Cotton Industry in the United States

COTTON INDUSTRY IN THE UNITED STATES The early history of cotton in America is obscure, its use pre dating all authentic records. Columbus, on his voyage of discov ery in 1492, noted in his diary that "they [the natives] came swimming towards us and brought us parrots, balls of cotton thread, etc." He and other explorers found cotton growing abun dantly in the West Indies and continental America, and the natives skilled in spinning and weaving. The art of spinning and weaving cotton seems to have originated in Peru and spread northward. Samples of fabric have been found that are believed to antedate the Christian era.

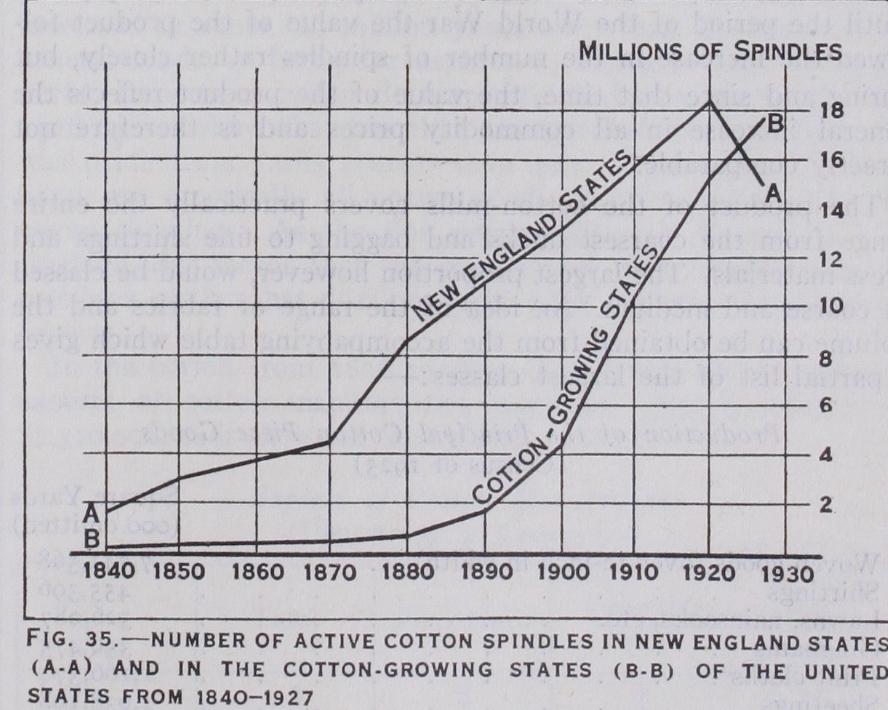

The cotton-mill era is usually considered to have started in the United States in 1790 with the erection and equipping of a mill in Rhode Island under the direction of Samuel Slater. Several other mills were erected prior to this date, but did not continue in oper ation. Expansion was slow for the next 15 years, or until the Em bargo of 1807, the Non-Intercourse Act and the War of 1812 interfered with the importation of cotton cloth from England. The consequent high price of cotton cloth attracted investors to this form of industry and the expansion from then on was fairly rapid. The invention of the power loom by Lowell in 1814, and the invention of the ring frame by Thorp in 1828, aided materially in this expansion. Abundant water-power, available capital and adequate labour tended to centralize the industry in New England for many years, although a few mills were established in the Mid dle Atlantic and Southern States. The Civil War, 1861--65, cut off practically the entire supply of cotton from New England and the industry suffered severely. By 1870 cotton was again avail able and the expansion, temporarily stopped by the war, was con tinned. Most of the early growth was in New England, and it was not until 188o that any expansion took place in the cotton-growing States. Since that time progress has been rapid and the cotton growing States now have more spindles in place than New Eng land. While the South has been expanding rapidly, New England had a more gradual expansion up to 1923. Since then the number of spindles in New England has decreased slightly.

Statistical data for the early years are meagre and at times lacking. Comparisons of existing statistics are not always en tirely accurate, as the methods of collecting and compiling have changed from time to time.

