Theatrical Costume Design

COSTUME DESIGN, THEATRICAL. The early his tory of theatrical costume can no more be separated from that of religious and ceremonial costume than the early history of drama as a whole can be separated from the history of religion, which merges by slow degrees into drama. The first steps away from religion proper are usually taken in the direction of comedy, many gods becoming the clowns of future generations. The Etruscan devil dancer may easily be the descendant of a powerful god to whom bloody offerings once were made; yet the lineal descendant of this god played a clown's part as recently as so years ago in a Hungarian mystery play.

Where religion and drama interweave, it is difficult to deter mine to what extent the costumes of the priests and members of secret societies may be considered theatrical. How far the Egyp tian gods portrayed in bronze and stone represent priests dressed in the usual costume of the early dramatized gods remains largely a matter of conjecture. However, it seems logical that masked priests played a part in certain Egyptian mysteries. In the last few years numerous collections have been brought together of masks and costumes representing gods and demigods from differ ent mystery plays of almost all nations, including European coun tries. The frequent occurrence of these masks over the civilized world suggests that they were also used by the Egyptians.

At the beginning of drama in each country one finds masked re ligious figures, gods or heroes. Long before the Javanese wajang Wong there was the masked pantomime topeng dance. Long be fore the No performances in Japan existed, performances were given, within the temple, of the masked kagura dances. In China, in Mexico, in Greece and Central Europe, everywhere in fact, one comes across traces of the old religious costume in the drama of a more secular nature of much later date, so much so that it seems safe to regard the purely religious costume as the prototype of the more fantastic costumes in the secular and commercial theatre. Thus the temple dance in Japan through the No dramatic festival and the temple dance entertainment finally influenced the kabuki or popular theatre. Thus the religious images of the mediaeval church influenced the costuming of the municipal plays in the Low Countries during the I sth and early i6th centuries.

Oriental.

The Japanese No costumes and masks are largely preserved as temple treasures. They are among the most beautiful stage costumes ever made. As the No actor is held in popular esteem among the Japanese, whereas the actors in the popular theatre are regarded almost as outcasts, so the maker of the No masks is a highly esteemed artist who proudly signs his name to his work. Although the No dates from the 14th or early I sth cen tury, the masks that one sees usually are of a much later date. Besides the carved wooden lacquered masks the costumes consist of gorgeous brocades which are specially woven with large mediae val patterns, of beautifully wrought accessories, jewellery and fans. The combination of all these temple treasures, if worn by a fully apparelled No actor when he approaches with cadenced motions on the highly polished floor of the No stage, makes a spectacle never to be forgotten. The costume here, as in ancient Greece, China and Java, indicates through traditional accessories not only the rank or position of the actor but even the sex of the character he is to represent, as only men are permitted to take part in the performances.

The costumes worn in China are usually of embroidered silks and in a religious or semi-religious play they are even to-day of antique cut, with false jewellery and metal-work to make them look rich at a distance. In some of the congratulatory plays in China, where masks are worn, the number of masks is prescribed by tradition. There are four guardians, 28 patriarchs, 28 lunar gods, eight female fairies of such poetic names as Cinnamon Blossom, Pear Blossom, Lotus Flower, Spring Breeze, etc. In the commercial theatre the masks have been done away with, traditional make-up taking their place. The costumes also have been changed somewhat, the best known characters to Western eyes being the generals who are indicated by numbers of small flags which are arranged in a kind of halo on their backs. The prescribed make-up closely re sembles the painted scroll work one sees on the masks, which are used to indicate ancestral heroes.

In Tibet the lamas produce mystery plays at certain festi vals which include among the most characteristic figures a kind of buffoon, looking for all the world like a half decayed corpse. The type of masks and costumes used in the Tibetan mystery plays closely resembles that of the Chinese. In Siam and Cambodia the masks worn by the ballet have a religious meaning. The costumes themselves are provided with the most elaborate jewellery. In Java a strange in fluence has been exerted on the costumes in the wajang Wong drama by the prototype of this form of entertainment, viz., the cut leather shadow marionette perform ance. It was only in the i8th century that the plays belonging to this type of shadow theatre started to be enacted by men. The plays are all borrowed from Hindu sources, the heroes being represented with a curious kind of wings of pierced and gilded leather similar to the minutely cut golden filigree work of the leather shadow marionettes.

Animals play an important part in the per formances given by the native princes on festive occasions. The animal costumes are made of painted cloth on a bamboo frame-work. In the original topeng dances, which antedate the other performances by centuries, old court costumes are worn but all actors are masked to indicate the char acter and rank. It is only very recently that women have acted in the Javanese drama and then only in the commercial theatre, often in groups without men, which custom has also been introduced in China. The ballet dresses worn by the corps de ballet at the native courts do not differ from the regulation court dress, except for the addition of a very long brilliantly coloured scarf which is not usually worn by other women. The ballets given by these troupes are always private and the costumes are therefore de signed to appear well at close range, just as the modern ball-room performers usually wear the conventional dress, or the geishas of Japan wear fantastic costumes with no particular stage value.

Classical.

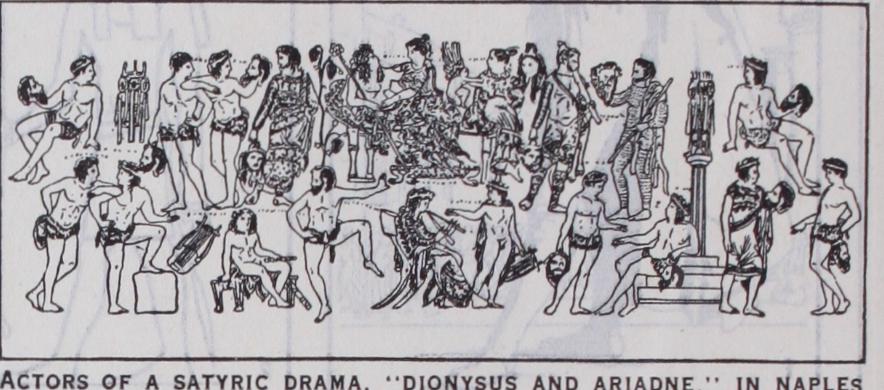

The ancient Greeks instead of using make-up availed themselves of masks to indicate the character of the actor like the Chinese and Japanese. Besides the mask there were various attributes by which one could recognize the character's position in the drama. As in the traditional make-up of the Chinese, colour played a large part in this symbolism. A typical part of the Greek actor's costume was a kind of stilt or wooden clog called the cothurnus, with which the actor's height was in creased by several inches, and the introduction of which was credited to Aeschylus. To increase his height further, a conical wig was arranged on top of the mask, this addition being called the onkos. In comedy the cothurnus was replaced by a different kind of shoe.

Everything about the costumes was traditional. If the play was a tragedy the actor wore an underdress or chiton, over that a draped gown, also a gold embroidered overdress. In addition to the dress proper, there were various hand properties, crowns, etc., which made it possible to distinguish the characters one from an other. Dionysus is reported to have worn a yellow overdress, a shoulder strap with flowers and a thyrsus. Other gods had their own attributes. If a character were supposed to be unfortunate he used dingy clothes, grey or faded blue, black or murky yellow. Queens were supposed to wear white and purple, other ladies saffron or frog green, these costumes being lavishly embroidered with gold. Satyrs wore goat skins, real or imitation panther skins, phallic attributes and red overdresses. The sileni wore, besides their tails, a curious underdress. In comedies the actors wore the chlamys over a plain white underdress, together with travelling hats and hair bands, and had properties such as bows, spears, knives, staffs, etc., to complete the costume. The number of masks were regulated by the Greeks also, apparently in a much more arbitrary way than among the Chinese. According to Pollux there were six old men, eight young men, three attendants and II women, making 28 in all. In the New Comedy there seem to have been nine old men, I I young men, seven slaves, three old women, 14 young women. The costumes also were very conven tional. The richness of the cos tumes, especially of the chorus, depended much on the wealth and good will of the choragus, who financed the performance sometimes as a civic duty which was laid upon rich citizens, but much more often for the glory which a successful production brought to the backer.

