Cotton Spinning and Manufacture

COTTON SPINNING AND MANUFACTURE During thousands of years the spinning of yarn and the weav ing of cloth persisted as a manual operation. At the outset primi tive appliances were used which through the centuries were developed and refined until highly productive and efficient devices were evolved. Their proper employment was still dependent on the skill and manipulation of the operator and, therefore, pro duction remained comparatively small. From India and Asia the knowledge of the manipulation of cotton to produce yarn or thread spread throughout Europe. Legend has it that the Indian spinners could produce a yarn of such extreme fineness that when woven into a piece of muslin the fabric could easily be passed through a ring. Although perhaps not so fine as the legendary fabric a piece of muslin brought from India about the year 1 786 proved conclusively that the hand workers of that country could produce a yarn and fabric of exquisite fineness. Comparing the yarn with the standards of to-day the counts were 25o'. Cotton counts are estimated in the following way : if one hank or skein of cotton yarn weighs I lb. avoirdupois then the counts of the yarn are is. So that where the counts of yarn are it follows that 25o hanks of 84oyd. each hank, weigh i lb. Approximately the length of I lb. of this yarn would be 119m., which will give an idea of its extreme fineness.

It is certainly true that even if this excellence of manipulation was not passed on from India to Europe the spinners and weavers of the mediaeval ages possessed considerable ability as is evi denced by the fabrics that have been preserved from that period. Time occupied in the production of fabric must have been an important factor. Certainly the operatives worked much longer hours and were satisfied with much less return for their labour. It is well to remember that at the outset cotton clothing did not altogether find favour and the extension of its use was slow. Linen and woollen fabrics were more in demand.

Hand Appliances.

Crude forms of spinning wheels were used by the Indian spinners and most certainly the principle of construction was maintained until such wheels were deposed by power-driven mechanism. Similarly there are early examples of hand looms which in character and appearance resemble closely those that were in general use during the early part of the I Sth century. It is a curious and singular fact that although England was a late-comer in the field of cotton yarn and fabric produc tion, it was in that country that the greatest developments took place, for from the inventive brains of its citizens sprung prac tically the whole of the machines which have advanced the cotton industry to its present considerable and important position.

To appreciate fully the great and radical changes effected by the inventors of the latter half of the 18th century it is necessary to understand the machinery then existent. The spinning wheel had been improved but still remained a manually operated device. It is recorded that in 1519 Leonardo da Vinci invented a flyer which, consisting of a (l shaped device the legs of which extended on either side of the spinning spindle, facilitated the operations of twisting and winding the thread on the said spindle. Also, in 153o there is a record of Johann Jurgen making a wooden flyer. Later the Brunswick spinning wheel was invented in 1533.

From that date onwards it is conceivable that improvement fol lowed advancement in craftsmanship and knowledge until we come to the quite excellent spinning wheels of the early days of the i8th century.

Weaving Operations.

