Botany and Cultivation a the Cotton Plant

BOTANY AND CULTIVATION A. THE COTTON PLANT Cotton consists of unicellular hairs which occur attached to the seeds of various species of plants of the genus Gossypium, belong ing to the Mallow family (Malvaceae) . Each fibre is formed by the outgrowth of a single epidermal cell of the testa or outer coat of the vessel. The derivation of the word cotton is from the French coton; Arabic qutun.

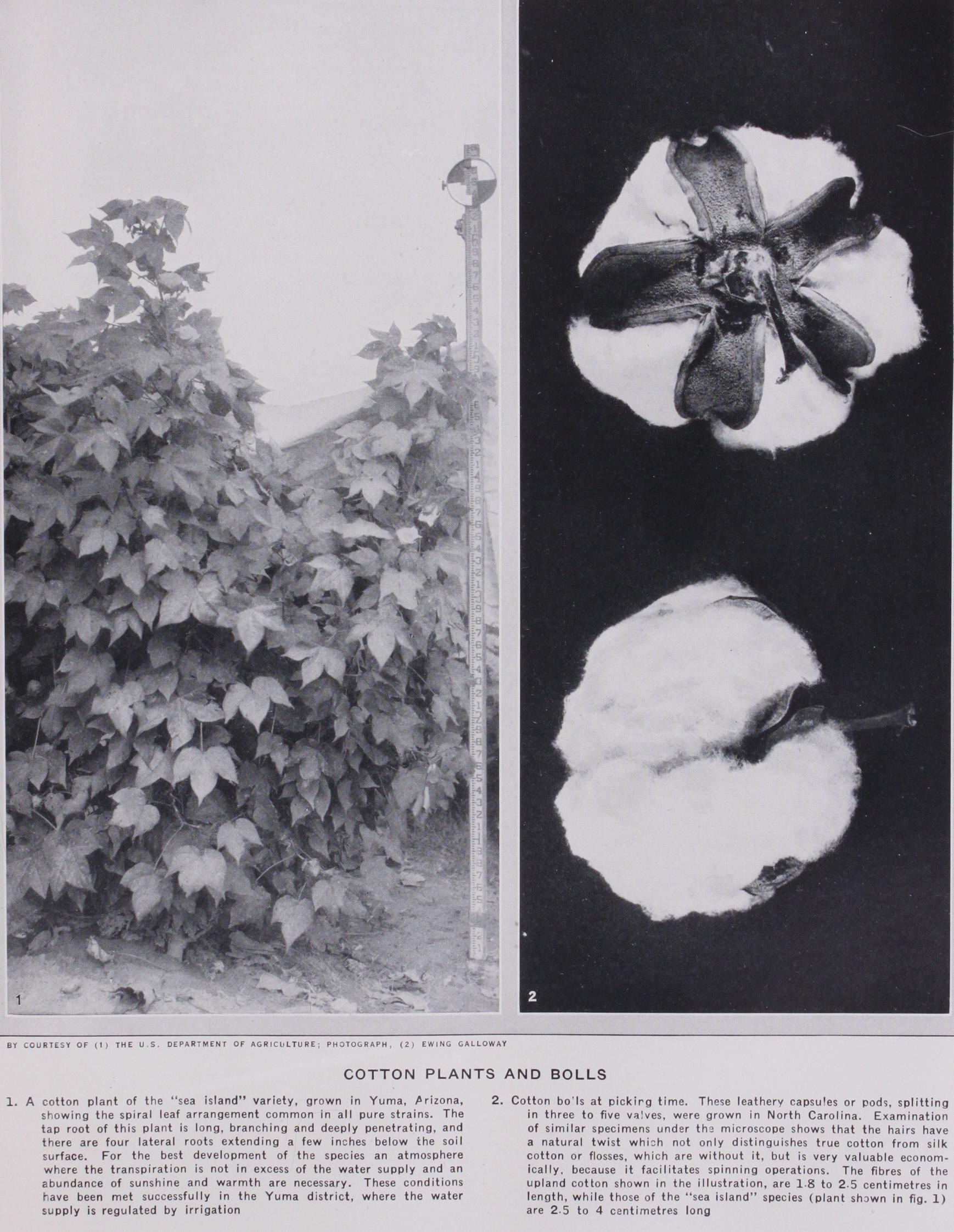

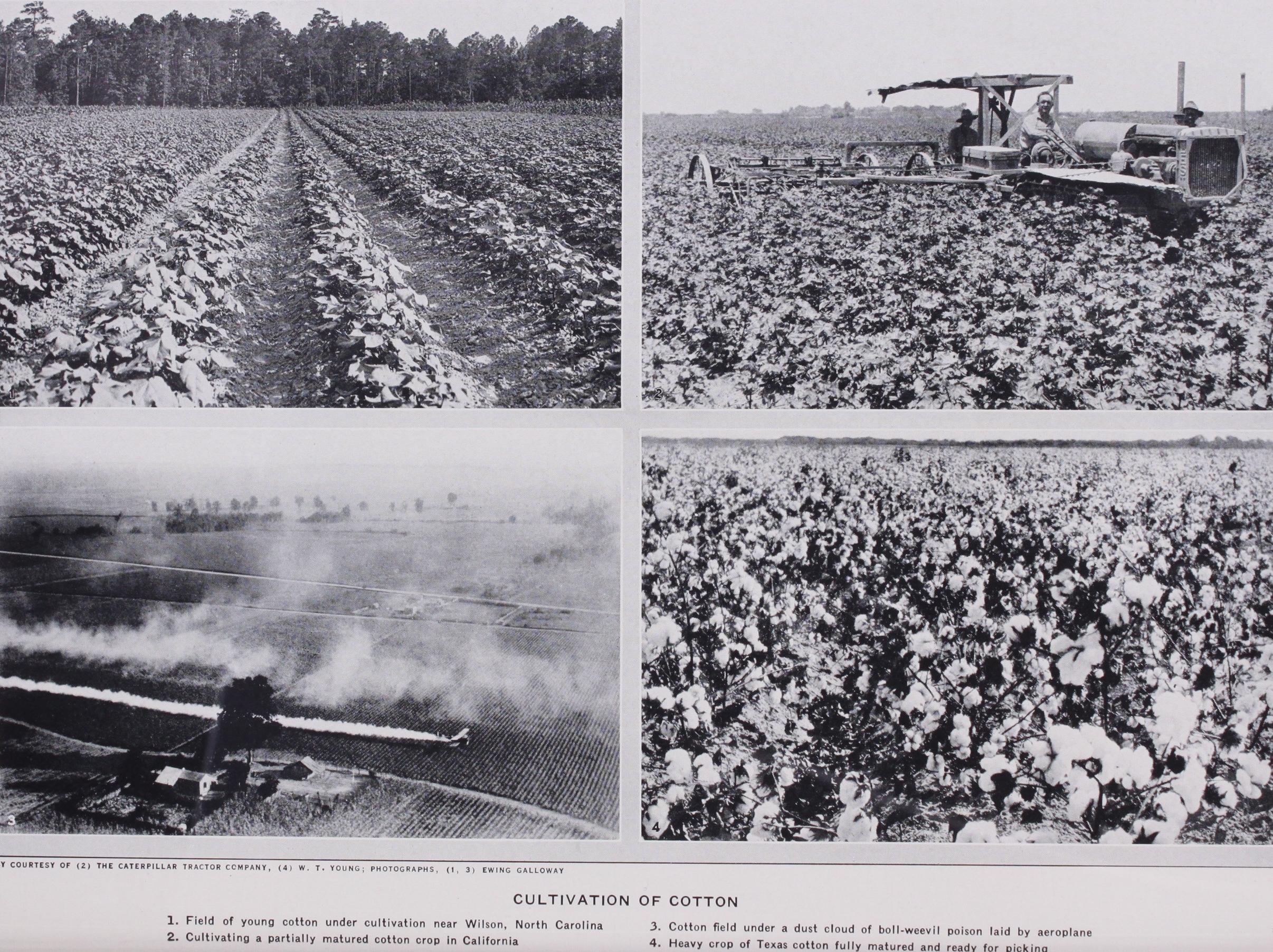

The genus Gossypium includes herbs and shrubs, which have been cultivated from time immemorial, and are now found widely distributed throughout the tropical and subtropical regions of both hemispheres. South America, the West Indies, tropical Africa and southern Asia are the homes of the various members, but the plants have been introduced with success into other lands, as is well indicated by the fact that although no species of Gossypium is native to the United States of America, that country now pro duces over two-thirds of the world's supply of cotton. Under normal conditions in warm climates all the species of cultivated cotton are perennials, but, in the United States for example, cli matic conditions necessitate the plants being renewed annually, and even in the Tropics it is often found advisable to treat them as annuals to ensure the production of cotton of the best quality, to facilitate cultural operations, and to keep insect and fungoid pests in check.

