The Physical Nature of Comets

THE PHYSICAL NATURE OF COMETS When predicting the circumstances of the return of a periodic comet, the assumption is made that no force is acting upon it except the gravitational attraction of the sun and planets. The assumption is justified by the fact that in all such cases where the previous appearances of the comet have been well ob served, and where the perturbations have been carefully computed, the prediction is close to the truth. On the other hand, study of the tails of comets shows that they are acted on by a repulsive force from the sun, which is in many cases much stronger than the gravitational force. It is concluded that the tail is composed of matter in a much more finely divided state than the head, and that the head is made up of fairly large lumps, for which the repulsive force is negligible compared with the gravitational. We are led to the same conclusion in two other ways.

First, the matter driven out into the tail is clearly lost to the comet, whose attraction is quite inadequate to bring it back from the great distances to which it is sent ; but large comets, like that of Halley, continue to emit new tails at each approach to the sun. Hence the head must have reservoirs to contain this gas, and give some of it off at each approach. Meteoric masses, when analysed, are often found to contain hydrogen and other gases, so that it is reasonable to conclude that a comet's head is formed of similar masses.

Secondly, when orbits were calculated for the leading showers of meteors, it was found in many cases that they agreed closely with the orbit of some comet, and in the case of the Leonid me teors the year of maximum display, 1866, coincided with the peri helion passage of the comet. Since we do not see meteors unless they enter the earth's atmosphere, we can see only the meteors belonging to those comets whose orbits approach that of the earth; but we may infer their existence in other cases. The meteoric lumps are probably some feet in diameter, comparable with those large meteoric masses that have fallen to earth from time to time; specimens are exhibited at the Natural History Museum, South Kensington, and elsewhere. Lumps of a much smaller size would hardly retain a plentiful supply of gas for thousands of years, such as we infer to have been given out by Halley's comet from the accounts of immense tails at many of its returns. We cannot imagine the diameter of the lumps to run into miles since some sign of them would then have been visible when that comet transitted the sun in 191o.

There are two suggestions as to the nature of the repulsive force that drives out the tail; these are radiation pressure and electrical repulsion. The amount of the accelerative action has been measured by taking photographs at short intervals, and noting the outward movement of luminous knots in the tail; esti mates as high as So times that due to gravity have been obtained, which is higher than the acceleration that radiation pressure could produce. There is another proof that other forces are at work in driving out the tail. It is easy to prove that all matter driven from the comet's head by solar action would leave the head along the line from the sun to the comet; but it is quite common for the tail to consist of several streamers radiating from the head like a fan, the outer ones making a considerable angle with the line from the sun.