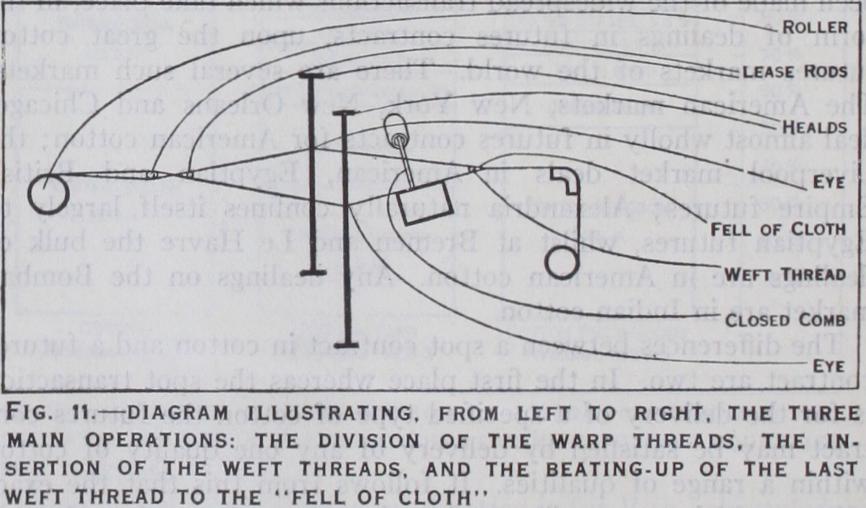

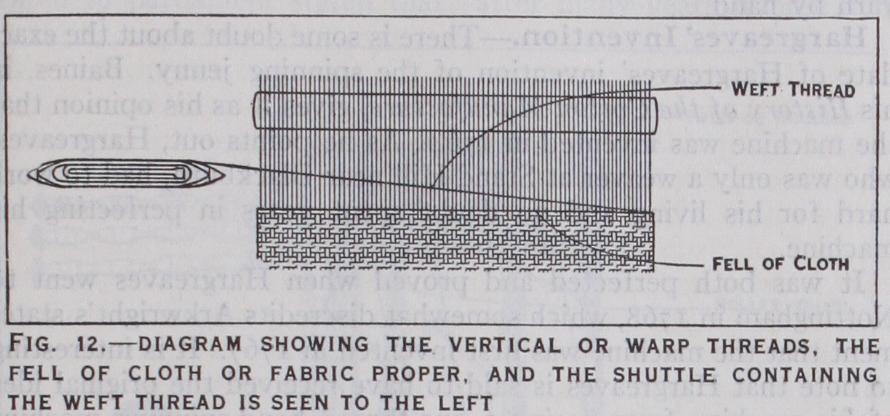

The hand loom had also been refined although in principle it remained the same as that used in the 4th and 5th centuries. Essentially there are three main operations in weaving. They are the division of the warp or horizontal threads of the fabric so that the weft or cross-threads may be interwoven or interlaced between them ; the insertion of the weft or cross-threads; and the beating-up of the last inserted weft thread to the "fell of the cloth" or the fabric proper. Simple diagrams illustrate this point (fig. 11). The warp or horizontal threads are wound on a beam or roller and are drawn forward, being divided by lease rods before they pass through the eyes of the dividing appliances or healds. Each heald frame sup ports a number of strands of yarn intermediate in the length of which is an eye through which an individual thread is drawn. By raising one heald frame and lowering the other, division of the warp threads is secured. What is termed a shed is formed, and through this opening the shuttle containing the weft or cross-thread is passed from side to side. When this has been accomplished the weft thread is forced or beaten up to the fell of the cloth by means of a closed comb, or reed suitably supported, and between the teeth of which the individual warp threads pass. There are other secondary motions in weaving such as winding up the woven cloth, but of primary motions there are but three.

