Counterpoint

COUNTERPOINT, in music, the art defined by Sir Fred erick Gore Ouseley as that of "combining" melodies (Lat. con trapunctus, "point counter point," "note against note"). This neat definition is not quite complete. Classical counterpoint is the conveying of a mass of harmony by means of a combination of melodies. Thus the three melodies combined by Wagner in the Meistersinger prelude do not make classical counterpoint, for they require a mass of accompanying harmony to explain them. That accompaniment explains them perfectly and thereby proves itself to be classical counterpoint, for its virtue lies in its own good melodic lines, both where these coincide with the main melodies and where they diverge from them. From this it will be seen that current criticism is always at fault when it worries as to whether the melodies are individually audible in a good piece of counterpoint.

What is always important is the peculiar life breathed into harmony by contrapuntal organization. Both historically and aesthetically "counterpoint" and "harmony" are inextricably blended ; for nearly every harmonic fact is in its origin a phe nomenon of counterpoint. Instrumental music develops harmony in unanalyzed lumps, as painting obliterates draughtsmanship in masses of colours; but the underlying concepts of counterpoint and draughtsmanship remain.

In so far as the laws of counterpoint are derived from harmonic principles—that is to say, derived from the properties of concord and discord—their origin and development are discussed in the article HARMONY. In so far as they depend entirely on melody they are too minute and changeable to admit of general dis cussion; and in so far as they show the interaction of melodic and harmonic principles it is more convenient to discuss them under the head of harmony. All that remains, then, for the present article is the explanation of certain technical terms.

(I) Canto Fenno (i.e., plain chant) is a melody in long notes given to one voice while others accompany it with quicker counter points (the term "counterpoint" in this connection meaning ac companying melodies) . In the simplest cases the canto fermo has notes of equal length and is unbroken in flow. When it is broken up and its rhythm diversified, the gradations between counterpoint on a canto fermo and ordinary forms of polyphony, or indeed any kind of melody with an elaborate accompaniment, are infinite and insensible.

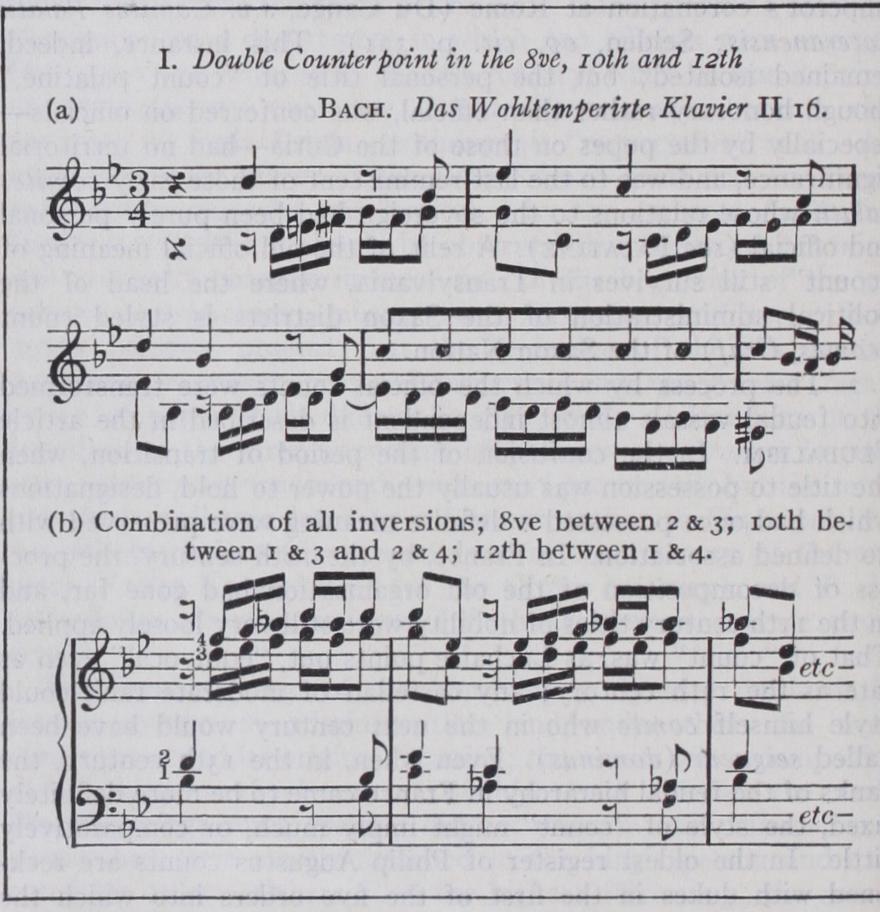

(2) Double Counterpoint is a combination of melodies so de signed that either can be taken above or below the other. When this change of position is effected by merely altering the octave of either or both melodies (with or without transposition of the whole combination to another key), the artistic value of the device is simply that of the raising of the lower melody to the surface. The harmonic scheme remains the same, except in so far as some of the chords are not in their fundamental positions, while others, not originally fundamental, have become so. But double counterpoint may be in other intervals than the octave; that is to say, while one of the parts remains stationary, the other may be transposed above or below it by some other interval, thus producing an entirely different set of harmonies.