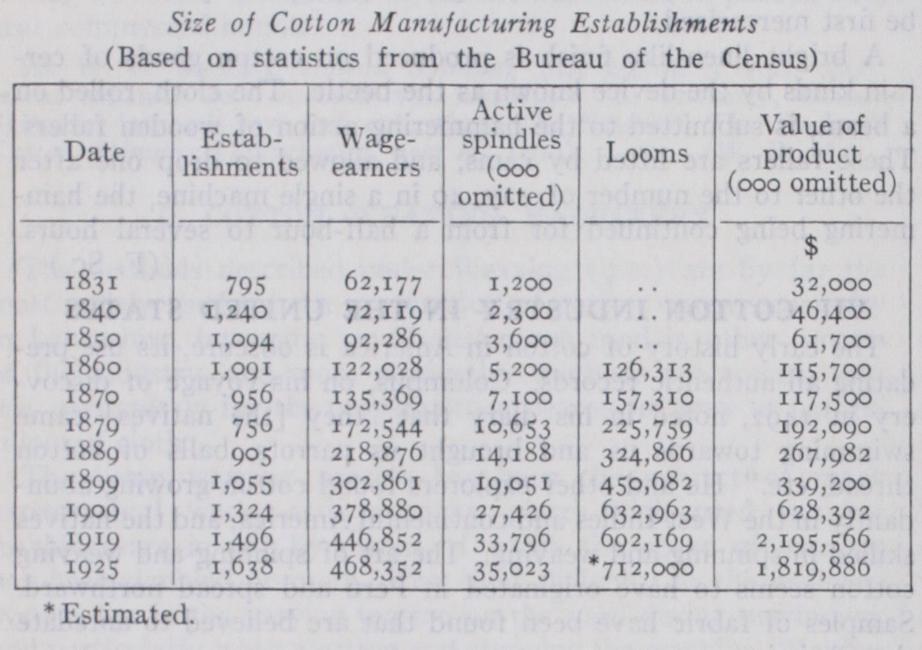

The following table shows the growth of the industry:— Prior to 'goo what are now classed as "cotton smallwares" were included with cotton goods. The tendency for the smaller plants to combine or go out of business was apparent after 1840 and continued until after 188o in New England, but the building of many small plants in the South increased the total number of establishments for the country. The number of spindles serves as the best unit for measuring the growth of the industry. In 1850, there were three times as many spindles as in 1831. Since the number of spindles has approximately doubled every 25 years. Until the period of the World War the value of the product fol lowed the increase in the number of spindles rather closely, but during and since that time, the value of the product reflects the general increase in all commodity prices and is therefore not directly comparable.