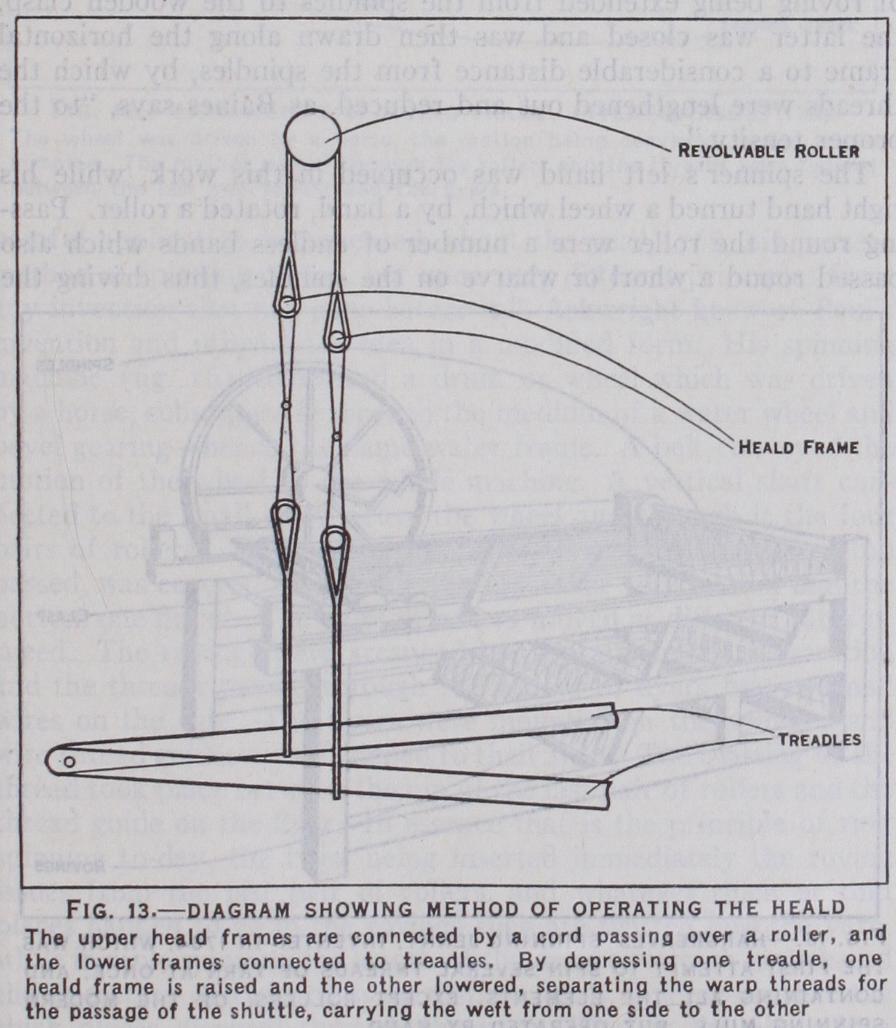

It will be readily conceived that a simple method of operating the heald is that shown in the line illustration herewith (fig. 13). The upper heald frames are connected together by a strap or cord passing over or attached to a revolvable roller. The lower heald frames are connected to treadles. By depressing one treadle, one heald frame is lowered and the other raised in order to divide the warp threads. Modifications and additions were made to hand looms in order to secure greater variety of weave than the simple plain cloth which was the original product. But up to the method of passing the shuttle carrying the weft from one side of the warp to the other by hand still obtained. It was in that year that John Kay invented his "flying" shuttle and inaugurated that great inventive epoch which before the end of the century was to revolutionize the whole of the cotton industry of England and eventually of the world.

Kay's "Fly" Shuttle.

It will be appreciated that the method of operation of "picking" described above was slow. Kay's inven tion was of extreme importance and value and will be more readily appreciated from examination of the illustration herewith (fig. 14). To the lathe, Kay added two small boxes, one on either side, the lower face of the boxes being in correct alignment with the race board or upper face of the lathe. These boxes were for the reception of the shuttle, and, in each, spindles were fixed. On each spindle a piece of wood or leather was threaded, this being known as a picker. The two pickers were connected to gether with fly cords which the weaver when at work held in his hand by a small handle, called in the old days a fly pin. It will be readily understood that a shuttle having been placed in one box, by a sharp jerk or flick of the fly pin in a direction across the loom the weaver could project the shuttle through the shed from box to box. The right hand being wholly used for the pur pose, the left hand was free to operate the lathe to beat up the weft, thus materially increasing the speed of weaving and naturally increasing production.

State of the Industry.

It is essential at this point to consider the state of the industry to fully appreciate the effect of Kay's in vention and the later developments which were so considerable. There was quite an organized industry in existence in the early part of the i8th century. In Manchester particularly there were factors or merchants who bought largely the fabrics made in cer tain villages and small townships of Lancashire. In fact, very much as it is to-day, the Manchester of those days was a trading rather than a manufacturing centre. In the villages surrounding Bolton and Rochdale the weavers had their habitation and their looms. They secured yarn from the factors or merchants, who took in return the cloth they wove and paid to them the difference. It is no doubt true that some of the weavers were independent workers and after having bought their own yarn and woven it into cloth could afford to wait for their returns until they sold the prod uct. Merchants had their own weavers working for them, although such weavers were probably not all in one village or town. Figures are available which show what wages were paid to men, women and children about 175o. The return varied, but a man on the average earned about 6s. a week. A woman averaged slightly less, about 5s. 6d. per week, while children earned an average of 2s. 6d. These were weavers. Among spinners—who were mostly women— the wages earned varied from 2s. to 5s. per week and girls from six to 1 2 years of age could earn from is. to i s. 6d. per week. The following figures give the imports of cotton "wool" (as it was then termed) into England during the early years of the i8th century : Year. lb. Year. lb.1701. I,985,868 1720. I,972,805 1710. 1730. An interesting comparison can be made here between the imports of 173o and 1927 which will demonstrate clearly the enormous development of the industry. In the former year as shown 47 2 lb. of all sorts of cotton were imported into England, in 1927 the amount was approximately 12,540,000,000 lb.

