Commerce in Cotton Yarns

COMMERCE IN COTTON YARNS One of the strangest features of the buying and selling of cotton yarns in Great Britain is that there is no fixed form of contract, and this leads to many disputes. Notwithstanding however, the absence of a contract when the magnitude of the trade done is taken into consideration it is surprising that the occasions on which the aid of the law is invoked are so very few.

Manchester is the largest centre in the world for the yarn trade ; every mill is represented on the Manchester Royal Exchange and the whole of the yarn production of Lancashire and the adjacent counties is sold on the floor of the exchange.

The beginning of a transaction in yarn starts with the merchant who ships the woven cloth to customers overseas. He makes an enquiry for a quotation for a stated number of pieces of cotton cloth, at the same time setting out the particulars of width, length, number of threads in the warp, number of threads in the weft, counts of both warp and weft, and style of cloth to be woven. The manufacturer, before he can complete his calculation, approaches the yarn spinner to get an idea of the price at which he must base the yarns, and having got this he then proceeds to make up his calculation.

The commercial side of yarn selling has been very much criti cized since the World War; many mills have been accused of weak selling and by doing so to have kept the market price below the economic level. It is not possible to have a fixed price for a par ticular count of yarn as so many factors enter into the cost of spinning; what would be a profitable price to one mill would be a serious loss to another.

Few people outside those who are actively interested in the trade realize how very fine is the margin upon which spinners work as regard prices and it may be stated that if spinners had $ of a penny or even of a penny net profit after all expenses had been paid on every pound of yarn spun the spinning trade would be prosperous.

The two sections of the yarn spinning trade are the American section and the Egyptian section. The American section is the largest as regards number of spindles operated and the bulk of the yarn spun in this section is sold by the mills direct to the manu facturer, who converts the yarn into cloth.

Yarn, as is shown in detail elsewhere in these articles, is spun in many ways. Weft (that is the yarn used across the cloth) is only spun either with the turns put in the yarn from right to left, or reversed, but twist is often spun in a variety of ways, single, double, two, three, four and more folds and sometimes mixed with other fibres such as artificial silk, ramie, wool, worsted, etc. The American section of the spinning trade embraces mills which use cotton grown in America, India, British colonies and other countries outside Egypt and the Sudan. The yarn used for weft is made up into cops; these have either pasted bottoms, or they may be on short paper tubes or long paper tubes according to the requirements of the manufacturer.

The yarn is packed into cane skips by the spinner, each skip containing about 300 lb. weight. The twist yarn which is used for the threads in the lengthway of the cloth may be delivered to the manufacturer in different ways. As there are two kinds of twist, mule and ring, the particular kind required often determines the form in which it is to be delivered. If the manufacturer requires single cop twist it is packed into skips in a similar manner to the weft, but if ring twist is required, after spinning it is wound on to bobbins and from bobbins to beams, each beam containing about Soo ends; it is quite common for one of these beams to contain i,000,000yd. of yarn of medium counts.

If the yarn required is to be doubled yarn it is sent from the spinning mill to the doubling mill, where two or more threads are twisted together. This is often done when the yarn is to be pol ished or mercerized. The yarn may have to go through the further process of gassing; that is, the yarn is passed over specially made gas jets where the outstanding hairs on the yarn are singed off leaving a smooth and uniform thread. This is done when it is in tended to use the yarn for making special cloths such as voiles, poplins and similar high-class fabrics.

The Egyptian yarn is treated much in the same way as the American, but as Egyptian cotton is longer stapled than the American it is used for the finer counts of yarn.

American cotton is spun from is to 6os and 745 but rarely be yond 7os, and whilst Egyptian may sometimes start at los, the lowest counts are between 20s and 3os and go finer up to 25os and 3oos.

It will be seen that there is therefore a great difference between the two sections, but as the product of each section is so inter mingled by the manufacturer in the thousands of different kinds of cloth made in Lancashire the marketing of both classes of yarns must be on a somewhat similar basis.

The absence of a stated form of contract leaves the marketing of the yarn production in what seems more or less a state of chance. This is more apparent than real, because although the arrangement for the sale and purchase of yarn is by word of mouth, usually on the Manchester Royal Exchange, it is gener ally confirmed by a sale note later, which sets out the weight of the transaction, price per lb., counts of yarn, quality and what kind (twist, weft, beams, bundles, cheeses, ball warps, section warps, chains, etc.). The note may state the time and rate of delivery, but this is not always done. The manufacturer may want only a certain quantity each week or month, and the delivery may be "as required" or it may be a definite weight per week or month.

If the yarn bought is ring twist on beams the buyer has to stip ulate the number of ends on a beam or sett of beams and the length required. It is the usual practice for a spinning mill to spin a range of ten to 12 counts of yarn, but as the manufacturer may require as many as 5o different counts at one time he cannot keep large stocks of each different count, and he has to keep a vigilant eye on yarn deliveries so as to ensure that he is not overstocked in one particular count and at the same time have machinery waiting for another count.

The quality of yarns, even of the same counts, vary and one spinning of a particular count might be quite satisfactory for one cloth whilst it would be unsuitable for another kind of cloth. The prices for similar counts of yarn vary as between mill and mill, and it is the business of the manufacturer to find out the particular class of yarn suitable for putting into the cloth he has contracted to make.