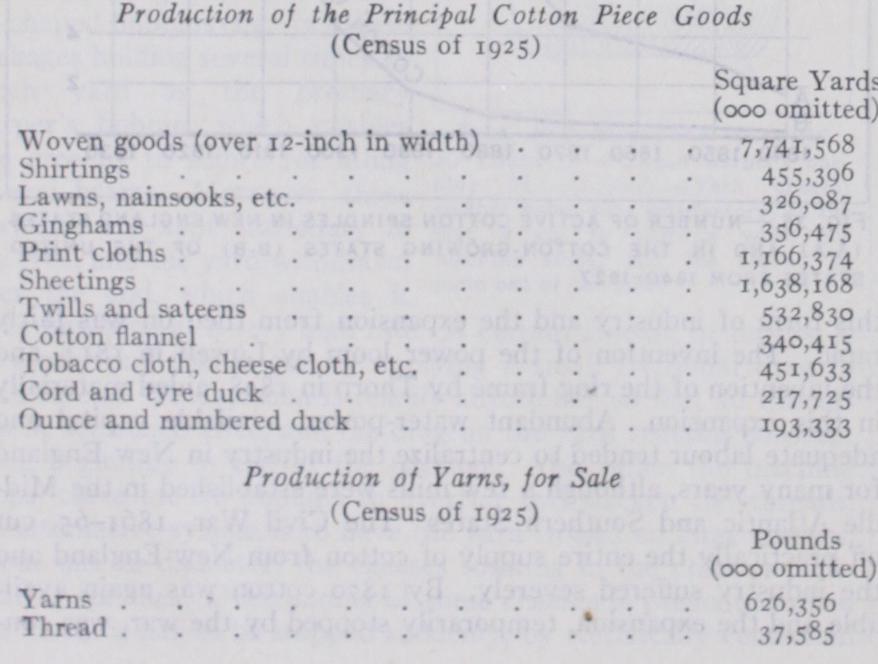

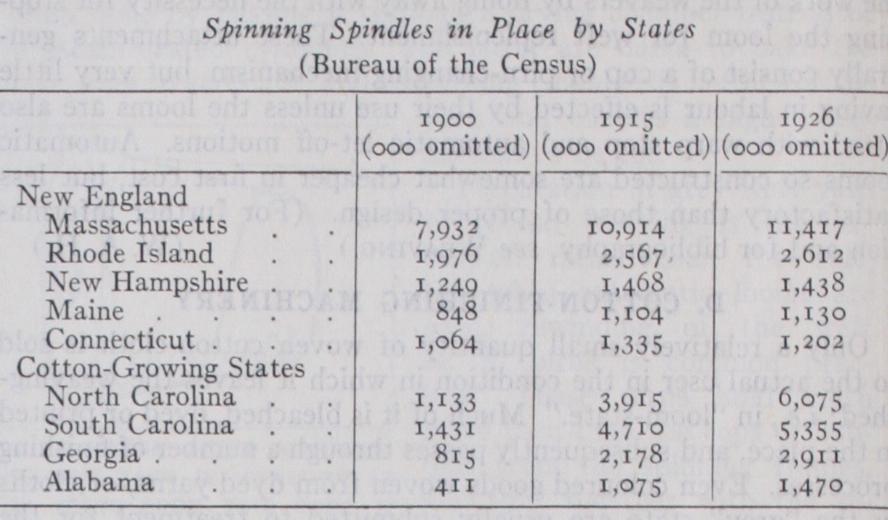

The product of the cotton-mills covers practically the entire range from the coarsest ducks and bagging to fine shirtings and dress materials. The largest proportion however, would be classed as coarse and medium. An idea of the range of fabrics and the volume can be obtained from the accompanying table which gives a partial list of the largest classes :— Distribution of Spindles.—The distribution of spindles in place in the principal cotton manufacturing States and the growth for the last 26 years are shown in the following table:— Expansion.—The causes of expansion in the South and the decline in the North are many and only the outstanding ones will be considered.

New England, because of its climate and soil, turned to indus try as soon as other sections of the country, more suited to agri culture, were able to supply its food requirements. The World War, by stopping unlimited immigration, created a shortage of labour which has since continued due to restricted immigration. The cotton industry, requiring as it does comparatively unskilled employees, suffered from competition with industries paying higher wages, and wages in the cotton industry were accordingly increased. Labour being put in a relatively strong position had many laws passed such as the 48-hour law and the law prohibiting employment of women or minors after 6 P.M. in the textile indus try in Massachusetts. At the same time the cotton industry, de pending primarily on domestic consumption, had to ship its prod ucts farther and farther as the centre of population moved west. This resulted in a higher transportation cost from New England than from some of the Southern States.

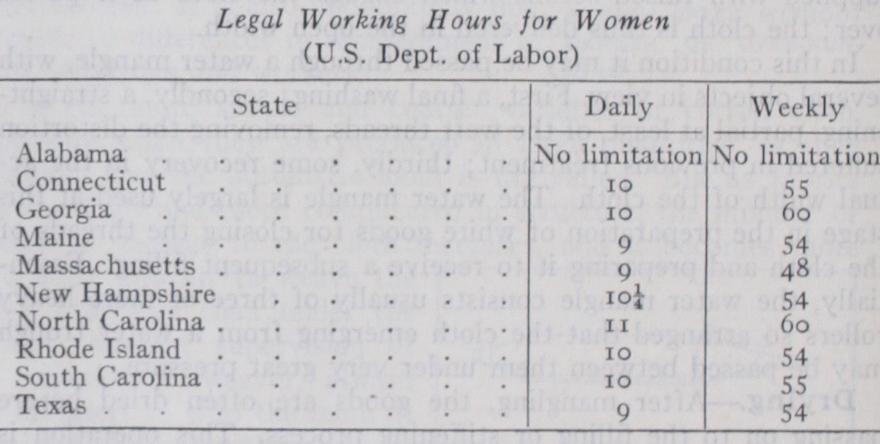

In the cotton-growing States industrial growth has been con fined almost wholly to cotton manufacturing, so that with the lack of competition between industries, wages have remained low. Be ing unorganized, labour has been unable to affect legislation, and as a result mills can operate 24 hours a day. Employees can work from S4 hours a week and up, some southern States having no limitations.