Effect of Kay's Invention.

Kay was a luckless inventor. As has been stated the weaver by using the fly shuttle could increase the production of the loom. Fearing that through this increase they would be thrown out of employment the weavers rose and attacked Kay's house, all his machines and effects being destroyed. He emigrated to France, where he eventually died. Kay's inven tion did not put the weavers out of work, but it did bring about a shortage in yarn supply. The hand spinning wheels were not able to cope with the demand made upon them, and although in 1761, 1765 and 1767 a number of inventions were introduced which were intended to improve their productive capacity, there was still a shortage of yarn for the weavers. The time was undoubtedly ripe for the production of a mechanical spinning device which would be at least semi-automatic in its action and operation.

Principles of Spinning.

To appreciate fully what was re quired from the inventor it is essential to understand the principles of cotton spinning and what is involved. From a matted mass of material—individual fibres which are lying in all directions—it is necessary, in order to produce yarn, first to arrange the fibres in parallel order, and secondly to reduce the number of fibres to the cross-section to such a degree that a comparatively fine thread may be spun. The manual operative spinner drew the fibres out by hand as the revolving spindle twisted them and then allowed the twisted thread to wind round the spindle.It is curious that the inventors who attacked the problem of finding improved methods of spinning did not at the outset concern themselves with the earlier or preparation machines, that is those which open out the matted mass of fibre, clean it and to a certain extent parallelize the fibres. Their efforts were directed to finding a machine that would give them an increased production over the best hand spinning wheels then in existence. There is evidence of considerable inventive activity throughout England from 174o-5o and undoubtedly in many directions men were busily engaged in experimental work. Considerable controversy has since arisen as to who really invented many of the mechanisms which have been embodied in cotton spinning machinery from that time. News would travel slowly owing to the inadequate transport facilities and there can be no doubt that a number of men were working along precisely similar lines.

The Early Inventors.

At this date it matters little whether Wyatt or Lewis Paul invented the method of drafting or attenuat ing by the use of rollers. The invention is credited to the latter and it was in 1738 that he took out his patent. His invention was of extreme importance because it made the subsequent machines of Hargreaves, Arkwright and Crompton possible. Lewis Paul's own words extracted from his patent specification explain his invention quite clearly : "The wooll or cotton being thus prepared, one end of the mass, rope, thread or sliver, is put betwixt a pair of rowlers cillinders or cones or some such movements, which being turned round by their motion, draws in the raw mass of wooll or cotton to be spun, in proportion to the velocity given to such rowlers, cillinders or cones; as the prepared mass passes regularly through or betwixt those rowlers, cillinders or cones a succession of other rowlers, cil linders or cones moving proportionably faster than the first, draw the rope, thread or sliver into any degree of fineness which may be required." Here we have in a few words the whole principle of drafting or attenuating the sliver or untwisted rope of fibres in order to reduce the number of such fibres in the cross-section and thus enable the spinning of a thread of comparative fineness. The invention was the first real step towards emancipation from the production of yarn by hand.

Hargreaves' Invention.