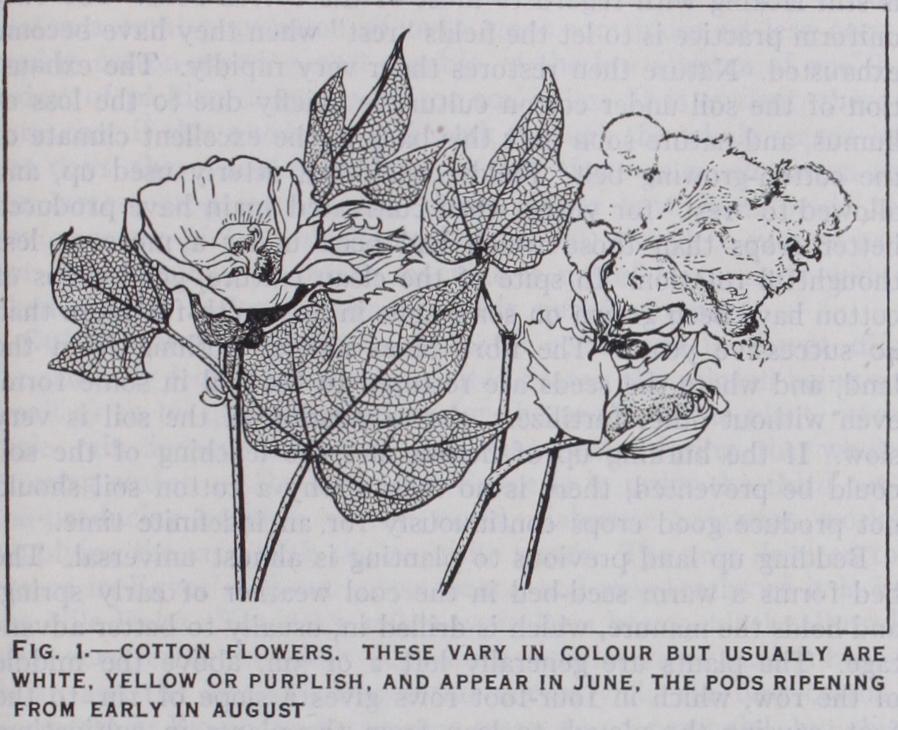

Microscopic examination of a specimen of mature cotton shows that the hairs are flattened and twisted, resembling somewhat in general appearance an empty and twisted fire hose. This charac teristic is of great economic importance, the natural twist facili tating the operation of spinning the fibres into thread or yarn. It also distinguishes the true cotton from the silk cottons or flosses, the fibres of which have no twist, and do not readily spin into thread, and for this reason, amongst others, are very considerably less important as textile fibres. The chief of these silk cottons is kapok, consisting of the hairs borne on the interior of the pods (but not attached to the seeds) of Eriodendron anfractuosum, the silk cotton tree, a member of the Bombacaceae, a family very closely allied to the Malvaceae.

Botanical Classification.—Considerable difficulty is encount ered in attempting to draw up a botanical classification of the species of Gossypium. Several are only known in cultivation, and we have little knowledge of the wild parent forms from which they have descended. During the periods the cottons have been cultivated, selection, conscious or unconscious, has been carried on, resulting in the raising, from the same stock probably, in dif ferent places, of well-marked forms, which, in the absence of the history of their origin, might be regarded as different species. Then again, during at least the last four centuries, cotton plants have been distributed from one country to another, only to render still more difficult any attempt to establish definitely the origin of the varieties now grown. Nevertheless it is possible for prac tical purposes to divide the commercially important plants into five species, placing these in two groups according to the char acter of the hairs borne on the seeds. Sir G. Watt's exhaustive work on ti'Vild and Cultivated Cotton Plants of the World is a recognized authority on the subject ; and his views on some de bated points have been incorporated in the following account.

A seed of "Sea Island cotton" is covered with long hairs only, which are readily pulled off, leaving the comparatively small black seed quite clean or with only a slight fuzz at the end, whereas a seed of "Upland" or ordinary American cotton bears both long and short hairs; the former are fairly easily detached (less easily, however, than in Sea Island cotton), whilst the latter adhere very firmly, so that when the long hairs are pulled off the seed remains completely covered with a short fuzz. This is also the case with the ordinary Indian and African cottons. There remains one other important group, the so-called "kidney" cottons in which there are only long hairs, and the seed easily comes away clean as with "Sea Island," but, instead of each seed being separate, the whole group in each of the three compartments of the capsule is firmly united together in a more or less kidney-shaped mass. Starting with this as the basis of classification, we can construct the fol lowing key, the remaining principal points of difference being indicated in their proper places : i. Seeds covered with long hairs only, flowers yellow, turning to red.

