Courtship of Animals

COURTSHIP OF ANIMALS. When we see a peacock spreading his beautiful train to the full, and, occasionally vibrat ing the quills to produce a rustling sound, turning from side to side before his mate, or a barn-door cock with drooped wing and special call circling close round a hen, we are witnessing familiar examples of animal courtship.

Courtship may be defined to include all forms of action exe cuted by members of one sex to stimulate members of the other sex to sexual activity. Such actions include the display of bright colours, or adornments such as crests; special tactile contacts; dances or other antics; pursuit; music, vocal or instrumental; the discharge of scents and perfumes ; and the presentation of prey or of inedible but otherwise stimulating objects.

It is unfortunate that "courtship" is the only term available to denote these activities, since in our own species courtship is usually taken to mean only such as occur before marriage. in other words those which conduce to the finding of a more or less permanent mate. In most animals, however, marriage (in the sense of the living together of one or more males with one or more females in sexual association for considerable periods of time) does not exist, and in many birds "courtship" displays do not begin until of ter the selection of mates has taken place. Courtship, in the biological sense, primarily leads up to the act of pairing; where some form of marriage exists, courtship may also, or even primarily, be connected with the choice of mates.

By no means all organisms show even the most primitive form of courtship. It is not present in plants, or in any of the lower groups of animals. A few instances of rudimentary courtship occur in annelid worms, but otherwise it is confined to the verte brates, the molluscs, and the Arthropods. Even here it is absent from many of the lower sub-divisions of these groups. This be comes intelligible when the function of courtship is more closely looked into. No organism without a nervous system and sense organs can be expected to show courtship. In other forms, the union of the sexual cells is either entirely a matter of chance; or of simultaneous ripening and discharge (as when all sea-urchins over a wide area discharge eggs and sperm at one time) ; or of passive transference, as in flower pollination ; or of purely re flex reactions. Courtship will only be needed where the active co-operation of the sexes is needed for fertilization to be effected; and this will only be the case where the eggs and sperms are not blindly discharged, but are economized, either by means of in ternal fertilization or by being discharged in close proximity. Further, courtship will not be required where the nervous organi zation is so simple that pairing is a simple reflex action ; but only when the reflex machinery of pairing is under the control of higher centres in the brain, and the nerve-processes of these centres and their emotional accompaniments need to be stimulated in a particular way before pairing can occur.

Courtship of Invertebrates.

