Cotton-Spinning Machinery

COTTON-SPINNING MACHINERY The functions of the processes in the mill are as follows : (I) to reduce the highly compressed cotton from the bales into the greatest possible state of division, i.e., to the ultimate fibre, and at the same time to remove sand, leaf, broken seed and short fibres; (2) to form the fibres into a rope, or sliver, which can be atten uated by stages until it is thin enough to form the required thread; (3) to parallelize the fibres by drawing between rollers or by combing, and, at the same time, by combining and attenuating sev eral slivers, to increase the regularity of the material; (4) to in sert sufficient twist into the product of the final attenuation in order to make a firm thread; (5) where required, to combine one or more single threads into a folded yarn; and (6) to finish and prepare the yarn for transport. The fineness of a yarn is expressed by its count, which is the number of hanks (84oyd.) of that yarn which weigh i lb. The principal machines employed are : bale breakers, openers and scutchers ; carding engines or cards ; drawframes, and, for fine or high quality yarns, combers; speed or flyer frames; ring frames or alternatively mules, and where folded yarns are produced, winding and doubling frames; cleaning and gassing frames ; reels and bundling presses.

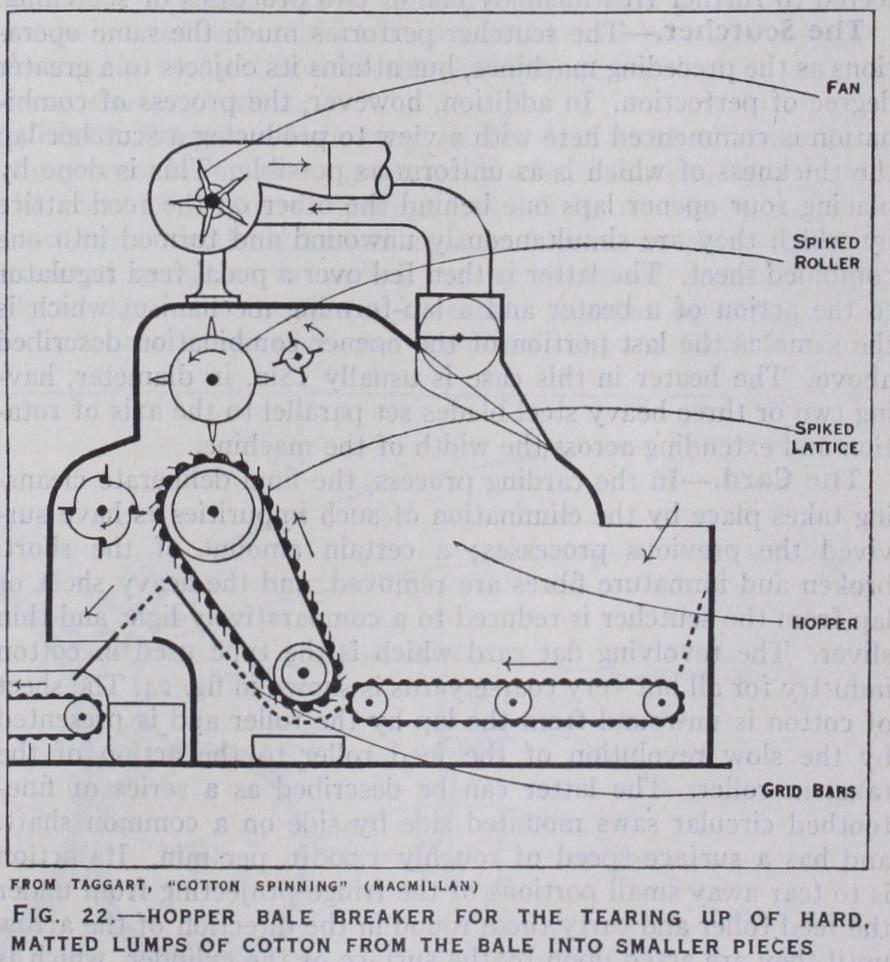

The Bale Breaker.