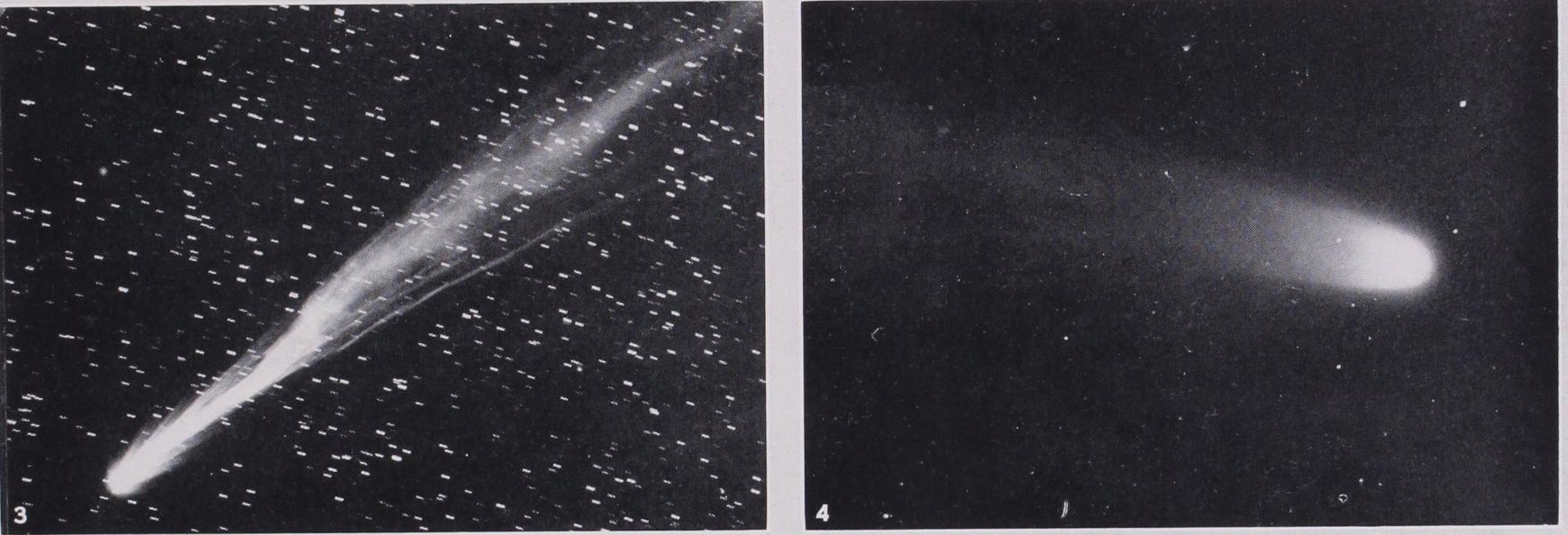

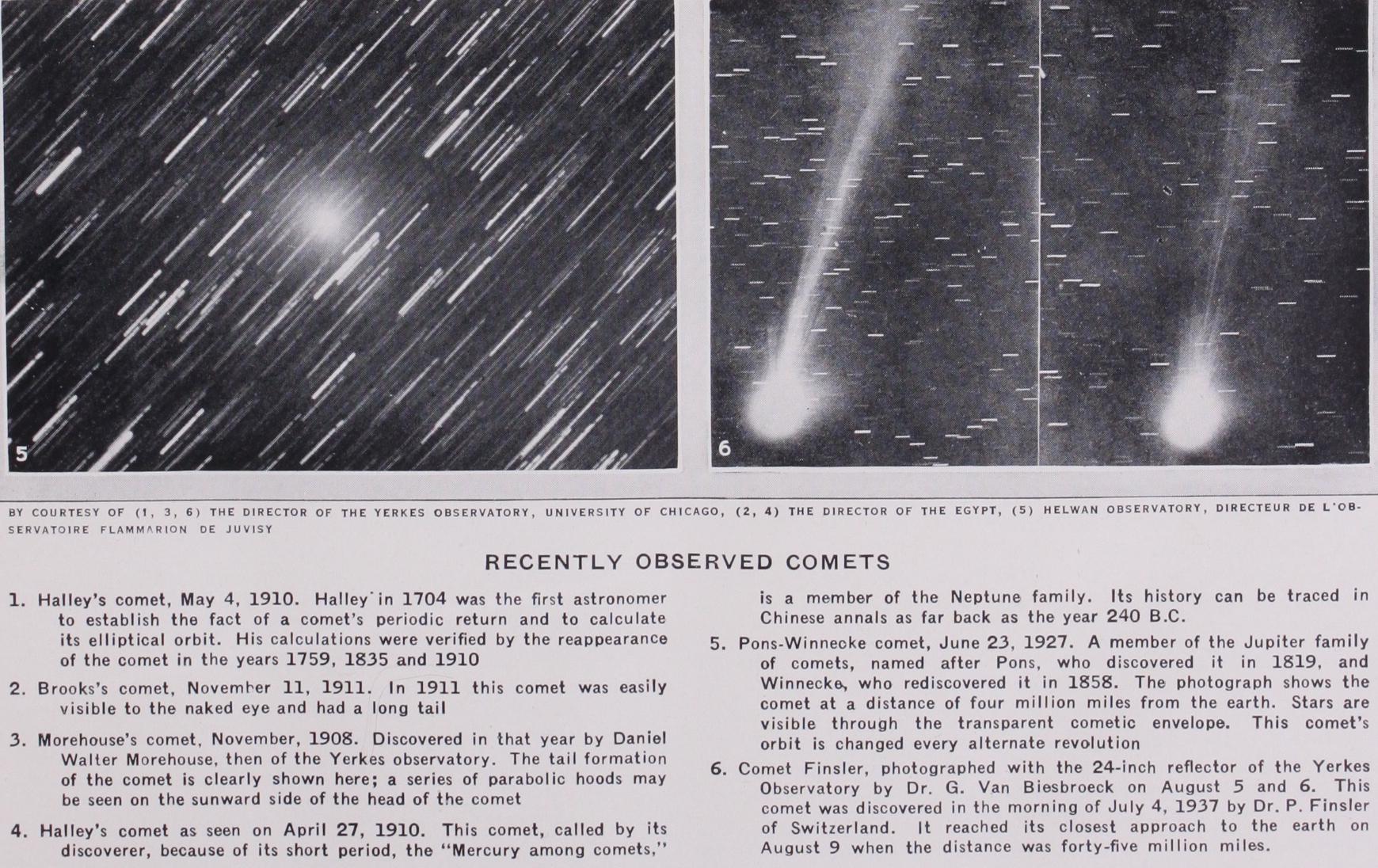

The force expelling these streamers must be situated in the head, and electrical repulsion is the most probable solution. More house's comet of i9o8 was a specially favourable one for studying tail formation; it would seem that most of the matter leaves the head on the sunward side, but is soon bent back by the solar repulsive action. The action is like that of the jets in a f ountain, shot up by water pressure, and curved downwards by grav ity. When looking at the congeries of jets in the fountain we see that their outline is parabolic; in just the same manner we fre quently see a series of parabolic hoods on the sunward side of the comet's head. These hoods are clearly shown in the photo graphs of Morehouse's comet of go8, and in the drawings of those of 1874 and 1881.

The emission of tail matter is not continuous, but intermit tent; in Morehouse's comet, and in Halley's (I 9i o) the. photo graphs showed discarded tails, with a space between them and the new tail. Halley's comet also lost its tail on Jan. 24, 1836, and there were rapid changes of appearance, which would seem to have had their seat in the nucleus. Holmes's comet of 1892 exhibited very remarkable changes, which were the more notable since it was distant from the sun, in the middle of the zone of asteroids. It suddenly attained naked eye visibility, though it had been equally well placed for observation for some weeks without anything being seen of it. There must have been something of the nature of an explosion in the nucleus, causing a great out rush of diffused matter which at first was very bright, but grew fainter as it expanded till it could no longer be discerned; then a second outburst took place, repeating the course of the first on a smaller scale. The comet was seen again in Sgo and go6, but it never repeated the remarkable outbursts of its first apparition.

The comet of 1744 had six divergent tails; this was looked on at that time as very abnormal, and those who did not see the comet received the accounts with incredulity. But photographs show that multiple tails are quite common, though the outside ones are seldom so conspicuous as in 1744.

Comets in the Spectroscope.

The spectroscope indicates that most of the light of the nucleus is reflected sunlight; but most of that from the gaseous envelopes gives a spectrum of bright bands. These have been identified with those of carbon monoxide, cyano gen and hydrocarbons. At a moderate distance from the sun (half the earth's distance, or less) the spectrum of sodium usually becomes visible; it was conspicuous in Wells's comet of 1882, and gave the comet a yellowish colour. When a comet comes very near the sun, as in the great comet of 1882, the spectrum of metals, including iron, becomes visible. It will be remembered that iron is an important constituent of many meteors. The Rus sian astronomer, Theodore Bredichin, published a theory of com ets' tails in which he postulated a hydrogen composition. for long straight tails, a hydrocarbon one for those of intermediate type, and iron or other heavy substance for short, highly curved tails. The spectroscope hardly confirms this in details, since it does not reveal the presence of pure hydrogen; moreover, spectro scopic photographs taken with a prismatic camera do not.indica.te notable difference between the compositions of neighbounng tails.

