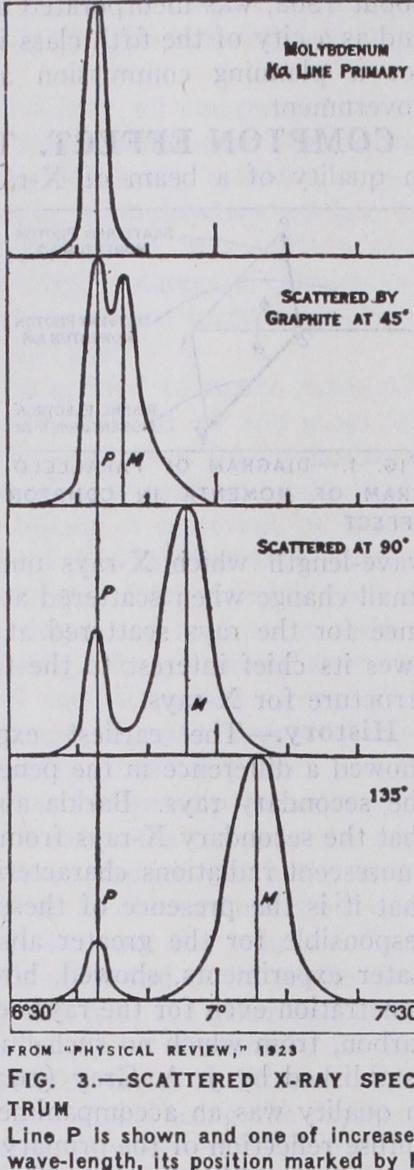

Fig. 3 compares the spectrum of the primary X-rays with the spectrum of these rays after they have been scattered by a block of graphite. The upper curve shows a prominent line in the X-ray spectrum of molybdenum. The lower curves show the spectrum of these rays after being scattered from graphite at three different angles. In each case, in addition to a line of the original wave length, there appears a more prominent line of increased wave length. Measurements on spectra of this type have shown that the difference in wave-length between the two sets of lines is given accurately by the formula 2.42 X 1 X (1 — cos4) cm. as predicted by the photon theory.

The line whose wave-length has not been changed is called the "unmodified" line. It may be accounted for as due to photons de flected by electrons that are too tightly held in the atom to recoil from the impact of the photon.

The Recoil Electrons.