The bale breaker, in the great majority of cases, is of the hopper type (fig. 22). The raw material in the form of hard, compressed slabs from the bale is fed by hand into the hopper, where it is then lifted by the spiked lattice until it comes under the influence of the spiked evener roller above. The latter allows only a small portion to proceed, and throws the rest back into the hopper for further treatment ; while the dust freed by the consequent agitation of the cotton is drawn off to a dust chamber by the fan. The tearing action of the two sets of spikes thus reduces the material into a fairly fluffy state, so that in passing over the grid bars some of the loosened heavy impurities are able to fall out. The cotton is then conveyed either by lattices or by pneumatic trunks to the opener machine which follows. The roller breaker, though in some cases still in use, is now obsolete and need not be described here.Owing to its great variability, cotton from suitably chosen bales of different grades is mixed in the bale breaker in order to main tain a consistent quality of yarn, and for ordinary purposes, treat ment by the subsequent machines is relied upon to make the mix ture complete. In some cases, however, principally in mills spin ning fine yarns, mixing is assisted by building up a stack of cotton from the breaker in horizontal layers, and after leaving it for two or three days to become aerated, pulling it down in vertical layers to be fed to the opener.

The Opener.

The opener is usually in the form of a combi nation of several machines. Its functions are, broadly speaking, the same as those of the bale breaker, by which treatment the cotton is still farther opened up, freed from the greater part of its heavy impurities, and made into the form of a rolled up sheet or lap, of about the thickness of a heavy blanket, ready for the next proc ess. A typical example of a small opener combination is shown in (fig. 23). The cotton is first fed to a hopper feeder, similar to the hopper breaker already described, which serves to present it in the form of a sheet to the action of the pedal regulator motion, shown in the illustration. The latter consists of a series of levers, 2 to 21in. wide, arranged side by side across the width of the machine on a common fulcrum arm. The short arms or pedal noses are kept in contact with the feed roller by a weight hung at the end of a series of links which connect the long arms together. This arrangement of links integrates the movements of the pedals and is connected to a cone belt drive by which the speed of the feed roller can be varied. Thus, if an unusually large bulk of material is passing under the feed roller, the total amount of depression of the pedal noses is increased, and the consequent raising of the link mechanism acts through the cone drums to reduce the rate of delivery. In this way a further im provement is made in the uniformity of the sheet presented to the action of the porcupine cylinder. The latter may be some 4Iin. in diameter, and consists of a series of plates carrying steel blades revolving at about 800r.p.m. The cotton is struck upwards by the blades and carried round to be flung against the grids through which a considerable proportion of the heavier impurities are discarded. The beaten flakes of material are then withdrawn from the cylinder casing at its lower end by pneumatic suction generated by the fan, and after passing over further grids, are deposited on the wire mesh cages, through the near surfaces of which the air is exhausted. By the revolution of the cages the cotton is then delivered in a fairly uniform sheet through the rollers to the heavy calender rollers, which, after a threefold compressing action, pass it on to be rolled up into a lap.

Such a combination is only suitable for very clean cottons. In most cases it would be augmented by the inclusion of other opening units, the number and character of which would depend on the amount of impurity which has to be expelled. A revolving beater of one kind or another is the main feature of all, the varia tions being introduced in the matter of size, speed, size of beater blade and arrangement of grids. In rare cases, where the cotton used is of exceptionally high grade, the opener lap is passed straight to the carding operation, but in most cases it is sub jected to further treatment by one or two processes of scutching.

The Scutcher.

The scutcher performs much the same opera tions as the preceding machines, but attains its objects to a greater degree of perfection. In addition, however, the process of combi nation is commenced here with a view to producing a scutcher lap the thickness of which is as uniform as possible. This is done by placing four opener laps one behind the other on the feed lattice by which they are simultaneously unwound and formed into one combined sheet. The latter is then fed over a pedal feed regulator to the action of a beater and a lap-forming mechanism which is the same as the last portion of the opener combination described above. The beater in this case is usually i8in. in diameter, hav ing two or three heavy steel blades set parallel to the axis of rota tion and extending across the width of the machine.

The Card.