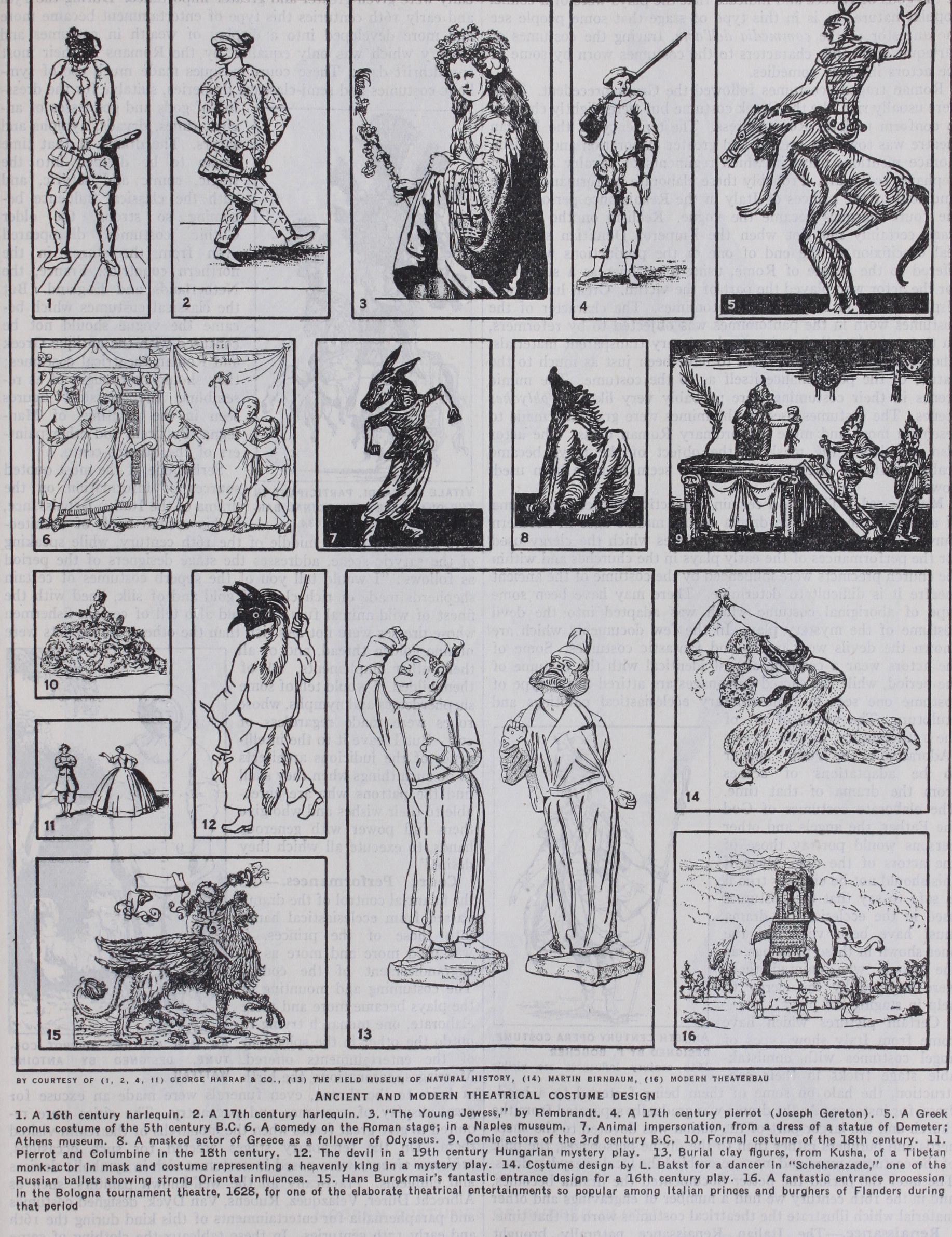

Although most of the performances were given by groups of actors living near the large theatre, travelling was done even into the distant colonies. As an offshoot of the orthodox theatre in Greece a kind of theatre called the phlyakes seems to have been established in southern Italy in the 3rd century B.C. Judging from the evidence on vases, we know that the costumes were caricatures of the gods of Greece and indicate that the plays were of a comic, popular nature. It is in this type of stage that some people see the ancestor of the commedia dell'arte, tracing the costumes of harlequin and other characters to the costumes worn by some of the actors in these comedies.

Roman tragedy costumes followed the Greek precedent. They were usually rich like the Greek costume but were slightly changed to conform to local Roman dress. The tendency of the Roman theatre was toward a greater and greater elaboration and realism. Horace mentions plays in which regiments of cavalry and even elephants took part. Probably these elaborate performances were emulated by the princes of Italy in the Renaissance period when the court masques became the vogue. Realism on the Roman stage certainly ran riot when the Emperor Domitian staged a real crucifixion at the end of one of the productions which he offered to the people of Rome, using a prisoner as a substitute for the actor who played the part of the victim. Great luxury was displayed also in the Roman pantomimes. The character of the costumes worn in the pantomimes was objected to by reformers, on the ground of their being made of very transparent materials. The objections, however, seem to have been just as much to the nature of the performance itself as to the costume. The mimic scenes in their costuming were probably very like the phlyakes scenes. The costumes used in the mimes were gradually made to resemble more and more the ordinary Roman dress. The actor also abandoned the mask as the object of the plays became realistic. In the Atellan farces masks seem to have been used, however.

Mediaeval.

There is a certain connection between the drama of ancient Rome and the drama of the middle ages in northern Europe, but to what degree the costumes which the clergy used for the performances of the early plays in the churches and within the church precincts were influenced by the costume of the ancient theatre it is difficult to determine. There may have been some type of aboriginal costume which was adapted into the devil costume of the mystery play. In the few documents which are known the devils wear masks and fantastic costumes. Some of the actors wear a costume almost identical with the costume of the period, while the sacred personages are attired in the type of costume one sees in contemporary ecclesiastical paintings and sculpture. The works of art of the sth century, as Van Eyck's "Adoration of the Lamb," appear to be adaptations of scenes from the drama of that time.The elaborate costumes of God the Father, the angels and other persons would portray those of the actors of the day. Even if this should not be entirely true it is safe to say that the costumes used in the ecclesiastical drama must have been very like the ones shown in these paintings, as the people who painted them were engaged by the clergy to help in staging the plays.

Certain pictures which have come from Italy show types of angel costumes with unmistak able stage tricks in their con struction, the halo on some of them being fastened to a head dress, for instance. As the drama was gradually separated from the church and the larger part of the action was devoted to the shep herds and burghers rather than to the divine personages, the bulk of the costumes more and more resembled the local everyday dress. The later the period the better documented the drama becomes, and in the 6th century we find a number of engravings and other material which illustrate the theatrical costumes worn at that time.

Renaissance.

The Italian Renaissance naturally brought about a radical change in stage costume. To the mediaeval tourna ments were usually added some dramatic interludes which grad ually were given greater and greater importance. During the i5th and early i6th centuries this type of entertainment became more and more developed into a display of wealth in costumes and scenery which was only equalled by the Romans in their most spendthrif t days. These court masques made much use of sym bolic costumes and semi-classical draperies, suitable for the dress ing of gods and goddesses of an cient times, dryads, nymphs and satyrs. The drama at that time began to be divided into the tragic, comic and satyric, and with the classical influence be coming so strong, the older Gothic costumes disappeared even from the stages in the northern countries, France, the Netherlands and England. But the classical costumes which be came the vogue should not be confused with the antique Greek and Roman theatrical costumes; they should be thought of as re sembling the classical figures seen in the paintings of Man tegna, Botticelli and other paint ers of the quattro-cento.Serlio, one of the most quoted sources of information on the drama of the Italian Renaissance, in his second book of architec ture published in the middle of the i6th century, while speaking of the satyric scene, addresses the stage designers of the period as follows : "I would tell you of the superb costumes of certain shepherds made of rich cloth of gold and of silk, lined with the finest of wild animal furs. I would also tell of certain fishermen whose dresses were not less rich than the others, whose nets were of fine golden thread, and of all their other implements, all of them gilded. I would tell of some shepherdesses and nymphs, whose robes were made regardless of cost. But I leave it to the intelli gence of the judicious architects to do such things when they shall find the patrons who are agree able to their wishes and who give them full power with generous hands, to execute all which they desire." Court Performances. — As the financial control of the drama passed from ecclesiastical hands into those of the princes, it was used more and more as an aggrandizement of the courts.

The costuming and mounting of the plays became more and more elaborate, one monarch trying to outdo the other in the splendour of the entertainments offered.

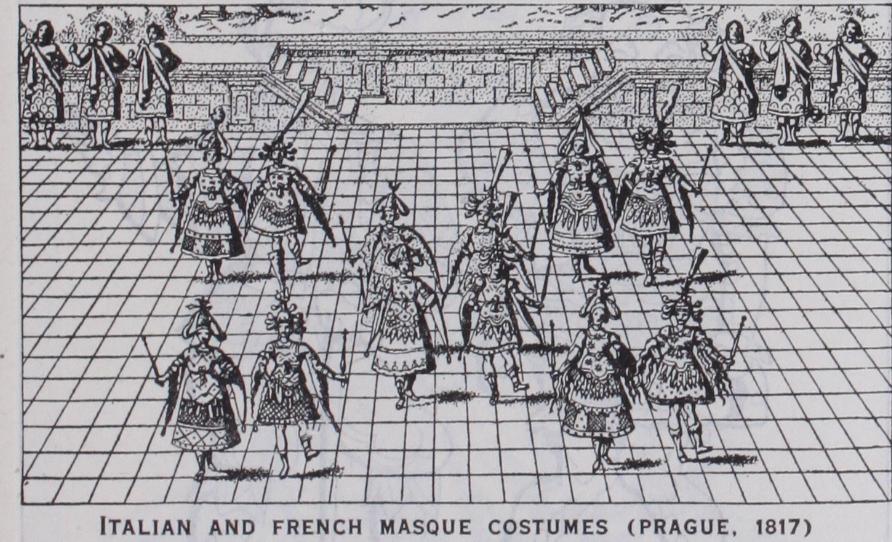

Marriages, coronations, the birth of heirs to the throne, even funerals were made an excuse for great display of costumes and pageantry. The Cities were re quired to give great feasts when the monarchs of the realm visited them. On the temporary stages erected for such occasions, tableaux vivants were posed in costumes rich in symbolic devices and emblems. Practically all the well-known painters, such as Albrecht Diircr, Velazquez, Rubens, Van Dyck, designed costumes and paraphernalia for entertainments of this kind during the i6th and early 7th centuries. In these tableaux the clothing of some of the characters was reduced to almost nothing, a fact which caused as much alarm among the reformers of those days as it had done during Roman times. Whether it is due to the number of engravings which have been preserved or not, Antwerp seems to have been one of the cities where the most elaborate of these entrance festivities were given, among them those of Philip II. in of the Archduke Ernest in 1594, and of Albert and Isabella in 1602.