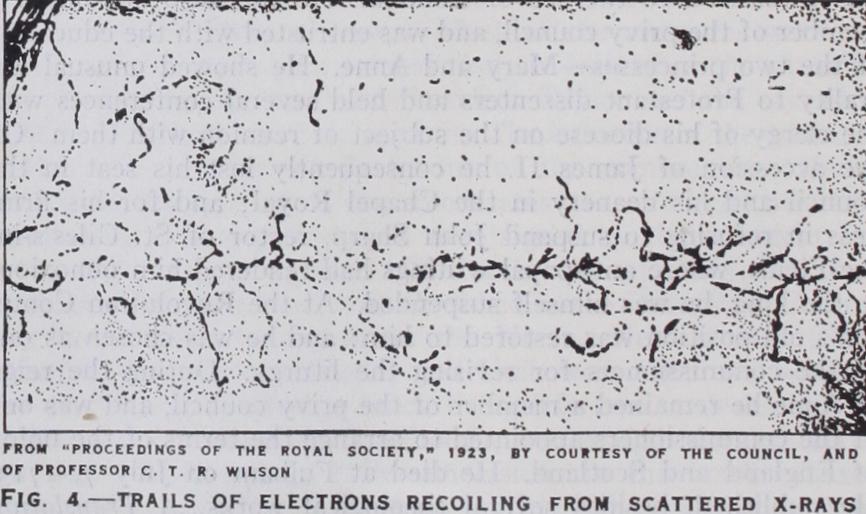

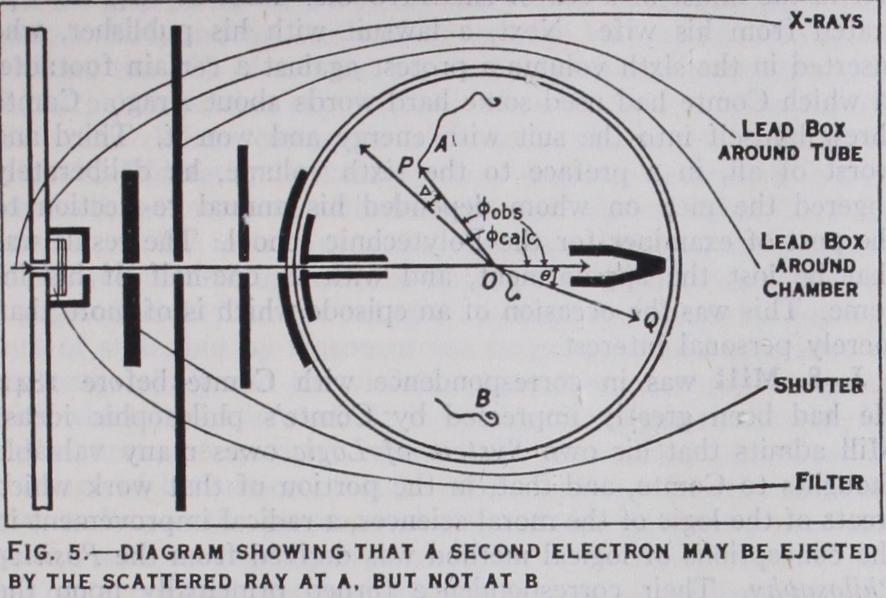

We have seen that, according to the photon theory, when an X-ray particle collides with an electron, the electron recoils from the impact unless held too tightly by its atom. Electrons recoiling in this manner were discovered inde pendently by C. T. R. Wilson and W. Bothe (1923) a few months after their prediction. Fig. 4 is a photograph of the trails of four such recoil electrons, taken by Ikeuti, using Wilson's method. It will be seen that the tracks of these electrons start nearly in the direction of the X-ray beam, as they should if they are recoiling from deflected X-ray photons. In fact a detailed study of such photographs shows that the number of these trails is about equal to the number of photons of scattered X-rays, and that their directions and ranges are in good accord with the predictions of the photon theory.The corpuscular character of the scattered X-rays is shown most clearly by tracing the path of a photon after it has collided with an electron. This has been done (Compton and Simon, 192 5) in the manner shown diagrammatically in fig. 5. A feeble beam of X-rays is admitted into a cloud expansion chamber of the type devised by Wilson to show the trails left by fast moving electrons. A photon is scattered by an electron at 0, and the trail of the electron as it recoils is visible. If it starts along the line OQ, the X-ray particle must have proceeded in the direction OP, determined by the usual mechanical laws of elastic collisions. The deflected photon can make itself visible by exciting a second high speed particle before it escapes through the wall of the chamber. The track at A represents such an occurrence. When such a sec onci track appears it is possible to trace the path followed by the X-ray particle after its collision with the first electron. If the scattered X-rays did not consist of particles, but were propagated as waves spreading in all directions, when a second electron ap pears, there is no more reason why it should occur at A than at some other position such as B. The fact that in the experiments the scattered ray excited secondary electrons near the line OP, determined by the angle of recoil 0, means that the X-rays go in definite directions.

Unless there is some improbably large error in the experiments, we may therefore infer that scattered X-rays go as discrete parti cles in definite directions. At the same time, experiments on the diffraction, interference and polarization of light and X-rays, and on electrical oscillations associated with electric waves, can leave no doubt but that electromagnetic radiation has the properties of waves. No satisfactory explanation has as yet been offered of how radiation may have at the same time the properties of waves and those of particles. Such a reconciliation does not, however, seem impossible.

The Photon.

The experiments associated with the Compton Effect thus seem to establish the existence of a particle of radia tion. This particle, the photon, may be classified with the electron and the proton as one of the three fundamental units of matter. It does not possess an electric charge as do the electron and the proton, but it does have an electric "field," that is, it exerts a force on an electron in its neighbourhood. It also has mass, the essential characteristic of matter, its mass being 2.19 X I X grams, where X is the wave-length of the radiation expressed in centimeters. For a hard gamma ray, of wave-length 2.4X cm., its mass is equal to that of an electron at rest; but for or dinary light its mass is only about o.000005 that of an electron. The photon seems to disappear when absorbed by an atom, and to be created again when the atom emits radiation. However, the suggestion has been made by G. N. Lewis (1926) that the photon is really retained by the atom and does not lose its identity. The motion of the photon is always with the speed of light, which in free space is about 3 X cm. per second.

Calculation of the Change of Wave-length of Scattered X-rays.—The photon theory can be put in quantitative form by making use of Einstein's postulate (19o5) that the energy of the photon is proportional to the frequency of the corresponding wave. Einstein assumes that the energy of a light particle is E = hv, where v is the number of vibrations per second of the corres ponding wave and h is a universal constant which has the value 6.S5X erg seconds. For a photon moving with the velocity of light, the theory of relativity demands that its momentum shall be E/c, where c is the velocity of light, i.e., the momentum of a photon is hv/c, or its equivalent h/X, where X is the wave-length of the corresponding wave. , The mathematical statement that the total energy after the collision between the photon and the electron is the same as before is, by = (I) where v' is the "frequency" of the photon after collision, and is the kinetic energy with which the electron recoils (neg lecting higher powers of which become important only when the electron's speed v is comparable with that of light) .

The statement that the total momentum of the photon and electron along the X axis remains equal to the hv/c after the col lision is, to the same degree of approximation, hv hv' —=— cos4+mv cos9 (2) c c Similarly, along the Y axis the momentum is hv' sin 4—mv sin 6 (3) In these three equations we have three unknown quantities, =v', v and 0 (in the experiments 4) is usually known), for which the equations may be solved. It is more convenient, however, to express the results of the solution thus: 6X =X'—X = h (I —cos 4)) = 2.42 X —cos (I)) (4) me Ek,n = = by X 2a cost 9(approx.) (5) cot 9= —(I+a) tan id), (6) where a=h/mc X. These equations represent the solutions of equations (I) , (2) and (3) except for higher powers of Equations (4) and (6) are exact solutions if the relativity expres sions for the kinetic energy and momentum of the electron are used.

Equation (4) expresses the difference in wave-length between the two sets of lines shown in fig. 3. It has been found to be as accurate as our knowledge of the constants, h, m, and c. Equation (5) describes the motion of the recoil electrons and has been found to agree with the experiments. The last equation (6) has been verified by experiments such as that pictured in fig. 5.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-A.

H. Compton, X-Rays and Electrons (1926) ; Bibliography.-A. H. Compton, X-Rays and Electrons (1926) ; E. N. da C. Andrade, The Structure of the Atom (1927) ; see also A. H. Compton, in Physical Review (1923) ; C. T. R. Wilson, in Proc. Roy. Spc. A. (1923) ; A. H. Compton and A. W. Simon, in Physical Review (1925), Bothe and Geiger, in Zeits. fur Physik (1925).(A. H. C.)