In the carding process, the final deliberate cleans ing takes place by the elimination of such impurities as have sur vived the previous processes; a certain amount of the short, broken and immature fibres are removed, and the heavy sheet or lap from the scutcher is reduced to a comparatively light and thin sliver. The revolving flat card which is the type used in cotton industry for all but very coarse yarns is shown in fig. 24. The sheet of cotton is unwound from the lap by the roller and is presented by the slow revolution of the feed roller to the action of the taker-in roller. The latter can be described as a series of fine toothed circular saws mounted side by side on a common shaft, and has a surface speed of roughly i,000ft. per min. Its action is to tear away small portions of the fringe projecting from under the feed roller and carry them round in the direction of the arrow until they are acted upon by the surface of the cylinder, which is uniformly covered with closely set steel wire teeth secured in a cloth and rubber foundation. (For the sake of clearness the wires are made to appear in the figure much larger and more openly spaced than is actually the case.) The cylinder has a surface speed of about 2,000ft. per min., so that the fibres are stripped from the taker-in and carried in an upward direction until they come under the influence of the flats. These are narrow iron bars which may be On. to tin. wide, covered with wire teeth similar to those on the cylinder, and moving in the same direction as the latter but at a very slow speed. The wires of the flat clothing point in the opposite direction to those of the cylinder clothing, and since they are set so that the clearance between them is only 6 to io-thousandths of an inch, the flats exercise a retarding in fluence on the material being carried round on the cylinder, and thus set up a semi-combing action. In this way part of the fibres are transferred from the cylinder to the flats, and remain there unless taken back again by the cylinder before they are with drawn from the carding surface at the front of the machine. It is generally understood that such a re-transfer does in fact take place in the case of the longer fibres, but that the short fibres and impurities remain on the flats and are eventually stripped by the comb and brush to form flat strip waste. The latter constitutes some 3% to 5% of the total amount going through, according to the grade of cotton being used.On leaving the influence of the flats, the fibres on the cylinder, now in fairly parallel order and uniformly distributed over its surface, are taken off in a continuous sheet by the doffer, which is also clothed with wire points, facing into those of the cylinder, but which has only about 1/25 the surface speed. Here, no combing of any sort takes place. In fact the reverse; inasmuch as the material is condensed, and what parallel order previously existed is destroyed. It is only in this way that the fibres are enabled to cling together; so that they can be stripped by the rapid oscillation of the doffer comb in the form of a fine transparent web, and ultimately gathered together in the form of a sliver which is coiled in the cylindrical can by the coiler mechanism. We now have a card sliver, which, although still containing a certain amount of neps, or small bunches of unripe fibres, is almost entirely free from impurities, and whose weight per yard is some ioo to i 20 times less than that of the scutcher lap. In addition to the cleaning action of the flats, a further quantity of short fibres and heavy impurities are discarded through the mote knives and the grids.

After the carding process, the treatment of the material depends on the class of yarn to be spun. For counts of 6os and upwards, and for extra quality yarns of coarser count the cotton is sub jected to a combing process whereby the shorter fibres are re moved to the extent of some i 5 % to 20% of the total weight, according to the quality desired and the cotton being used. In other cases the card sliver is passed through two, three or four passages of drawframes whose functions are to parallelize the fibres and increase the regularity of the weight per unit length of the material.