A. Seeds separate.

Country of origin, Tropical America—(I) G. barbadense, L.

B. Seeds of each loculus united.

Country of origin, S. America—(2) G. brasiliense, Macf.

ii. Seeds covered with long and short hairs.

A. Flowers yellow or white, turning to red.

a. 3 to 5 lobed, often large.

Flowers white.

Country of origin, Mexico—(3) G. hirsutum, L.

b. Leaves 3 to 5, seldom 7 lobed. Small.

I Flowers yellow.

I I Country of origin, India—(4) G. herbaceum, L.

I B. Flowers purple or red. Leaves 3 to 7 lobed.

l Place of origin, Old World—(5) G. arboreum, L.

I. G. barbadense, Linn. This plant, known only in cultivation, is usually regarded as native to the West Indies. Watt regards it as closely allied to G. viti f olium, and considers the modern stock a hybrid, and probably not indigenous to the West Indies. He classifies the modern high-class Sea Island cottons as G. bar badense, var. maritima. Whatever may be its true botanical name it is the plant known in commerce as "Sea Island" cotton, owing to its introduction and successful cultivation in the Sea Islands and the coastal districts of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida. Its cultivation in these regions has now been abandoned on account of the ravages of the boll weevil, and it is now confined to the dryer islands of the West Indies, having been reintroduced there from the United States. It yields the most valuable of all cottons, the hairs being long, fine and silky, and ranging in length from to 22in.

Egyptian cotton is usually regarded as being derived from the same species. Watt considers many of the Egyptian cottons to be races or hybrids of G. peruvianum, Cay. Egyptian cotton in length of staple is intermediate between average Sea Island and average Upland. Besides being cultivated in Egypt, this cotton is also grown under irrigation in the United States, in Arizona and California, where new strains have been produced, notably Pima and Yuma. Its cultivation has also been extended to the newly irrigated areas of the Sudan. It has, however, certain char acteristics which cause it to be in demand even in the United States, where during recent years Egyptian cotton has comprised about 6o% of all the "foreign" cottons imported. These special qualities are its fineness, strength, elasticity and great natural twist, which combined enable it to make very fine, strong yarns, suited to the manufacture of the better qualities of hosiery, for mixing with silk and wool, for making lace, etc. It also mercer izes very well. Commercial varieties of Egyptian cotton have only a limited life and the variety known as Sakellarides has, to a great extent, replaced Mita fi fi and Yannovitcli, which were formerly the best known and most exclusively grown varieties. Sakellarides is said to be deteriorating in the same way.

2. G. brasiliense, Macf. (G. peruvianum, Engler), or kidney cotton. Amongst the varieties of cotton which are derived from this species appear to be Pernambuco, Maranham, Ceara, Aracaty and Maceio cottons. The fibre is generally white, somewhat harsh and wiry, and especially adapted for mixing with wool. The staple varies in length from i to about i 2in.

3. G. hirsutum, Linn. Although G. barbadense yields the most valuable cotton, G. hirsutum is the most important cotton-yielding plant, being the source of American Upland cotton. It is the only cotton grown without irrigation in the American cotton belt. The staple varies usually in length between a and ilin. According to Watt there are many hybrids in American cottons between G. hirsutum and G. mexicanum.

4. G.

herbaceum, Linn. Levant cotton is derived from this species. The majority of the races of cotton cultivated in India are often referred to this species which, according to some bota nists, is considered to be closely allied to G. hirsutum and has been regarded as identical with it. The fact that American and Indian cottons have not been hybridized successfully indicates, however, that they are quite distinct species. The Indian cottons are usu ally of short staple varying from about to 'in. according to the race grown. Different grades of cotton in India have trade names according to the districts where recognized types are prin cipally cultivated. The most important of these are Tinnivelly, Broach, Hinganghat, Dharwar, Amraoti, Bengal, Sind and Kumpta.Much has been done within recent years by the several pro vincial departments of agriculture to improve the staple of Indian cottons by selection and breeding, and large sections of the country now produce a "staple" cotton which, in many respects, is not inferior and, in some respects, superior to middling American cotton.

5. G. arboreum, Linn. This species is often considered as in digenous to India, but Dr. Engler has pointed out that it is found wild in Upper Guinea, Abyssinia, Senegal, etc. It is the "tree cot ton" of India and Africa, being typically a large shrub or small tree. The fibre is fine and silky, of about an inch in length. In India it is known as Nurma or Deo cotton. Commercially it is of comparatively minor importance.