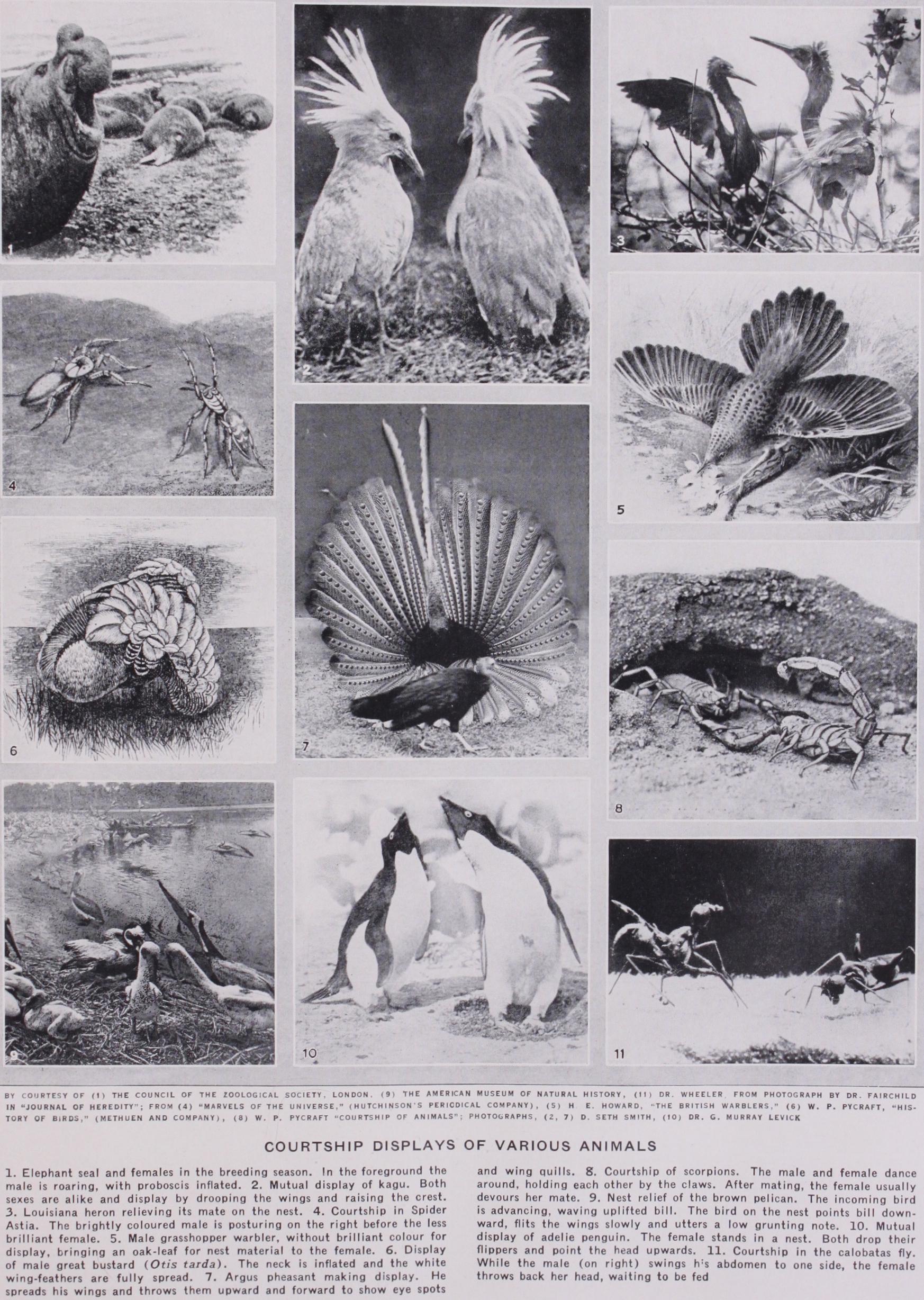

The most primitive type of action which can be called courtship is found in certain marine annelids (bristle-worms) related to the common sandworm Nereis. At the breeding season these gather together and the males indulge in extraordinary contortions. These actions, whether by sight, touch, or smell, appear to stimulate the fe males to shed their eggs, upon which the males discharge their sperm. Certain land snails are among the few molluscs which show courtship ; and this in spite of the fact that they are her maphrodite. They possess a structure called the dart, or spiculum amoris, secreted by a special sac. This is discharged with some violence during the preliminaries of mating, and appears to stimu late the other animal, whose skin it may pierce. It might be expected that the highly organized Cephalopods (q.v.) would have a striking courtship, but in spite of their peculiar method of fertilization, the meagre reports available do not bear this out. Although almost all Crustacea have well-developed special sense-organs and internal fertilization, pursuit and forcible capture is usually the only preliminary to mating. In the semi-terrestrial fiddler crabs, however, the males have one enormously enlarged claw, often brilliantly coloured, and this is employed—not as at first surmised, in fights between rival males, or forcibly carrying off females, but in a primitive form of courtship. In the breed ing season, if a mature female passes near a sexually eager male, he stands on tiptoe and brandishes his claw in the air. As Pearse says, "the males appear to be proclaiming their maleness." The fiddler crab reacts to three main types of situation—feeding, danger, and reproduction. The brandishing of the male's claw is to the female the visible symbol of the reproductive situation.A similar proclamation of a "sexual situation" appears also to be the main function of the courtship of male spiders. This, in certain of the hunting spiders (e.g., Lycosidae, Attidae), which possess good vision, consists in dances or contortions in which brightly coloured parts are prominently displayed. Web-spinning spiders, however, have poor vision; accordingly in some of them the courting male vibrates a strand of the web in a peculiar way. The importance to the males and to the race of inducing a sexual reaction in the female is here very great, since the female's nor mal reaction to any small animal would be to attack and devour it. The female does actually sometimes attempt to seize the male as prey, but gradually desists as the courtship proceeds. The male in spiders is occasionally devoured after fertilization. This appears to be the rule in scorpions, in which courtship takes the form of a dance with inter-locked claws.

