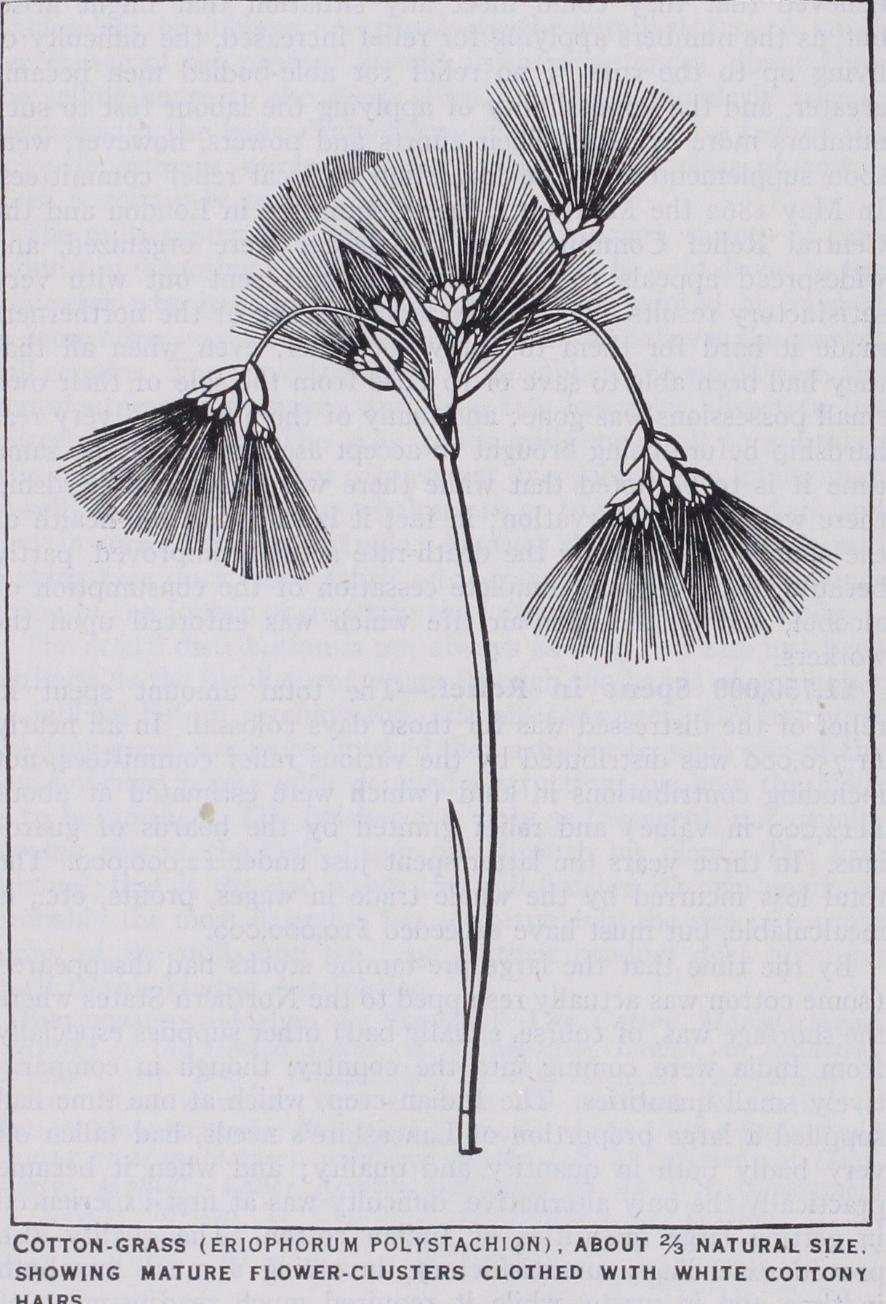

Cotton-Grass or Cotton-Sedge

COTTON-GRASS or COTTON-SEDGE is the name ap plied to species of Eriophorum, a genus of the sedge family (Cyperaceae). There are 15 species, four being British and ro North American. They are generally found on wet and boggy moors. The flowers are massed together into heads and each has four or more hair-like bristles at the base. After fertilization these grow out into long conspicuous cottony hairs which serve to distribute the seed which is contained in a small dry achene. The alpine cotton-grass (E. alpinum) and the slender cotton grass (E. gracile) occur both in Great Britain and in North America. The Virginia cotton-grass (E. virginicum), with dingy brown, rarely white, bristles, grows from Newfoundland to Mani toba and southward to Florida and Nebraska. The sheathed cot ton-erass (E. callithrix) . found from Newfoundland to Pennsyl vania and Wisconsin and northward to the Arctic, and also in Asia, forms in Alaska the summer food of reindeer.

Fifty years ago the cotton planters of the United States were greatly troubled by the enormous amount of seed that accumulated each year and were at a loss as to a means of disposing of this surplus, which, not being required for planting, was of no use to them. The introduction of the cotton "gin," a machine for separating the cotton from the hull containing the seed, increased the production of cotton, but, at the same time, aggravated the cotton-seed nuisance. The ginners, therefore, took the seed to a remote spot and left it to rot or dumped it into a convenient stream of running water. The situation eventually became serious, and in 1857 laws were introduced in various States of America making it a punishable offence to accumulate seed around a ginnery to the detriment of the health of the inhabitants of the city, town or village, or to throw cotton-seed into a "river, creek, or other stream of water which may be used by the inhabit ants for drinking o'r fishing therein." Some thrifty farmers utilized the seed as a fertilizer, a use it still has, but only after the valuable oil has been extracted.

Although large quantities of cotton-seed were being allowed to rot in the United States up to about 187o, in Great Britain, curiously enough, where no cotton could be grown, an attempt was being made to promote the extraction of the oil from the seed. It is on record that in 1783 the Royal Society of Arts offered a gold medal to "the planter, in any part of the British islands of the West Indies, who shall express oil from the seed of cotton and make from the remaining seed