Superfamily Vi Lamellicornia

SUPERFAMILY VI. LAMELLICORNIA Antennae clubbed, the club composed of plates or comb-like . projections: legs stout and spiny, used for burrowing, tarsi 5 jointed. Larvae fleshy and cres centic with rather long legs.

There are three families of Lamellicornia as follows : The Lucanidae or stag beetles (fig, r g) are notable owing to the great development of the man dibles in the males, in which sex they are often antler-like in form : the use of these organs is problematical. The antennae are elbowed and the elytra cover the apex of the abdomen ; their lar vae inhabit decaying trees or their roots.

The Passalidae are confined to tropical forests : unlike the Lu canidae they have striated elytra and the jaws in the two sexes are alike. Their larvae live gregariously in wood and are tended by the parent beetles.

The Scarabaeidae (fig. 20) number over 14,000 species : the rose chafer, cockchafer and the "dor" beetles are familiar ex amples, while the sacred beetles or scarabs of ancient Egypt also find their place here. They are somewhat convex with very short antennae which are not elbowed, and the elytra do not cover the apex of the abdomen. The Scarabaeus has been studied by J. H. Fabre and the female beetles collect dung into balls which they roll along the ground and store in the earth as food for themselves and their larvae. The African goliath beetles (fig. 21) are among the largest of all insects. The larvae in this family feed upon dung, rotting wood, etc., or at the roots of plants : the latter habit prevails among cockchafers and great in jury to crops may result.

Reproduction and

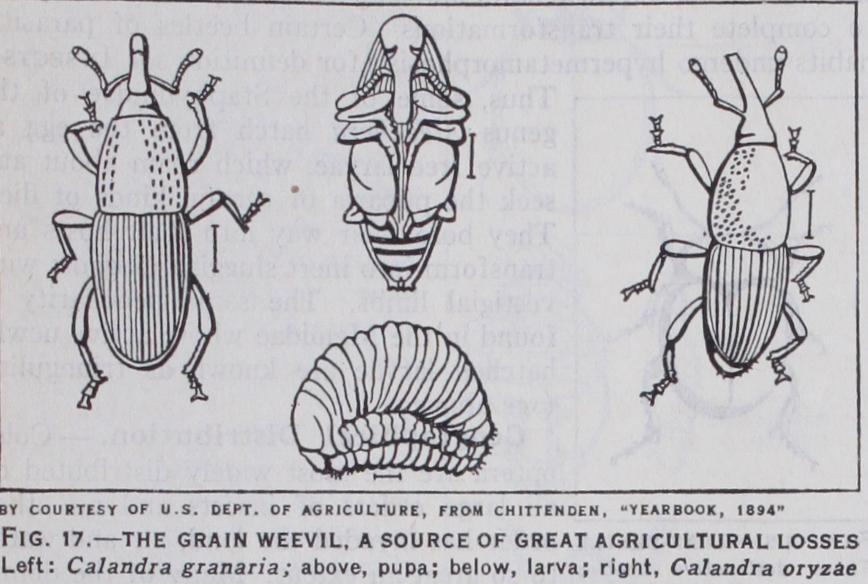

The eggs of beetles are laid in all kinds of places and most of them are ovoid out special features. Beetles are nct very prolific and, although the oil beetles may lay several thousand eggs apiece, this is exceptional. By ladybirds the eggs are laid in batches on leaves, some water beetles enclose their eggs in a kind of cocoon, while many weevils lay them in deep holes, drilled by the rostrum of the female, in the food plants. All beetles undergo plete metamorphosis and their larvae vary greatly in character (fig. 22). They may be active and seek out their prey, as in the ground beetles, tiger beetles and ladybirds (figs. 22 and 23) . Others, such as the chafers (fig. 22), have sluggish larvae, and live below ground or in rotting wood : although possessed of well formed legs they seldom seem to use them. 'In the weevils the larvae are legless maggots (fig. 22), ing in close association with their food. When fully fed, beetle larvae transform into generally pale-coloured, very thin-skinned pupae which have the appendages free (fig. 17). Such pupae are commonly found without a special cocoon in the soil or in whatever material the larvae fed upon. In some cases earthen protective cells are constructed or a loose cocoon of wood or debris, while a few weevils form attractive net-like or seed-like cocoons attached to their f ood-plants.As a general rule, beetles have a single generation in the year and many of them hibernate as adults under bark, in moss, etc.

Some species, such as certain bean weevils and the cotton boll weevil, may complete their life-cycle in a few weeks, and there results a number of broods in the year : the same remark applies to certain beetles living under warm conditions in stored grain. On the other hand, the cockchafer and stag beetle require several years to complete their transformations. Certain beetles of parasitic habits undergo hypermetamorphosis (for definition see INSECTS). Thus, some of the Staphylinidae of the genus Aleochara hatch from the egg as active free larvae, which roam about and seek the puparia of certain kinds of flies. They bore their way into their hosts and transform into inert sluggish maggots with vestigial limbs. The same peculiarity is found in the Meloidae whose active newly hatched larvae are known as triungulins (see above) .