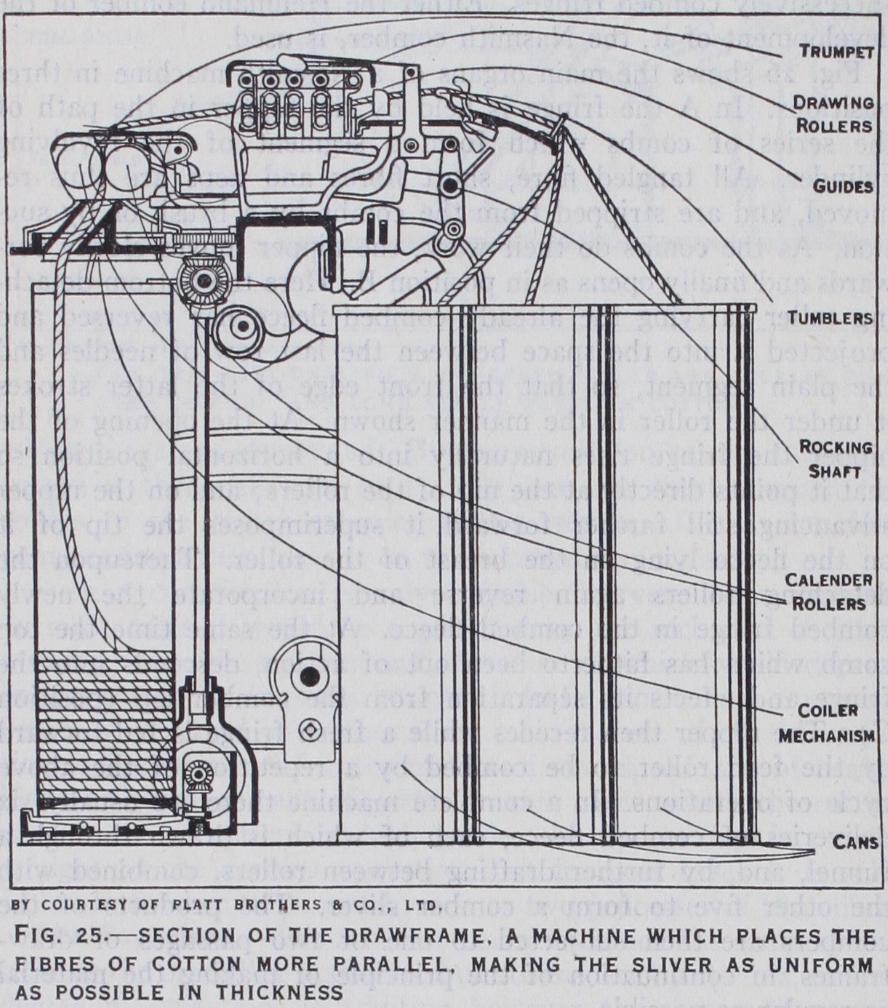

The Drawframe (fig.

25).—Four, six, or eight slivers from the cans are passed side by side over tumblers and through guides to four successive pairs of rollers which are suitably spaced and driven in such a way that the surface speed of each pair is greater than that of the preceding pair. In this way material passing from the grip of one pair to the next is stretched between them, thereby creating what is known as a draft. If the surface speed of the front pair of rollers is six times that of the back pair, there is constituted a total draft of six. The bottom rollers are of steel, longitudinally fluted, and positively driven by gear ing, while the top ones, either fluted steel or leather covered, are driven by surface contact, being loaded by heavy weights hung on their bosses. If six slivers are fed in at the back, then the draft of the machine is arranged to be six or slightly less; so that throughout the drawing process the issuing drawframe slivers are only slightly less in weight per unit length than the original car d slivers; but owing to the drawing or drafting ac tion of the rollers the fibres are gradually drawn out into parallel order, and by making one sliver out of six, the regularity of the material is greatly increased. The material as it emerges from the nip of the front rollers is in the form of a narrow sheet which is drawn by the calender rollers through the trumpet and coiled in the can by the coiler mechanism. There is one tumbler to each sliver and each is so balanced that if the sliver breaks or the can runs empty, it lifts up into the position shown by the dotted line. Its lower end thus comes into contact with the oscillating bar on the rocking shaft, and by an arrangement of levers stops the machine. In a similar way, if the issuing sheet should for any reason lap round the front roller, the trumpet, being freed from the restraining action of the material, rises and also stops the machine. The third stop motion is the full-can stop motion which is operated by the pressure of the coiled-up sliver lifting the plate. The products of the first passage of drawframes are then treated in a similar way in the second passage : and so on, until the requisite amount of regularizing and parallelizing has been accomplished.

Combing.

Cotton which has to be combed requires to be in the form of a lap which may vary from 7 tin. to i 2in. in width. Moreover, to avoid unnecessary waste, the fibres must be in paral lel formation. To obtain these conditions there are two methods of procedure. One is to pass sliver which has been processed by one head of drawframes, through a sliver lap machine. The latter, in its functions, is identical with the drawframe except that the issuing sheet of cotton is rolled straight up into a lap instead of being formed again into a sliver by being drawn through a trumpet. In addition, the sheet is thicker, since the number of slivers fed together at the back of the frame may be as many as 20. The other method is to take the sliver straight from the card through a sliver lap machine to a ribbon lap machine, where six sliver laps are separately drafted by an arrangement of drawing rollers, superimposed and rolled up ready for combing. Whichever method is adopted the final product is known as a comber lap.

The Comber.