There is some doubt about the exact date of Hargreaves' invention of the spinning jenny. Baines, in his History of the Cotton Manufacture, gives it as his opinion that the machine was invented in 1764. As he points out, Hargreaves, who was only a weaver at Stand Hill near Blackburn, had to work hard for his living and no doubt spent years in perfecting his machine.It was both perfected and proved when Hargreaves went to Nottingham in i 7 68, which somewhat discredits Arkwright's state ment that the machine was first invented in i 767. It is interesting to note that Hargreaves is said to have received the original idea of his machine from seeing a one-thread hand-spinning machine overturned on the floor, when both the wheel and the spindle con tinued to revolve. The spindle was thus thrown from a horizontal to a vertical position and the thought seems to have struck him that if a number of spindles were placed upright several threads might be spun at once. The illustration herewith (fig. 15) will assist the following description. A frame was made in one part of which were placed rovings in a row, and in another part a row of spindles. The rovings, when extended to the spindles, passed be tween two horizontal bars of wood forming a clasp which opened and shut in a like manner to a parallel ruler. When pressed to gether the clasp or clamp held the threads fast. A certain portion of roving being extended from the spindles to the wooden clasp, the latter was closed and was then drawn along the horizontal frame to a considerable distance from the spindles, by which the threads were lengthened out and reduced, as Baines says, "to the proper tensity." The spinner's left hand was occupied in this work, while his right hand turned a wheel which, by a band, rotated a roller. Pass ing round the roller were a number of endless bands which also passed round a whorl or wharve on the spindles, thus driving the latter. The roving was thus spun or twisted into yarn and by return of the clasp to its original position and letting down a presser or guiding wire, the yarn was wound upon the spindle. The presser, or, as it is termed today, faller wire, is of importance. It maintained the yarn during the twisting process at the tip of the spindle. It will be appreciated that the latter, revolving rapidly, would have a tendency to wind up the material, but as the yarn is held at the tip, it constantly slips off the said tip and thus twisting takes place. In Hargreaves' machine you have practically the ele ments of the present-day mule, the operations being manually per formed and not mechanically. The machine is an intermittent drafter, twister and winder-on much as the mule is to-day. It might be observed that no rollers for drafting were employed by Hargreaves and also that rollers not only reduce the number of fibres to the cross-section, but also, owing to their differences in rate of speed, parallelize the fibres passing through them.

Arkwright's Invention.

Arkwright, in the "case" he pre sented to parliament stated that "after many years intense and painful application he invented, about the year 1768, his present method of spinning cotton, but upon very different principles from any invention that had gone before it." Arkwright knew of Paul's invention and utilized the idea in a modified form. His spinning machine (fig. 16) comprised a drum or wheel which was driven by a horse, subsequently through the medium of a water wheel and bevel gearing—hence the name water frame. A belt conveyed the motion of the wheel to the whole machine. A vertical shaft con nected to the small drum drove the wheel and through it the four pairs of rollers. The part of the roller through which the cotton passed, was covered with wood, the top roller with leather and the bottom one fluted. The pairs of rollers moved at different rates of speed. The rovings were arranged horizontally in the illustration and the threads passed through the rollers to flyers having small wires on the side. The flyers were mounted on the spindles and wire thread guides were fastened to their sides. The twisting of the thread took place between the nip of the last pair of rollers and the thread guide on the flyer. In essence that is the principle of ring spinning to-day, the twist being inserted immediately the roving issues from the last pair of rollers, and whatever thick or thin places happen to be in the rovings such are twisted into the yarn, while in mule spinning the length of the draw or°stretch is such and the operation of twisting is so distinct from winding-on that the thick places disperse through the yarn. That is the fibres in a thick place run along the other fibres and fill up the thin places.