Geographical Distribution..

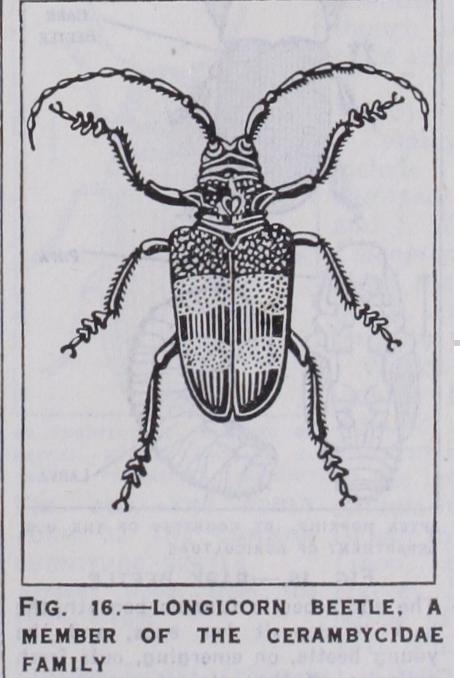

Cole optera are the most widely distributed of all large orders of insects and no other order has invaded the land, air and water to so great an extent. Many of the domi nant families such as the Carabidae (ground beetles), Curculionidae (weevils) and Scarabaeidae (chafers) are almost as widely distributed as the order itself. On the other hand, the Dytis cidae (water beetles) are more abundant on the northern conti nents, while the Cicindelidae (tiger beetles), Buprestidae, Ceram bycidae (longicorns) and Lucanidae (stag beetles) are essentially tropical families, becoming scarcer in more temperate zones. Some of the smaller families, however, are very restricted in their range, the Proterhinidae (closely allied to the weevils), for example, being almost confined to the Hawaiian Islands, and the aquatic family Amphizoidae only occurring in parts of N. America and Thibet. Certain species of beetles of diverse families appear more toler ant of climatic differences than others, and about Soo kinds are common to Europe, N. America and northern Asia. Many have become widely spread through the agency of man and over 1 oo species, more especially those affecting grain and other stored products, are now practically cosmopolitan. The study of island life yields some interesting fea tures relative to the distribution of beetles. Thus, in the Madeira Islands, Wollaston found 58o species of Coleoptera, and of these, 266 kinds are peculiar to those islands, although allied to European species : in the Hawai ian Islands, Sharp mentions 428 species among which 352 species have not so far been found else where. Thus the peculiar species must have formerly existed else where, migrated to the islands mentioned, and since become ex tinct in their original homes, or they must have been evolved within the islands—the latter be ing the more probable.Geological Distribution.— The oldest known fossil beetles come from the Upper Permian beds of New South Wales and consist of elytra only: these remains have been referred to special families, unrepresented at the present day, and certain of them show affinities with the existing family Hydrophilidae. A great number of fossil remains of beetles have been found in the Upper Trias of Ipswich, Queensland, and in the Trias of Switzer.

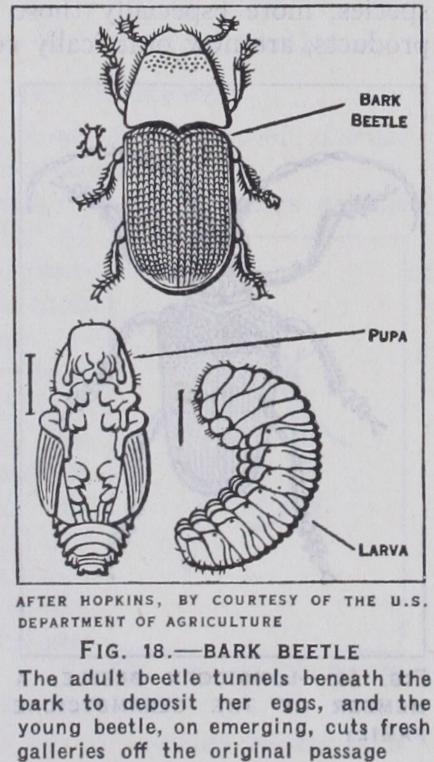

land. Some of these Triassic fossils are leaf-beetles and weevils, while the English Purbeck beds have yielded remains of bark beetles. In the Tertiary rocks of Colorado and Florissant and in the Prussian amber (Oligocene) many f ossils referable to living genera have been found, including about 400 species of weevils.

Natural History.