The Flemish rhetoric drama was costumed in a Dutch version of the Italian classical period, and so were the court entertain ments in England. Inigo Jones, who together with Ben Jonson produced several masques, studied in Italy, and followed the Italian fashion rather closely. A few drawings of his are preserved at Oxford, among them some of the very few drawings of cos tumes of characters in Shakespeare's plays. In some of the productions in the London theatres of the early 1 7th century the costumes were probably imitations on a more modest scale of those worn in the court productions. In others the costumes, judging by some woodcuts which have come down to us, were like the everyday dress. Ben Jonson thus describes the costumes in the masque of queens : "The habits had in them the excellency of all devices and riches and were worthily varied by his inven tion," i.e., Inigo Jones's invention.

There was a regular stock of legendary characters which were costumed so that they would be easily recognized by the public : virtues and vices ; curiosity covered with eyes ; error with serpents and snakes ; credulity with ears. There was the earth with oak leaves, plants and flowers. There was water with dolphins and fishes, and the air with eagles and other birds. There was fire with fiery salamanders between the flames, and there were signs of the zodiac, the winds, nymphs, dryads and witches, all in their proper symbolic costumes. These masques and other court enter tainments later on developed into the court opera. Of the cos tumes of the intervening period we get probably a good idea from the floral costume in the painting by Rembrandt, which is similar to the costumes in several other paintings by men of the period.

Opera and Comedy.

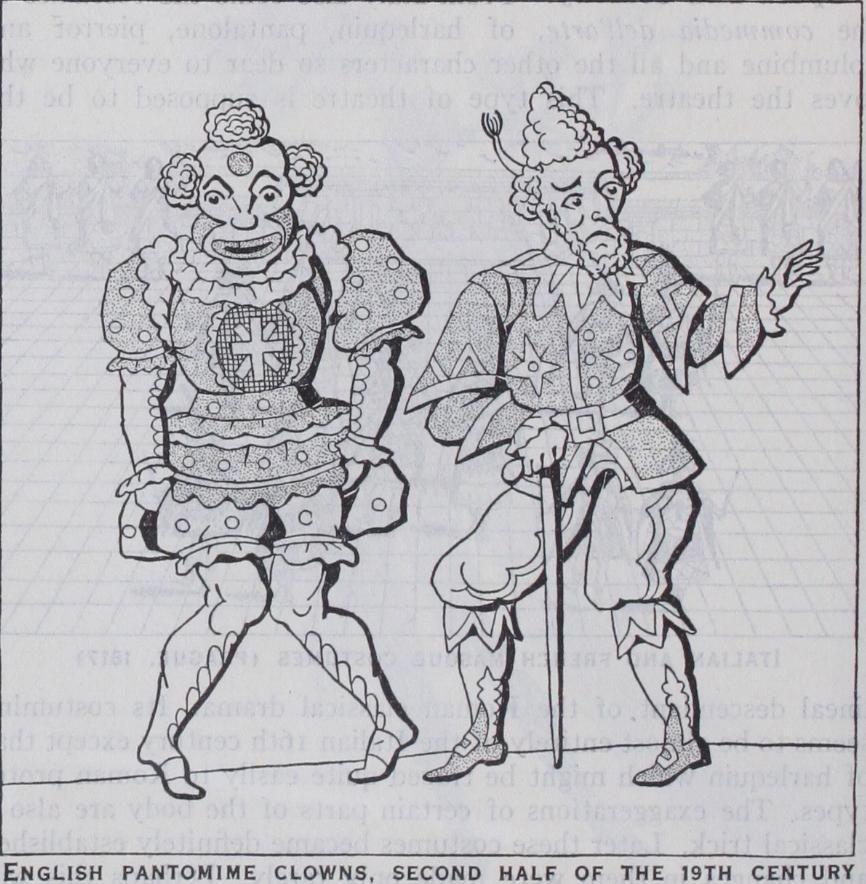

Frcm Italy also come the costumes of the commedia dell'arte, of harlequin, pantalone, pierrot and columbine and all the other characters so dear to everyone who loves the theatre. This type of theatre is supposed to be the lineal descendant of the Roman classical drama. Its costuming seems to be almost entirely of the Italian i6th century except that of harlequin which might be traced quite easily to Roman proto types. The exaggerations of certain parts of the body are also a classical trick. Later these costumes became definitely established and changes in them were made only rarely. Perhaps this was due to the method of production used in the commedia dell'arte, which only makes use of a certain number of characters, who reappear in all the different scenarios. In the course of the years new characters appeared, but on the whole the Italian comedy changed no more than harlequin's costume.

Poorly as the Shakespearian period is represented by docu mentary material, the opera is elaborately recorded. As a court entertainment, it received all the attention usually given to the exploits of the princes of the i6th and 1 7th centuries, to their ballets, their carousals, their tournaments and other dramatic enterprises. With the growing preponderance of France in European politics one may trace the growing aesthetic influence of France. As at first Italy influenced France in the drama as well as the other arts, so France now began to influence Italy. When designers such as Berain and Le Pautre originated a new set of costumes for a court entertainment, echoes could be heard all over Europe. As the masque was supplanted by the opera the costume gradually changed, the lines becoming more and more like the exaggerated court dress of the period.