Insects.

In insects, courtship is not infrequent. In many flies (e.g., Drosophila, q.v.) the male vibrates his wings in a special way. Some male butterflies, including the Blues (Lycaen idae) have scent-scales on their wings. The most remarkable of scent-producing courtships is that of Hepialus. Here the last pair of legs are transformed into or gans rather like a powder-puff, normally kept inserted in a pair of pouches lined with scent-pro ducing glands. In courtship the "powder-puffs" are used to throw scent towards the female. The sound-producing organs of grass hoppers and crickets (interesting because they probably produced the first not merely accidental and functionless sounds in the history of life) serve mainly to bring the sexes together ; but they doubtless also help to generate a sexual situation. The male of the tree-cricket Oecanthus has a unique structure on his back, consisting of a gland capable of secreting a sweet liquid; during courtship he offers this secretion to the female.Special food of a protein nature is needed by many female insects if their eggs are to undergo their final ripening. Accord ingly we find that a number of male insects present animal prey to the females as a part of courtship. In this way, two birds are killed with one biological stone. In some species of little flies of the family Enapidae, the proffered prey is embedded in a "balloon" of glistening bubbles secreted by the male, and usually larger than himself, which renders him and his gift very conspicuous. In other species a strange modification of this habit has taken place. The balloon is still made and carried, but in place of the prey, bright objects such as flower-petals are placed in it, and the flies will avail themselves of coloured paper if this is provided. This utilization of foreign objects in courtship is only paralleled elsewhere by the bower-birds and man.

Courtship of Vertebrates.

In vertebrates, no courtship ap pears to exist in Cyclostomes, nor in the majority of fishes. Defi nite courtship, with striking adornments displayed by the males, is only found in a few fish species with internal fertilization or with peculiar breeding habits. In the Cyprinodonts fertilization is internal; and here the males are often brightly coloured and armed with special prolongations of ventral fin or tail; e.g., in the sword tail (Xiphophorus) the handsome breeding males swim excitedly round the females, occasionally giving them a dig with their long tail.In the sticklebacks there are violent combats between males for the possession of nesting territory, but it is not certain whether display of the bright colours assumed by breeding males has any sexually stimulating effect on the females.

In amphibia the most specialized group (frogs and toads) have no display-courtship, since the males' habit of embracing the females and waiting thus until the eggs are shed, when they dis charge their sperm, renders it unnecessary. However, the meet ing of the sexes is facilitated by the croaking of the males, which is often very loud owing to the development of huge vocal sacs. Here again possibly, though by no means certainly, the croaking has also a sexually stimulating function. If the chirping of male grasshopper-like insects was the first deliberate sound produced by life, the croaking of male frog-like amphibia was almost cer tainly life's first vocal music. In the Urodeles, or tailed amphibia, fertilization is internal, and here courtship is not infrequent. It usually consists in the male's rubbing himself against the female, at the same time discharging the secretion of special scent-glands.

It reaches its highest pitch in the European newts—Molge (Tri ton) and related genera—where the breeding males are usually brightly coloured, and dance round the females in striking postures while fanning scent from special glands upon them with their tails. The sexually stimulating function of this performance is here very definite. The males of these genera deposit their sperm in a packet or spermatophore, and this must be actually picked up by the female for fertilization to occur. It has been shown that females are quite irresponsive to the presence of isolated sper matophores, but will pick them up when stimulated by the male's performance.