Crompton's

"Mule."—Crompton practically combined Har greaves' and Arkwright's invention and the cross was termed a "mule." It is interesting to note how they name the frames. Owing to the fact that the flyer of Arkwright's frame gave out a whistling sound like a thrush singing it was called a "throstle frame." Later when it was operated through the medium of water power it was called a "water frame." It has been said that the word "mule" applied to Crompton's invention was not because it was a cross between Hargreaves' and Arkwright's machines but because it spun yarn fine enough to be used in the fabrication of muslin and that the original name was the "muslin" wheel afterwards corrupted into "mule." It is inferred that he commenced to make his machine in and completed it in 1779, combining principles of the two ear lier inventions. For example, Crompton took Arkwright's system of spindles without bobbins, which in combination with the faller or presser wire gave the twist to the yarn. The said yarn in this type of machine is stretched and spun at the same time as it was in Hargreaves', but the action is automatic and involves the stoppage of the rollers when a sufficient length of roving has been paid out. The most noteworthy feature of the machine invented by Cromp ton is the movable carriage which carries the spindles. The car riage was in Crompton's machine, drawn out for a distance of from S4in. to 56in. from the roller beam—this is known as the draw—in order to stretch and twist the thread. It will be remem bered Hargreaves moved his clasp out by hand, his spindles being stationary. When twisting is complete, the carriage moves back towards the roller beam, the yarn winding on to the spindles in the process.It will be recognized that within a comparatively short time from 1738 to 1779, many considerable and far-reaching improve ments had been made. The productive capacity of the spinner was multiplied many times, and, moreover, the quality of the yarn was immensely improved. It might be stated here that the alteration in movement of direction of the mule carriage had to be governed by hand. It was Roberts, in 1830, who invented the self-acting mule which removed the onus of government from the spinner and put it on the machine.

Preparatory Machines.

The cotton received in bale form is in a matted tangled condition, charged with dust, twig, broken leaf, broken seed and other foreign matter which must be removed before actual spinning can take place. The fibres must be cleaned, disentangled and arranged in parallel order to facilitate the produc tion of yarn or thread. Crude hand-operated devices were origi nally used, but with the advent of the spinning machinery it was recognized that the enormously increased production capacity of such machines necessitated revolutionary changes in the prepara tion processes. The invention of Lewis Paul rendered the produc tion of one important preparatory machine a comparatively easy matter and led also to the production of three others. The machines referred to are the "drawing" or "drafting" frame which essentially comprises successive pairs of rollers running at increased speeds, and the three subsequent machines known to-day as the "slubbing" "intermediate" and "roving" frames which embody the same idea. The object of such frames is to reduce the number of fibres to the cross-section and to parallelize them. A machine was devised to open the matted dirty cotton taken from the bale, such machine comprising a hopper or bin into which lumps of cotton were fed, and within which a roller having a number of projecting spikes was caused to revolve. The spikes came in contact with the cotton and tore it apart, while a strong air current induced by a powerful fan freed it from most of the dust and seed it contained. In Snodgrass, then resident in Glasgow, invented a further cleaning machine which remains practically the same to-day. It was termed a "scutcher" and comprised three or four metallic blades revolving on an axis at a speed of from 4,00o to 7,00o revolutions per min ute. The material to be opened was presented to the rapidly revolving blades over the edge of a metallic feed plate, and as the cotton was broken up the dust, leaf, seed and other foreign matter was beaten out and dropped through grids into a dust chamber. A further machine of similar type was employed and with it was combined a lapping machine whereby the cotton in the form of an endless sheet was rolled round a central spindle or core. From the final scutcher the "lap," as it is termed, proceeds to the carding engine. The early hand card consisted merely of brushes having short pieces of wire arranged at a certain angle. The cotton was laid upon the back of one hand card while it was combed or brushed with the teeth of another. It was a simple evolution to increase the size of the cards to make one fixed and to suspend the other by a movable cord and pulley from the ceiling thus materi ally increasing production. It was Lewis Paul in 1748 who con ceived the idea of a rotary cylinder covered with card clothing or wire teeth and a set of stationary "flats" or strips of wood fitted with card clothing placed below the cylinder. This was the genesis of our present-day card, the only difference being that the flats are now placed above the cylinder, are formed in an endless chain and travel at a slow rate of speed over the cylinder, which is running at a high rate of speed.

Machine Production.

Refinement followed refinement. The early makers of textile machinery were the spinners themselves who called in the local blacksmith to assist at the production of the comparatively crude mechanical devices then in vogue. It was, however, speedily appreciated that the demand for textile machin ery was likely to develop and that the production of such ma chinery could not be left in the hands of the spinners if such demand was to be met. As early as 1790 the first textile machin ists' shop was organized and opened in Bolton, and it was followed up to 183o by a number of others which are still in existence to-day. It is rather remarkable that the British textile machinists have practically had a monopoly in the supply of spinning machin ery for the world. In later days there has been competition in such countries as the United States, such competition being fostered by the erection of tariff-walls, but in India, the East and in every country in Europe the majority of the spindles at work have been made in Lancashire by the few but large and important firms that are engaged in machine production.