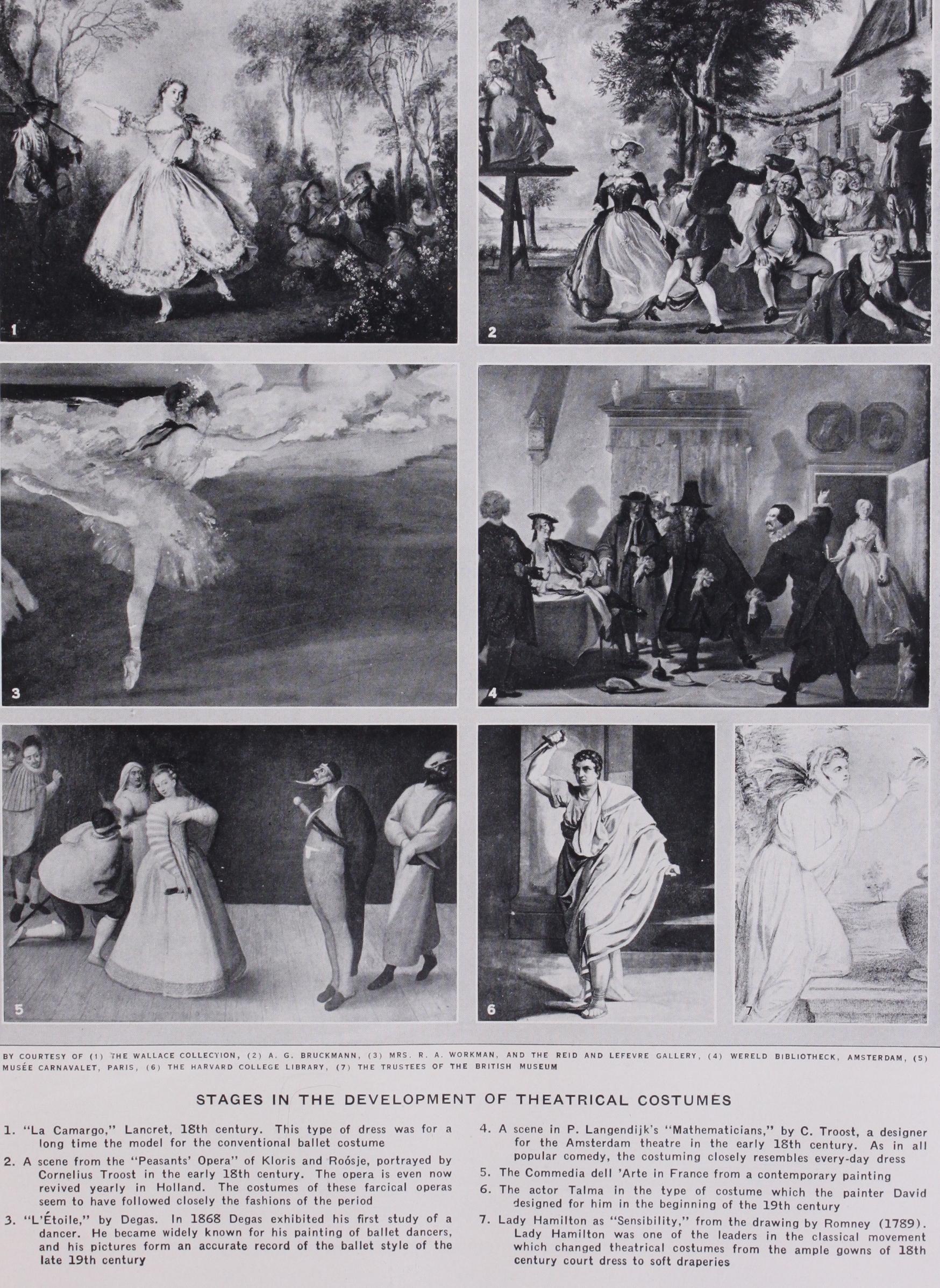

Entirely different was the costuming of the comedy stage which usually was of a realistic nature with a sprinkling of commedia dell'arte motives. The comedy often employed music, and sometimes comedies were made as skits on the operatic stage, called by such names as Peasant's Opera, the famous Dutch Kloris and Roosje, or Beggar's Opera, Gay's famous English enter tainment, both of the early 18th century. The costuming of these farcical operas, in fact of all comedy of that time, seems to follow rather closely the fashions of the period. Of course, fantastic plays called for a different kind of costumes and pre sumably followed the court performers in the same way as the popular Japanese theatre in certain plays follows the No theatre precedents, using more showy material and designs but adhering closely to the original type.

Modern Design.

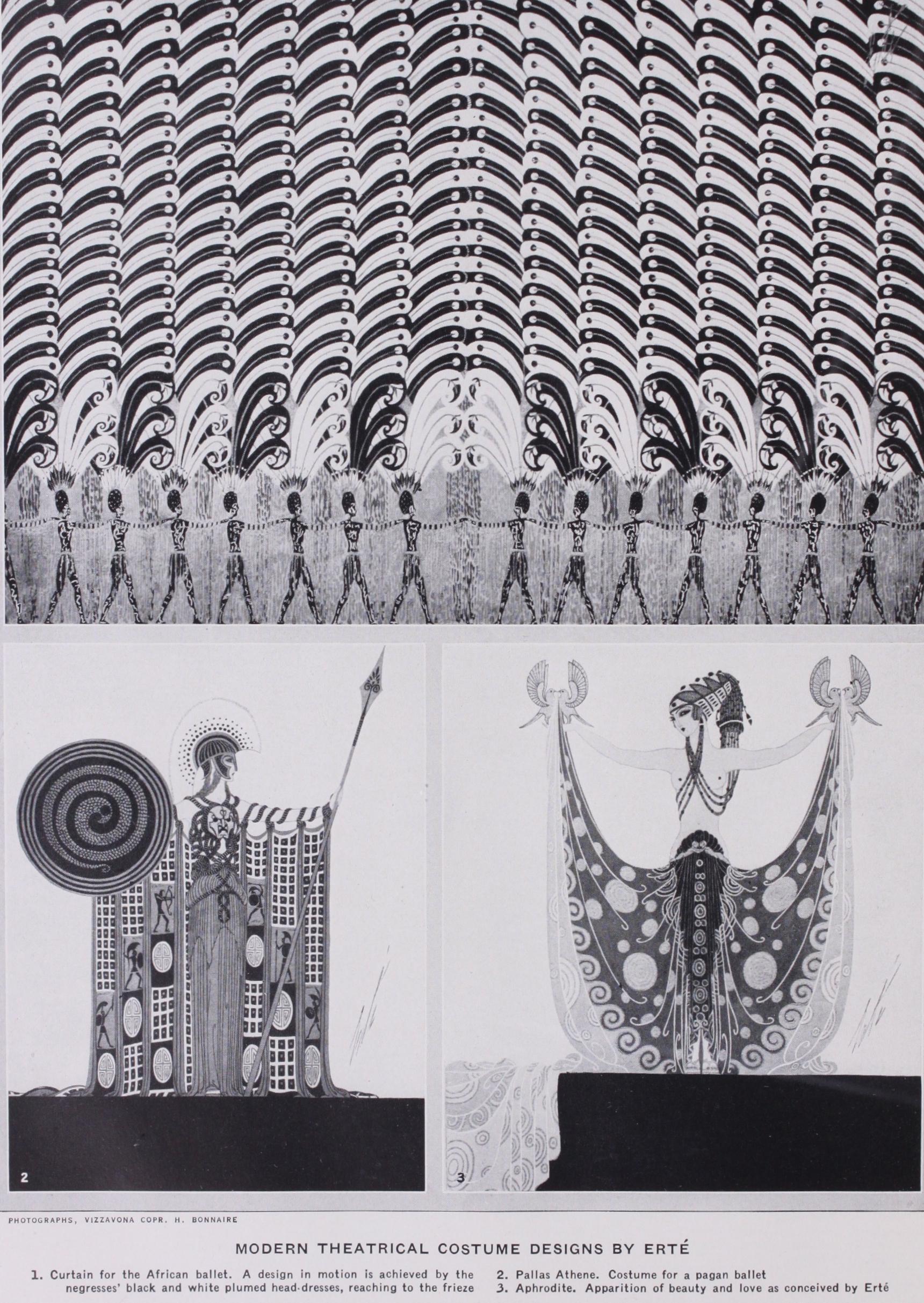

Towards the end of the i8th century the classical movement began in the theatre and within a few years the stage costume changed from the ample gowns of the i8th century court dresses to draperies of soft woollens and clinging gauzes. The Viganos, in their ballets, adapted subjects like Diana and Endymion, and used for the portrayal of these characters dresses of the lightest and most transparent materials. Some years earlier Lady Hamilton had given performances in classical drap eries only. With the advent of the romantic movement, the costumes which became the fashion were stage adaptations of period costumes. After the romantic Gothic revival one period after another seems to have come to the fore. The Gothic cos tumes of 184o, however, are entirely different from the Gothic costumes of the '8os. In each period only those parts of the original dresses were adapted which were not too incompatible with contemporary taste in form and colour. The modern dress designer for the stage has gone so far as to imitate the technique of pottery, sculpture, engraving and painting. Several modern designers also use old fashions as a source of motives, using them perhaps with a little more freedom than the original designers.From the time when Henry Irving ployed artists of fame to design the tumes and scenery for some of his ductions there has been a strong tion among managers, one trying to outdo the other in the artistic excellence of the costuming of the plays which he produces. Of course, the results vary enormously. The famous Meiniger troupe prided selves on the historical accuracy of their costumes. Men of the type of Tadema combine historical accuracy with a definite attempt to secure artistic mony. Others, like the Russian Bakst, sacrifice historical accuracy to the artistic conception, being chiefly concerned with the composition in colour, form and line. Attempts have been made to reduce the actor to a two dimensional figure by means of lighting, and even to annihilate him, as far as his value in the composition is cerned, and use him as an intelligent chine, animating the abstract composition of colour and form which he carries by way of dress. It is curious to notice how one of the best known of the modern painters, Paeblo Picasso, resorts to the same methods which were used by the i6th and 17th century designers in their emblematic costumes. The only difference lies in the artistic approach to the emblems combined to form the costume.

Technically, there are a few points in the construction of theatrical costumes which make them entirely different from or dinary everyday dress. First, the artistic meaning of the costume is usually exploited at the expense of any adherence to fashion. In the ordinary drama, where motions of the actors are not different from those of everyday life, the differences in construc tion usually limit themselves to simplicity in fastening and the choice of the materials, which are selected to appear well under the stage lights and from a distance. In costumes designed for dancers, acrobats, etc., the method of construction becomes of su preme importance to the artistic conception of the costumes. A ballet dancer can use skirts only of a certain length, an acro bat will have to protect certain parts of his body, others he must leave uncovered for the sake of free motion. It is probably on ac count of this difficulty of making the costumes of special artists of this kind artistically important that the managers have developed the expedient of the show girl, these girls being selected entirely for their good looks and their ability to wear and display elaborate stage costumes.

Materials.

The materials employed in the construction of stage costumes are often the same as those used for conventional dress, but usually the extremes in brilliancy are popular with the designer as this brilliancy is the only means by which he can avail himself of tonal and also of colour value. Of ten substitutes for expensive materials can be used which give an equally elaborate effect and are equally serviceable. The distance at which the costumes are usually seen not only makes these changes possible but sometimes even makes them necessary. This is especially true of all materials which are decorated with patterns or have been embroidered, for it is much easier to get an effect with the painted or appliqued metal sur faces in an imitation brocade than it would be to get a similar effect out of a woven fabric. Some painters treat their costumes as if they were a part of the stage scenery, and by using mat sur faces only, produce a certain paint-like quality even in the dresses. The materials most com monly used for indicating more costly fabric are muslin, satin, cambric, cotton, flannel, terry cloth, oilcloth and the like. In Goethe's day glazed chintzes seem to have been a common substitute for silks, he himself ad vertising the use of them. In the middle ages a great deal of use was made of printed linens brightened with gold. Among the Javanese extensive use is made of the batik technique which has also found favour with a great many contemporary Western de signers. To-day, as at all times, applique work is very popular with costume designers as well as the more showy kinds of em broidery. In stage embroidery liberal use is made of small mirrors, spangles, braided straw, chenille and similar materials; curled ostrich feathers have always been a favourite material.The materials used for the making of masks have been leather, papier macho and wood, and for larger masks cloth stretched over a skeleton of bamboo, ratan or wire ; even leaves have been used. Most of the modern masks are made of papier macho over a base of modelling wax or plaster of Paris in much the same way as the commedia dell'arte masks were made from leather over a wooden mould. When a great number of the same masks are de sired the usual method is to reverse the process, the mask being made of papier macho inside a form, the resultant cast then being painted or lacquered in the same manner as the other masks are finished. The Japanese No masks and the Javanese topeng masks are made of lacquered wood ; the Chinese and Tibetan masks are made of papier macho, which material the Chinese use for the construction of entire costumes, making the actors resemble lacquered statuary, as for instance in the case of the Kwan Yin costume now in the Field museum in Chicago.

Legal Regulation.

From time to time ordinances have been passed to regulate theatrical costuming, but they have usually failed. During the i8th century a certain conformance with local custom was considered necessary by the management of the theatre, and the actors and actresses were instructed to dress according to the rules of etiquette. Actresses who portrayed ladies could not wear simple short-waisted dresses but had to wear at least demi-parure, or if several ladies took part in the scene they were to wear grande parure and no hats. Soubrettes were to wear no hats except when travelling, and no rings ; only simple dresses possibly of appliqued atlas. Young girls of the bourgeoisie were to wear skirts and jackets but never made of white material, at least never when the first lady was wearing white. The Jav anese, Chinese and Japanese costumes are also stringently regu lated, but even if regulations were not made, common sense would reach the same results. Who for instance would attract attention to one of the minor characters by dressing him in a vivid colour at the expense of more important players in the same scene? The dimensions of the human body and the motions which are natural to it have, of course, determined the form of costumes more than any other factor. Costumes peculiar to cer tain types of actors seem to persist through the centuries, and if these traditional forms are changed by intense artistic endeavour or even by political ordinances from time to time, they will pres ently reappear. The English Christmas pantomime costumes of clowns and harlequins are not different from the costumes used by the artists in the commedia dell'arte or even by the comedian who acted in the Greek and Roman farces. What determines the form of a costume most is the actor and his work. If certain motions which the actor is to make look best when made in certain costumes, these costumes will naturally persist.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.--C.

F. Floegel and F. W. Eberling, Geschichte des Bibliography.--C. F. Floegel and F. W. Eberling, Geschichte des Grotesk Komischen (1862) ; C. Mantzius, A History of Theatrical Art (6 vols., 1903-2I) ; G. Groslier, Danseuses Cambodgiennes (1913) ; M. C. Stopes, Plays of Old Japan, the No (1913, end ed., 1927) ; E. Stern and H. Herald, Reinhardt and Seine Biihne (1918) ; M. Bieber, Die Denkmdler zum Theaterwesen in Altertum (192o) ; C. Niessen, Das moderne Biihnenbild (1924) ; K. MacGowan and H. Rosse, Masks and Demons (1924) ; L. Barton, Historic Costume for the Stage O. Messel, Stage Designs and Costumes (1933) ; I. Monro, Costume Index (1937) ; H. Hiler, Bibliog. of Costume (1939). (H. Ro.) There are various ways of regarding costumes in the theatre. Costumes may be a realistic period clothing for the actors, in which case they are of little interest beyond being an example of historical data. They may be an elaborate and ornate fantasy, designed purely for the purpose of pleasing the eye and forming a picture, sometimes actually derived and adapted from paintings and sculptures of certain schools. Costumes may however play a far more important part in the theatrical production : namely as a psychological study of the characters individually and of the spectacle as a whole. It is this third, or what might be termed the more modern, development of this art that is of greater impor tance in the theatre to-day and therefore requires more consider ation than is usually given it. A progress of this kind may pos sibly, at some future date, result in a uniform for actors, differing one from the other only in colour pattern to show the status or relative value of the figures clad.Artists are always searching for the new, striving step by step for what they think is right, toward an ultimate goal of self expression and interpretation. In the theatre, the furthest point so far reached is a stylization of individuality ranging from design to the actual material used in the execution of the clothes. There is one great hindrance to an actual and far-reaching progress in designing for the theatre of to-day. It is the paucity of theatrical productions which give the artist sufficient scope for creation.

The stage reached the climax of a glamorous and overdecorated period in 1914. That was the height of a certain baroque style in the theatre. It was unnecessary to go any further along those lines, anything of the same type that came later could only be compared with or be an exaggeration of the original. It was an easy form of spectacle to understand and tremendously effective.

"The play's the thing." Next should come the regisseur; the actor third and the decoration last. The decoration should be completely under the direction of the regisseur, who should guide the entire production, not merely direct a play and, which is worse, direct it badly, as is so often the case, but actually lead the performance like the conductor of an orchestra. He should always be a man of authority, culture and taste, combining all the arts: as such he would create a fine production. Nothing should be done without his word. A director of actors should be under his guid ance, since it is not necessary for the regisseur himself to direct their every move ; except for giving the final touches.

This manner of directing, which is not by any means new, is the only possible road toward a truly fine result. The regisseur should always bear in mind the relative values as given above: if one of the branches oversteps its own importance, there is the danger of the entire production being overbalanced. If the scen ery, for example, is too ornate, it will of necessity interfere with the visual background of the actor. If the costumer loads down his poor patients beneath head-dresses and bejewelled clothes of impossible sizes and weight, the acting will suffer accordingly.

Importance of Simplicity.

An actor should be clothed as simply yet as appropriately in colour, texture and design as neces sary. The costumes of the principal actors should be an asset to them, a help, an interpreter of their character, an aid in their movements; they should free them in order that the artists may give all that is in their power without being hampered in any way. Moreover a player acting an important part should be in com plete contrast to the background, so that his motions always appear clear and well defined. Supposing, as a rather crude example, that the scenery is black, the leading actor or actress should be in white. The people of intermediary classification of parts would be clothed in the corresponding scale of colour accord ing to their importance, the quite unimportant characters finally going so far as to melt into the background and actually become part of the decoration.This theory was realized with great success in Reinhardt's per formance of King Lear in Vienna, when at regular intervals across the backdrop of a huge but perfectly simple grey wall stood knights in dull silver armour, on pedestals, leaning on their tre mendous shields and thus forming decorative pilasters. Even in that instance there was colour only in the pattern (coat-of-arms) on their shields. Their silver armour blended into the silvery walls, resulting in a suggestion rather than in a reality, which never interfered with the action. In fact, costumes should never over-attract attention; they should pass utterly unnoticed, if they are to be right. The same should be the case with scenery. No matter what the decorative scheme may be, the setting should always come second to the costumes, be of relative value and of the necessary simplicity to form an adequate background for them and therefore naturally for the artists wearing them. What is worse than to go to see a favourite artist play a famous part and not be able to see the face or body, for the lack of lighting, or on account of the brilliance of the costuming, or, worse than every thing, because of a background which is so crowded with pattern and design that one cannot concentrate on anything else? At the Theatre Francais the superb acting of a well-known star was actually invisible owing to an over brilliantly lighted crystal chan delier which hung in the middle of the stage and drew all the attention, though of absolutely no interest or import to the plot.

One should revert to the "Primitive" idea of staging, as in the other arts, to attain the greatest beauty. Just as those six sta tionary knights in King Lear denoted the castle, a garden for instance would be represented by a tree of a decorative design if a general impression only is wanted, or a tree of a particular kind, to suggest the garden's geographical situation; e.g., a palm tree would suggest Africa, a stone pine southern Italy, a cypress Tus cany, an elm New England, and so forth. Moreover unless the tree literally plays a part in the production (in other words, unless it becomes an "actor") it should be merely suggested, in outline or in tone; it should never be realistic. If a tree is called for in the plot and is vital to the action, it might be represented by a human being, in order to give the necessary movement and play of nature, the wafting to and fro, the trembling and bending by the wind.