0f reptilian courtship comparatively little is known; its study, especially in the more active lizards and snakes, would be certain to yield many interesting facts.

Mammals.

The two remaining vertebrate classes, birds and mammals, differ considerably in regard to courtship, its frequency and intensity being much greater among birds, whereas its com plete or almost complete absence, not infrequently associated with male combat, is commoner in mammals. The biological rea sons for this appear to be the following: First, most female mammals, owing to their special method of nourishing their embryonic young, have their reproductive activity very strictly controlled by means of hormones. At certain definite periods the uterus is ready for the embryo's implantation and one or more ova are shed from the ovary ; simultaneously, the sexual instincts are strongly stimulated, and the female will readily mate with almost any male, at the same time becoming an object of the males' strong sexual desire owing to an odour specially produced at this period. In other words, the sexual attractiveness of the female and still more her readiness to mate are in the main chemically controlled, the intensity of sexual emotion during the period of "heat" or oestrus being in general very high. In birds, on the other hand, although the sex hormones produced in the breeding female predispose her to sexual emotion, their activity is neither so limited in time nor so intense, while in addition the males are more helpless than in most groups to enforce their desires on an unwilling female. (See REPRODUCTION, PHYSI OLOGY OF.) In most mammals, the cyclical production of female sex hor mones thus automatically ensures mating. As a result, both defi nite courtship and secondary sexual adornments are rare. Since female preference counts for so little, the winning of females by battle will secure them as mates, and consequently size and strength, as of the elephant seal, offensive weapons like stags' antlers or stallions' canines, and defensive weapons like the lion's mane or the baboon's "cape" of long hair are the chief secondary male characters.In monkeys and apes there appears the tendency, which reaches its climax in civilized man, of emancipating the female's sexual emotions from the strict cyclical control of hormones, and allow ing them free play at other times than at oestrus. The mating season is extended over more of the year, and the animals be come ready to pair at other periods of the menstrual cycle than oestrus. In such circumstances it would be expected that stimu lation by courtship and display would once more become of biological importance, and in point of fact primates do show a number of striking sexual adornments, such as beards, mous taches, or whiskers ; bright coloured hair on the face ; or brilliant ly coloured patches of bare skin on the face and buttocks. De tailed studies of simian courtship would be of great interest. In man, of course, courtship is highly developed, and obviously plays an important biological role; but it cannot be discussed in a purely zoological article.

The Courtship of Birds.