Beetles and their larvae live and feed in almost all the diverse ways found among insects. The carnivorous habit of seeking and devouring living prey occurs in the ground beetles, tiger beetles, ladybirds and in water-beetles of the family Dytiscidae. In these instances the beetles and their larvae have like habits. In certain rove beetles of the genus Aleochara, in the ground beetle Lebia scapularis and in the curious Metaecus para doxus (fam. Rhipiphoridae) the larvae are true parasites and the beetles free-living—a habit that is rare among Coleoptera. The Metaecus occurs in Britain and its newly hatched larva is a minute black, active creature which, by some unknown means, finds its way into wasps' nests. Here it becomes an internal parasite of the wasp grub and subsequently bores its way out of its host, finally devouring the remains. A vast number of beetles and their larvae feed directly upon plants : this is the case with the whole family of the Chrysomelidae, or leaf beetles, and with the weevils. Others, such as the Cerambycidae (longicorns), Scolytidae (bark beetles) and Buprestidae, feed in the larval stages upon the wood or bark of trees. Wireworms, or injurious Elaterid larvae, and chafer larvae feed on the roots of various crops. Weevils have very diverse habits and no parts of plants from the roots to the seeds are exempt from the attacks of one or more species. There is again a great and diverse assembly of beetles, and more especially their larvae, which feed entirely upon decay ing organic matter of various sorts. Thus the Silphidae include many carrion feeders and are well exemplified by the burying beetles ; hosts of rove beetles fre quent refuse of all kinds, and many Scarabaeidae live in dung. We have to add to these examples the many beetles and their larvae that live in grain and other stored products, and those attacking hides, furs, museum specimens, tobacco and drugs.

Apart from the more usual habits it is interesting to note cer tain exceptional modes of life found among beetles. There are genera and even whole families that live in the nests of ants or of termites. There are others that inhabit the extensive limestone caves of Europe and North Amer ica, while certain blind ground beetles are only met with beneath huge boulders deeply embedded in the earth. There are also species that inhabit the sea-shore and are submerged by the tides.

Means of protection against enemies are very varied among Coleoptera. Some are cryptically coloured and closely resemble their surroundings : thus in the African longicorn Petrognatha gigas the whole upper surface resembles dead velvety moss, and its irregular antennae are very like dried tendrils or twigs. Many weevils fall and feign death at the least alarm and, folding their limbs close around the body, look like seeds or particles of soil, thus escaping observation. There are again beetles, especially those living in ants' nests, that resemble ants, and the common wasp beetle of Europe, both in its move ments and colouration, closely resembles a wasp (for further instances of this kind see the article MimrcRY). There are other beetles which obtain some measure of pro tection possibly from their repellent ap pearance, or from their property of emit ting evil-smelling or distasteful secretions, either in the form of exudations of blood from definite parts of the body, or as the product of special foetid glands. The bombardier beetles (fam. Carabidae) have the property of secreting an evil smelling defensive fluid from the anal end of the body. In some cases this fluid volatilizes into a gas which appears like a minute jet of smoke when it comes into contact with the air, and its caustic properties act as a repellent to other insects or foes. Finally a number of beetles secure protection in virtue of their general agility of movement—thus, many ground beetles and tiger beetles run rapidly and the latter also take to the wing with great readiness, while the flea-beetles have remarkable powers of leaping.

Many beetles are capable of sound-pro duction which is usually brought about by the friction of one part of the body (the "scraper") against another part (the "file"). These stridulating organs have been studied by C. Darwin and more re cently ( 9oo) by C. J. Gahan : they are generally present in both sexes and prob ably serve f or mutual sexual calling. In some beetles there is a file-like area on the head which is rasped by the anterior mar gin of the prothorax. Among the Cerambycidae (longicorns) the sound is produced either by rub bing the hind margin of the pro thorax over a striated area on the mesothorax, or by rubbing the femora of the hind legs against the margins of the elytra. Stridu lation, however, is not confined to adult beetles, but obtains in certain larvae also. Thus, in some larvae of the group Lamel licornia there is a series of ridges or tubercles on the coxae of the middle pair of legs and the hind legs are modified in various ways as rasping organs. In the cock chafer larva and larvae of other Scarabaeidae a ridged area on the mandible is rasped by a series of teeth on the maxillae. Stridu lation in larvae is quite inde pendent of sex and it has been suggested that it is to warn neighbouring larvae., inhabiting bb ru jArgrhpo tawri sit g hi fntr owf mo or o trdhe , ec oestgacnm. teit oopnuar pvb oyoi sdse oguerrnandi gs oi n ee a oc thh eo rt h be er e' stlwesaYeinit a e seat of the light is in special luminous organs which consist of an outer or light-producing layer, and an inner or reflector layer. The outer layer is supplied with oxygen by means of tracheae and the reflector layer contains many urate crystals which appear to act as a background, scattering the light and preventing its dispersion internally. The light is pro duced as the result of the oxidation of a compound loci f erin in the presence of an enzyme-like substance luci f erase, which takes place in the outer layer of the lumi nous organ. It has been suggested that this property does not reside in the actual cells of the tissue concerned, but is due to the pres ence therein of special luminous bacteria. Luminous beetles be long to the families Cantharidae and Elateridae and a familiar ex ample of the first mentioned f am ily is the common European glow-worm Lampyris noctiluca, whose wingless female emits a bright light near the hind end of the body : its winged male ex hibits a much feebler luminosity. The luminous Elateridae include the fire-flies of the genera Pyro phorus and Photophorus, both sexes of which are winged and luminous.