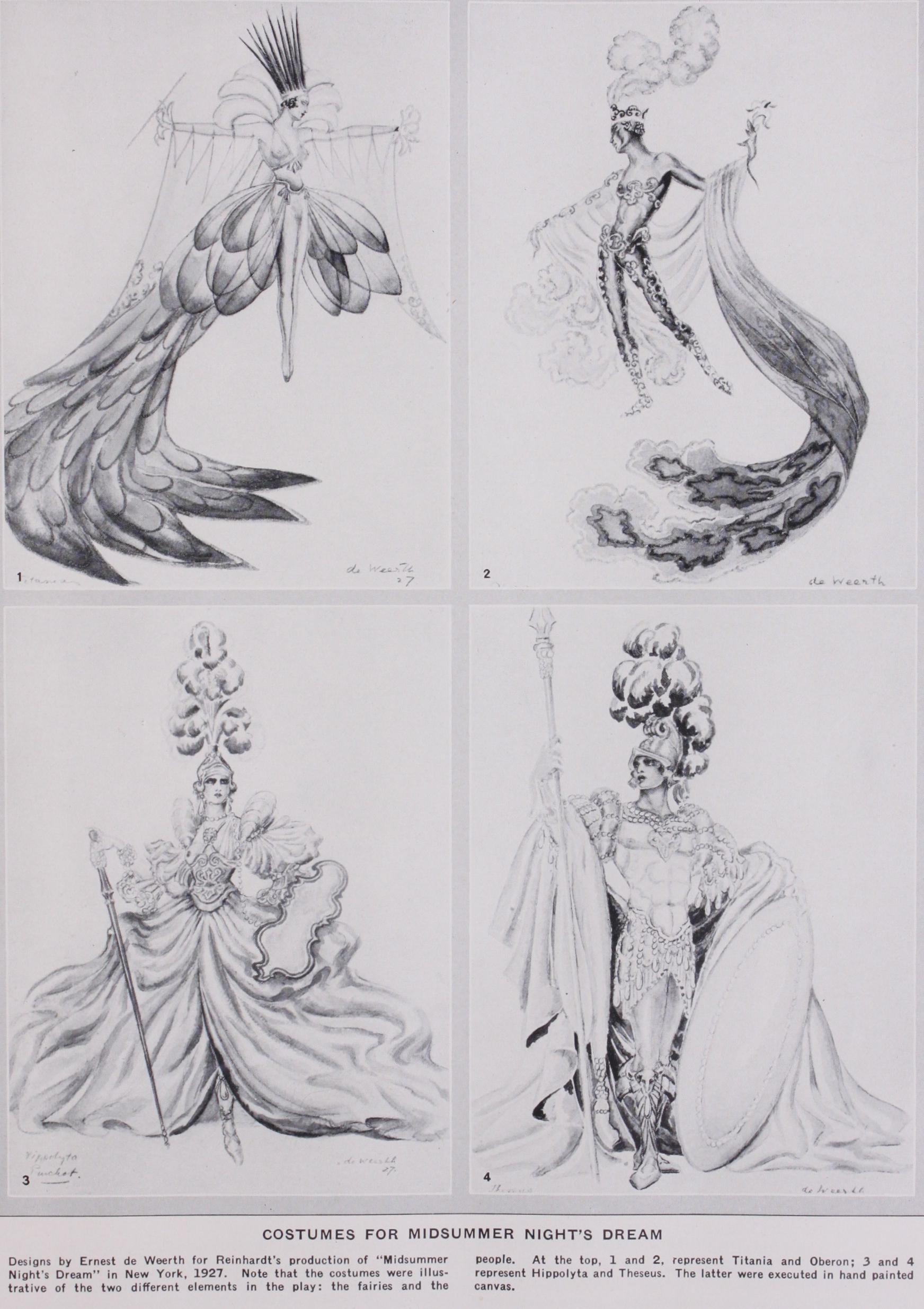

The stage should be alive. Only the things which really matter and are of importance to the plot and action should be shown; the rest left to the imagination. Everything actual should play its part. Macbeth, Hamlet, Lear, Medea, Oedipus, or Electra are all plays of a cosmic nature, possible to interpret in a hundred different ways. Thus Reinhardt alone has staged A Midsummer Night's Dream in something like 15 various styles. His original production was staged realistically. Another was done by Gran ville Barker with gilded fairies; yet another by Reinhardt in the manner of Botticelli. In New York it has been given an r8th cen tury setting like a fresco by the Venetian Tiepolo. In order to render the full effect of his style, the costumes were actually made out of painted canvas, but there were no actual designs or patterns on them. The folds were accentuated with high lights and shad ows ; otherwise there was no detail whatsoever which would attract unnecessary attention.

Use of Rubber.