The comber is one of the most complicated and intricate pieces of mechanism used in the spinning processes, but while the settings and speeds of the various parts have to be regulated with the greatest care, the principle of its method of treating the cotton is relatively simple. The essential parts of the machine are : a device for feeding forward a fringe of comber lap at regular intervals; an arrangement of combs which at the right time pass through the fringe ; and means for piecing up the successively combed fringes. Either the Heilmann comber or the development of it, the Nasmith comber, is used.Fig. 26 shows the main organs of a Nasmith machine in three positions. In A the fringe is held by the nipper in the path of the series of combs which form a segment of the revolving cylinder. All tangled fibre, short fibres and neps are thus re moved, and are stripped from the combs by a brush or by suc tion. As the combs do their work, the nipper moves slowly for wards and finally opens as in position B. Here the bottom detach ing roller carrying the already combed fleece has reversed and projected it into the space between the last row of needles and the plain segment, so that the front edge of the latter strokes it under the roller in the manner shown. At the opening of the nipper the fringe rises naturally into a horizontal position so that it points directly at the nip of the rollers ; and on the nipper advancing still farther forward it superimposes the tip of it on the fleece lying on the breast of the roller. Thereupon the detaching rollers again reverse and incorporate the newly combed fringe in the combed fleece. At the same time the top comb which has hitherto been out of action, descends into the fringe and effects its separation from the comber lap (position C). The nipper then recedes while a fresh fringe is fed forward by the feed roller to be combed by a repetition of the above cycle of operations. In a complete machine there are usually six deliveries of combed fleece, each of which is drawn through a funnel, and, by further drafting between rollers, combined with the other five to form a comber sliver. The products of the combers are then subjected to one or two passages of draw frames, in continuation of the principle of making the material as regular as possible.

Flyer Frames.

Following on the last head of drawframes the process becomes one principally of attenuation. To this end the material is passed through two, three or four passages of machines collectively known as flyer frames, in which again the essential operation is carried out by means of drawing rollers. Up to this point the slivers have held together by virtue of the natural cohesive properties of the fibres ; but any further attenua tion makes it necessary to insert twist in order to maintain the material in the form of a continuous length. Hence the utiliza tion of a revolving bobbin and flyer (fig. 27) which gives to these machines their names.In the first of these frames, known as the slubbing frame, cans of sliver from the last process of drawframes are arranged behind the machine. Each sliver is drawn out by means of three pairs of rollers, and as it emerges from the front pair is drawn through a hole in the top of the flyer, down the hollow leg of the latter, shown on the left of the figure, and on to the bobbin. The flyer is attached to, and driven by, the spindle at a uni form speed, and inserts the amount of twist necessary to make the strand hang together. This twist, however, must be the mini mum required for its purpose, since too much will make it impossible to continue the process of attenuation in the subse quent machines. The bobbin is loosely mounted upon, but driven independently of, the spindle, so that the difference between their respective speeds effects the winding on. This is done in closely wound spirals and in successive layers, by suitably raising and lowering the bobbin relative to the spindle. Provision is made for shortening the vertical traverse of the bobbin as each layer is laid down. Moreover, since the rate of winding would other wise be affected by the increasing diameter of the bobbin, the speed of the latter is altered by a special differential mechanism to suit the constant delivery of the front roller.

The other machines of this group, known respectively as the intermediate, roving and jack frames, differ from the slubbing frame in only three respects. First, instead of having cans of sliver put at the back, racks or creels of suitable size are provided to carry the bobbins on which the material is now wound. Sec ondly, the dimensions of all the frame parts, including bobbins and flyers, are reduced at each stage as the material becomes more and more attenuated. And thirdly, it is usual to arrange for the strands from two bobbins to be fed together to the drawing rollers and combined into one at the front, thereby assisting to maintain the uniformity of the material. The amount of attenu ation effected by these machines, and, therefore, the number of stages in which it is done, de pends on the count of yarn sub sequently to be spun. For coarse yarns, the slubbing and interme diate frames only may be used, whereas for very fine yarns the work is carried out in the four stages finishing with the jack frame. In all cases the final product of this group of machines is known generally as roving.

Spinning.—It only remains now to carry the attenuation one stage farther and to convert the drawn-out roving into a yarn by the insertion of sufficient twist to prevent any further slippage between the constituent fibres. The machine employed may be either a ring spinning frame or a mule. In the ring spinning frame (fig. 28), the proc esses of twisting and winding the yarn upon a bobbin simultane ously and continuously, as is the case with the flyer frames. Here, however, the flyer is substituted by a smooth annular ring formed with a flange at its upper edge, over which is sprung a light C shaped piece of wire known as a traveller. The spindle, to which the bobbin is firmly attached, projects vertically through the ring, and is supported on a fixed rail by a self-aligning and automati cally lubricated bearing. Rotary motion is derived from the tin roller by a band passing round the wharve, which is fixed to a sleeve on the spindle in such a way that it envelops the bolster or upper part of the bearing. High speeds can thus be obtained without causing any appreciable vibration. After passing through the rollers, the roving is twisted into a yarn which passes first through a guide-eye and then through the traveller on to the bob bin. As the latter revolves the traveller is dragged round the ring by the yarn, and so inserts the necessary twist. The speed of the traveller, however, is less than that of the bobbin, owing to the lag which is permitted by the constant delivery of roving from the front roller. In this way the bobbin, acting through the traveller, not only inserts the twist but winds the material on to itself, the deposition of the coils being determined by the vertical movement of the rail which carries the ring.