Nearness to the cotton field has not proved to be the advantage it was first thought as the cotton belt has rapidly moved westward, until now the freight rate from Texas, where the bulk of the cot ton is grown, to the cotton manufacturing States in the South is nearly as high as the freight rate into New England. The allow able hours of operation and the lower wage scale in the South have been the principle factors favouring the South over New England. Other causes, such as much higher taxes in New Eng land have also contributed to the rapid expansion of cotton manu facturing in the South. So far, the South has been able to oper ate with native white employees drawn from agriculture, but as the supply is not inexhaustible, competition for labour will be come increasingly important. Ultimately the South will have to face the problems now confronting New England, and higher wages with shorter hours will probably result. For many years cotton manufacturing centred in North and South Carolina but in recent years Georgia, Alabama and Texas have entered the manu facturing field.

The table herewith shows the growth of the two sections :— In the North the number of spindles increased steadily until 1923. Practically all of the decrease in spindles since that time has been in Massachusetts, where the effect of the 48-hour law for the employment of women and minors, began to show itself by driving some of the spindles from Massachusetts to the South. The substitution of rayon for cotton yarn has been more extensive in New England and has also contributed to the decrease in the number of active spindles. While the South did not pass New England in the number of active spindles until 1925, it passed New England in the consumption of cotton in 1910. This in creased use of cotton in the South reflects the tendency of the New England mills to concentrate on fine goods, while the South produces the heavy goods. The longer hours of operation which obtain in the mills of the South also tend to increase the productivity per spindle.

Power.

The tremendous growth of the industry is well illus trated in the accompanying table giving statistics on prime mov ers, generators and motors for the years 1899 and 1925. The num ber of prime movers, engines, turbines, etc., increased from 3,152 to 125,799 and the horse-power increased from 795,834 to 630. The development of the electric motor and its rapid adoption by the cotton industry is shown by the increase from 28o motors with a horse-power of 17,S94 in 1899 to 189,439 motors with a horse-power of 1,463,454 in 1925. These figures also bring out the increased use of the individual drive, the horse-power per motor decreasing from the figure of 62.o to that of 7.7 in the 26 year period.country depended on imports for its finer fabrics of highest quality. Gradually, as the operators became more skilled, the in dustry manufactured finer goods in addition to the coarser goods. The passing of the whaling industry about 1886 left a large amount of capital available in and around New Bedford. This capital was utilized in building mills designed and equipped to make finer cottons. The fine goods industry has centred around New Bedford since that time. The impression that it is necessary to go abroad for finer fabrics still remains and has been fostered by retail stores. As a matter of fact, the cotton-mills in the United States can manufacture cotton cloths that would compare favourably with any that can be imported. There are certain types of fabric made on hand looms, of which only a limited yardage is used, that the industry does not attempt to make.

The cotton industry has always been dependent, to a large ex tent, upon the domestic market for the consumption of its pro duction. The relative scarcity of labour compared to the other cotton manufacturing countries has kept the labour costs at such a level that competition with other countries in foreign trade could only be met on a comparatively few fabrics where volume production on automatic machinery has kept the labour cost at a minimum. Labour costs in the United States have been consist ently above the labour costs in foreign countries, but the indus try has had more or less protection by means of an import duty. This import duty has for the most part been fairly adequate, al though at times the tariff was not sufficient to enable domestic mills to compete with foreign mills on certain classes of fabric and ioo's yarn is about the finest that can be spun in competition with England, even with the tariff protection. The constant threat of competition from abroad has brought about a tendency towards mass production. The economies of automatic machinery and large scale production have enabled the mills to produce the coarser and heavier fabrics at a cost that allows the mills to com pete to a limited extent in foreign markets.