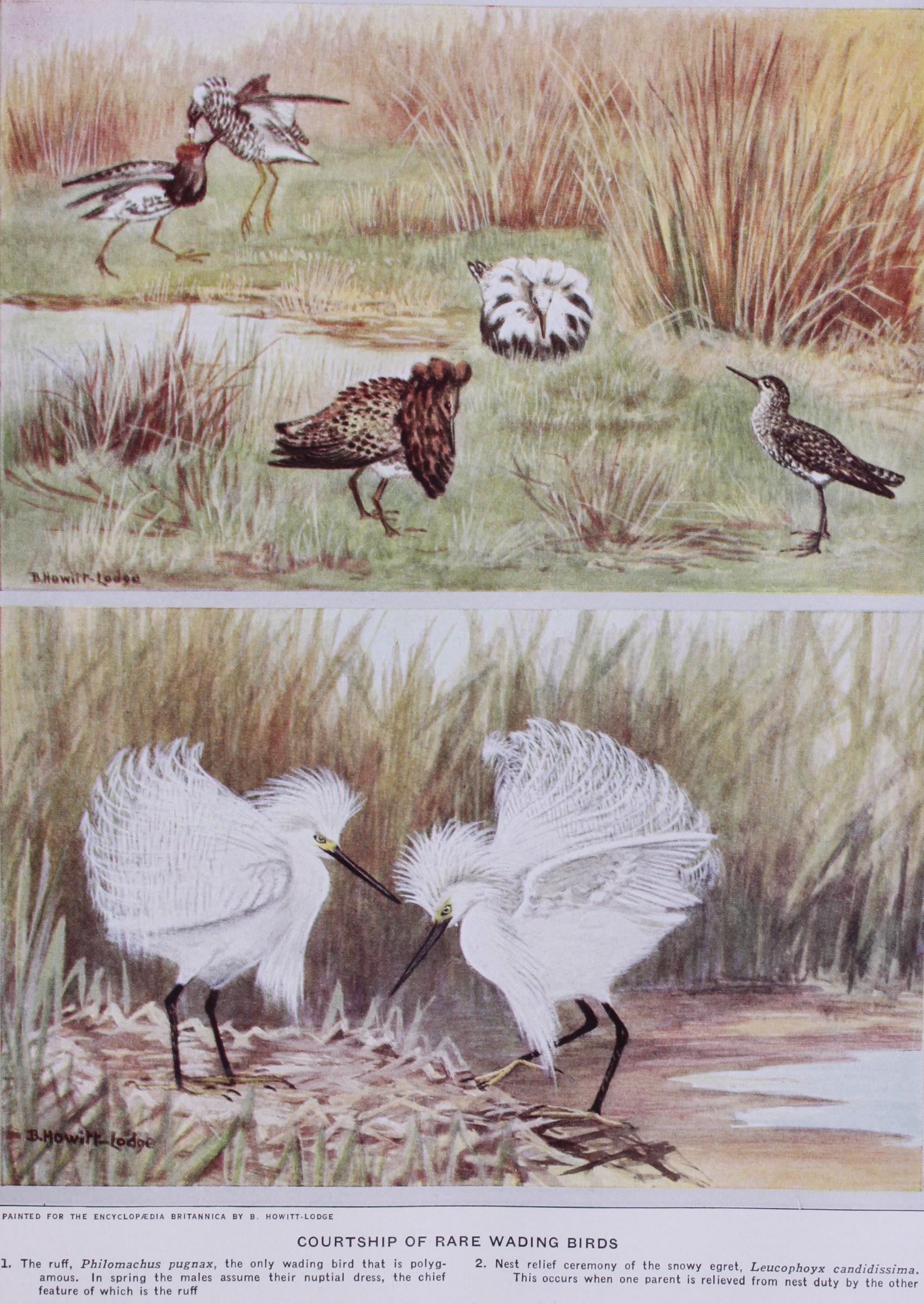

It is in birds that courtship is most universal and striking, and its details and its biological sig nificance have been here most thoroughly investigated. Conse quently, we can lay down certain general rules as regards the form which courtship takes in birds of different modes of life and reproduction.(I) The racial function of the male bird may be confined to fertilization (ruff, black grouse) ; or he may also mount guard during the female's incubation (most ducks) ; or may also share in feeding the young (most passerines and hawks) ; or also in incubation (grebes, herons, etc.) The more duties he executes for the good of the offspring, the greater is what may be called his racial value. To kill a male ruff immediately after fertili zation has no deleterious effects on the next generation, whereas the death of a male grebe or heron at the same period seriously imperils the chances of the eggs and young.

(2) The "marriage systems" of birds vary from permanent monogamy (parrots, ravens), through monogamy for one season (most monogamous birds) or one brood (some wrens), to polyg amy of the "small harem" type (jungle fowl, many pheasants), or of the promiscuous type (ruff, blackcock, probably some birds of paradise).

(3) The need for protection by means of protective coloration and inconspicuous habits varies considerably. Birds which nest gregariously in general need less protection at the nest-site than do birds nesting solitarily.

(4) The need for a continuous supply of food to the naked young of most passerine birds has resulted in the adoption by species of the system of "food-territory" in which the male and later the pair defend from intruders an area of some extent round their nest. (See