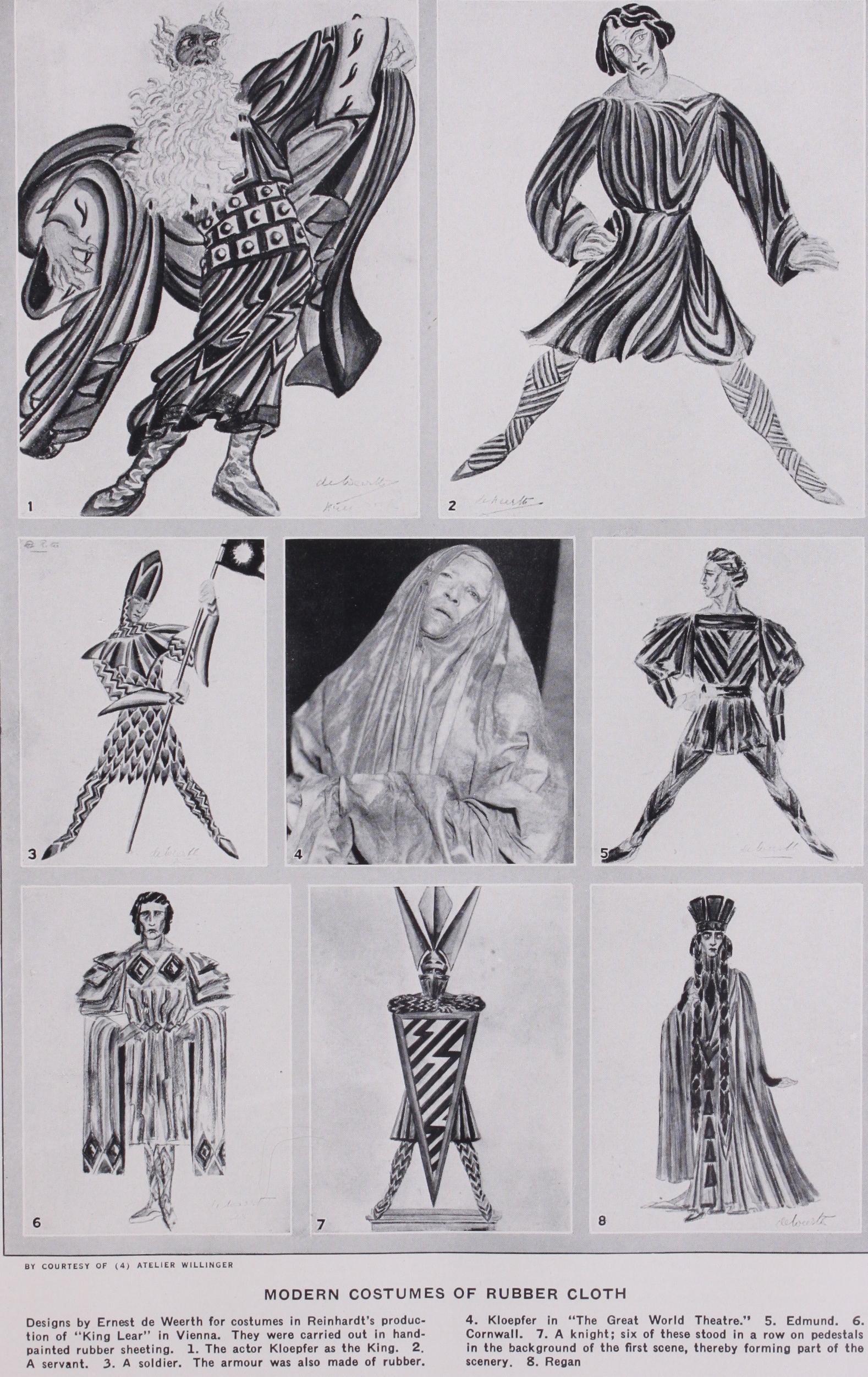

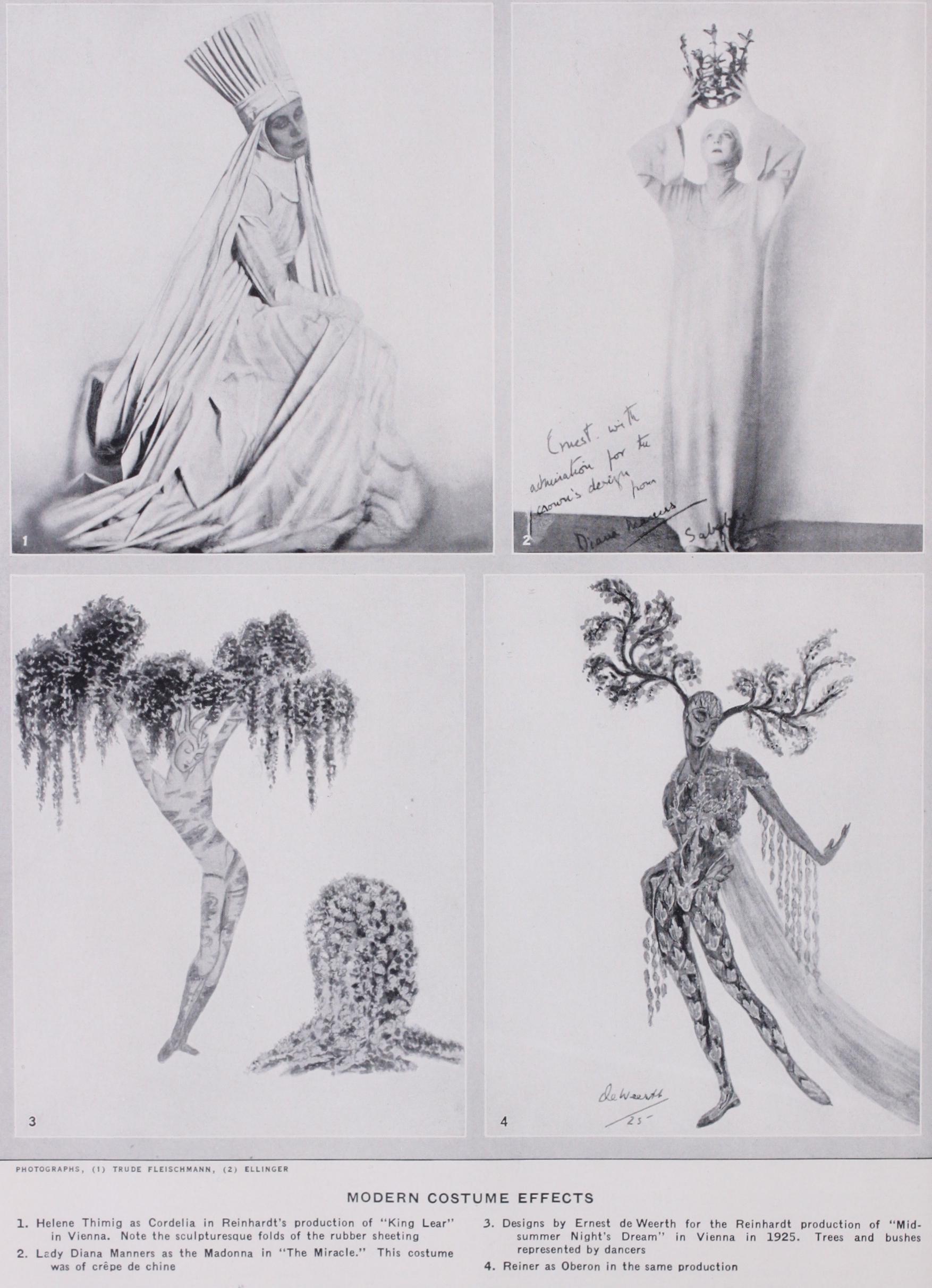

One of the most extraordinary instances of successful designing was in Reinhardt's production of King Lear in Vienna. The costumes were made of rubber sheeting. On the opening night the unusual use of this material passed unnoticed save that the critics praised the beauty of the performance as a whole. A few days later the rubber was a sensation. The reason for using that material was that Reinhardt wished the characters in Lear to look as though they had been sculptured out of stone. This was not in itself a new idea. It had been done with the figure of the Madonna in The Miracle in New York. In this particular instance however when the statue came to life the actress was obliged to step forth out of her cement robe, rather like a chicken breaking through an egg shell. The mantle was made out of some rigid and stiff preparation which would of course have been quite unsatisfactory for an entire cast of actors. Oilcloth was rejected as an impossible medium, being paperlike and clumsy. Rubber sheeting was chosen. It was found that when stationary it falls in magnificent and completely sculpturesque folds, and when in motion it is altogether supple and moves with an easy grace that clings to and follows every movement of the actor. It was painted in tones of greys, terracotta, pastel blues and mauves, mixed with silver and gold which gave it the glimmer and vitality of stone. The result was amazing.This material was also used in Salzburg in von Hofmannsthal's The Great World Theatre, when by slightly different weight and treatment it successfully represented painted wooden figures. The scene was a vast and towering church altar in three stages, one above the other, connected by invisible steps and inclines. On the lower level were niches wherein stood the allegorical figures of Beauty, Wisdom, Wealth, etc. These were dressed in brilliant colours. Above them stood Holy People in variously toned shades of copper, brass and steel. At the top, rising to a summit in the centre, were the angels, all in armour, one mass of glittering gold and silver. The rubber when painted with metal pigments takes on a shiny and resplendent quality which is unequalled in any other material. Furthermore, in order to keep a consistency throughout the scene, even the Beggar, in his torn and drab rags, was clothed in rubber; it may appear like old moth-eaten cloth carved out of wood when so desired. The stained-glass window effect which was produced when the various coloured lights were turned on the upper figures covered with the shiny metal rubber was an unforgettable impression ; so successful indeed that Rein hardt used this idea again in New York for the angels in the final tableau of Jedermann (Every man). In this instance they were not clad in armour but in the flowing golden folds of early Gothic statues. They wore no tinsel haloes, but wigs of little gilded curls, also made of rubber.

A very important factor in costumes of unusual material hand painted to resemble carved wooden images, statues of marble and metal, etc., is the "make-up" of the people wearing them. This can be no ordinary stage grease paint with rouge and mascara. The "mask" must suit the costume, look just as wooden as a fig ure carved from oak, as stony as a statue sculptured out of marble; and still be the movable face and skin itself, capable of every expression and pantomime. In shadows and high lights it should follow the lines of the clothes, in colour equal their intensity, tones and shades. This naturally applies to wigs and head-dresses as well. In King Lear, for example, certain of the actors volun teered to make up their own hair without being obliged to wear wigs. This meant actually painting lights and shadows in colours and metal. This would of course be impossible anywhere but in a theatre where plays are given on the repertory system. One could hardly expect the actors to make up in this manner twice in one day as is the custom where plays are put on for "runs." The result, however, starting as it did from the normal and actual nature of hair, was even finer and more successful than the com pletely stylized quality of a wig. The women in Lear and The Great World Theatre wore head-dresses which concealed the hair, with the exception of tresses long or looped up, which were made of lightly padded, woven and plaited rubber. Cordelia in King Lear was completely shrouded in a pleated nun-like veil of the same material so that no hair was visible. For her costume white rubber sheeting was used, painted in grey with shadows of jade green and pastel blue, which gave her the pallor and transparency of ice, like the Madonna in a certain famous Crucifixion where she seems frozen to stone in the agony of her suffering. The evil sisters, on the other hand, were clothed in colours of moss-covered rocks and topaz, green and brown, yellow and orange. In spite of the many different tones, the general scheme of the entire produc tion was grey, as though carved out of stone, with the lights giv ing the variety. Each individual had his or her own scale of col our : the King himself wore gold and purple combined with a replica of ermine, but the manner was always subtle, merely a suggestion. That is what is meant by a psychological study of the characters individually and of the spectacle as a whole.

Rubber must not be judged as an invention, nor as a criterion for new costuming. In these productions it merely served a pur pose and may be used in various other ways, not only for entire costumes. Jewellery has been made of it ; the reason being that any sparkling stones attract too much attention to themselves and therefore interfere with the consistency of the stage picture. One of the many interesting advantages of using rubber is that its brilliancy may be regulated according to the necessity. Helmets, spears, armour in general, may be made shiny or dull at will by merely adding gold or silver paint and polishing or painting over. Even soldiers' plate-armour has been made of little circular scales of rubber superimposed and painted steel colour and blue, the edge of each flecked with silver. The helmets, built on a buckram form, were covered entirely with the rubber sheeting, the high lights painted in polished silver, thereby giving an effect of shiny steel without the dazzling and disturbing reflection of real armour. This method enables an actor's face to be at all times clear and visible.

In Kwan Yin, a Chinese opera performed in New York, rubber was used as a decoration on the costumes. The excessively ornate clothes of the Chinese actors have as a rule a tinsel quality, which to Westerners is a trifle vulgar and certainly foreign to the new tendency toward simplicity in our theatres. Therefore the designs, instead of being embroidered with metal threads and sequins were painted on a comparatively inexpensive material. The heavily embossed parts and the thick, rolled edges were executed in rubber stuffed with cotton batting and painted with metal pigments, pol ished or left dull according to the result desired. Even the little mirrors so often used on Chinese costumes could be faithfully reproduced without giving the disturbing sparkle. The result was more like•a Chinese painting of a drama than an actual Chinese theatre.