Until recent years no consistent attempt was made to export cotton fabrics in quantity. For a period prior to the Civil War, when American vessels were available, a fairly extensive trade was carried on with Japan, China and other countries in the Far East. Some of the trade-marks established at that time are still in active demand in the Orient. The yardage of cotton cloth im ported exceeded the yardage exported until 1876 when exports increased to about ten million yards more than the imports, the general tendency being for exports to increase faster than im ports. Imports of cotton cloth are principally on fine goods. The 1926 figures show that less than one-third of the total imported was made from yarns coarser than 4o's. Exports, on the other hand, are practically all coarse goods such as ducks, drills and heavy sheetings. As the fine goods mills are centred in New England, this means that the competition from imports must be met by a section that does not receive the compensation from the exports.

In the period from 1826 to 186o the average annual value of exports of cotton manufactures increased from $1,200,00o to $7,310,000, as is shown in the following table:— Exports and Imports.—In the early days the cotton-mills manufactured only the heavier, coarser types of fabric and the From 186o to 1865 the Civil War practically stopped cotton manufacturing. It was not until about 187o that cloth was again exported in volume and not until 1877 that exports regained the 186o level. Exports in the years from 1877 to 1896 showed a gradual tendency to increase. Exports in these years were as follows :— From 1914 to date Canada has taken the largest volume of exports of any one country. South America, the West Indies and the Philippines have all increased their takings of cloth from the United States.

The geographical division of exports from 1916 to 1925 was as follows :— Since 1914 the World War has influenced the export market and the period from 1914 to 192o reflects the partial stoppage of exports from competing countries. During these years the supply of cotton cloth from England and Europe for export was limited and cloth from the United States supplied much of the demand. By 1921 these countries were again in a position to export, and exports from the United States dropped to about one-third the value of the previous year.

In 182o the annual value of

imports was about $9,000,000. This figure increased slowly to about $14,000,00o in 185o, then increased rapidly to about $38,000,00o in 186o. For the years 187o to 1890 the imports were less, varying from $23,000,000 to nearly $30,000,000. By 190o the value of the imports had increased to about $41,000,000, in 1910 $66,500,00o and in 192o over $13 7,000,000. Since 192o imports have decreased. In 1925 the value of imports dropped to slightly over $79,000,000.Figures showing the imports of countable cotton cloths are available from 1890 on and are given in the following table:— Exports until about 1906 were mainly to Asia, although Canada, Central and South America were constantly taking increasing quantities. The geographical division of exports from 1891 to 3.910 was as follows:— Textile Schools.—The need for special educational facilities to train men for the cotton industry was not appreciated in the United States as soon as it was in Europe. The first schools estab lished, the Lowell School for Practical Design in 1872 and the Rhode Island School of Design in 1878, taught only designing. The Philadelphia Textile school, established in 1884, was the first school to give instruction in all the various processes connected with cotton manufacturing. In New England the Lowell Textile school was opened in 1896, the New Bedford Textile school in 1899 and the Bradford Durfee Textile school in Fall River in 1900. The Lowell school has gradually increased its requirements in scholarship and has been authorized since 1914 to grant degrees of bachelor of textile engineering and bachelor of textile chem istry. The New Bedford and Fall River schools are devoted prin cipally to instruction in the manufacture of cotton. With the development of cotton manufacturing in the South, textile courses have been added at Clemson Agricultural college, Georgia School of Technology and North Carolina State College of Agriculture and Engineering. These schools, both North and South, offer an excellent opportunity to the student for study of both the theory and practice of cotton manufacturing under competent instructors.

Labour.

The first cotton-mills were operated by native em ployees. It was not until about 183o that these began to be replaced by English, Irish and other western European emigrants.As these displaced the native Americans, they in turn were dis placed by another group, the French-Canadians beginning about 1865. At about the same time emigration from southern and eastern Europe increased, and many Italians, Greeks, Lithuanians and Polish were employed in the mills. Later probably less than 40% of the New England cotton-mill employees were native Americans. In the South the operators are all native born of Anglo-Saxon crescent. These people are, for the most part, drawn from the southern hill counties. Children were employed in the early days but child labour has never been popular and has prac tically ceased. Mill-owners have found that children are ineffi cient, so that even where the laws still permit, children are seldom seen in a cotton-mill.