hard and dry cakes, as food for cattle." The medal, it is stated, was never applied for. In the United States the extraction of the oil appears to have been under taken in a few places only in the early part of the r 9th century. There is a record, for instance, of an oil mill in Columbia in 1826. Even earlier. in 1804, a chemist and druggist of Philadelphia carried out some experiments with cotton-seed oil, but did not fulfil his intention to erect a factory in New Orleans. In 1 818 a Col. Clark experimented with cotton-seed oil for burning in lamps, and the oil was quoted in a paper published in 1829 at $8o per gallon. In 1852 a New Orleans linseed oil manufacturer produced a small quantity of oil from the cotton-seed, and is said to have sold it for medicinal purposes at $1 per gallon. (A gallon in the United States is smaller than in Great Britain.) In France the utilization of the seed was progressing more rapidly and there, using the cotton-seed from Egypt, the oil was refined and used for edible purposes before the middle of the 19th century. The quan tity of seed used for oil extraction in the United States in 188o was 182 tons; in 1926 5,558,00o tons were crushed. These figures show the rapidity with which the industry expanded from 188o onwards—even in ten years (188o-9o) it had increased nearly tenfold.

The cotton-seed of the United States is consumed in that country and only a small percentage of the total oil production is exported (over 20,000 tons in 1926). The seed is also produced in other countries, the three most notable being Egypt, India and Russia. In Great Britain Egyptian seed is mainly used, although Indian seed comes on to the market, the supply in this case being governed by the price reigning in Europe. When the price is attractive Indian seed will be obtainable, but, as India can con sume the seed it produces, exports are not the rule when European markets are unattractive. In 1926 the United States was by far the greatest producer of cotton-seed, the crop being given as 6,200,00o tons. India came next with 2,200,000 tons, and Egypt third with 672,00o tons.

As already stated, Great Britain imports the seed mainly from Egypt, and from this source 264,70o tons were received in 1926. Egypt also supplies the Continent of Europe, but not to such a large extent, the exports in 1926 being 35,80o tons. From India Great Britain received 70,70o tons of cotton-seed, more going to the Continent. This quantity was the lowest since 1921 and was considerably below the previous year (1925), when 299,70o tons were exported from India to Great Britain.

Cotton-seed Oil.