In the mule (fig. 29) the action, unlike that of the ring frame, is intermittent ; i.e., first, a certain length of roving is drawn out and twisted, and then twisting ceases and winding-on takes place. The resulting cop of yarn is built upon the bare spindle in suc cessive conical layers. At any instant during the twisting process, therefore, a portion of the already spun yarn is coiled in spiral fashion from the nose of the partly built cop to the top of the spindle : and, in order that no winding-on shall take place at the same time, the spindles are inclined slightly towards the rollers, thereby enabling the top coil to slip off at each revolution. Fol lowing the material through the machine: the roving from bob bins, mounted in the creel, is passed in the usual way through the drawing rollers and then between two faller wires to the spindle which is mounted on a carriage whose wheels run on rails called slips.

Spinning commences with the carriage close up to the rollers. As the attenuated roving is delivered by the latter the carriage moves away and the spindle, being rapidly revolved by bands passing from the tin roller, inserts the desired amount of twist into the regularly increasing stretch of material between the rollers and the spindle tip. The distance the carriage travels may be from 54in. to 66in., and is known as the draw or stretch. At the end of the stretch the mechanism driving the spindles during the outward journey is disengaged, the direction of rotation is reversed and backing-off takes place. In this operation the yarn coiled round the exposed part of the spindle is unwound and the "slack" produced by the added length of yarn is taken up by the opera tion of the faller wires. It then remains for the spindle but to reverse once more and, while the carriage moves back rapidly towards the rollers, to wind the spun thread in another layer on the cop. The upper faller wire shown in the figure is responsible for guiding the yarn in the correct manner, and is for that pur pose controlled by a special cop-shaping device. All the motions of the mule are governed automatically and are regulated to suc ceed each other in their proper order, the termination of one operation being the initiation of the next. The foregoing is but a brief outline of the functions and possibilities of the machine. In addition there are numerous devices for varying the treatment of the material whereby it is possible to spin anything, from the very coarsest to the very finest of yarns. Originally the invention of Crompton, the modern self-acting mule embodies the products of hundreds of other ingenious minds, and may be regarded as one of the most marvellous automatic machines ever devised in any industry, though Crompton's first mule was controlled manually throughout the process.

Doubling.—Where it is desired to combine two or more threads from the spinning machine in order to make the product more suited to any particular purpose, the single yarns from the cops or bobbins, as the case may be, are subjected to a process of doubling. To prepare threads for this process it may be neces sary to wind the required number side by side upon a flanged bobbin, or upon a straight or a tapering spool, before twisting them into one. Doubling machines may be either continuous or intermittent in action. In the former the twist may be inserted in fundamentally the same way as it is in the ring spinning frame ; while in the latter the machine resembles the mule in operation. No attenuation is required : hence drawing rollers are substi tuted by feed rollers. In both types the threads may be twisted in a dry condition, or may be moistened in some suitable manner so as to produce a firmer and smoother thread.

Finishing and Making-up.—Yarns which are required to have a maximum of lustre and smoothness are subjected to a process of gassing or singeing. The thread is passed several times through a bunsen flame at such a speed that the fibres projecting from the surface are burnt off without injury to the rest. Such yarns may also be polished by repeated calenderings between a pair of heavily loaded rollers.

Mule spinning and doubling does not require the yarn to be wound on to an expensive and bulky wooden bobbin as in the case of continuous spinning. The cops are therefore practically ready for transport when doffed; i.e., when withdrawn from the spindles. Ring yarn, on the other hand, has to be wound off the bobbin and put up into some form more suitable for despatching to the manufacturer. Thus it may be wound on a cardboard foundation into a self-contained conical or cylindrical package, or it may be reeled into hanks or skeins, which can be packed as a neat compressed bundle.