Gradual Diffusion of Cometary Matter.

There are two distinct ways in which cometary material becomes scattered; the tails evidently consist of very finely-divided matter, either gas or fine dust, since here the non-gravitational forces predominate over gravitation. But meteors continue to follow gravitational orbits; hence they consist of much larger particles, similar to those form ing the comet's head, on which we have seen that gravitation is in control. The large dispersion of the meteors away from the comet's head is surprising, and must have taken a long time to complete. Thus in both the November Leonid shower (Tempel's comet), and the August Perseid one (Tuttle's comet), the meteors form a complete ring round the whole orbit, though they are more densely packed in the neighbourhood of the comet. So also the Aquarid meteors of May, whose connection with Halley's comet is admitted, travel in paths separated from that of the comet by many millions of miles. The cause of the beginning of this scattering action is obscure, but once it had started it would proceed with accelerated pace, since the attraction of the sun and planets on the different portions would henceforth be appre ciably different. We become aware of the existence of meteors only when they enter the earth's atmosphere; hence only a small minority of comets yield visible meteors; but from analogy we may infer their existence with confidence in the case of all the periodic comets. It is more doubtful whether comets with sen sibly parabolic orbits are accompanied by meteor swarms.There are two ways in which comets may cease to exist as such. Either the meteors in the head may lose all their gas (this appears to be the case with Biela's) or these meteors may become so diffused and scattered as to lose all semblance of unity and coherence. We have no actual experience of the dissolution of a comet in the latter manner; in fact the coherence of the heads of some comets is surprisingly great, and seems to indicate some unknown force holding the constituents together. Thus the comet Pons-Winnecke has been known since 1819, and has made sev eral close approaches to Jupiter; further it has given rise to a meteor shower, which was well seen in June 1916. Yet when the comet approached very near the earth, in June 1927, its nucleus was seen to be very small, not more than two miles in diameter according to Prof. V. Slipher and M. Baldet.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-Practically all handbooks of astronomy have chapBibliography.-Practically all handbooks of astronomy have chap- ters on comets; reference can be made here only to books dealing specially with them; the first two books are of a popular character:— George F. Chambers, F.R.A.S., The Story of the Comets (Oxford, Iwo) ; Mary Proctor, F.R.A.S., The Romance of Comets (London and New York, 1926).

J. G. Galle, Verzeichniss der Elemente der bisher Berechneten Cometenbah.nen (1894), contains orbits of comets from 372 B.C. tO A.D. 1893, with copious notes in German. A sequel to Galle's Cometen bahnen, continuing it to A.D. 1925, published as vol. xxvi. part 2, of Memoirs of British Astronomical Association (Perth, 1925).

Bengt Stromgren, Tables for a motion in parabotic orbits, vol. xxvii. part 2, of Memoirs of British Astronomical Association (Perth, 1927). Prof. H. C. Plummer, Introductory Treatise on Dynamical Astron omy (Cambridge, 1918), contains much useful matter relating to orbits, but needs mathematical knowledge.

Prof. Charles P. Olivier, Meteors (Baltimore, 1925). The associa tion of meteors to comets is very close; there is much relating to comets in this book.

John Williams, Observations of comets (in China) from 61r B.c. to A.D. /640 0870. A. Pingre, Comitographie; ou Traite historique et theorique des Cometes (1783), contains much interesting matter relating to p.ncient and mediaeval comets, but is probably accessible only in libraries.

A full and simple (lescription of the method of finding orbits, both elliptical and parabolic, was given by Dr. G. Merton in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society for June 1925. Nothing is needed with it beycrid a nautical almanac and logarithm tables (or, if preferred, a calculating machine). (A. C. D. C.)