In the Northern States, labour is unionized to some extent but in the South unions are not tolerated. At times in the past, some of the unions have acquired some strength and importance, but due to a combination of circumstances, unions have not flour ished. The Mule Spinners Union had at one time the reputation of being the strongest textile union but their demands became so exorbitant that ring-spun yarn was substituted for mule-spun yarn, and the use of the mule has decreased. For the most part, the attitude of the labour leaders has not been one of co-operation.

Wages compared to many other industries in the United States have remained low, but compared with wages in foreign countries they have always been high.

These figures compare with an average in England for male workers of $11.5o per week and female of $7.00 per week, accord ing to a published statement by the Ministry of Labour of the British Government.

The custom of furnishing employees with homes at reduced rents has been largely discontinued in the North, due to the desire of the employees to receive all of their wages in the pay envelope. In the South many of the mills are situated away from cities or towns and the only homes available are those furnished by the mill. The mills in the South situated in such villages usually contribute to the comfort and education of the employees and their families by furnishing recreational centres, churches and schools. These schools have done much to reduce illiteracy in the South.

Inventors and Machinery.

The scarcity of labour and the resultant high wages in the United States as compared to England resulted in more attention being paid to inventions that would reduce the labour costs (see AUTOMATIC MACHINES ). One of the earlier inventions of importance was the ring spinning frame patented by John Thorp on Nov. 20, 1828. This invention reduced the cost of spinning appreciably, and ring spinning replaced mule spinning except on the finer numbers. The ring frames have been gradually improved until now only the finest yarns are spun on the mules. Machines have been made more nearly automatic, devices to eliminate handwork perfected, machines re-designed to handle larger units and machine parts so standardized as to be interchangeable.As mills increased in size the handling of cotton became a seri ous problem and mechanical distributors were successfully intro duced. The usual plan in 1928 was to open the bales in a room where the openers are. The cotton from the openers is blown or drawn through large pipes to the picker room, where it is discharged on to a conveyer belt. This belt carries the cotton along over the feed hoppers of the pickers and, by means of auto matically controlled gates, drops the cotton from the belt into the hoppers and maintains the cotton in the hoppers at a constant level. (See Pl. IV., fig. 3.) In a few of the latest mills conveyers have been utilized throughout for handling the stock. Where this is done the cotton from the openers is blown to the top floor of the mill where the pickers are situated and the stock in process passes down from floor to floor arriving on the ground floor at the shipping room as finished cloth. P1. V., fig. r shows a lap that has just come down from the picker room by a gravity chute and is starting across the card room on a conveyer belt. The laps are side-tracked at convenient points throughout the room. In some of the more modern spinning-rooms there are two levels of con veyor belts. The full boxes of "roving" travel on a lower belt and are side-tracked at convenient intervals. The empty boxes are returned on an upper conveyer belt. A dead end of a side track terminating in a weave-room carries full boxes of filling yarn ready for use in the magazine of the automatic looms. The main supply belt traverses the room near the windows. Warp beams are frequently moved from the "slasher" room to the back of the loom in cradles suspended from an overhead track, doing away with the lifting of beams.

The automatic loom is used extensively on plain cloths, to an increasing extent on fancy cloths, and has done much to reduce the cost of weaving. In weaving print cloths and narrow sheetings one weaver formerly ran six to eight plain looms. With the full automatic loom it is not uncommon to find as high as 72 looms to the weaver and occasionally as many as ioo. Assistants to weavers keep the supply magazines on the looms full of bobbins or shuttles, and the new warp beams are put in by operators who do nothing else. The weaver pieces up all broken ends and is responsible for the quality of the cloth. Pl. VII., fig. i shows the bobbin type of magazine and Pl. VII., fig. 2 shows the shuttle type of magazine. These pictures also bring another development, the use of individual drive for looms. In the automatic loom each warp thread supports a small thin piece of steel. When a warp thread breaks the piece of steel drops and engages with a device that automatically stops the loom. A feeler motion is attached to the "lay" and as long as the filling-yarn is in place the loom con tinues to operate. Should the filling-yarn break the feeler motion will automatically stop the loom. These two devices work so accurately that the moment either the warp or the filling-yarn breaks the loom is stopped and cannot be started again until the broken thread is pieced up. At one end of the loom there is a magazine where a supply of full bobbins is kept. As soon as a bobbin in the shuttle runs out the empty bobbin is ejected and the full bobbin inserted automatically with such speed that the loom does not pause. Another type of loom changes the entire shuttle instead of the bobbin. For a number of years the automatic bobbin feature was used almost entirely on looms weaving plain cloth, but with the perfection of the details of the magazine it is now being extensively used on "lobby" looms.