Loom Development.

We come now to the invention of the power loom by Dr. Edmund Cartwright in 1786. Cartwright mechanized the operations of weaving as previously performed by hand. His early looms were not successful, but improvements were speedily made and eventually the power loom became a commer cial and practical success. Continued use and the development of the machine industry brought about rapid and effective refinement of the loom and its development as a more accurate and precise weaving machine. It was not, however, until i800 that the power loom was a definite practical proposition, and it will be interesting at this stage to examine the industry and indicate its position in regard to spindles and looms.

Early Mill Census.

It may be fairly assumed that by the year 18i 1 the full effects of the various inventions had made themselves felt. The spinning mill by that time could be fitted with a full equipment of preparation and spinning machinery, while the weav ing shed was provided with power looms, practical and, in com parison with hand looms, highly productive. It was estimated that in 181i over 5,000,000 spindles were at work of which 310,500 were of the Arkwright—or "throstle" frame—principle, while no fewer than 4,600,000 were mule spindles of Crompton's invention and there still remained at work 156,00o spindles of Hargreaves' "jenny" type. In 182o the number of power looms at work in Eng land and Scotland was 14,500, but in 1829 the number had risen to 55,50o and in 1833 to ioo,000. Hand loom weaving had by no means died out, for in 1834 before the Commons committee on the hand loom weaver it was stated that in Scotland alone there were 45,000 to 50,000 of them at work, and it has been estimated that if such was the case, then at least 200,000 hand weavers were still at work in England.The erection of factories proceeded apace, the early examples being located near to a fall of water which for some years was the source of power supply. The early mills were distinguished by their low rooms, small window space, and generally solid look. The introduction by Watt of his steam engine was of immense importance to the spinning and weaving industry. That the new power unit was speedily taken up is reflected by the term "steam" looms—meaning no doubt looms driven by the medium of steam power—which occurs in the records about 183o. The old type of beam engine driving ponderously through heavy vertical shafts and bevel gears the machinery of the mills persisted for nearly a cen tury. It was not until about 1890 that the method of driving by ropes was introduced. By this time a slow or medium running horizontal reciprocating engine had been devised from which the shafts in the various departments of the mill were driven direct by ropes. Such method entailed a new construction of mill embody ing a rope race, but prior to this the increasing size of the various machine units of the mill had necessitated higher rooms, increased floor space and more windows of larger size. The character and appearance of the mills were materially altered.

Effect of Machines on Operatives.

An endeavour will now be made to trace the effect of machine production upon the oper atives, particularly in regard to their remuneration. In 1769, Arthur Young examined the question of wages paid for certain classes of fabrics and for yarn spun. Men weavers were in receipt of an average of 7s. 6d. per week, women 6s. per week, and children 2s. 6d. per week. Quite a variety of goods were woven, the prices naturally varying in accordance with the character and quality of the fabric. Spinners who were women and girls averaged about 3s. 6d. per week for the former and from is. to is. 6d. for the lat ter. Daniels states that in i800 the amount paid for weaving a piece of cambric which required a week for its performance was 25s. Later there was quite a decline, and by 1829 the price had fallen away to 5s. 6d. In 1835 a certain quality of cambric 24 yards long cost 6s. when woven on a hand loom and 2s. when woven on a power loom. The difference between hand loom pro duction and that of the power loom was, even in these early days, most marked, for the hand loom weaver could only produce one piece a week, while the power loom operator turned out four pieces in the same time.

Operatives Employed.