By far the most valuable product of cotton seed is the oil, which is largely employed for edible purposes (as a table oil) and in the manufacture of margarine. Besides these legitimate uses it is sometimes employed to adulterate olive oil and other edible oils, fats and lard compounds. Crude qualities find an extensive use in the manufacture of soap. It is not con sidered a suitable oil for lubricating purposes, although "blown" cotton-seed oil (oil that has been thickened by passing air through it) has been recommended for that purpose. Vegetable oils are usually divided into three classes : drying, semi-drying, and non drying. It is to the second class that cotton-seed oil belongs. By "drying" is meant that the oil on exposure to air will absorb oxygen and form a thick film. The semi-drying oils will do this only to a certain extent and do not harden completely.The seeds from various sources vary in character ; the Egyptian seed, for instance, has short fibres attached to it which can be removed by a process known as "delinting" ; the seed of the United States is not, however, easily "delinted" and therefore, while in Great Britain the seed is crushed in its hull, in America the hull is removed before the oil is extracted. To do this the seed is cut up by revolving knives in a machine known as a "huller." The small pieces of seed are then separated from the hulls, to which the short fibres still adhere, by sieving, the kernels (meat) passing through and the hulls being left behind. In Great Britain this process of "decorticating" is not employed for Egyp tian seed, but the resulting oil is darker in colour than the American. The oil of the latter country, however, owes its lighter colour also to the short time that elapses before the seed reaches the oil mill. Obviously the seed can be quickly passed to the crusher, but in Great Britain and on the continent of Europe con siderable time is taken up by the passage of the seed from one country to another. To this lengthened period is attributed the darker colour of the oil.

There are three main methods for extracting the oil : (I) by hydraulic pressure, (2) by compression caused by a worm con veyor and (3) by solvent extraction. The first is the most com monly used. In this process the seed, which has been cleaned and treated to enable the oil to be freed easily, is placed in containers, consisting in many cases of large perforated boxes or cages in which the seed is divided into sections by metal plates. When pressure is applied the oil is squeezed out through the perforations and collected. The meats or kernels are now compressed into slabs or "cakes," which may contain about 5% of oil. The second method is of more recent introduction. In a machine known as the "expeller," the seed is conveyed in a perforated cage by a worm conveyor (such as may be seen inside a domestic mincer), but it cannot readily escape and theref ore a pressure is created and the oil extracted, being forced from the seed through the perforations in the cage. This method, it is claimed, is continuous.

The solvent extraction process is the most efficient ; in fact, it is so efficient in its extraction of the oil that it is not favoured where the resulting cake is required for cattle feeding, for such cake must contain a percentage of oil. Also, when edible oils are required solvent extraction is not ideal as the flavour of the oil may be affected. There are many processes for solvent extraction, but the common principle is that the oil in the seed is dissolved and carried away by the solvent, which, at a later stage, is removed and reclaimed for further use. The crude oil obtained from the presses is dark in colour and has to be refined before it can be employed for edible purposes. A preliminary treatment may con sist of adding a dilute solution of caustic soda, which combines with what are known as "free fatty acids" (objectionable sub stances in edible oils, but useful to soap manufacturers), and removes colouring matters. Fuller's earth may also be used for bleaching and deodorization.

The amount of oil contained in the seed may vary according to the country of origin. The following table shows the results obtained by Lewkowitsch from several varieties of seed :— Lewkowitsch points out that the figures given for the oil con tent of Bombay seed are somewhat high; the average percentage of oil in Bombay seed, he says, is about 18.

The United States has by far the greatest output of cotton-seed oil, the production in 1926 amounting to 780,337 tons, while the average for the five years to 1924 is given in Frank Fehr and Company's Review of the Oilseed and Oil Markets as 520,000 tons. In Egypt the estimate for the 1926-27 production was 35,00o tons; in Great Britain 96,630 tons were produced in 1926 and in Germany 5,375 tons. Exports of cotton-seed oil from the United States have fallen, and a considerable decline was shown during the years 1916-26. In 1916 the United States sent out 188,214, 000lb.; in 1926 the total was down to 40,900,000lb. Imports of cotton-seed oil during these ten years were highest in 1919, when the total reached 27,806,000lb. The quantity then fell rapidly until in 1923 it was as low as 2 5,0441b. ; from 1924 to 1926 it has not been shown separately in the returns. It should be pointed out that although the exports of oil were low in 1926 the produc tion was high, showing that consumption in that country had increased.