Economic

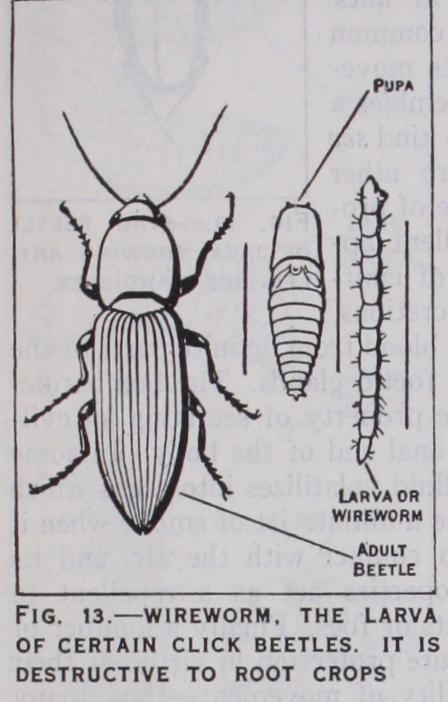

Beetles include among their cies many that are injurious, either as larvae or often as adults also. Among those which attack farm crops, wireworms, or ious larvae of certain click beetles are severe pests of the farmer. They are most prevalent in newly ploughed grassland and attack the supervening crops, particularly cereals and roots. Flea beetles (fam. Chrysomelidae) cause great injuries to plants of the turnip tribe, both the beetles and their larvae feeding upon the leaves and other parts. The asparagus beetle (Crioceris asparagi), belonging to the same family, is a familiar pest with growers of that vegetable in Europe and N. America (fig. 24) . Related to it is the orado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa lineata) which is destructive to potato foliage in the eastern half of N. America: quite recently it has become established in the Bordeaux district of France. The Japanese beetle (Popillia japonica), one of the chafers, was accidentally introduced into New Jersey, from Japan, about 1916 and is extending its range in N. America where the beetle is injurious to the foliage of fruit and other trees, and its ground larvae damage lawns and golf greens. The common cockchafer lontha vulgaris) and its allies are European pests whose larvae devour the roots of farm and other crops, the beetles feeding upon the foliage of trees. Many weevils are highly injurious : thus, the cotton boll weevil (Anthonomus grandis) is the most serious enemy of the American cotton crop. It entered Texas about 1892 from tropical America, sequently infesting almost the whole cotton belt. In England, and other parts of Europe, its ally the apple blossom weevil (A. pomorum) prevents the formation of large quantities of fruit. The palm weevil (Rhynchophorus ferrugineus) infests toddy and cocoa-nut palms, and the pine weevil (Hylobius abietis) is extremely harmful to young conifers in Great Britain.Various members of the Scolytidae (bark beetles) are wide spread pests of forest trees : one species (Xyleborus fornicatus) is the shot-hole borer of tea in Ceylon. Larvae of many Ceram bycidae (longicorns) are also destructive to living and dead tim ber, while species of Anobium and Xestobiurn (death watch beetles) bore into furniture and the rafters of public buildings (fig. 25A) : the powder post beetles (Lyctidae) have very similar habits. Many beetles also attack stored grain, meal and other dried products, no tably the granary weevils (Calandra) and the meal-worms and their allies (f am. Tenebrionidae).

The above remarks serve to show the many injurious species of Coleoptera ; nev ertheless, there are others which have been employed by man to his own benefit. The Australian ladybird (Novius cardinalis) has been imported into most citrus-growing countries of the world for the purpose of controlling the fluted scale which it attacks and destroys to a re markable degree. Another Australian ladybird (Cryptolaemus montrouzieri) has a similar habit of preying upon mealy bugs (Coccidae), and its introduction into the Hawaiian Islands and California has achieved a re markable degree of s u c c es s. The European ground beetle Calosoma sycophants has been introduced into N. America, where it preys upon the cater pillars of the gipsy moth and brown-tail moth. Mention must also be made of another type of useful beetle viz. the Spanish fly (Lytta vesicatoria) which yields cantharidin.