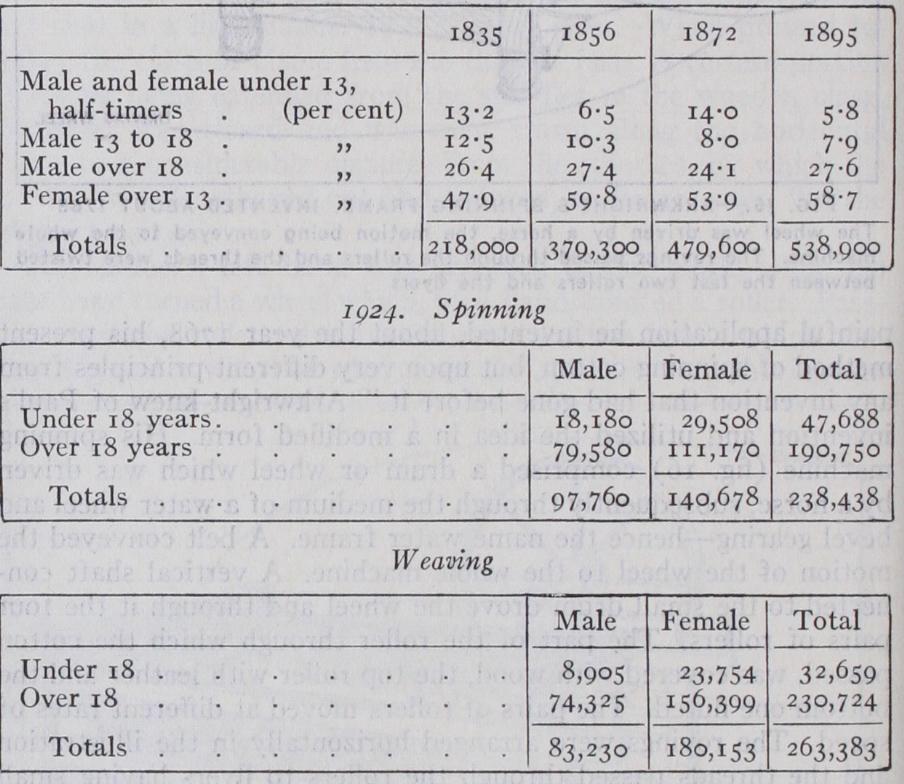

It was from 1835 onwards that we have details of the operatives employed in cotton factories in the United Kingdom, and the early figures are interesting. A com parison has been made between the years 1835, 1856, 1872, and 1924.

The figures for 1924, which were issued in March 1927, give details of employment in a somewhat different manner to the ear lier figures, and these have been separated from the table above in order to show clearly the number of employees of certain age in each broad section of the British industry.

With regard to hours, an enquiry in 1819 in reference to 325 cotton spinning mills showed that 98 worked from 721 or 731 to 82 or 93 hours a Week, while the remaining 227 ran from 66 to 72 hours a week. The pernicious system of farming out children in batches from the poorhouse was in existence, and in many cases where double shifts were in vogue, the children going off got into the same beds as those just awaking to work their turn. It was by an Act of 1844 that night work was killed because it made it illegal for any operatives who were not adult males to practise it. The large proportion of children and women essential to maintain the balance of effective operation were thus excluded and night work became commercially unremunerative. During the 19th century many acts were passed which were beneficial to the operatives. The age at which children could commence work in the factory was constantly advanced. Finally we come to the more recent act which reduced the hours in the cotton-spinning and weaving factories to 48.

Cotton mills throughout the world conform generally to an accepted form of architecture, though modifications due to locality or predilection may occur. The type of spinning mill developed between 1890 and 1900 appears as a four or five-storeyed building with an outlying or connected building of one storey, the whole structure either divided in the centre by a tower or provided at the end with one. The boiler and engine house adjoin the tower, which is designed to accommodate a rope race, the ropes in which drive the shafts of the various floors. Cotton in bale form arriving at the mill is received in a cotton warehouse, variously placed but preferably adjacent to the single-storey building which houses the machinery designed to open up the closely packed mass of raw material.

Weaving sheds are, in the main, buildings of one storey pro vided with a saw-tooth roof, glass being let into the acute angle of the tooth, which if possible faces north. The weaving shed em bodies the necessary executive offices, a yarn store, "slashing" or sizing room, the loom shed and cloth warehouse. The looms are arranged in rows with alleyways between them, and so that in each two rows they face each other, the weaver standing between her looms and being thus able to operate two or four.