Spooling and "beaming" formerly took considerable time, but developments in recent years have accelerated these operations until it is now possible to "beam" at speeds up to Soo or 600yd. per minute. Some mills are now using a type of high speed spooler where the spinning-frame bobbins are fed in at one end and the full spools taken off at the other without any piecing up by hand. The machine consists essentially of a feeding device which puts the bobbins into place ready to be unwound by the winding attachment which winds the yarn from the bobbins on to the spool. The upper part of the machine travels over the spools on an endless track, and whenever it comes to a spool that is not winding it picks up the broken end and ties it to the loose end on the spool. As soon as the spools have the proper amount of yarn wound on them they are automatically thrown forward ready to be "doffed." After doffing the full spools are dropped on to a conveyer belt that passes down through the centre of the machine and carries the spools to one end where they are transferred to the beamer, Plate VII., fig. 4.

Two types of high-speed warpers are shown, one for warping the yarn from the spools made on the device just described, the other, Pl. VII., fig. 3, for warping from cones. The cone type of warper has distinct advantages over the old type of spool warper. It is possible to put more yardage on the cones than on the spools. When an end breaks there is no over-running due to the momen tum of the spools. In addition, it is possible to put each end under uniform tension, giving a more uniform and better weaving beam. Machines have also been developed for tying in new warps on the looms. The warp-tying machine, illustrated in P1. VII., fig. 5, picks up in turn each warp thread on the old warp and auto matically ties it to the corresponding thread on the new warp with a weaver's knot. There have been many other improvements, such as vacuum stripping of cards, that have not only accelerated pro duction but also make the mills desirable places in which to work.

Distribution.

The cotton-mills can be roughly divided into two classes, those making and finishing their product and those selling their product in the grey or unfinished state. The merchan dising and distribution methods of the two types of mill are, for the most part, rather different. A mill making and finishing its own product usually sells through a selling-house that may or may not be financially interested in the mill. The selling-house in turn sells the product to the manufacturer of dresses and other apparel, wholesalers or jobbers for re-sale to the retail stores. A small percentage of the product is sold, in some instances, direct from the selling-house to the retail store. This is particularly true in dealing with the large chain-store organizations and a few of the large department stores. The production of this class of cotton cloth is relatively small.The mills selling the cloth in the grey follow a variety of pro cedures in disposing of their product. It may be sold direct to the converter who has the cloth bleached, dyed, printed or finished in some other way, in accordance with what he believes the market will require. The converter sells to the jobber, the wholesaler, the manufacturer of garments and, in a few instances, direct to the larger retail stores. The grey goods mills may sell to a broker who in turn sells to either a converter or a jobber, the jobber may re-sell to smaller jobbers, wholesalers or to small converters and they in turn to the retail trade. Another class of grey goods mill making tyre duck, cord fabric, etc., may sell through the selling house to the jobber or direct to the larger manufacturing units.

The actual distribution is not always as simple as has just been outlined as the product may pass through the hands of a number of jobbers before reaching the ultimate consumer. Ordinarily, if the grey goods are to be finished they are sent to some one of the few finishing plants with detailed instructions on how the cloth is to be finished. The finisher acts only as the agent, not usually owning any of the cloth being put through his plant. The first method, that is the one where the mill finishes its own goods, is probably the most desirable but unfortunately the size of a great many of the mills and the type of their product does not lend itself to this kind of distribution.