The exports of refined cotton-seed oil from Great Britain during 1926 amounted to 19,906 tons, the principal importing countries being the Netherlands (6,638 tons), France (2,531 tons), and the United States (2,462 tons). According to experiments by Daniels and Louglin,' published in Journ. Biol. Chem., 1920, xlii., 359, and quoted by Wright and Mitchell, cotton-seed oil contains appreciable quantities of fat-soluble vitamines, a growth-promot ing constituent.

Cotton-seed Cake.

When the oil is expressed from the seed by pressure, slabs or cakes remain in the press, and these form a foodstuff for cattle. In some presses the edges of the cake will contain an excess of oil, and these are pared off and pressed again to extract the surplus oil. In the press mentioned in this article the edges are not usually saturated, and the cake is ready for con sumption. In some cases the cake is ground up and sold as meal. The cotton-seed cake is one of the most valuable for feeding cattle.The following are the results of analyses of a cotton-seed cake and cotton-seed meal by A. Smetham, published in the Journal of the Royal Lancashire Agricultural Society in 1909. Andes in his Vegetable Fats and Oils gives these figures and adds another, the first.

The value of cotton-seed meal as a cattle food has been corn pared with that of corn and oats and the respective values are set out below :— Andes states that in calculating the value of a food it is usually assumed that the albuminoids and oil are equal in value and that they possess two and a half times the feeding properties of the carbohydrates; therefore the "food units" are calculated by adding together the percentages of albuminoids and oil, multiplying by 21, and adding to these the percentage of carbohydrates. In this way a number is obtained which is supposed to represent the feeding value of the particular food. Andes gives the following examples:— Food Units Cotton-seed Cake . 44•09+14.23 X 21+20.85 166 Linseed Cake . . . . 28.56-f-IO.6OX 21+32•09 13o Coconut Cake . 19.51+I0.90X21+40.26 116 Palm Kernel Cake . 16.2o-1-I0.98X21+37.38 105 The greater part of the cotton-seed cake and meal exported from Great Britain goes to the Irish Free State. In 1926 exports to all countries amounted to 4,444 tons, 3,361 tons of which were sent to the Irish Free State. A considerable quantity of cotton-seed cake is imported into Great Britain. In 1926, 265,213 tons were received, in 1925, 220,982 tons, and in 1924, 167,775 tons. From India and Burma, 5,773 tons of cotton-seed cake were exported, 2,746 tons going to Great Britain, 2,7 20 tons to Germany, and 307 tons to other countries.

Cotton-seed Stearin.

This is made by cooling the cotton seed oil, which causes a light-yellow fat to separate out. This fat, known as cotton-seed or vegetable stearin, is used in the manu facture of lard and butter substitutes.

Products from Cotton-seed.

It has been pointed out already that cotton-seed is used for edible purposes and for soap making. It can also produce a stearin pitch, which finds a use in insulating materials, artificial leather, etc. It provides an oil for miners' lamps and, in certain cases, is made use of in grinding pigments for paints. By hydrogenation the oil can be converted into a cooking fat, which is used in the bakery trade. The oilcake or meal may be used for fertilizing as well as for feeding cattle. The hulls, too, prove valuable for fertilizing. Cotton linters provide cellulose, which can be nitrated to form nitrocellulose, which, besides "gun cotton," is a raw material for the rapidly expanding cellulose lacquer industry.The various products from cotton-seed and the uses to which they can be put have been arranged by Grimshaw as follows (the products from linters have been added by the writer, but it must be remembered that there are many other sources of cellulose, and cotton linters may not be used by some manufacturers) :— As indicated previously, the amount of oil contained in seeds from different countries varies, and the quantity of oil obtained depends upon the method of extraction ; but the figures given by Grimshaw serve as an approximate picture.