It must be remembered that the stage is always extremely de ceiving, tricky and utterly unrealistic. The most exquisite and magnificent brocade may lose every vestige of its value once it is seen "across the footlights"; and it is also very costly to acquire. On the other hand, a piece of cheesecloth, treated and painted in the right manner, may look like the finest tissue from Tyre. Cloth of gold may look dark and drab, gilded rubber worth a king's ran som. The point is to find what material, combined with treatment and paint, will give the best result.

Often strong contrasts are desired. This is only attainable by means of a great variety in the stuffs used. In order to give the feeling of the storm in King Lear, Reinhardt wished to have a con tinual movement on the stage throughout the heath-scenes, though the simple grey-blue cyclorama and the lack of any realism on the stage in the way of trees or rocks, proved a difficult problem for the designer. True, there were moving clouds and other light effects, sounds of wind and rain, the roaring of thunder and vivid flashes of lightning; but yet not enough movement. Veils were used, of every conceivable thickness, size and weight ; not, how ever, as scenery. They were worn as costumes, carried, wafted to and fro, dragged across the stage by girls, who themselves were shrouded in these mists of blues and greys, with streaks of silver painted on them to catch the light as they passed, tearing across the back like ragged bits of fog driven hither and thither by the storm. The contrast of these light and airy muslin veils with the heavy rubber folds of the stonelike figures of the actors can well be imagined. Lear stood like a monument hewn out of rock, braving the elements.

Reinhardt's "Midsummer Night's Dream..

In Reinhardt's production of A Midsummer Night's Dream in the Tiepolo man ner, the costumes were made out of canvas, in order to resemble as closely as possible the actual paintings of an old master. There was, however, another and possibly more important reason for employing the material. In this comedy of Shakespeare's there are two strongly opposed factors : on the one side, the human being of Theseus' court and on the other, Nature, as represented by the forest and the Fairies. Puck is the meeting point of the two. The whole has a dreamlike quality and therefore even the human beings may be costumed as fantastically and imaginatively as be comes entertaining. Moreover, to many people the play has a rather childish mood and certainly the classic Greek attire is wearisome at best. Accordingly, the i8th century interpretation of mythological characters was selected, which gave Theseus and Hippolyta waving plumes and tremendous robes of heavy silks and satins, and the other members of the palace rich and ornate brocades. In order to produce this effect and further accentuate the stiffness of the Court, with all its pomp and forced rigidity, nothing could have been as satisfactorily hard and unbending as thick painters' canvas. Not even the plumes could be made of feathers, because they would have been too realistic. They were therefore made of thick muslin, gathered and drawn close on wires, and then painted and sprayed to look like feathers sketched by a master technician.The result of those Court scenes was truly magnificent. There was no actual scenery. The backdrop was designed as two gigantic tapestries surrounding the stage in a semicircle. The main opening was in the centre. For the fairy forest scenes, these curtains could be lighted from the back and became translucent. An elevation in the centre of the stage consisted of inclines running in circles to different points and altitudes and leading to exits above and below the stage level. At the same time, this entire structure was joined together in the middle by one long flight of steps, down which the wedding procession came in the last scene. The figures looked as though they might be stepping forth out of the very tapestries, so unreal and exotic did they seem. Around the back of the stage to the top of the staircase on either side stood living candelabra: people clothed in armour wrought in wondrous shapes of "gold and precious stones" and holding a thousand lights.

How airy and slight, exquisitely dainty and youthful seemed, by such a complete contrast, the springtime smilax, the fern-like veils and transparent muslins of the fairies. It was Nature unloosened in a moonlight night of fantasy, far removed from the rigour and severity of a bombastic court. The forest became the human element. Bushes moved and mists floated by. Through a fog, in a cloud of mystery, Oberon and Titania appeared like two white and radiant blossoms in the dusk. Their costumes, consist ing though they did of veils and gauzes, were in no way realistic copies of flowers. Rather were they, in design, of the very same i8th century period, both in shape and f orm. The important dif ference and complete contrast lay in the fact that they were executed in transparent silky veilings in contrast to the heavy canvas of the court costumes. When Titania lay asleep on the mound, a graceful silver birch watched over her from above, gently waving her tender and fragile arms with muslin leaves in the dream-like breeze of imagination. Later on, she beckoned to other silver birches to join her to gaze upon the strange spectacle of their queen making love to an ass's head; until at last the stage seemed full of youthful trees, a grove of birches shining silver in the night. Dawn appeared and dispersed the moonbeams; ferns, trees and bushes slowly vanished. The heavy rustling of the canvas robes, stiff and rigid, together with the metallic sound of trumpets and horns, ushered in the court once more.

Of such combinations and contrasts have Reinhardt's perform ances consisted; whether always successful in the carrying out of the ideas is of little or no importance. The chief reason for this elaboration of a production, which in fact simplifies it, is that it brings a play to life. Furthermore, it does not interfere with the acting. If Theseus and Hippolyta had been obliged to move about freely they would not have been clothed in stiff materials. As it is, the poet intended them merely to stand, look handsome and de claim. When the lovers fled to the woods, away from the pomp and dignity of the court, they, quite naturally, shed their stiff and cumbersome outer garments and head-dresses and were free to move, run, lie down, etc., in no way hampered by their clothes. Puck was in tights. Absolutely nothing interfered with his pranks, leaps, jumps, bounds and somersaults. He was painted from head to toe ; in front, in brilliant colours and gold to re semble the courtiers; on the back, in greens and silver to suggest the fairies. Thus when he turned about, he could become almost invisible by the colours of his back melting into the woodland scene. Puck is the actor in A Midsummer Night's Dream who requires the greatest freedom of movement ; therefore he could not have been impeded by any unnecessary materials and had to resort to his ingenuity of make-up to bring about the desired meet ing point between mortals and the realm of the unreal.

Shadow Costuming.

An interesting project for a music drama has long been under consideration, in which the characters on a lower stage would be the singers clad in rich and elaborate costumes. They would sing without acting, merely f orming a pic ture representing the period desired and set the mood. Upon an upper platform would be cast shadows, either from below against a solid background, or in silhouette through a translucent "drop." (Both of these might be used simultaneously.) These shadows, freed from decoration and merely clothed in tights, would play the scene which in song would be told about below. Their every movement would be visible and clear, undisturbed by hanging sleeves or trains; moreover, by arrangements of the lights and background, the figures on the upper level could be en larged or reduced according to importance or desire, resembling the "close-ups" in a cinematograph.Another possibility of this sort of shadow costuming would be to have the actors playing on a level above the mob and unim portant characters. Above and behind the principal actors would be cast the shadows of the people in their thoughts and imagina tion. As an example of this, Medea standing high above the Greek Chorus is plotting the death of her children. In shadow, above her, stripped of all earthly and unnecessary clothing, she sees her self in the act of killing them. Or, in other scenes, the chorus might be shown in shadows only, so as not to interfere with the concentration on the principal actors. At a climax, like Mark An tony's speech in Julius Caesar, the Roman mob could be just as realistic and seem far vaster in number, if only dimly seen in silhouette below the speaker. Antony would stand alone and impressive in the brilliancy of a central spotlight.

There are so very many ways and means of gaining truly won derful effects, even on our stages of to-day, and yet how often do we see the same old-fashioned scenes and costumes, lighted in the same conventional manner. The fact remains that design in cos tuming is not the most important part. It is invention, creation, flights of imagination and ideas, which denote progress in the art of staging. It is not necessary to go so far as to put people in wheels and ladders, pieces of machinery, motor horns and sheets of music. These may look like effective attempts at post-impres sionism and cubism when sketched on paper, but they are not and never can be an adequate clothing for actors, if we are to consider the theatre as an art centre for dramas in which the play and acting are the most important items.

For the most part, theatrical producers and even the public seem to imagine that designing costumes for a production means an artist drawing pretty sketches, usually in water colours, and hav ing dressmakers carry out the designs by matching the colours and trying to decipher what material was meant, whether velvet or Chinese silk or organdy ; pictures these, sometimes actual mas terpieces, records of old time periods which, framed and hung in museums, will go down to posterity. That is not progress in cos tuming. Just as there has been a slow but astounding change, dur ing this century, in the mechanism of the stage, scene shifting, theatre architecture and, above all, lighting, so there is also in cos tuming. What a startling difference there is between an old operatic production of La Gioconda dressed in the realistic cos tumes of velvets, paste jewellery and gilded lace, and Reinhardt's King Lear, clothed entirely in rubber. One was realism, the other art. Realism, the imitative portrayal of the real, without the inter mediary of poetry and genius, can at best only breed confusion, which excludes it from the realm of art. Lear is a product of genius with a dominant idea throughout ; so also in decor and cos tumes there should be a simplification of means, thereby directing the attention to the great purpose of the play. The highest mission of the theatre is to present creative ideas. The field is so new that unfortunately there have been few pioneers who have been equip ped with the necessary financial backing, combined with the cre ative instinct, to develop these new ideas in costuming.

(E. DE W.)