Double Counterpoint in the 12th has thus been made a powerful means of expression and variety. The artistic value of this device depends not only on the beauty and novelty of the second scheme of harmony obtained, but also on the change of melodic expression produced by transferring one of the melodies to an other position in the scale. Two of the most striking illustrations of this effect are to be found in the last chorus of Brahms's Triumphlied and in the fourth of his variations on a theme of Haydn. Inversion in the 12th also changes the concord of the 6th into the discord of the 7th ; a property used with powerful effect by Bach in Fugue i6 of Bk. II. of Das Wohltemperirte Clavier.

Double Counterpoint in the loth

has the property that the inverted melody can be given in the new and in the original positions simultaneously.Double counterpoint in other intervals than the octave, loth and 12th, is rare, but the general principle and motives for it remain the same under all conditions. The two subjects of the "Confiteor" in Bach's B minor Mass are in double counterpoint in the octave, I I th and I 3th. And Beethoven's Mass in D is full of pieces of double counterpoint in the inversions of which a few notes are displaced so as to produce momentary double counterpoint in unusual intervals, obviously with the intention of varying the harmony.

(3) Triple, Quadruple and Multiple Counterpoint.—When more than two melodies are designed so as to combine in interchange able positions, it becomes increasingly difficult to avoid chords and progressions of which some inversions are incorrect. Triple counterpoint is normally possible only at the octave ; for it will be found that if three parts are designed to invert in some other interval this will involve two of them inverting in a third in terval which will give rise to incalculable difficulty. This makes the fourth of Brahms's variations on a theme of Haydn appear almost miraculous. The whole variation beautifully illustrates the melodic expression of inversion at the 12th; and during eight bars of the second section a third contrapuntal voice appears, which is afterwards inverted in the I2th, with natural and smooth effect. But this involves the inversion of two of the counter points with each other in the almost impracticable double counter point in the gth. Brahms probably did not figure this out at all but profited by the luck which goes with genius.

Quadruple Counterpoint is not rare with Bach ; and the melod ically invertible combination intended by him in the unfinished fugue at the end of "Die Kunst der Fuge" requires one of its themes to invert in the I2th as against the others. (See D. F. Tovey's edition published by the Oxford University Press.) Quintuple Counterpoint is admirably illustrated in the finale of Mozart's "Jupiter symphony," in which everything in the suc cessive statement and gradual development of the five themes conspires to give the utmost effect to their combination in the coda. Of course Mozart has not room for more than five of the 120 possible combinations, and from these he, like all the great contrapuntists, selects such as bring fresh themes into the outside parts, which are the most clearly audible.

Sextuple Counterpoint may be found in Bach's great double chorus, "Nun ist das Heil," in the finale of his concerto for three claviers in C, and probably in other places.

(4) Added Thirds and Sixths.—This is merely the full working out of the sole purpose of double counterpoint in the loth, namely, the possibility of performing it in its original and inverted posi tions simultaneously. The "Pleni sunt coeli" of Bach's "B minor Mass" is written in this kind of transformation of double into quadruple counterpoint; and the artistic value of the device is perhaps never so magnificently realized as in the place, at bar 84, where the trumpet doubles the bass three octaves and a third above while the alto and second tenor have the counter subjects in close thirds in the middle.

Almost all other contrapuntal devices are derived from the principle of the canon and are discussed in the article CONTRA PUNTAL FORMS.

As a training in musical grammar and style, the rhythms of i 6th-century polyphony were early codified into "the five species of counterpoint" (with various other species now forgotten) and practised by students of composition. The exercise should not claim to teach rhythm, but it does teach measurement.

The classical treatise on which Haydn and Beethoven were trained was Fux's Gradus ad Parnassum (1725). This was superseded in the Igth century by Cherubini's, the first of a long series of attempts to bring up to date as a dead language what should be studied in its original and living form. R. 0. Morris has thoroughly exposed the humbug and illustrated the true severe scholarship in The Technique of Counterpoint (Oxford University Press). (D. F. T.)