Selling the Yarn.—The selling of the yarn production is mostly done in Manchester, sometimes by a salesman employed by the spinner and sometimes through an agent. When the trans action is between the actual spinner and the actual manufacturer the terms of payment are 21% discount for cash in 14 days, but if through an agent and the agent guarantees the account to the spin ner, the agent pays cash and deducts 4% from the invoice, allowing the buyer the usual 21% for payment in 14 days. The difference between the 21% and the 4% being the agent's remuneration. This method may be slightly varied at times and for big orders, but the general practice is as stated. Since the World War the number of agents has increased and there is a large number of those ac tively engaged in the cotton trade to-day who think that this is a charge on the cotton industry, intolerable in times of prolonged trade depression.

The export trade of yarns is done through established and repu table merchants, but the quantity of yarn exported, apart from the Egyptian qualities and American special yarn, is not great in pro portion to the quantity spun. Great Britain seems to have lost a great part of her export trade of cotton yarn. There are two rea sons for this, first the small quantity available during the years of the World War and secondly the high prices prevailing since the war. There is another factor which has an adverse effect on British export trade, and that is the increased number of spindles now installed in countries such as India and China who both pro duce much yarn for their own consumption. India formerly was a good market for Lancashire yarn, especially the higher medium and finer counts. It used to be said that the Lancashire climate being generally humid was the necessary atmosphere required to spin good yarn, but the great advances made by mill engineers in producing artificial atmospheric conditions in any type of shed and in any country has robbed Lancashire of what was hitherto her supremacy in this direction.

As the tendency is for all the cotton manufacturing countries to increase the number of their spindles, there does not appear to be too bright a prospect of Lancashire recapturing the trade, and the British home market will have to be cleared of a lot of un necessary charges if sufficient cloth is to be sold to absorb the whole of production the spindles of Lancashire are able to turn out.

One of the results of Great Britain's former customers making more and more of the coarser qualities of cloth for their home consumption has been that Lancashire turned to finer fabrics. Now finer fabrics require finer counts of yarn, and the finer the yarn the less it is in weight. It is not possible for every spinning mill to spin fine counts; neither is it possible for every weaving shed to weave fine or fancy fabrics, and in those weaving sheds where fancy goods are made it is necessary to mingle the fancy and plain woven goods, as too many looms tended by a single weaver weaving fancies would not make for efficient work. A further factor bearing on the manufacture of the plain, coarser class of cloth is that the automatic or mechanical feeder loom has not been adopted in Great Britain to any extent. Several at tempts have been made to install them, but with the exception of not more than half a dozen mills these mechanical looms have been discarded. On the other hand, competing countries have adopted them not because they can be made to weave cloths cheaper than the Lancashire type of loom, but because more looms can be tended by an individual worker.

The only hope for Great Britain to absorb the productive ca pacity of her spindles is for Lancashire to return to the system of more or less sectionalizing cloth production and producing on mass production lines which have been so successful elsewhere.

Prior to 1914, Lancashire may be said to have been on mass production lines, not because each mill was making the same kind of cloth for prolonged periods, but rather because each cotton town and its immediate neighbourhood were engaged on the same material. The beginning of the war saw a decline in British trade; mills in different towns began to compete with each other and the various styles, designs and fabrics began to be made all over Lan cashire. When the war was over and British competitors had cap tured their own home markets in the coarser cloths they then en tered some of the markets which up to 1914 had been exclusively British. A world impoverished by war could not afford to buy Lancashire products at their enhanced price and so were forced to purchase the cheaper if coarser products made elsewhere. Fashions too have a decided effect on the demand for cotton yarn and cloth. The prevailing effect of the post-war styles of dress has meant a very serious shrinkage in the quantity of cotton cloth required. Much cloth has been made containing threads or stripes of artificial silk; this has undoubtedly helped the British export of cotton yarn and cloth.

When it is remembered that over

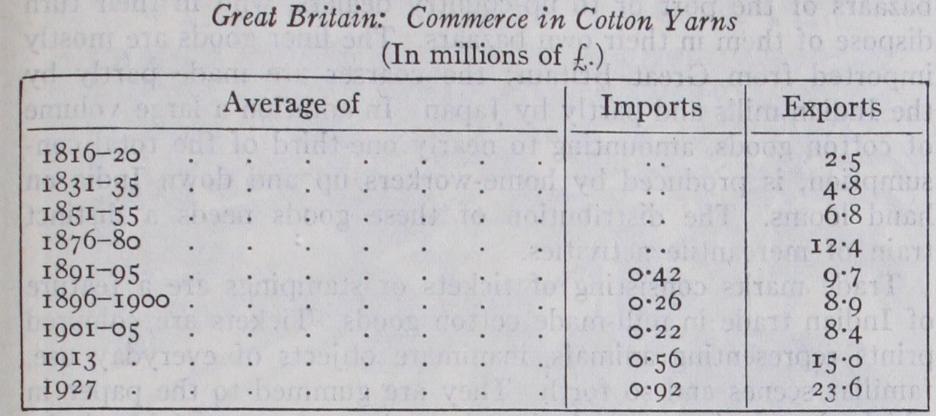

75% of the cotton cloth woven in Great Britain is for export, it will easily be seen that any falling off in these exports has a serious effect on the Lan cashire trade. The custom of foreign markets is vitally necessary to the British cotton industry; without it mills must run short time and costs of production are increased both for home and foreign trade.The accompanying table shows, in millions of £, the value of the British commerce in cotton yarns for the period 1816-1927: